A Descent into the Maelström

| "A Descent into the Maelström" | |

|---|---|

|

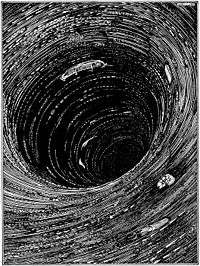

Artist Harry Clarke's 1919 illustration for "A Descent into the Maelström" | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Science Fiction |

"A Descent into the Maelström" is an 1841 short story by Edgar Allan Poe. In the tale, a man recounts how he survived a shipwreck and a whirlpool. It has been grouped with Poe's tales of ratiocination and also labeled an early form of science fiction.

Plot

Inspired by the Moskstraumen, it is couched as a story within a story, a tale told at the summit of a mountain climb in Lofoten, Norway. The story is told by an old man who reveals that he only appears old—"You suppose me a very old man," he says, "but I am not. It took less than a single day to change these hairs from a jetty black to white, to weaken my limbs, and to unstring my nerves." The narrator, convinced by the power of the whirlpools he sees in the ocean beyond, is then told of the "old" man's fishing trip with his two brothers a few years ago.

Driven by "the most terrible hurricane that ever came out of the heavens", their ship was caught in the vortex. One brother was pulled into the waves; the other was driven mad by the horror of the spectacle, and drowned as the ship was pulled under. At first the narrator only saw hideous terror in the spectacle. In a moment of revelation, he saw that the Maelström is a beautiful and awesome creation. Observing how objects around him were attracted and pulled into it, he deduced that "the larger the bodies, the more rapid their descent" and that spherical-shaped objects were pulled in the fastest. Unlike his brother, he abandoned ship and held on to a cylindrical barrel until he was saved several hours later. The "old" man tells the story to the narrator without any hope that the narrator will believe it.

Analysis

The story's opening bears a similarity to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798): in both, an excited old man tells his story of shipwreck and survival.[1] The tale is one of sensation, emphasizing the narrator's thoughts and feelings, especially his terror of being killed in the whirlpool.[2] The narrator uses his reasoning skills to survive and the story is considered one of Poe's early examples of science fiction.[3] The maelstrom's attractive power forecasts certain aspects of the Black Hole theory.

Major themes

- Ratiocination (see also "The Mystery of Marie Roget", "The Purloined Letter", C. Auguste Dupin)

- Sea tale (see also The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, "MS. Found in a Bottle", "The Oblong Box")

- Story within a story (see also "The Oval Portrait")

Allusions

The story mentions Jonas Danilssønn Ramus, a man from Norway who wrote about a famous maelström at Saltstraumen. The opening epigraph is quoted from an essay by Joseph Glanvill called "Against Confidence in Philosophy and Matters of Speculation" (1676), though Poe altered the wording significantly.[4]

Publication history

The story first appeared in the May 1841 edition of Graham's Magazine, published in April.[5] Poe rushed to complete the story in time and later admitted that the conclusion was imperfect.[6] Shortly after Poe's story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" was translated into French without acknowledgment, French readers were seeking out other Poe works and "A Descent into the Maelström" was amongst the earliest translated.[7] Like his other sea adventure works The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and The Journal of Julius Rodman, "A Descent into the Maelström" was believed by readers to be true and one passage was reprinted in the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica – ironically, it was based on a passage that Poe had lifted from an earlier edition of that same encyclopedia.[6] In June 1845, "A Descent into the Maelström" was collected for the first time as part of Poe's Tales, published by G. P. Putnam's Sons Wiley & Putnam, and also included eleven of his other stories.[8]

Critical response

Shortly after its publication, the April 28 issue of the Daily Chronicle included the notice: "The 'Descent into the Maelstroom' [sic] by Edgar A. Poe, Esq., is unworthy of the pen of one whose talents allow him a wider and more ample range."[9] Mordecai M. Noah in Evening Star, however, said the tale "appears to be equal in interest with the powerful article from his pen in the last number, 'The Murder in the Rue Morgue'".[9]

Adaptations

In 1953, Pianist Lennie Tristano recorded "Descent into the Maelstrom", inspired by the short story. It was an improvised solo piano piece that used multitracking and had no preconceived harmonic structure, being based instead on the development of motifs.[10]

In 1986, American composer Philip Glass wrote music inspired by "A Descent into the Maelström". It was commissioned by the Australian Dance Theatre.

Arthur C. Clarke wrote the short story "Maelstrom II" inspired by Poe's story.[11] It was first published by Playboy magazine, and can also be found in Clarke's anthology, The Wind from the Sun.

In 1968, Editora Taika (Brazil) published a comic adaptation in Album Classicos De Terror #7, "Descida No Maelstrom!". Adaptation was by Francisco De Assis, art was by Edegar & Ignacio Justo. It was reprinted in Zarapelho #3 in 1976.

In 1974, Skywald published a comic adaptation in Psycho #18. Adaptation was by Al Hewetson, art was by Cesar Lopez Vera. It was reprinted by Ibero Mundial De Ediciones (Spain) in Dossier Negro #66 (1974), and by Eternity Comics in Edgar Allan Poe: The Pit And The Pendulum And Other Stories #1 in 1988.

In 1975, Warren Publishing published a comic adaptation in Creepy #70. Adaptation was by Richard Margopoulos, art was by Adolpho Usero Abellan. This version has been reprinted multiple times.

In 1993, Novedades Editores (Mexico) published a comic adaptation in Clasicos De Terror #4, "Cayendo En El Maestrom". Adapter & artist unknown.

References in literary works

In 1970, Czechoslovakian writer Ludvík Vaculík made many references to "A Descent into the Maelström" as well as "The Black Cat" in his novel The Guinea Pigs. In Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano, Paul Proteus thinks to himself "Descent into the Maelstrom" as he succumbs to the will of his wife.[12]

References

- ↑ Sova 2001, p. 66

- ↑ Silverman 1991, p. 169

- ↑ Tresh 2002, pp. 116–117

- ↑ Sova 2001, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Bittner 1962, p. 164

- 1 2 Meyers 1992, p. 125

- ↑ Silverman 1991, p. 320

- ↑ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 540

- 1 2 Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 324

- ↑ Shim, Eunmi (2007). Lennie Tristano – His Life in Music. University of Michigan Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-472-11346-0.

- ↑ Arthur Clarke's Maelstrom II. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ Vonnegut 1952, p. 184

Sources

- Bittner, William (1962). Poe: A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09686-7.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1038-6.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092331-0.

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work (Paperback ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-8160-4161-9.

- Thomas, Dwight; Jackson, David K. (1987). The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1809-1849. New York: G. K. Hall & Co. ISBN 978-0-7838-1401-8.

- Tresh, John (2002). "Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction". In Hayes, Kevin J. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–132. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- Vonnegut, Kurt (1952). "18". Player Piano. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Publication history of "A Descent into the Maelström" at the Edgar Allan Poe Society

- Information about Philip Glass's musical interpretation.

-

Descent Into The Maelstrom public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Descent Into The Maelstrom public domain audiobook at LibriVox