Cosmic neutrino background

| Part of a series on | |||

| Physical cosmology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

Early universe

|

|||

|

Components · Structure |

|||

| |||

The cosmic neutrino background (CNB, CνB) is the universe's background particle radiation composed of neutrinos. They are sometimes known as relic neutrinos.

Like the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB), the CνB is a relic of the big bang; while the CMB dates from when the universe was 379,000 years old, the CνB decoupled from matter when the universe was one second old. It is estimated that today, the CνB has a temperature of roughly 1.95 K. Since low-energy neutrinos interact only very weakly with matter, they are notoriously difficult to detect, and the CνB might never be observed directly. There is, however, compelling indirect evidence for its existence.

Derivation of the CνB temperature

Given the temperature of the CMB, the temperature of the CνB can be estimated. Before neutrinos decoupled from the rest of matter, the universe primarily consisted of neutrinos, electrons, positrons, and photons, all in thermal equilibrium with each other. Once the temperature dropped to approximately 2.5 MeV, the neutrinos decoupled from the rest of matter. Despite this decoupling, neutrinos and photons remained at the same temperature as the universe expanded. However, when the temperature dropped below the mass of the electron, most electrons and positrons annihilated, transferring their heat and entropy to photons, and thus increasing the temperature of the photons. So the ratio of the temperature of the photons before and after the electron-positron annihilation is the same as the ratio of the temperature of the neutrinos and the photons today. To find this ratio, we assume that the entropy of the universe was approximately conserved by the electron-positron annihilation. Then using

- ,

where σ is the entropy, g is the effective degrees of freedom and T is the temperature, we find that

- ,

where T0 denotes the temperature before the electron-positron annihilation and T1 denotes after. The factor g0 is determined by the particle species:

- 2 for photons, since they are massless bosons[1]

- 2×(7/8) each for electrons and positrons, since they are fermions.[1]

g1 is just 2 for photons. So

- .

Given the current value of Tγ = 2.725 K,[2] it follows that Tν ≈ 1.95 K.

The above discussion is valid for massless neutrinos, which are always relativistic. For neutrinos with a non-zero rest mass, the description in terms of a temperature is no longer appropriate after they become non-relativistic; i.e., when their thermal energy 3/2 kTν falls below the rest mass energy mνc2. Instead, in this case one should rather track their energy density, which remains well-defined.

Indirect mathematical evidence for the CνB

Relativistic neutrinos contribute to the radiation energy density of the universe ρR, typically parameterized in terms of the effective number of neutrino species Nν:

where z denotes the redshift. The first term in the square brackets is due to the CMB, the second comes from the CνB. The Standard Model with its three neutrino species predicts a value of Nν ≃ 3.046,[3] including a small correction caused by a non-thermal distortion of the spectra during e+-e−-annihilation. The radiation density had a major impact on various physical processes in the early universe, leaving potentially detectable imprints on measurable quantities, thus allowing us to infer the value of Nν from observations.

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

Due to its effect on the expansion rate of the universe during Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN), the theoretical expectations for the primordial abundances of light elements depend on Nν. Astrophysical measurements of the primordial 4

He

and 2

D

abundances lead to a value of Nν = 3.14+0.70

−0.65 at 68% c.l.,[4] in very good agreement with the Standard Model expectation.

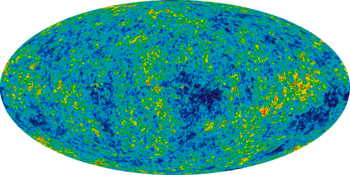

CMB anisotropies and structure formation

The presence of the CνB affects the evolution of CMB anisotropies as well as the growth of matter perturbations in two ways: due to its contribution to the radiation density of the universe (which determines for instance the time of matter-radiation equality), and due to the neutrinos' anisotropic stress which dampens the acoustic oscillations of the spectra. Additionally, free-streaming massive neutrinos suppress the growth of structure on small scales. The WMAP spacecraft's five-year data combined with type Ia supernova data and information about the baryon acoustic oscillation scale yield Nν = 4.34+0.88

−0.86 at 68% c.l.,[5] providing an independent confirmation of the BBN constraints. In the near future, probes such as the Planck spacecraft will likely improve present errors on Nν by an order of magnitude.[6]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Steven Weinberg (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-19-852682-7.

- ↑ Fixsen, Dale; Mather, John (2002). "The Spectral Results of the Far-Infrared Absolute Spectrophotometer Instrument on COBE". Astrophysical Journal. 581 (2): 817–822. Bibcode:2002ApJ...581..817F. doi:10.1086/344402.

- ↑ Mangano, Gianpiero; et al. (2005). "Relic neutrino decoupling including flavor oscillations". Nucl.Phys.B. 729 (1–2): 221–234. arXiv:hep-ph/0506164

. Bibcode:2005NuPhB.729..221M. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2005.09.041.

. Bibcode:2005NuPhB.729..221M. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2005.09.041. - ↑ Cyburt, Richard; et al. (2005). "New BBN limits on physics beyond the standard model from He-4". Astropart. Phys. 23 (3): 313–323. arXiv:astro-ph/0408033

. Bibcode:2005APh....23..313C. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2005.01.005.

. Bibcode:2005APh....23..313C. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2005.01.005. - ↑ Komatsu, Eiichiro; et al. (2010). "Seven-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Cosmological Interpretation". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 192 (2): 18. arXiv:1001.4538

. Bibcode:2011ApJS..192...18K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/2/18.

. Bibcode:2011ApJS..192...18K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/2/18. - ↑ Bashinsky, Sergej; Seljak, Uroš (2004). "Neutrino perturbations in CMB anisotropy and matter clustering". Phys. Rev. D. 69 (8): 083002. arXiv:astro-ph/0310198

. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69h3002B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.083002.

. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69h3002B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.083002.