Constans

| Constans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62nd Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

Bust of Constans | |||||

| Reign | 337–350, jointly with Constantine II (until 340) and Constantius II | ||||

| Predecessor | Constantine I | ||||

| Successor | Constantius II | ||||

| Born | c. 323 | ||||

| Died |

February 350 Vicus Helena, southwestern Gaul | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Constantinian | ||||

| Father | Constantine I | ||||

| Mother | Fausta | ||||

Constans (Latin: Flavius Iulius Constans Augustus;[1] c. 323[1][2] – 350) or Constans I was Roman Emperor from 337 to 350. He defeated his brother Constantine II in 340, but anger in the army over his personal life and preference for his barbarian bodyguards led the general Magnentius to rebel, resulting in the assassination of Constans in 350.

Career

Constans was the third and youngest son of Constantine the Great and Fausta, his father's second wife.[3] He was educated at the court of his father at Constantinople under the tutelage of the poet Aemilius Magnus Arborius.[1]

On 25 December 333, Constantine I elevated Constans to the rank of Caesar at Constantinople.[1] Constans became engaged to Olympias, the daughter of the Praetorian Prefect Ablabius, but the marriage never came to pass.[3] With Constantine’s death in 337, Constans and his two brothers, Constantine II and Constantius II, divided the Roman world between themselves[4] and disposed of virtually all relatives who could possibly have a claim to the throne.[5] The army proclaimed them Augusti on September 9, 337.[1] Almost immediately, Constans was required to deal with a Sarmatian invasion in late 337, over whom he won a resounding victory.[3]

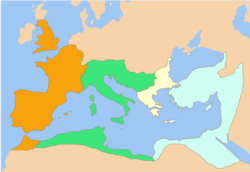

Constans was initially under the guardianship of Constantine II. The original settlement assigned Constans the praetorian prefectures of Italy and Africa.[6] Constans was unhappy with this division, so the brothers met at Viminacium in 338 to revise the boundaries.[6] Constans managed to extract the prefecture of Illyricum and the diocese of Thrace,[6] provinces that were originally to be ruled by his cousin Dalmatius, as per Constantine I’s proposed division after his death.[5] Constantine II soon complained that he had not received the amount of territory that was his due as the eldest son.[7]

Annoyed that Constans had received Thrace and Macedonia after the death of Dalmatius, Constantine demanded that Constans hand over the African provinces, which he agreed to do in order to maintain a fragile peace.[7][8] Soon, however, they began quarreling over which parts of the African provinces belonged to Carthage, and thus Constantine, and which belonged to Italy, and therefore Constans.[9] This led to growing tensions between the two brothers, which were only heightened by Constans finally coming of age and Constantine refusing to give up his guardianship. In 340 Constantine II invaded Italy.[8] Constans, at that time in Dacia, detached and sent a select and disciplined body of his Illyrian troops, stating that he would follow them in person with the remainder of his forces.[7] Constantine was eventually trapped at Aquileia, where he died, leaving Constans to inherit all of his brother’s former territories – Hispania, Britannia and Gaul.[4]

| A Nummus of Constans | |

|---|---|

_obverse.jpg) _reverse.jpg) | |

| Obverse showing Constans portrait | Reverse showing Constans on a galley |

Constans began his reign in an energetic fashion.[4] In 341-42, he led a successful campaign against the Franks, and in the early months of 343 he visited Britain.[3] The source for this visit, Julius Firmicus Maternus, does not provide a reason, but the quick movement and the danger involved in crossing the channel in the dangerous winter months suggests it was in response to a military emergency, possibly to repel the Picts and Scots.[3]

Regarding religion, Constans was tolerant of Judaism and promulgated an edict banning pagan sacrifices in 341.[3] He suppressed Donatism in Africa and supported Nicene orthodoxy against Arianism, which was championed by his brother Constantius. Although Constans called the Council of Sardica in 343 to settle the conflict,[10] it was a complete failure,[11] and by 346 the two emperors were on the point of open warfare over the dispute.[12] The conflict was only resolved by an interim agreement which allowed each emperor to support their preferred clergy within their own spheres of influence.[12]

The Roman historian Eutropius says Constans "indulged in great vices," in reference to his homosexuality, and Aurelius Victor stated that Constans had a reputation for scandalous behaviour with "handsome barbarian hostages."[3][12] Nevertheless, Constans did sponsor a decree alongside Constantius II that ruled that marriage based on "unnatural" sex should be punished meticulously. However, Boswell believed the decree outlawed homosexual marriages only.[13] It may also be that Constans was not expressing his own feeling when promulgating the legislation but was rather trying to placate public outrage at his own perceived indecencies.

Death

In the final years of his reign, Constans developed a reputation for cruelty and misrule.[14] Dominated by favourites and openly preferring his select bodyguard, he lost the support of the legions.[7] In 350, the general Magnentius declared himself emperor at Augustodunum with the support of the troops on the Rhine frontier and, later, the western provinces of the Empire.[15] Constans was enjoying himself nearby when he was notified of the elevation of Magnentius.[7] Lacking any support beyond his immediate household,[7] he was forced to flee for his life. As he was trying to reach Hispania, supporters of Magnentius cornered him in a fortification in Helena (now Elne) in the eastern Pyrenees of southwestern Gaul,[16] where he was killed after seeking sanctuary in a temple.[12] A prophecy at his birth had said Constans would die in the arms of his grandmother. His place of death happens to have been named after Helena, mother of Constantine and his own grandmother, thus realizing the prophecy.[17]

See also

Sources

Primary sources

- Zosimus, Historia Nova, Book 2 Historia Nova

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab urbe condita

Secondary sources

- DiMaio, Michael; Frakes, Robert, Constans I (337–350 A.D.), in De Imperatoribus Romanis (D.I.R.), An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

- Jones, A.H.M., Martindale, J.R. The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I: AD260-395, Cambridge University Press, 1971

- Canduci, Alexander (2010), Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors, Pier 9, ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8

- Gibbon. Edward Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire (1888)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jones, p. 220

- ↑ Victor, 41:23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DiMaio, Constans I (337–350 A.D.)

- 1 2 3 Eutropius, 10:9

- 1 2 Victor, 41:20

- 1 2 3 Canduci, pg. 130

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gibbon, Ch. 18

- 1 2 Victor, 41:21

- ↑ Zosimus, 2:41-42

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 20.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, 1930, Patrick J. Healy, Sardica

- 1 2 3 4 Canduci, pg. 131

- ↑ Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexualit, 1980

- ↑ Zosimus, 2:42

- ↑ Eutropius, 10:9:4

- ↑ Victor, 41:21:23

- ↑ Cárdenas, Fabricio (2014). 66 petites histoires du Pays Catalan [66 Little Stories of Catalan Country] (in French). Perpignan: Ultima Necat. ISBN 978-2-36771-006-8. OCLC 893847466.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constans. |

| Constans Born: 320 Died: 350 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Constantine I |

Roman Emperor 337–350 Served alongside: Constantius II and Constantine II |

Succeeded by Vetranio and Magnentius (usurper) |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Ursus , Polemius |

Consul of the Roman Empire 339 with Constantius II |

Succeeded by Septimius Acindynus, Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus |

| Preceded by Petronius Probinus , Antonius Marcellinus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 342 with Constantius II |

Succeeded by Marcus Maecius Memmius Furius Baburius Caecilianus Placidus, Flavius Romulus |

| Preceded by Amantius , Marcus Nummius Albinus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 346 with Constantius II |

Succeeded by Vulcacius Rufinus, Flavius Eusebius |