Darkness

Darkness, the polar opposite to brightness, is understood to be the condition of a very small amount or even an absence of visible light.

Humans are unable to distinguish color in conditions of either high brightness or darkness.[1] In conditions of insufficient light, perception is achromatic and ultimately, black.

The emotional response to darkness has generated metaphorical usages of the term in many cultures.

Complete darkness is when the sun is more than 18 degrees below the horizon.

Scientific

Perception

The perception of darkness differs from the mere absence of light due to the effects of after images on perception. In perceiving, the eye is active, and the part of the retina that is unstimulated produces a complementary afterimage.[2]

Physics

In terms of physics, an object is said to be dark when it absorbs photons, causing it to appear dim compared to other objects. For example, matte black paint does not reflect much visible light and appears dark, whereas white paint reflects lots of light and appears bright.[3] For more information see color. An object may appear dark, but it may be bright at a frequency that humans cannot perceive.

A dark area has limited light sources, making things hard to see. Exposure to alternating light and darkness (night and day) has caused several evolutionary adaptations to darkness. When a vertebrate, like a human, enters a dark area, its pupils dilate, allowing more light to enter the eye and improving night vision. Also, the light detecting cells in the human eye (rods and cones) will regenerate more unbleached rhodopsin when adapting to darkness.

One scientific measure of darkness is the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale, which indicates the night sky's and stars' brightness at a particular location, and the observability of celestial objects at that location. (See also: Sky brightness)

Technical

The color of a point, on a standard 24-bit computer display, is defined by three RGB (red, green, blue) values, each ranging from 0-255. When the red, green, and blue components of a pixel are fully illuminated (255,255,255), the pixel appears white; when all three components are unilluminated (0,0,0), the pixel appears black.

Cultural

Artistic

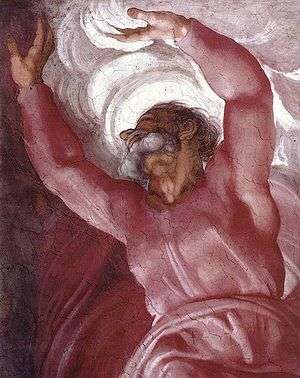

.jpg)

Artists use darkness to emphasize and contrast the presence of light. Darkness can be used as a counterpoint to areas of lightness to create leading lines and voids. Such shapes draw the eye around areas of the painting. Shadows add depth and perspective to a painting. See chiaroscuro for a discussion of the uses of such contrasts in visual media.

Color paints are mixed together to create darkness, because each color absorbs certain frequencies of light. Theoretically, mixing together the three primary colors, or the three secondary colors, will absorb all visible light and create black. In practice it is difficult to prevent the mixture from taking on a brown tint.

Literature

As a poetic term in the Western world, darkness is used to connote the presence of shadows, evil, and foreboding. The 1820 short story "A Visit to the Lunar Sphere" tells of a darkness machine where prisms reflect light into bottles where it is captured.[4]

Religion

The first creation narrative in Christianity begins with darkness, into which is introduced the creation of light, and the separation of this light from the darkness (as distinct from the creation of the sun and moon on the fourth day of creation). Thus, although both light and darkness are included in the comprehensive works of the almighty God—darkness was considered "the second to last plague" (Exodus 10:21), and the location of "weeping and gnashing of teeth." (Matthew 8:12)

The Qur'an has been interpreted to say that those who transgress the bounds of what is right are doomed to "burning despair and ice-cold darkness." (Nab 78.25)[5]

Philosophy

In Chinese philosophy Yin is the complementary feminine part of the Taijitu and is represented by a dark lobe.

Poetry

The use of darkness as a rhetorical device has a long-standing tradition. Shakespeare, working in the 16th and 17th centuries, made a character called the "prince of darkness" (King Lear: III, iv) and gave darkness jaws with which to devour love. (A Midsummer Night's Dream: I, i)[6] Chaucer, a 14th-century Middle English writer of The Canterbury Tales, wrote that knights must cast away the "workes of darkness."[7] In The Divine Comedy, Dante described hell as "solid darkness stain'd."[8]

Language

In Old English there were three words that could mean darkness: heolstor, genip, and sceadu.[9] Heolstor also meant "hiding-place" and became holster. Genip meant "mist" and fell out of use like many strong verbs. It is however still used in the Dutch saying "in het geniep" which means secretly. Sceadu meant "shadow" and remained in use. The word dark eventually evolved from the word deorc.[10]

Greek mythology

Erebus was a primordial deity in Greek Mythology, representing the personification of darkness.

See also

References

- ↑ "W. Wundt (1907): Outlines of Psychology - 6. Pure sensations.". uni-leipzig.de.

- ↑ Horner, David T. (2000). Demonstrations of Color Perception and the Importance of Contours, Handbook for Teaching Introductory Psychology. 2. Texas: Psychology Press. p. 217.

Afterimages are the complementary hue of the adapting stimulus and trichromatic theory fails to account for this fact

- ↑ Mantese, Lucymarie (March 2000). "Photon-Driven Localization: How Materials Really Absorb Light". American Physical Society. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ↑ Barger, Andrew (2014). Mesaerion: The Best Science Fiction Short Stories 1800-1849. Bottletree Books LLC. pp. 45–59. ISBN 978-1-933747-49-1.

- ↑ "Online translation of The Quran". Retrieved November 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Shakespeare, William. "The Complete Works". The Tech, MIT.

- ↑ Chaucer, Geoffrey (14th century). The Canterbury Tales, and Other Poems. The Second Nun's Tale. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Alighieri, Dante; Francis, Henry, translator (14th century). The Divine Comedy. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Mitchell, Bruce; Fred C. Robinson (2001). A Guide to Old English. Glossary: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 332, 349, 363, 369. ISBN 0-631-22636-2.

- ↑ Harper, Douglass (November 2001). "Dark". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

External links

The dictionary definition of darkness at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of darkness at Wiktionary Quotations related to Darkness at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Darkness at Wikiquote Media related to Darkness at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Darkness at Wikimedia Commons