Delaunay triangulation

In mathematics and computational geometry, a Delaunay triangulation for a set P of points in a plane is a triangulation DT(P) such that no point in P is inside the circumcircle of any triangle in DT(P). Delaunay triangulations maximize the minimum angle of all the angles of the triangles in the triangulation; they tend to avoid sliver triangles. The triangulation is named after Boris Delaunay for his work on this topic from 1934.[1]

For a set of points on the same line there is no Delaunay triangulation (the notion of triangulation is degenerate for this case). For four or more points on the same circle (e.g., the vertices of a rectangle) the Delaunay triangulation is not unique: each of the two possible triangulations that split the quadrangle into two triangles satisfies the "Delaunay condition", i.e., the requirement that the circumcircles of all triangles have empty interiors.

By considering circumscribed spheres, the notion of Delaunay triangulation extends to three and higher dimensions. Generalizations are possible to metrics other than Euclidean. However, in these cases a Delaunay triangulation is not guaranteed to exist or be unique.

Relationship with the Voronoi diagram

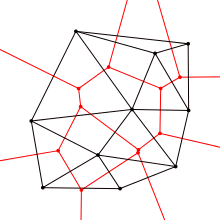

The Delaunay triangulation of a discrete point set P in general position corresponds to the dual graph of the Voronoi diagram for P. Special cases include the existence of three points on a line and four points on circle.

-

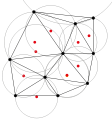

The Delaunay triangulation with all the circumcircles and their centers (in red).

-

Connecting the centers of the circumcircles produces the Voronoi diagram (in red).

d-dimensional Delaunay

For a set P of points in the (d-dimensional) Euclidean space, a Delaunay triangulation is a triangulation DT(P) such that no point in P is inside the circum-hypersphere of any simplex in DT(P). It is known[1] that there exists a unique Delaunay triangulation for P if P is a set of points in general position; that is, the affine hull of P is d-dimensional and no set of d + 2 points in P lie on the boundary of a ball whose interior does not intersect P.

The problem of finding the Delaunay triangulation of a set of points in d-dimensional Euclidean space can be converted to the problem of finding the convex hull of a set of points in (d + 1)-dimensional space, by giving each point p an extra coordinate equal to |p|2, taking the bottom side of the convex hull, and mapping back to d-dimensional space by deleting the last coordinate. As the convex hull is unique, so is the triangulation, assuming all facets of the convex hull are simplices. Nonsimplicial facets only occur when d + 2 of the original points lie on the same d-hypersphere, i.e., the points are not in general position.

Properties

Let n be the number of points and d the number of dimensions.

- The union of all simplices in the triangulation is the convex hull of the points.

- The Delaunay triangulation contains O(n⌈d / 2⌉) simplices.[2]

- In the plane (d = 2), if there are b vertices on the convex hull, then any triangulation of the points has at most 2n − 2 − b triangles, plus one exterior face (see Euler characteristic).

- In the plane, each vertex has on average six surrounding triangles.

- In the plane, the Delaunay triangulation maximizes the minimum angle. Compared to any other triangulation of the points, the smallest angle in the Delaunay triangulation is at least as large as the smallest angle in any other. However, the Delaunay triangulation does not necessarily minimize the maximum angle.[3] The Delaunay triangulation also does not necessarily minimize the length of the edges.

- A circle circumscribing any Delaunay triangle does not contain any other input points in its interior.

- If a circle passing through two of the input points doesn't contain any other of them in its interior, then the segment connecting the two points is an edge of a Delaunay triangulation of the given points.

- Each triangle of the Delaunay triangulation of a set of points in d-dimensional spaces corresponds to a facet of convex hull of the projection of the points onto a (d + 1)-dimensional paraboloid, and vice versa.

- The closest neighbor b to any point p is on an edge bp in the Delaunay triangulation since the nearest neighbor graph is a subgraph of the Delaunay triangulation.

- The Delaunay triangulation is a geometric spanner: the shortest path between two vertices, along Delaunay edges, is known to be no longer than times the Euclidean distance between them.

Visual Delaunay definition: Flipping

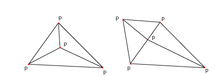

From the above properties an important feature arises: Looking at two triangles ABD and BCD with the common edge BD (see figures), if the sum of the angles α and γ is less than or equal to 180°, the triangles meet the Delaunay condition.

This is an important property because it allows the use of a flipping technique. If two triangles do not meet the Delaunay condition, switching the common edge BD for the common edge AC produces two triangles that do meet the Delaunay condition:

-

This triangulation does not meet the Delaunay condition (the sum of α and γ is bigger than 180°).

-

This triangulation does not meet the Delaunay condition (the circumcircles contain more than three points).

-

Flipping the common edge produces a Delaunay triangulation for the four points.

This operation is called a flip, and can be generalised to three and higher dimensions.[4]

Algorithms

Many algorithms for computing Delaunay triangulations rely on fast operations for detecting when a point is within a triangle's circumcircle and an efficient data structure for storing triangles and edges. In two dimensions, one way to detect if point D lies in the circumcircle of A, B, C is to evaluate the determinant:[5]

When A, B and C are sorted in a counterclockwise order, this determinant is positive if and only if D lies inside the circumcircle.

Flip algorithms

As mentioned above, if a triangle is non-Delaunay, we can flip one of its edges. This leads to a straightforward algorithm: construct any triangulation of the points, and then flip edges until no triangle is non-Delaunay. Unfortunately, this can take O(n2) edge flips.[6] While this algorithm can be generalised to three and higher dimensions, its convergence is not guaranteed in these cases, as it is conditioned to the connectedness of the underlying flip graph: this graph is connected for two dimensional sets of points, but may be disconnected in higher dimensions.[4]

Incremental

The most straightforward way of efficiently computing the Delaunay triangulation is to repeatedly add one vertex at a time, retriangulating the affected parts of the graph. When a vertex v is added, we split in three the triangle that contains v, then we apply the flip algorithm. Done naïvely, this will take O(n) time: we search through all the triangles to find the one that contains v, then we potentially flip away every triangle. Then the overall runtime is O(n2).

If we insert vertices in random order, it turns out (by a somewhat intricate proof) that each insertion will flip, on average, only O(1) triangles – although sometimes it will flip many more.[7] This still leaves the point location time to improve. We can store the history of the splits and flips performed: each triangle stores a pointer to the two or three triangles that replaced it. To find the triangle that contains v, we start at a root triangle, and follow the pointer that points to a triangle that contains v, until we find a triangle that has not yet been replaced. On average, this will also take O(log n) time. Over all vertices, then, this takes O(n log n) time.[8] While the technique extends to higher dimension (as proved by Edelsbrunner and Shah[9]), the runtime can be exponential in the dimension even if the final Delaunay triangulation is small.

The Bowyer–Watson algorithm provides another approach for incremental construction. It gives an alternative to edge flipping for computing the Delaunay triangles containing a newly inserted vertex.

Divide and conquer

A divide and conquer algorithm for triangulations in two dimensions is due to Lee and Schachter which was improved by Guibas and Stolfi[10] and later by Dwyer. In this algorithm, one recursively draws a line to split the vertices into two sets. The Delaunay triangulation is computed for each set, and then the two sets are merged along the splitting line. Using some clever tricks, the merge operation can be done in time O(n), so the total running time is O(n log n).[11]

For certain types of point sets, such as a uniform random distribution, by intelligently picking the splitting lines the expected time can be reduced to O(n log log n) while still maintaining worst-case performance.

A divide and conquer paradigm to performing a triangulation in d dimensions is presented in "DeWall: A fast divide and conquer Delaunay triangulation algorithm in Ed" by P. Cignoni, C. Montani, R. Scopigno.[12]

Divide and conquer has been shown to be the fastest DT generation technique.[13][14]

Sweephull

Sweephull[15] is a hybrid technique for 2D Delaunay triangulation that uses a radially propagating sweep-hull, and a flipping algorithm. The sweep-hull is created sequentially by iterating a radially-sorted set of 2D points, and connecting triangles to the visible part of the convex hull, which gives a non-overlapping triangulation. One can build a convex hull in this manner so long as the order of points guarantees no point would fall within the triangle. But, radially sorting should minimize flipping by being highly Delaunay to start. This is then paired with a final iterative triangle flipping step.

Applications

The Euclidean minimum spanning tree of a set of points is a subset of the Delaunay triangulation of the same points, and this can be exploited to compute it efficiently.

For modelling terrain or other objects given a set of sample points, the Delaunay triangulation gives a nice set of triangles to use as polygons in the model. In particular, the Delaunay triangulation avoids narrow triangles (as they have large circumcircles compared to their area). See triangulated irregular network.

Delaunay triangulations can be used to determine the density or intensity of points samplings by means of the DTFE.

.svg.png)

Delaunay triangulations are often used to build meshes for space-discretised solvers such as the finite element method and the finite volume method of physics simulation, because of the angle guarantee and because fast triangulation algorithms have been developed. Typically, the domain to be meshed is specified as a coarse simplicial complex; for the mesh to be numerically stable, it must be refined, for instance by using Ruppert's algorithm.

The increasing popularity of finite element method and boundary element method techniques increases the incentive to improve automatic meshing algorithms. However, all of these algorithms can create distorted and even unusable grid elements. Fortunately, several techniques exist which can take an existing mesh and improve its quality. For example, smoothing (also referred to as mesh refinement) is one such method, which repositions nodal locations so as to minimize element distortion. The stretched grid method allows the generation of pseudo-regular meshes that meet the Delaunay criteria easily and quickly in a one-step solution.

Constrained Delaunay Triangulation has found applications in path planning in automated driving [16]

See also

- Beta skeleton

- Constrained Delaunay triangulation

- Delaunay tessellation field estimator

- Flip graph

- Gabriel graph

- Gradient pattern analysis

- Pitteway triangulation

- Urquhart graph

- Voronoi diagram

- Convex hull algorithms

- Quasitriangulation

References

- 1 2 Delaunay, Boris (1934). "Sur la sphère vide". Bulletin de l'Académie des Sciences de l'URSS, Classe des sciences mathématiques et naturelles. 6: 793–800.

- ↑ Seidel, Raimund (1995). "The upper bound theorem for polytopes: an easy proof of its asymptotic version". Computational Geometry. 5 (2): 115–116. doi:10.1016/0925-7721(95)00013-Y.

- ↑ Edelsbrunner, Herbert; Tan, Tiow Seng; Waupotitsch, Roman (1992), "An O(n2 log n) time algorithm for the minmax angle triangulation", SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing, 13 (4): 994–1008, doi:10.1137/0913058, MR 1166172.

- 1 2 De Loera, Jesús A.; Rambau, Jörg; Santos, Francisco (2010). Triangulations, Structures for Algorithms and Applications. Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics. 25. Springer.

- ↑ Guibas, Leonidas; Stolfi, Jorge (1985). "Primitives for the manipulation of general subdivisions and the computation of Voronoi". ACM Transactions on Graphics. 4 (2): 74–123. doi:10.1145/282918.282923.

- ↑ Hurtado, F.; M. Noy; J. Urrutia (1999). "Flipping Edges in Triangulations". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 22 (3). pp. 333–346.

- ↑ Guibas, Leonidas J.; Knuth, Donald E.; Sharir, Micha (1992). "Randomized incremental construction of Delaunay and Voronoi diagrams". Algorithmica. 7: 381–413. doi:10.1007/BF01758770.

- ↑ de Berg, Mark; Otfried Cheong; Marc van Kreveld; Mark Overmars (2008). Computational Geometry: Algorithms and Applications (PDF). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-77973-5.

- ↑ Edelsbrunner, Herbert; Shah, Nimish (1996). "Incremental Topological Flipping Works for Regular Triangulations". Algorithmica. 15 (3): 223–241. doi:10.1007/BF01975867.

- ↑ Computing Constrained Delaunay Triangulations

- ↑ Leach, G. (June 1992). "Improving Worst-Case Optimal Delaunay Triangulation Algorithms.". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.56.2323

.

. - ↑ Cignoni, P.; C. Montani; R. Scopigno (1998). "DeWall: A fast divide and conquer Delaunay triangulation algorithm in Ed". Computer-Aided Design. 30 (5): 333–341. doi:10.1016/S0010-4485(97)00082-1.

- ↑ A Comparison of Sequential Delaunay Triangulation Algorithms http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~jrs/meshpapers/SuDrysdale.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~quake/tripaper/triangle2.html

- ↑ S-hull

- ↑ http://web.mit.edu/mobility/publications/IV2012_Anderson_Karumanchi_Iagnemma.pdf

External links

- Delaunay triangulation in CGAL, the Computational Geometry Algorithms Library:

- Yvinec, Mariette. "2D Triangulation". Retrieved April 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Pion, Sylvain; Teillaud, Monique. "3D Triangulations". Retrieved April 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Hornus, Samuel; Devillers, Olivier; Jamin, Clément. "dD Triangulations".

- Hert, Susan; Seel, Michael. "dD Convex Hulls and Delaunay Triangulations". Retrieved April 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

- Yvinec, Mariette. "2D Triangulation". Retrieved April 2010. Check date values in:

- "Delaunay triangulation". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved April 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)