Cynthia Ann Parker

| Cynthia Ann Parker | |

|---|---|

Cynthia Ann Parker and her daughter, Topʉsana (Prairie Flower), in 1861 | |

| Native name | Naduah (Narua) |

| Born |

c. 1825[1][2][3] Crawford County, Illinois |

| Disappeared |

May 19, 1836[1][2] Fort Parker, Texas |

| Status | Recaptured during the Battle of Pease River on December 18, 1860 |

| Died |

March 1871[4] Anderson County, Texas |

| Cause of death | Influenza |

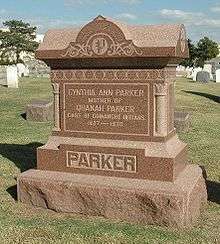

| Resting place |

Fort Sill Post Cemetery 34°40′10″N 98°23′43″W / 34.669466°N 98.395341°W |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Peta Nocona |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Silas M. Parker and Lucy Duty |

| Relatives | Daniel Parker, John Richard Parker |

Cynthia Ann Parker, or Naduah (Comanche Narua)[5] (c. 1825 – March 1871)[1][2] was an American of European descent who was kidnapped in 1836, at the age of about ten (possibly as young as 8 or already over 11 – her birth year is uncertain), by a Comanche war band, who had massacred her family's settlement. Her Comanche name means "someone found." She was adopted by the Comanche and lived with them for 24 years, completely forgetting her American ways. She married a Comanche chieftain, Peta Nocona, and had three children with him, including the last free Comanche chief, Quanah Parker. At approximately age 34, she was finally recaptured by the Texas Rangers, but spent the remaining ten years of her life refusing to adjust to life in white society. At least once, she escaped and tried to return to her Comanche family and children, but was again brought back to Texas. She found it difficult to understand her iconic status to the nation, which saw her as having been redeemed from the Comanches. Heartbroken over the loss of her family, she stopped eating and died of influenza in 1871.

Early life

Cynthia was born to Silas M. Parker and Lucy Parker (née Duty) in Crawford County, Illinois. Her birth date is uncertain; according to the 1870 census of Anderson County, Texas, she was born in 1824 or 1825.[1] Her middle name is also uncertain. Originally, it was Ana, but over the years, her name was changed to Ann. When she was nine or ten years old, her grandfather, John Parker, was recruited to settle his family in north-central Texas; he was to establish a settlement fortified against Comanche raids, which had been devastating to the Euro-American colonization of Texas and northern Mexico. The Parker family, its extended kin, and surrounding families established fortified blockhouses and a central citadel—later called Fort Parker—on the headwaters of the Navasota River in what is now Limestone County.

Fort Parker massacre

John Parker, the patriarch of the family, had experience in negotiating with various Indian nations going back to the 18th century, when he was a noted ranger, scout, Indian fighter, and soldier for the United States. Consequently, when he negotiated treaties with the local non-Comanche Indians, he and higher authorities thought that those treaties would result in the local Indians being allies with the Comanche. The Comanche, however, did not recognize treaties signed by other Indian nations, and had such a fearsome reputation that no other Indians would dare oppose them.

On May 19, 1836, a force of anywhere from 100 to 600 Indian warriors[6] composed of Comanches accompanied by Kiowa and Kichai allies, attacked the community. John Parker and his men, who lacked sufficient knowledge of the Comanches' military prowess, were caught in the open and unprepared for the ferocity and speed of the Indian warriors. They managed to fight a rearguard action to protect some of the escaping women and children, but soon all of the settlers retreated into the fort. The Indians attacked the fort and quickly overpowered the outnumbered defenders. They took John, Cynthia, and some others alive. Cynthia watched as the other women were raped and the men tortured and killed. The last victim was John. He was castrated, his genitals stuffed into his mouth, scalped, and, at last, killed. Cynthia and five captives, after watching the horror, were led away into Comanche territory. Texans quickly mounted a rescue force. During the Texans' pursuit of the Indians, one of the captives, a young teenage girl, escaped. All of the other captives were released over a period of years as ransom was paid, but Cynthia remained with the Indians for nearly twenty-five years.[7] She may have been as young as 8, or just older than 11, when she was captured.

Cynthia Ann Parker and Peta Nocona

Cynthia was soon integrated into the tribe. She was given to a Tenowish Comanche couple, who adopted her and raised her as their own daughter. She forgot her original ways and became Comanche in every sense. She married Peta Nocona, a chieftain. They enjoyed a happy marriage, and as a tribute to his great affection to her, he never took another wife, although it was traditional for chieftains to have several wives. They had three children, famed Comanche chief, Quanah,[8] another son named Pecos (Pecan), and a daughter named Topʉsana (Prairie Flower).

Capture by Texas Rangers at Pease River

In December 1860, after years of searching at the behest of Cynthia's father and various scouts, Texas Rangers led by Lawrence Sullivan Ross discovered a band of Comanche, deep in the heart of Comancheria, that was rumored to hold American captives. In a surprise raid, the small band of Rangers attacked a group of Comanches in the Battle of Pease River.

After limited fighting, the Comanches realized they were losing and attempted to flee. Ranger Ross and several of his men pursued the man whom they had seen giving orders. The chief was fleeing alongside a woman rider. As Ross and his men neared, she held a child over her head. The men did not shoot, but instead surrounded and stopped her. Ross continued to follow the chief, eventually shooting him three times. Although he fell off his horse, he was still alive and refused to surrender. Ross's cook, Antonio Martinez, who had been taken captive and tortured in Mexico after Nocona killed his family, identified him as Nocona. With Ross's permission, Martinez killed Nocona.[9]

The Rangers began questioning the woman fleeing with Nocona and other surviving Comanches for signs that she was Cynthia. When Ross arrived back at the campground, he discovered that she had blue eyes. He assured her that no young boys had been killed in the battle, so her sons, Quanah and Pecos, were safe.[10] At last, clutching her two-year-old daughter, Topʉsana, in broken English she identified herself and her family name.[11] Her information matched what Ross knew of the 1836 Fort Parker Massacre.[12]

There is some question whether the man killed was actually Nocona. Cynthia stated that he was her personal servant, a Mexican slave named José Nakoni.[13] Her granddaughter, Nelda Parker Birdsong, said, "Out of respect to the family of General Ross, do not deny that he killed Peta Nakoni. If it is any credit to him to have killed my father, let his people continue to believe that he did so."[13]

Realizing Cynthia had forgotten most of her English and would be unhappy if separated from the life she knew, some Rangers urged Ross to let her return to the Comanches, but he felt it best to try to return her to her birth family. He sent her and her child to Camp Cooper. He then notified her uncle, Colonel Isaac Parker.[14][15] When Colonel Parker mentioned that his niece's name was Cynthia, she slapped her chest and said, "Me Cincee Ann."[12] He took her to his home near Birdville.[16]

Cynthia's return to her birth family captured the country's imagination. Tens of thousands of Texan families, and many more throughout the U.S., had suffered the loss of family members, especially children, in Indian raids. She was the granddaughter of a famous American patriot, a Marylander who had met a violent end in far-off Texas. This gained her special attention and gave hope to those who had lost relatives to the Comanche. In 1861, the Texas legislature granted her a league (about 4,400 acres) of land and an annual pension of $100 for the next five years,[17] and made her cousins, Isaac Duke Parker and Benjamin F. Parker, her legal guardians.[18]

Cynthia never adjusted to her new surroundings, and although white and physically integrated into the community, she was uncomfortable with the attention she got. Her brother, Silas Jr., was appointed her guardian in 1862, and took her to his home in Van Zandt County. When he entered the Confederate Army, she went to live with her sister, Orlena Parker O'Quinn.[19] According to some, the cause of her unhappiness was that she missed her sons and worried about them.[17] Writing in the Crowell Index on October 8, 1909, Tom Champion opined, "I am convinced that the white people did more harm by keeping her away from them than the Indians did by taking her at first."[20]

Death

In 1864, Cynthia's daughter, Topʉsana, caught influenza and died of pneumonia. Losing the only child she had had contact with since her return to her birth relatives caused her to be stricken with grief. She began refusing food and water and resisted encouragement to save herself. She died in March 1871 at the O'Quinn home and was buried in Foster Cemetery on County Road 478 in Anderson County near Poyner.[3][notes 1]

There is some confusion about Cynthia's actual birth and death dates. Different sources place her birth from 1825 to 1827 in Coles, Clark, or Crawford counties of Illinois, and her death from 1864 to 1871 in Anderson County.[21] The only record of her death, given as March 1871, is found in the unpublished notebook of Susan Parker St. John.[21] The only known document from the period supports the March 1871 date; An 1870 census for Anderson County lists her as a member of the O'Quinn household, born "abt 1825," age forty-five.[3]

In 1910, Cynthia's son, Quanah, moved her body to Post Oak Mission Cemetery near Cache, Oklahoma.[22][notes 2] When he died in February 1911, he was buried next to her. Their bodies were moved in 1957 to the Fort Sill Post Cemetery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[17][notes 3]

Aftermath

The city of Crowell, Texas, has held a Cynthia Ann Parker Festival to honor her memory. The town of Groesbeck, holds an annual Christmas Festival at the site of old Fort Parker every December. It has been rebuilt on the original site to exact specifications. Over time, Cynthia's story has been told from multiple historical and cultural perspectives. One of the most recent long-form explorations is Texas Tech University history professor emeritus Paul H. Carlson's 2012 book, Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker.

An elementary school in Houston, is named for Cynthia.[23]

Fictional and dramatic representations

- Cynthia Parker (c. 1939) is a one-act opera composed by Julia Smith.

- The 1954 novel The Searchers, by Alan Le May, is loosely based on Cynthia's life story.

- The 1956 movie The Searchers was based on Le May's novel, directed by John Ford, and featured John Wayne as an obsessed frontiersman searching for years for his kidnapped niece.[24][25] Natalie Wood and her younger sister, Lana Wood, portray the kidnapped woman at different ages.

- In the 1957 book The Hanging Tree, a collection of short stories by Western writer Dorothy M. Johnson, the story "Lost Sister" is a fictionalized account of Cynthia's recapture and her difficulty reintegrating into the white world.

- The 1979 graphic novel Comanche Moon by Jaxon depicts Cynthia's story from her adoption by the Comanches through the life and death of her son, Quanah.

- Ride the Wind (1982) by Lucia St. Clair Robson is a fictionalized account of Cynthia's capture and life among the Comanches.

- Season of Yellow Leaf (1983) by Douglas C. Jones is a fictionalized story of Cynthia's life.

- Gone the Dreams and Dancing (1984), also by Jones, is a fictionalized story of Cynthia's son, Quanah, after he surrendered at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and "walked the white man's road."

- The character "Stands With A Fist" in the 1990 movie Dances With Wolves is based on Cynthia.[26]

- Where the Broken Heart Still Beats (1992) by Carolyn Meyer is a fictionalized account of Cynthia's return to her birth family.

- The Dutch writer Arthur Japin wrote a book, De overgave (2007), about the life of the Parker family and the loss of Cynthia.

Notes

- ↑ Foster Cemetery, Anderson County, Texas; First Gravesite of Cynthia Ann Parker: approximately 6 miles north of Brushy Creek off FM 315 on Millnar Road in Foster Cemetery: Texas marker #8793 32°02′32″N 95°35′57″W / 32.042272°N 95.599084°W

- ↑ Post Oak Mission Cemetery, Comanche County, Oklahoma 34°37′23″N 98°45′35″W / 34.62310°N 98.75970°W

- ↑ Fort Sill Post Cemetery 34°40′10″N 98°23′43″W / 34.669466°N 98.395341°W

References

- 1 2 3 4 Schmidt Hacker, Margaret: Cynthia Ann Parker from the Handbook of Texas Online (November 3, 2011). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Find a grave: Cynthia Ann Parker".

- 1 2 3 Frankel 2013, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Frankel 2013, pp. 19–20, citing Parker St. John, Susan, Notebook, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

- ↑ Taa Nʉmʉ Tekwapʉ?ha Tʉboopʉ (Our Comanche Dictionary). 2010 revision. Elgin, Oklahoma: Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee.

- ↑ Gwynne 2010.

- ↑ Richardson, Rupert Norval (1933), The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement: A Century and a Half of Savage Resistance to the Advancing White Frontier, Arthur H. Clark Co., OCLC 2472637

- ↑ Hosmer, Brian C.: Quanah Parker from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 15, 2010). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Benner 1983, p. 54.

- ↑ Benner 1983, p. 56.

- ↑ Pease River from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 15, 2010). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Benner 1983, p. 57.

- 1 2 Muncrief, Dennis (January 2004). "The Story of Cynthia Ann Parker". Rootsweb. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ Davis, Charles G.: Camp Cooper, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online (February 5, 2011). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Selden, Jack K., Jr.: Isaac Parker from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 15, 2010). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Hart, Brian: Birdville, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 12, 2010). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Michno, Gregory; Michno, Susan (2007), A Fate Worse Than Death: Indian Captivities in the West, 1830–1885, Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press, pp. 35–39

- ↑ Hesler, Samuel B.: Parker, Benjamin F. from the Handbook of Texas Online (June 15, 2010). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ "United States Census, 1870," database with images, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MXGV-SBB : accessed 2 June 2016), Cynthia Parker in household of Jas R Ophimo, Texas, United States; citing p. 212, family 1521, NARA microfilm publication M593 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 553,072.

- ↑ Exley 2001, p. 176.

- 1 2 Frankel 2013, pp. 86.

- ↑ "Post Oak Mission", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society, archived from the original on 2011-11-03

- ↑ "School Information / Overview". Houston Independent School District.

- ↑ Hoberman, J. (February 22, 2013). "American Obsession: 'The Searchers,' by Glenn Frankel". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ↑ McBride 2001, p. 552.

- ↑ Aleiss, Angela (2005). Making the White Man's Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies. p. 145.

Sources

- Benner, Judith Ann (1983), Sul Ross, Soldier, Statesman, Educator, College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 9780890961421

- Exley, Jo Ella Powell (2001), Frontier Blood: Saga of the Parker Family, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-1-58544-136-5

- Frankel, Glenn (2013), The Searchers: The Making of An American Legend, New York: Bloomsbury

- Gwynne, S. C. (2010), Empire of the Summer Moon, ISBN 978-1-4165-9105-4

- McBride, Joseph (2001), Searching for John Ford: A Life, New York: St. Martin's Press

Further reading

- Brown, John Henry (1880), "Account of the 1836 attack Parker's Fort", Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, The Portal to Texas History

- Carlson, Paul H. (2012), Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker, ISBN 978-0896727465

- Cynthia Parker program notes

- Hacker, Margaret (1990), Cynthia Ann Parker: The Life and the Legend, Texas Western Press, ISBN 978-0-87404-187-3

- Meyer, Carolyn (1992), Where the Broken Heart Still Beats: The Story of Cynthia Ann Parker, Gulliver Books, ISBN 978-0-15-295602-8

- Robson, Lucia St. Clair (1985), Ride the Wind, Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-345-32522-8

- Selden, Jack (2006), RETURN: The Parker Story, ISBN 0-9659898-2-8