Delaware, Ontario

| Delaware | |

|---|---|

| Community | |

Delaware | |

| Coordinates: 42°54′30″N 81°25′0″W / 42.90833°N 81.41667°W | |

| Country |

|

| Province |

|

| County | Middlesex County |

| Area | |

| • Total | 97.24 km2 (37.54 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,521 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (67/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| Postal code | N0L 1E0 |

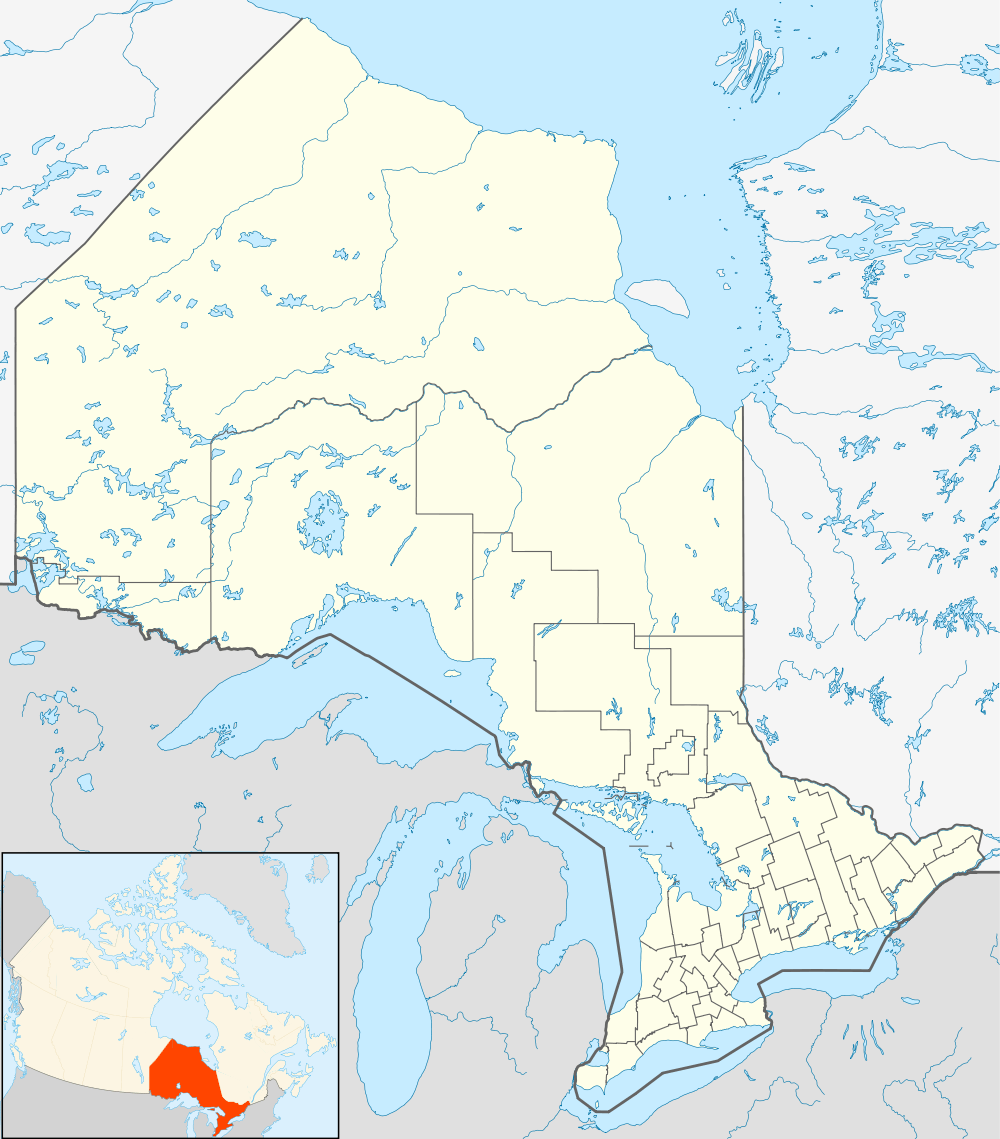

Delaware is a community located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) west of and outside of London, Ontario, Canada within Middlesex County. Delaware straddles the Thames River. Delaware is accessed by the old highway (Highway 2) linking London and Chatham and the freeway (Highway 402) linking Sarnia along with Port Huron and Toronto.

History

Delaware was originally populated by native Indians for centuries before recorded history. In 1615 when the Recollet missionary Reverend Father Joseph le Caron reached the Midland area, the whole vast territory cradled by the Detroit, St. Clair and Niagara Rivers was populated by a branch of the Hurons called the Attawandarons. The early French explorers named them the Neutrals, because of the Attawandaron neutrality between the Iroquois and Hurons in their on-going conflict. Their population may have been as high as sixty thousand, and were settled in many villages and a few large towns, trading with both the Hurons to the north and the Iroquois to the south-east. The Attawandarons are recognized today for their skills in making fine flint instruments such as arrow heads.

During Governor Simcoe's 1793 expedition to and from Niagara to Detroit, Major Edward Littlehales kept a journal in which he kept a running narrative on who and what they saw. En route along the Detroit Path, as the old Indian footpath which led from Lake Ontario through the Mohawk village on the Grand River to the Thames River and down to Detroit, Major Littlehales recorded a “Delaware Castle” along the Thames where they were given a feast of eggs and venison at the encampment of “a Canadian trader”. The Thames River was recorded very early by the French explorers as "La Tranche", and used as the route to Lake St. Clair and Detroit by the traders and loggers well into the 19th century.

By proclamation of Gov. Simcoe in 1792, Upper Canada was divided into 19 counties, one being Middlesex County, which was soon surveyed, leading to the formation of Delaware Township, and its subsequent settlement. In 1798 an Act was passed better dividing the Province into 8 Districts, 23 Counties, and 158 Townships; one of which was London Township. Governor Simcoe's government (the first elected parliament in Upper Canada) in July 1793 passed the Public Highways Act, giving the local Justices of The Peace (Commissioners) power to administer the building of roads and bridges, and the supervision of the construction to persons termed Pathmasters. In 1804 the first public money in the province was appropriated by Government Act 44 Geo. 111 for the improvement of roads and bridges in Upper Canada, and soon by the Act 46th Geo. 111, chap. 4, (1806) 1600 pounds sterling was appropriated for the "improvement of a leading highway through the province, from the Eastern to the Western Districts.” The Act described the road: …”Commencing at the Indian Mill on the Grand River, thence along the road leading through the Township of Burford to the Delaware Town on the River la Tranche, and across the said river, thence down the said river to the Moravian Grant.” It is possible that Gideon Tiffany had some influence on the decision to fund the road, thus opening the avenue for Delaware's expansion after 1806, and establishing the east-west route that would be used by both American and British forces in the War of 1812. In this area the road still bears the name of its first administrator's title: Commissioners Road. Part of the land grant deal for settlers was a requirement to maintain the road abutting their land, or to provide 3 to 12 days labour per year in assisting road maintenance.

Early Delaware Village itself was founded not by settlers from Britain as is commonly thought, but almost entirely by Americans. They, for the most part, were descended from the earliest settlers of Colonial America, survivors of the fittest in a very real sense, and had several generations of cumulative knowledge of how to survive and thrive on the cutting edge of civilization. Some had United Empire Loyalist status, generally having fought for the crown during the American Revolution in Butlers Rangers and the like, and as such received land grants; a few inherited their land, such as Andrew Westbrook; and others including Gideon Tiffany and Moses Brigham purchased their land. Most were frontiersmen, hard, independent, and resourceful, but a few were cultured, educated gentlemen who arrived with resources. Many of the early Delaware settlers had connections, and knew how to use them. All of them shared the attributes of courage and adventure, for Delaware in the late 1700s and early 1800s was true frontier. Detroit and Niagara were the closest areas of populace...and both centers were days of travel away.

Those early settlers had large families, intermarried among themselves, and with the ever-increasing influx of settlers, which after the War of 1812, were increasingly from Britain and Europe.

In 1794, the first white man to settle in Delaware was a frontiersman by the name of Ebenezer Allen, a man who also is historically regarded as the founder of Rochester New York. He was the first white settler in that location, and the builder and operator of the first mill in the Genessee Valley of New York. Ebenezer was instrumental in Indian peace initiatives in that region, and his intelligence and education are evident in his written letters held today in the American Library of Congress. Delaware was his second major stop, although it came late in his life.

Much was written about Ebenezer Allen even during his life, and he was researched by at least two American historians. The first paragraph in historian Donovan Shilling’s book “Rochester’s Romantic Rogue – The Life and Times of Ebenezer Allen” lays a brief but vivid description of his life before Delaware. Shilling wrote “There are many stories written in the world of fiction that are absolutely incredible. Certainly, no tale however tall, can match the real-life escapades of the pioneer rogue, blood brother in the Senecas, notorious guerrilla warrior and irascible lover, Ebenezer "Indian" Allan.”

Mary Jemison, the white woman who was captured as a child in Pennsylvania by the Shawnee Indians and adopted by the Senecas, devoted a whole chapter of the narrative of her life to Ebenezer Allen. He obviously made a large impression on Mary, and she went to great lengths to protect him, thus demonstrating the power of the man's personality.

Morley B. Turpin of Rochester New York, intensively researched Ebenezer and wrote an even more graphic account of his life. Turpin wrote of Ebenezer “In 1789 Allen was 45 years old. He was a tall, straight, vital figure of earth, good looking, light complexioned, with ingratiating manners when he those to use them. He had served during the Revolution in the Tory Ranger regiment of the infamous Col. John Butler and as a lieutenant in the British Indian Department. For that reason he was cordially detested by the settlers who had just won a war for independence. Ebenezer Allen was a product of his environment and that always was harsh and relentless. Without doubt he was shrewd and possibly unscrupulous in his dealings ... Progressive, energetic and keenly alive to his own interests, he was an outstanding figure in Western New York."

He called himself “Eben Allen”, but was commonly known as “Indian Allen” for his familiarity and liking for the Native Americans; particularly the women. Throughout his known life, Ebenezer paid close attention to the Indian maidens: his first two daughters were born to Sally Bull, a sister of Captain Bull, an Indian chief and son of the Delaware Indian leader Teedyuscung. A contemporary in the Rochester New York area, George E. Slocum, wrote of Ebenezer" . . . being 45 years of age, tall and erect, quick of movement and energetic, [he] could appear courageous and affable, was at times loquacious and at others uncommunicative…Allan's chief offense against society was his insane passion for matrimony."

The Genesee pioneer Enos Stone wrote: "In one of the early years I carried some grist to the Allen mill and had to remain overnight. Allen was then on a spree or carousal. To make a feast he had sent some Indians out into the woods to shoot hogs that had gone wild and he furnished the whiskey. Many Indians collected. It was a high time and the chief of the entertainment was enjoying it in high glee. When he tired of the carousal, Ebenezer retired to a couch where a squaw and a white wife awaited his coming."

Although American, Ebenezer took the British side in the American Revolution, and he was renowned for his savagery in raids as one of Butlers Rangers against the American Patriot settlers in the Mohawk and Genessee Valleys; confessing to Mary Jemison and feeling regret in later years for his horrific deeds against men, women and children. He arrived in the Genessee as an agent for the British Indian Department, and although the American settlers called him “Tory Allen”, he was not molested like many Loyalists, likely because of his reputation for violence in Butler’s Rangers. In a letter dated July 29, 1779, by the Rev. Nathan Ker, pastor of the Goshen Presbyterian Church, to Governor Clinton, Rev. Kerr enclosed the examination of a double deserter by the name of Moabury Owen in which Owen listed names of several of the white members of Joseph Brant's raiding party on the Minisink New York, and subsequent massacre of the local militia men who marched from Goshen to meet them. Among the names were Ebenezer Allen and Anthony Westbrook, the father of Andrew Westbrook, later to become notorious during the War of 1812 in the Delaware Ontario area.

For his Revolutionary War service in Butler’s Rangers, and consequent tenure with the British Indian Department, the Executive Council of Upper Canada granted Ebenezer 2000 acres at the mouth of the Dingman Creek in Delaware Township on condition of building a mill, church and school, with an additional grant of 200 acres to each settler that he brought in. In 1793, Ebenezer left his Genessee mill in charge of his brother-in-law Christopher Dugan, and set out from New York State for Delaware, accompanied by his two daughters Chloe and Mary by Sally Bull, his first white wife Lucy Chapman and, their 5-year-old son Seneca, and his other wife Millie Gregory with whom Ebenezer would have six additional children. With him came a group of settlers with livestock and possessions, and they travelled up the old Indian path along the Thames River from Detroit to the location of Delaware, spending a night in Fairfield Village, where Ebenezer was miss-heard and noted in the Missionary’s diary as Ethan Allen rather than Eben. It is unknown if the people that arrived in Delaware with him were genuine settlers or were intended to be Ebenezer’s employees in the lumber and mill business. When Ebenezer Allen arrived in the wilds of Delaware he was about 50 years of age, having already led a very full life. The freedom and independence the old frontiersman sought would be short-lived, as British rules and regulation would soon surround him. Although many of the next arrivals into Delaware Township were American Loyalists like Ebenezer, and some were also veterans of Butlers Rangers, only a handful were unable or unwilling to submit to the new order of autocratic British rule that came to this area. Most notably, these local War of 1812 American rebels were Ebenezer Allen, Andrew Westbrook, whose father Anthony had been a white raider with Joseph Brandt’s Indian Department during the Revolution, and Simon Watson. Ebenezer’s son Seneca Allen, who married Fannie Lucinda Brigham, daughter of Moses Brigham and Lucinda Tiffany, sister of Gideon Tiffany, also went to the American side during the war. On page 202 of John Brandt Mansfield’s book “The History of the Great Lakes”, it states that Seneca “in respect to the Indian Department was of great value to the Government of the United States during the war of 1812.” Seneca and Fannie Lucinda’s daughter Frances Louisa married Benjamin Franklin Hyde, a Michigan Legislator and Judge.

In the meanwhile, Ebenezer Allen constructed his Delaware saw and grist mills, and soon a primitive distillery. He started a community in the Delaware wilderness using nothing but primitive tools, his obvious strength, will and ingenuity. In 1801, due to on-going problems with British authority, he sold most of his Delaware holdings to Moses Brigham and Gideon Tiffany. Ebenezer spent the next decade in and out of trouble with British Authority, and joined the American cause at the outbreak of the War of 1812. British General Brock ordered Daniel Springer of Delaware (who also had been part of Butler's Rangers) to arrest the "disaffected", and Ebenezer was taken into custody and jailed at Turkey Point. Shortly after his release and return to Delaware in 1813, Ebenezer Allen died and is believed to have been buried by his son Seneca on the west bank of the Thames River downstream of the present day Komoka Bridge.

Canadian Historian Daniel J. Brock wrote: “In fact, Allan was neither a saint nor a villain, but simply a product of the frontier – self-reliant, capable, and hardworking, yet short-tempered, vindictive, and cruel. Because he lived close to nature and was primarily motivated by self-interest, his allegiance to higher authority was never strong.”

Thus began the Village of Delaware, its founder Ebenezer Allen a character that could hardly be more colourful and interesting. The wilderness world of Delaware Township that Ebenezer founded his village in was graphically described by one of the next group of settlers into the township: Aaron Kilbourn.

In 1795, two years after the arrival of Ebenezer Allen, the next permanent white settlers moved into Delaware Township from the Susquehanna in Pennsylvania, but having originated in Litchfield Connecticut. They were Joseph Kilbourne and his two sons Timothy and Aaron. The following is a description of Delaware at that time in Aaron’s own words as written years later in “The History and Antiquities of the Name and Family of Kilbourn”

“In 1795, at the age of twenty-two years, I was married in Phelps, Ontario Co., N. Y., to Miss Hannah, daughter of Benjamin Woodhull from Long Island,* and soon after, with my father, brother, and other members, Timothy and myself having sold our property in the United States for 5oo pounds, the family, settled in Delaware, Middlesex County, Canada West. The County of Middlesex at that time was a vast wilderness, inhabited by Indians, who lived by fishing and the chase. The savages were very friendly except when under the influence of ardent spirits, which they often purchased of traders. Our new home was near the banks of the Thames, about one hundred and forty miles west of Niagara Falls. There was not a blacksmith's shop or a mill within sixty miles of us, and the only road was an Indian war-path. There was but one white family in Delaware township, when we arrived. (Ebenezer Allen) We now experi enced the privations, hardships and adventures of pioneer life in a greater degree than we had ever done before. Our clothes soon consisted of a blanket-coat with a belt about the waist, and a mink skin suspended from it, in which we carried a flint, steel, pipe and tobacco ; our pantaloons were made of deer skin, our shirts of calico purchased of the Indian traders. Our food consisted of bear, venison, raccoon and fish. Our bread was made of corn pounded in a hole cut out in the top of a stump, and sifted through a common sieve. Of the fine we made bread, of the coarse, soup. We did not forget the Sabbath ; but usually spent the day in hunting, fishing, drinking watered rum, and playing or fighting with the Indians. The whites and savages sometimes killed each other in their drunken frolics ; but when sober, both parties were ready to make peace. Four or five times a year, the Indians were accustomed to assemble near us, sometimes to the number of six hundred, to celebrate certain feast days — each bringing with him his share of provisions. I was often present at their festivals and weddings. One of the items in their bill of fare was usually a boiled dog. The chief would ask a blessing, thanking the Great Spirit for feeding them, and calling upon Him to feed their children and their children's children. We also frequently attended their funerals. Their practice was to lay the corpse on the ground ; the mourners and other friends were seated in a row ; and one after another, their guns were fired off, for the purpose, as they said, of frightening away the evil spirits, while the good spirits took possession of their friend, and conducted him to their spiritual hunting-grounds. If the deceased was a warrior, they signified the number slain by him, by the blows of a hatchet upon a standing pole. We often joined in these rude ceremonies for the purpose of conciliating our red neighbors, and it had the desired effect. I could use the bow, the hatchet, and the spear, with the best of them; and my brother was designated among them as ' the great white hunter.' ' I have seen more than one hundred deer in a drove, and a flock of wild turkeys ten or a dozen rods wide, and so long that neither end was visible. The pike were so numerous in the streams that we could catch fourteen hundred in a single night, each weighing from three to five pounds. Wolves, too, were abundant. I once met nine gray ones together, and felt constrained to give them a wide path, and to let them pass on unmolested. Our family purchased 3500 acres of land, for $2 50 per acre, to be paid in five or six annual installments— of which sum myself and brother paid one thousand dollars down. We built two saw mills and a grist mill, (at Kilworth) and paid the installments as they became due, for three successive years, and of the last installments I paid my full share. But our dam had been carried off, and other losses pressed heavily upon us, so that a portion of the last payment was not met when due ; and as we were all bound together, we all failed together. My father then removed to the vicinity of Detroit, bought a squatter's privilege upon Rouge River remained there two or three years, and then returned to Delaware, where he died in 1817, aged 72. A few years subsequent, a deed was made out for him at Washington, for 640 acres of land in Michigan; but the Indians robbed the mail and destroyed the deed. This land is occupied, but we have never been able to gain possession of it.* When the war of 1812 broke out, ours was still a frontier settlement. The country was overrun with Indians, accoutred, plucked and painted like devils, as they were — some carrying poles decked with human scalps, which they would leave at our doors, while they came in to take our hard-earned food or our scalps, as best suited their purpose for the time being. Some persons in our vicinity joined the Americans, and came back and robbed us; and our own Indians murdered some of our neighbors, that they might obtain the reward for scalps. The Yankees drove off our horses, the Indians killed our sheep, and the soldiers robbed our hen-roosts. I joined the Canadian forces as a volunteer, and marched to Detroit. At the battle of the River Raisin, one of our British Indians dragged an American soldier who had one leg broken, out of the battle, concealed him in some bushes, until the fight was over, and then placed him on a hand sled and drew him to the American camp, a distance of over thirty miles. You may be sure that by this act the savage was repaying some act of kindness. Other instances of a similar kind, which came under my own observation, I might relate; but the above will suffice as an illustration of a remarkable trait of the aborigines. On my way home, I found a poor American soldier who was wounded at the Raisin battle. One of the Indians attempted to kill him, upon which I stepped between them, and saved his life. From this time he kept close by me while I remained in his company. We carried him ten or twelve miles in our sleig ; and when he could go no farther, we provided him with money and left him in the care of persons who would take the best care of him. We afterwards learned of his death. Soon after we reached home, a regiment passed us on their way to storm Sandusky Fort. They were defeated. Very few came back, and they were fearfully mangled. They were driven right through Delaware. I dragged one poor fellow, with a broken leg, on a sled, five or six miles. The advance of General Harrison caused our army to retreat up the Thames to Moraviantown, where was fought the battle of the Thames, in which Tecumseh was killed. In the defeat of our forces, and the subsequent pursuit, the fugitive army again passed through Delaware. The action between Colonel Croghan and a portion of our army, was but eighteen miles from my home. During the following summer, there was much fighting in our town and vicinity. In the expedition of General McArthur, our mills and the office of my father were burnt. As my father was Town Clerk, the records of the town were destroyed with his office. Peace came at last, but it found us in a condition far from enviable. The loss of time, the almost total neglect of our farms, the ruinous prices which we were compelled to pay for the necessaries of life, the torch of the incendiary, the plunderings of the soldiery and the pillaging of traitorous neighbors, had almost ruined us. In my stock, I was reduced to a single yoke of oxen, one of which I killed for food, and the other I sold to buy flour. For the latter, I sent to Detroit, 120 miles distant — two barrels costing me forty dollars. Before its arrival, we were without bread nine days. I had eight small children to provide for, which was no easy task at such a time. As I have before stated, however, we had an abundance of fish and game, so that we were never destitute of wholesome food. At the close of the war, I drew from government three hundred acres of land in the town of Westminster, upon which I now reside — having removed from Delaware to this place in 1815. My farm is now worth $2,500, and we are surrounded by many blessings and privileges. I had not been long in my new home, when the Methodists came into our neighborhood, and created a great excitement. I determined to drive them from the place, and united with others of a kindred spirit for that purpose. But the more they were persecuted, the stronger they grew; and some of my party told such bare-faced falsehoods concerning them, that I left their company, and finally went to 'quarterly meeting.' Through the instrumentality of these preachers, I was led to consider the error of my former ways, and to seek forgiveness where alone it can be found. I have a hope, by the help of God, to walk worthily, and trust to be found in the narrow road when I am called to a world of less care than this."

In the decade following the coming of the Kilbourn family, Delaware expanded more rapidly with the arrival of Gideon Tiffany.

Gideon Tiffany was a 4th generation American who moved to Canada and became “the King’s Printer” in Niagara on the Lake, and published the Upper Canada Gazette from 1794 to 1797. The British Government suspected him of American sympathies, so in 1797 he resigned King’s Printer and two years later published an independent paper called the Canadian Constellation. In the spring of 1801 Gideon quit the publishing business and with his sister Lucinda's husband Moses Brigham,(a 6th generation American descended from an early Puritan) purchased 2000 plus acres including saw mills from Ebenezer Allen in Delaware on the Thames River. Gideon Tiffany and Brigham paid Ebenezer Allen 3050 pounds sterling in New York Currency, which was a very large sum of money in those days. By 1804 the partners Tiffany and Brigham were trading in furs with the Indians, and were producing up to half a million board feet of lumber a year, which was floated down the Thames River to a booming market in Detroit. After the town of Detroit was devastated by fire in June 1805, Delaware became a boom town as the Detroit's major source of lumber, timber, logs, and shingles. Gideon Tiffany founded his own family dynasty in Delaware, and was a major Delaware Township landowner. In 1812 he was commissioned a lieutenant in the 1st Middlesex Militia, held several public offices in the township in his lifetime, and was the primary in the formation of the first regular mail from Niagara to Delaware every 3 weeks. In 1837 he was a signatory of the Delaware Reform Association and promoted civil disobedience by not paying taxes. Gideon proposed a resolution declaring that provincial delegates to the Toronto convention in December “should be instructed to propose to the Convention to petition Her Majesty to effect a peaceful separation of the Province from the mother country in order to prevent a civil war.” For this act of “Delaware conspiracy’, Gideon was thrown in jail. The record of his trial examination shows his charges included “alleged attempts to spread disaffection among the Indians.” Gideon Tiffany was tried, acquitted, and freed on 7 May 1838. Returning to Delaware, Gideon lived out his life in relative quietness and died the summer of 1854. He is buried in the old pioneer cemetery in Delaware at the bend of the Komoka Road.

The War of 1812 began with a declaration of war by the United States against the United Kingdom, Ireland and the British Colonies. The war lasted 32 months, ended with no change in boundaries, was fought on 3 theaters…the sea, the extreme southern US notably New Orleans, and regionally along the entire frontier boundary between the US and Canada. It started for several cumulative reasons: American humiliation by Americans sailors continually being “seajacked” and pressed into service on British warships, active British support for Indian resistance against American expansion westward into the American interior, severe trade restrictions caused by Britain’s on-going war with America’s ally France, and a general view held since the Revolutionary War that southern Canada really did and should belong to the United States.

The war ended with the Treaty of Ghent; with any seized land being returned to its former country. The important results were the end of northern American expansion ideas, the loss forever of American Indian dreams of stopping the US expansion westward, a much more cohesive Canadian feeling of identity, and most important for Delaware, a British lock hold on south-western Ontario. The pro-American sentiment so prevalent among many of the early settlers of Delaware Township was suppressed, and they had no choice but to become allegiant to the crown or leave for the United States. During the war General Isaac Brock displayed his military wisdom by ordering the old Butler’s Ranger Daniel Springer to arrest the Delaware “disaffected” which meant the arrest of the openly pro-American settler leaders…notably Ebenezer Allen, Andrew Westbrook and Simon Watson. Old Ebenezer was jailed at Turkey Point, but Andrew Westbrook, who caused havoc in this region with his raids on British supporters, was never caught, choosing to burn his own farm located in Delaware on what is now the Delaware Speedway and forfeiting his roughly 4000 acres of land rather than submit to the crown. Andrew Westbrook escaped to Detroit with his family, and lived to become a public official in St. Clair County Michigan, a man of power and respect. Simon Watson also escaped to Detroit, and holds the dubious distinction of being the last white man scalped in Detroit. The great Indian leader Tecumseh died in the Battle of the Thames, the end of a huge influence on the cohesiveness of the Indians that had allied themselves with the British.

The war for Delaware itself was a nightmare of neighbour against neighbour, homes and farms burned, crops and livestock stolen and destroyed, and near famine. An unfortunate aside of Delaware's war was the torching of Delaware town clerk Joseph Kilbourn's home: the records of early Delaware were lost forever.

In the late 1780s Governor Simcoe had promoted settlement in Upper Canada by offering low-cost land grants with an oath of allegiance, and Americans flooded in to take advantage. By the start of the War of 1812, it was estimated that American settlers outnumbered the United Empire Loyalists by roughly 10 to Delaware Township itself, continued after the end of the war to expand with American expatriates, mostly family connections to Delaware’s early families. They were from the long established developed world of Colonial America; arriving here well equipped to settle the area. They were, for the most part, socially compatible and of like background; here for one reason...to advance.

The Moravian missionary/explorer John Hechewelder visited Delaware in 1798 on his overland trek from Niagara to Fairfield Village then on to Detroit. Hechewelder was a descriptive, non-judgemental writer and his observations of his travels give a valuable view of the areas he passed through. “The Travels of John Hechewelder in Frontier America” by Paul A. Wallace is a compilation of part of the journals of John Hechewelder, who was an interesting mixture of missionary, explorer, writer and revolutionary war American patriot spy. Heading west after leaving Niagara, Hechewelder stayed at Joseph Brandt’s settlement on the Grand River, noting Brandt’s refinement and his fine 2 story house. When leaving the next day, Brandt gave him a hand written letter to deliver to Ebenezer Allen in Delaware...illustrating again the extent that things were known...even in the wilderness. Allen had arrived in the unbroken wilderness of Delaware overland through Detroit from the Rochester New York area; yet in 1798 Joseph Brandt both knew his location, and was familiar enough to send him a letter. Given that Ebenezer Allen and Anthony Westbrook had been part of Brandt’s raids on the American settlers along the Mohawk during the Revolutionary war....that letter’s contents would be interesting to know. Hechewelder noted that west of Burford, the blazed trail was often very faint, and the settlers were far and few between. Instead of being of Pennsylvania or New Jersey stock, they were New Englanders, ideally suited for clearing the wilderness with their outstanding physiques, and ability to persevere in the face of extreme hardship. He described the methods by which the Indians and settlers cleared land....Indians by setting forest fires...and settlers by felling ever-outward from their cabins. Between Burford and Delaware he commented on passing over vast tracts of burned, some still burning land...started by Indians as a method of producing open hunting lands and resulting grazing land for deer. He perceptively viewed the massive clouds of smoke from this custom as the cause of the hazy conditions in eastern America after westerly winds in the spring and fall. Arriving in Delaware, he stayed with Joseph Kilbourn, who already had built a saw mill and grist mill. John Hechewelder named only Kilbourn and Ebenezer Allen but noted that Delaware only 3 years after its inception in the wilderness contained 30 families dwelling on Delaware’s fine lands. Hechewelder noted dryly in his journal that one of Delaware’s leading citizens set a poor example with his morals. Leaving Delaware for his destination of Fairfield Village forty miles down the Thames River, for the first time in his trip having to hire a guide or pilot, Hechewelder encountered the most difficult going of his journey, plaqued by mosquitoes, bogs, ravines, heavy brush and fallen timber. The guide led him astray, which Hechewelder was able to foil with a compass he carried.

For more than 20 years after the War of 1812, Upper Canada was run by a tightly knit, non-elected group of men that were commonly called the Family Compact, led by the like of Anglican or Church of England Bishop of Toronto Bishop Strachan. They were not related by blood, only by their standing at the top of their respective parts of the state: religious, banking, judicial, etc. The Family Compact was very conservative, against US style democracy, instrumental in railroad and canal building, and basically was an upper class club of the privileged that controlled the economy. They ruled in favour of their own opportunism, aided by their connections, and resentment grew among the general population, leading to the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837, led by William McKenzie King.

Delaware Village’s own Dr. Charles Duncombe, a Connecticut Yankee who moved to Delaware about 1819, and in 1824 established in St. Thomas the first medical school in Upper Canada, was a leader of the Patriot War. In December 1837, Duncombe heard reports of Mackenzie's rebellion in Toronto. Duncombe, with several other leaders including Alvaro Ladd, a Vermont Yankee who had settled in Delaware in 1814, and ran the first stagecoach from Delaware to Ancaster, and Joshua Doan from Sparta near Port Stanley, mustered around 200 men in early December and started a march on Toronto. This was called the Western Uprising, but it fell apart near Hamilton when they learned that Mackenzie had been defeated, and Col. Allan MacNab’s militia was moving to meet them. At that point Dr. Duncombe with most of the leaders fled to the US, where Duncombe was the key organizer in Cleveland of the Hunters Lodge, a military organization based at its Grand Lodge there. The Grand Lodge rose to a total of more than 40,000 men in its semi-secret Lodges around the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence. In 1838–39 they came close to bringing Canada and the US to war, launching their own Patriot War in 1838, declaring their own provisional Republic of Canada at a Cleveland convention in September 1838, and establishing a Republican Bank of Canada. Commanded by “commander in chief" Lucius Venus Bierce and "general” William Putnam of Dorchester (William Putnam was the son of Seth Putnam, one of Oxford Counties earliest settlers from the US. William was a Canadian veteran of the War of 1812, having fought in the battles of Lundy's Lane and Queenston Heights, had been a captain of the militia in London, and a Grand Master of the Masonic Lodge. He also owned a gristmill, a distillery and a tavern. William Putnam had chaired at least one political meeting in Delaware), they raided Windsor on December 4, 1838, burning the steamer Thames, and killing a few resident of the town, before the raid ended in a rout and the death by gunshot of William Putnam. Forty-four of the raiders went to trial, and in February 1839, 6 of the raiders including Joshua Doan of Sparta, near Port Stanley, and Amos Perley were hanged in London, and most of the rest were transported (banished)to Australia.

The Rebellion and Patriot War led directly to the British North American Act, which on July 1, 1867, unified and established Canada as a country. Britain still retained Legislative and Foreign Policy control: full Canadian control over its own constitution was not enacted until The Canada Act of 1982.

Education

Delaware has two elementary schools, Delaware Central Public School (Thames Valley District School Board), and Our Lady of Lourdes (London District Catholic School Board). Delaware Central has about 175 students, while Our Lady of Lourdes has approximately 350.[1] In the fall of 2011, Our Lady of Lourdes moved to a new facility on Wellington Street in Delaware. Delaware also has a private school, Riverbend Academy, located on Gideon Drive. Riverbend Academy is co-ed elementary and secondary school offering enrollment from Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12.

Geography

Delaware is nestled in the Thames River Valley, although it has now expanded over the top of the valley ridge. Most of the area surrounding Delaware is made up of forests and floodplain areas. Corn, soybeans and tobacco are farmed extensively in the area around Delaware, as well as inside the town limits in some areas. Delaware has undergone modest growth in housing over the last 30 years, with the developed area nearly doubling in that time.

Many of the buildings in the heart of Delaware are known to be well into their second century. For example, the fine brick house on the north brow of Wellington St. was built in 1842 by the Tiffanys. Buildings in the village still stand that are seen in Civil War era photographs. These include the building that is now Delaware Variety as well as the antique shop across the street. Belvoir Manor is a private home that was at one point a seminary and a private school for boys, and at one point was damaged by fire. Belvoir was originally built by Dean Tiffany in 1859 and named Maple Grove, passing in turn to the Gibson family who renamed it Belvoir and pronounced it Beever, then to the Little family, who after the death of Senator Little sold it to the Roman Catholic Church. Belvoir is now a privately owned farm.

Tourism and entertainment

Delaware boasts a number of tourist destinations despite its small size. Delaware Speedway is a half-mile paved race track that is one of the oldest in Canada. The track hosts stock car racing every Friday night during the summer, as well as several Saturday and Sunday race features. The track has also hosted major concert events in the past including I Mother Earth and Matthew Good.

The Longwoods Road Conservation Area features Skah-Nah-Doht, a recreated Iroquoian village complete with longhouses and tours, as well as a museum featuring exhibits of Iroquoian culture and archaeological artifacts. The park hosts a yearly native festival as well as a re-enactment of the Battle of Longwoods.