Coronations in Africa

- Note: this article is one of a set, describing coronations around the world.

- For general information related to all coronations, please see the umbrella article Coronation.

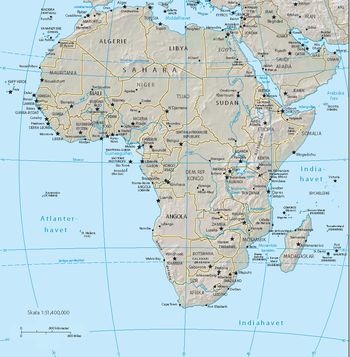

Coronations in Africa are held, or have been held, in or amongst the following countries, regions and peoples:

By country, region or people

Ashanti

The Asantehene, the ruler of the Ashanti of Ghana begins his reign by being raised and lowered over the Golden Stool (sika 'dwa), which is believed to embody the very soul of the Ashanti people, without touching it. The Golden Stool is the most sacred ritual object in Ashanti culture and only the Asantehene is allowed to touch it.

Central African Empire

The Central African Empire was a short-lived monarchical regime established in 1976 in what was then the Central African Republic, by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the nation's president. Inspired by Napoleon's coronation in 1804, "Bokassa I" staged his own elaborate ritual inside a large outdoor stadium in Bangui, his capital, on 4 December 1977. While guests sweltered in the 100-degree heat, the self-proclaimed emperor ascended a giant golden throne shaped like an eagle with outstretched wings, donned a 32-pound coronation robe containing 785,000 pearls and 1,220,000 crystal beads, and then crowned himself with a gold crown topped by a 138-carat diamond that cost over $2,000,000 to manufacture. His empress, Catherine—the youngest of his three wives—was then invested with a smaller diadem. The total bill for Bokassa's regalia alone came to $5,000,000.[1][N 1]

240 tons of food and drink were flown into Bangui for Bokassa's coronation banquet, including a tureen of caviar so large that two chefs had to carry it, and a seven-layer cake. Sixty new Mercedes-Benz limousines were airlifted into the capital, at a hefty cost of $300,000 for airfreight alone. All in all, the entire ceremony cost $20,000,000 to stage, an astronomical sum in a nation whose annual gross domestic product was only $250,000,000. The newly crowned Emperor used French aid grants to cover a significant portion of the bill, saying: "Everything here was financed by the French government. We ask the French for money, get it and waste it".[1]

In 1979, Bokassa was overthrown in a coup, carried out with French military support, by the very man he had overthrown in 1965, David Dacko.[2] The monarchy was abolished, the emperor was exiled, and his empire reverted to its former name.

Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt (1922–53) held an enthronement rite for its last ruling king, Farouk I. A controversy arose as to whether the ritual should be religious in nature, an option favored by the king, or whether it should be purely secular, which was desired by Farouk's Prime Minister at the time, Mustafa El-Nahhas. The religious ceremony envisaged the new king taking special vows in an Islamic ritual, followed by his receipt of the sword of Muhammad Ali Pasha. However, El-Nahhas insisted upon Farouk simply taking a constitutional oath before parliament, followed by a formal reception at his palace. The Prince Regent proposed combining the two ideas, but the government refused.[3]

The ceremony, which took place on 29 July 1937, followed the Prime Minister's directives. The Egyptian army swore loyalty to the new monarch, who then entered the Parliament chamber where he first greeted his mother, then listened to two speeches given by the Prime Minister and the speaker of the Upper House.[N 2] Following this, the king took his constitutional oath, and was acclaimed by the assembled legislators and guests.[3]

Farouk was overthrown in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. His son, Fuad II, was deposed in 1953 while still an infant, and the monarchy abolished.[4] Egypt is now a republic.[5]

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian Empire used a coronation ritual for its Emperors. The last such event was held on 2 November 1930, for Emperor Haile Selassie, the final monarch of Ethiopia.

Heavily influenced by Ethiopia's Coptic Christian tradition, preparation for the coronation ceremony commenced seven days prior to the actual event. Following an ancient Ethiopian custom, forty-nine Coptic bishops and priests continually chanted from the Psalter in groups of seven, in seven corners of the Cathedral of St. George, in Addis Ababa, where the crowning was to take place. On the eve of the ceremony, the imperial robes and regalia were taken into the church to be blessed and prayed over by the Abuna, or Archbishop, followed by the new Emperor and his family, who arrived at midnight and remained inside the cathedral that night in prayer.[N 3]

The following morning, the Emperor was met inside the cathedral by the Archbishop, who presented him with a Gospel book and asked him to take a four-part coronation oath. This oath required him to defend the Ethiopian Orthodox Faith, rule according to law and the interest of his subjects, safeguard the realm and establish schools for teaching of both secular and Orthodox religious subjects. After this, the Abuna read a special prayer of blessing, while drums and harps accompanied the chanting of Psalm 48. Various items of the Imperial Regalia were brought forward, blessed and presented to the new sovereign one-by-one. These items included a golden sword, a scepter of ivory and gold, the orb, a diamond-encrusted ring, two traditional lances filigreed in gold, the imperial vestments, and finally the crown. Each item was accompanied by an anointing with seven differently-scented oils. After this, the new monarch and his consort were taken on a tour of the church, then escorted outside by a procession of notables carrying palm branches and chanting: "Blessed be the King of Israel".[N 3]

Ethiopian tradition required the Emperor's consort to be crowned at the palace, three days after the coronation. However, Haile Selassie broke with this precedent, and had his wife crowned (but not anointed) in the cathedral with him. Selassie was overthrown by a military coup in 1974, and the monarchy was abolished in 1975.

Lesotho

The tiny African kingdom of Lesotho crowns its monarchs. The last such ritual was held on 31 October 1997, when current king Letsie III was crowned in a sports stadium in the capital city of Maseru. King Letsie entered the stadium escorted by units of mounted police clad in red uniforms and carrying sabers and lances. Donning a traditional coat of animal skins, the new ruler was crowned by two chieftains with a beaded headband containing a brown and white feather. Traditional dances and songs followed.[6]

Senegambia & Mauritania

The Serer people of Senegambia (Senegal and Gambia) and Mauritania crown their kings based on the tenets of Serer religion. Succession for kingship begins from the moment a prince is born. The parents must lodge their application to the Great Council of Nobles, headed by the Jaraff (the person responsible for electing the king from the royal family). The sacred ceremony is presided over by the Jaraff. After the coronation, the Maad a Sinig or Maad Saloum makes a royal proclamation, crowns his own mother or sister as Lingeer, then appoints his government.[7]

Swaziland

Swaziland, a small independent kingdom in southern Africa, held a coronation ritual in April 1986 for its current monarch, Mswati III. Although Swazi tradition required the king to wait until his twenty-first year to be crowned, Mswati was crowned three years early due to disputes between different factions in the regency council.[8] Swazi chiefs paid a tribute of 105 cattle to the family of Mswati's mother, Ntombi, as a dowry for the woman who was to become the new "Mother of the Nation". The rite itself included various secret rituals, after which the new king took part in several ritual dances in full feathered regalia. At the coronation, tribal singers repeated his imposing chain of official titles, which include "the Bull", "Guardian of the Sacred Shields", "the Inexplicable" and "the Great Mountain". The dances were described by William Smith of Time as "exhausting".[9]

Toro Kingdom

The Toro Kingdom—located in modern Uganda—crowned its current ruler, Rukidi IV, on 12 September 1995. Rukidi was the world's youngest monarch at the time, being only three years old. The boy was awakened at 2AM, then led to the palace where the rites would take place. At the entrance, Rukidi and his entourage engaged in a mock battle with a "rebel" prince, then entered to the accompaniment of the Omujaguza, the traditional Toro war-drum.[10]

Once inside, Rukidi was led to the regalia room, where the Omusuga, or head of royal rituals, called upon the gods to strike the boy dead if he was not of royal blood. Once the Omusuga was satisfied as to the new king's lineage, Rukidi was permitted to ring the royal bell, then he sounded the Nyalebe or sacred drum, following which he was blessed with blood from a slaughtered bull and a white hen. As morning broke, women (who had been barred from the ritual up to this time) were admitted to the palace. The king was seated upon the lap of a virgin girl, and was fed with a royal meal of millet dough. A coronation oath was administered with the boy lying on his side, in accordance with Toro tradition.[10]

At 10AM, the king, wearing a jewel-studded crown, was led to St. John's Anglican Cathedral where he was crowned by Anglican Bishop Eustance Kamanyire. Rukidi was given a Bible by the local Roman Catholic prelate, then returned to his palace where he was presented with a centuries-old copper spear and leather shield. Following this the king led a procession of Toro notables to inspect the royal corral, then concluded his coronation by greeting his subjects from a traditional shed.[10]

Yorubaland (Benin, Nigeria & Togo)

Relative rank amongst the dynastic paramount chieftains of the Yoruba people of Benin, Nigeria and Togo is determined by the answering of three questions: Is a chief a direct descendant of the medieval emperor Oduduwa, is he entitled to wear a ceremonial crown, and how long has said crown been in his family? If a chieftain's earliest pioneering ancestor left the emperor's kingdom of Ile-Ife with the crown that is now used to crown him in his own kingdom during his coronation ceremony, and if he claims direct descent from Oduduwa himself, then he is traditionally viewed by the Yoruba as a king of the highest possible rank (with him being surpassed in such a case by only the pre-eminent Yoruba monarchs, such as the Ooni of contemporary Ile-Ife and the Alaafin of Oyo).

Pre-coronation rites that are common amongst the Yoruba include an election to the office of king by the nobles of the realm, confirmation of said election by the Ifa oracle, going into the Iledi ritual confinement (during which a would be king learns the various traditions of his people) and swearing to a series of oaths tied to the kingship. Only after all of the foregoing has occurred is the king installed according to local custom (In Egbaland, for example, the crown is placed upon the king's head by a chieftess known as the Mooye, who is subsequently regarded as his ritual mother because she did so).

See also

- Coronation of Haile Selassie. Slideshow video from coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.

- Coronation of Bokassa I. Video from the coronation of self-proclaimed Emperor Bokassa I of the Central African Empire.

Notes

This section contains expansions on the main text of the article, as well as links provided for context that may not meet Wikipedia standards for reliable sources, due largely to being self-published.

- ↑ Several photos of Bokassa's coronation may be seen at Central African Empire: Emperor Bokassa. From theroyalforums.com website. Retrieved on 5 September 2008.

- ↑ A photo of King Farouk taken during this ceremony can be seen at "What European papers said Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine."; Al Ahram Weekly Website

- 1 2 Background information on the coronation may be found at the rastaites.com website, Coronation of HIM Haile Selassie I. Retrieved on 24 August 2008.

References

- 1 2 "Mounting a Golden Throne". Time Inc. 1977-12-19. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "French Fiddling". Time. 1979-10-08. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- 1 2 "Crowning moment". Al-Ahram Weekly. 2005-07-28. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ↑ "Egypt". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Egypt". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ↑ "Lesotho's King Letsie III crowned again". Cnn.com. October 31, 1997. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ (French) Sarr, Alioune, "Histoire du Sine-Saloum", Introduction, bibliographie et Notes par Charles Becker, BIFAN, Tome 46, Serie B, n° 3-4, 1986–1987, pp 28-30

- ↑ Mswati III. Encarta.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ↑ William E. Smith; Peter Hawthorne (September 7, 1987). "Swaziland In the Kingdom of "Fire Eyes"". Time.com. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- 1 2 3 The Boy King Archived July 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. From the safariweb.com website. Contains photos from the ceremony. Retrieved on 8 September 2008.