Devonshire House

Devonshire House in Piccadilly was the London residence of the Dukes of Devonshire in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was built for William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire in the Palladian style, to designs by William Kent. Completed circa 1740, empty after World War I, it was demolished in 1924.

Many of Britain's great peers maintained large London houses that bore their names. As a ducal house (only in mainland Europe were such houses referred to as palaces), Devonshire House was one of the largest and grandest, ranking alongside Burlington House, Montague House, Lansdowne House, Londonderry House, Northumberland House, and Norfolk House. All of these have been long demolished, except Burlington and Lansdowne, both of which have been substantially altered.

Today the site is occupied by an office building known as Devonshire House.

The site

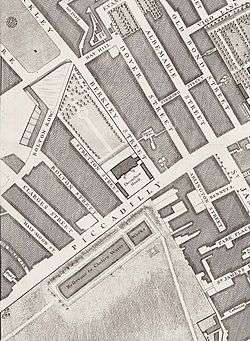

Devonshire House was built on the site of Berkeley House, which John, Lord Berkeley, erected at a cost of over £30,000 on his return from his tenure of the viceroyalty of Ireland; it was constructed from 1665 to 1673. The house was later occupied by Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, a mistress of Charles II.

The house, a classical mansion built by Hugh May, had been purchased by William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire in 1696 and subsequently renamed Devonshire House. As part of the agreement, Lord Berkeley undertook not to build on that part of the land he retained that lay directly behind the house, so keeping the Duke's view. This agreement was continued when the Berkeley land was developed after 1730, and the gardens of Berkeley Square are the termination of that undeveloped strip; to the south the gardens of Lansdowne House were originally also part of it.[1]

On 16 October 1733, the former Berkeley House, while undergoing refurbishment, was completely destroyed by fire, despite firefighting efforts by the Guards, led by Willem van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle, and others led by Frederick, Prince of Wales. The cause was attributed to careless labourers.[2] Ironically, the Duke's former London residence, Old Devonshire House, at 48 Boswell Street, Bloomsbury, survived both its successors until the Blitz of World War II.

Ethos

During the 18th century, existing forms of entertainment began to change and large sophisticated receptions came into fashion, often taking the form of concerts and balls. Initially, hosts would hire one of many new assembly rooms built to indulge the fashion. However, it was not long before the more frequent and wealthy hosts began to add a ballroom to their town houses and the more wealthy still to forsake their smaller town houses in favour of a new and vast palace designed purely for entertaining. The Duke of Devonshire, an owner of vast estates, belonged to the latter category.[3] Thus the fire of the Devonshire House in 1733 provided the opportunity to build a house at the height of contemporary fashion.

For his architect, the 3rd Duke chose the fashionable architect William Kent, for whom this was a first commission for a London house. The house was constructed between 1734 and about 1740.[4] Kent was the protegee of the immensely cultivated 3rd Earl of Burlington and had worked at Chiswick House, built by the 3rd Earl in 1729, and also at Devonshire House's near contemporary Holkham Hall, completed circa 1741, both in the Palladian style; these houses were at the time considered the epitome of fashion and sophistication. Chiswick House was later to come, other estates, into the Devonshires' possession through the marriage of the 4th Duke to Lady Charlotte Boyle, daughter of Lord Burlington.[5]

Architecture

In typical Palladian fashion, Devonshire House consisted of a corps de logis flanked by service wings. The severity of the design, of three storeys in eleven bays, caused one contemporary critic to liken the mansion to a warehouse,[6] and a modern biographer of Kent to remark its "plain severity".[7] However, the curiously flat exterior concealed Kent's sumptuous interiors; these housed a large part of the Devonshire art collection, considered one of the finest in the United Kingdom,[8] and a renowned library,[9] housed in a room 40 ft long: among its treasures was Claude Lorraine's Liber Veritatis, his record in sketches of a lifetime of painting. In the Duke's sitting room, a glass case over the chimneypiece contained the best of his collection of engraved gems and Renaissance and Baroque medallions.[10] Such a prominent commission could hardly fail to be included in Vitruvius Britannicus.[11]

The plan of Devonshire House defines it as one of the earliest of the great 18th-century town houses; at this time the design of a large town house was identical to that of a country house of the same period. Its purpose, too, was identical, to display wealth and consequently power. Thus a great town house, by its size and design, accentuated its owner's power by its contrast with the monotony of the smaller terraced houses surrounding it.[12]

At Devonshire House, Kent's exterior stairs led up to a piano nobile, where the entrance hall was the only room that rose through two storeys.[13] Inconspicuous pairs of staircases are tucked into modest sites at either hand, for the upstairs was strictly private. Enfilades of interconnecting rooms, of which the largest space is devoted to the library, flank central halls, adjusting the traditions of the symmetrical Baroque state apartments, a design which did not lend itself to large gatherings; a few years later such architects as Matthew Brettingham pioneered a more compact design, with a suite of connecting reception rooms circling a central top-lit stair hall - this allowed guests to "circulate". Greeted at the head of the stairs, they then flowed in a convenient circuit rather retracing their steps. This design was first exemplified by the now-demolished Norfolk House completed in 1756.[14] Therefore, it seems that Devonshire House was old-fashioned and unsuited to its intended use almost from the moment of its completion. Thus, from the late 18th century, its interiors were vastly altered.

Usage

Alterations were made to Devonshire House by James Wyatt, over a long period, 1776–90,[15] and later by Decimus Burton, who constructed a new portico, entrance hall and grand stair for the 6th Duke, in 1843.[16] At this time, the external double staircase was swept away, allowing formal entrance to be made to the ground floor through the new portico. Hitherto, the ground floor had contained only secondary rooms and in 18th century fashion been the domain of servants. The new staircase conveyed guests directly to the piano nobile, from a low entrance hall, in a newly created recess formed by creating a bow at the centre of the rear garden facade.[17] Known as the "Crystal Staircase", it had a glass handrail and newel posts.[18] Burton amalgamated several of the principal rooms; he created a vast heavily gilded ballroom from two former drawing rooms and often created double height rooms at the expense of the bedrooms above, causing the house to become even more of a place for display and entertaining rather than for living.

Devonshire House was the setting for a brilliant social and political life, in the circle round William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire and his duchess, Lady Georgiana Spencer, Whig supporters of Charles James Fox.[19]

In 1897, a large fancy dress ball at Devonshire House celebrated Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. The guests, including Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and the Princess of Wales, were dressed as historical portraits come to life. The many portrait photographs taken at the ball have illustrated countless books on the social history of the late Victorian era.[20]

Demolition

Following World War I, many aristocratic families gave up their London houses, and Devonshire House was no exception; it was deserted in 1919.[21] The demolition was mentioned several times nostalgically in literature. It caused Virginia Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway to think "Devonshire House, without its gilt leopards", (a reference to the house's gilded gates) as she passed down Piccadilly,[22] and more notably, inspired Siegfried Sassoon's "Monody on the Demolition of Devonshire House".[23]

The reason for abandonment was that the 9th Duke was the first of his family to have to pay death duties; these amounted to over £500,000. Additionally, he inherited the debts of the 7th Duke. This double burden required the sale of many of the family's valuables, including books printed by William Caxton, many Shakespeare 1st editions,[24] and Devonshire House with its even more valuable three acres of gardens. The sale was finalised in 1920, for a price of £750,000,<ref name="ODNB"/ and the house demolished.[25] The two purchasers were Shurmer Sibthorpe and Lawrence Harrison, wealthy industrialists who developed the site, subsequently building a hotel and block of flats. When told that the proposed demolition was an act of vandalism, Sibthorpe, echoing the building's 18th century critics, replied: "Archaeologists have gathered round me and say I am a vandal, but personally I think the place is an eyesore." [26]

Legacy

_1.jpg)

In 1924-1926, Holland, Hannen & Cubitts built a new office building fronting Piccadilly on the site, which is also known as Devonshire House.[27] The building became the headquarters of Rootes Group, a major automobile manufacturer, with showrooms occupying the ground floor. Rootes Group remained the chief occupant of the building until the 1960s. During World War II, it was also the headquarters of the War Damage Commission.

Some of the paintings and furniture are now at the Devonshire principal seat, Chatsworth House. The wrought-iron entrance gates, between piers with rusticated quoins topped with seated sphinxes, have been re-erected across Piccadilly, to form an entrance to Green Park. The wine cellar is now the ticket office of Green Park tube station. Other architectural salvage included doorways, mantelpieces, and furniture which were relocated to Chatsworth. Some of these stored items were auctioned by Sotheby's on 5–7 October 2010.[28] In the sale, five William Kent chimneypieces from Devonshire House were described by the auctioneer Lord Dalmeny as being of special interest and value: "You can't buy them because they are all in listed buildings now. It's like being able to commission Rubens to paint your ceiling." [29]

Most of the short series of great detached houses of aristocrats which once populated the West End of London, where even the grandest were likely to live in a terraced house, including Devonshire House, Norfolk House and Chesterfield House, are today among England's thousands of lost houses. Lansdowne House lost its front to a street-widening scheme. Just a few remain, but in corporate or state ownership. Marlborough House passed to the crown in the 19th century. Apsley House remains, but is a museum on a small traffic bound island, its gardens long gone, with the family only occupying the uppermost floor. Spencer House is an event venue. Manchester House houses the Wallace Collection. Bridgewater House, Westminster by Charles Barry is now used as offices. Currently, Dudley House is the only one of London's surviving aristocratic private palaces to be occupied and used as its design intended.[30]

References

- ↑ 'Berkeley Square, North Side,' in Survey of London: Volume 40, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings), ed. F H W Sheppard (London: London County Council, 1980), 64-67, accessed November 21, 2015, online

- ↑ London Online; Berkeley House and Devonshire House retrieved 30 September 2010; Sykes, Christopher Simon. Private Palaces: Life in the Great London Houses, p. 98, Chatto & Windus, 1985

- ↑ Girouard, p194 explains this phenomenon.

- ↑ Howard Colvin A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600-1840, 3rd ed. 1995, s.v. "Kent, William".

- ↑ Chatsworth, p52. "The Dowager Duchess of Devonshire". Derbyshire Countryside Ltd. 2005

- ↑ E. Beresford Chancellor, The Private Palaces of London. Chapter E: "It is spacious, and so are the East India Company's Warehouses."

- ↑ Michael I. Wilson, William Kent, Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685—1748 1984:172, who adds "the fact that the house was hidden from public gaze behind a high wall must have helped still further to give it the appearance of a penitentiary"

- ↑ Its nucleus, hung in the earlier house on the site, was noted by Pierre-Jacques Fougeroux, a copy of whose manuscript Voyage survives in the library of the Victoria and Albert Museum; Francis Russell, "Early Italian Pictures and Some English Collectors", The Burlington Magazine 136 No. 1091 (February 1994;85-90) notes fashionable Tintorettos and Veroneses and Raphaels and some less-expected quattrocento paintings including a so-called Bellini.

- ↑ B. Lambert, The History and Survey of London and its Environs, 1806:529.

- ↑ Noted in a brief notice in The Crayon, 1.12 (March 21, 1855:184).

- ↑ Vitruvius Britannicus volume iv (1767, pls. 19 and 20, illustration).

- ↑ Tait A. A. ‘Adam, Robert (1728–1792)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 accessed 4 Oct 2010

- ↑ The great height of the grander saloons pictured in The Illustrated London News was effected in the extensive restructuring under Decimus Burton by taking into the public spaces former upstairs accommodations, making of Devonshire House even more a site purely for public receptions and gallery display.

- ↑ Girouard, pp 194 & 195.

- ↑ Colvin 1995, s.v. "Wyatt, James".

- ↑ Colvin 1995, s.v. "Burton, Decimus".

- ↑ British History Online retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy, "Chatsworth House Auction". Guardian Online, Wednesday 29 September 2010] retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ Hugh Stokes, The Devonshire House Circle, 1916.

- ↑ A light modern memoir of the ball, written by the daughter of the 11th duke and duchess, is Sophia Murphy, The Duchess of Devonshire's Ball, 1984. See also some images of guests in costume here: http://www.rvondeh.dircon.co.uk/incalmprose/index.html

- ↑ Noted by Fiske Kimball, in describing interiors from Lansdowne House re-erected in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, "Lansdowne House Redivivus". The Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, 1943.

- ↑ Virginia Woolf, "Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street", 1923.

- ↑ Richard Davenport-Hines, "Cavendish, Victor Christian William, ninth duke of Devonshire (1868–1938)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 accessed 4 Oct 2010.

- ↑ Now in the Huntington Library, California.

- ↑ Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, p. 54.

- ↑ Laura Battle, "An aristocrat's London residence gives way to modern life, 1925". FT Magazine, August 21, 2010.

- ↑ Holland, Hannen, and Cubitts (1920) The Inception and Development of a Great Building Firm, page 42

- ↑ Sotheby's catalog

- ↑ The Times, Sep 29, 2010; Ben Hoyle, p. 55.

- ↑ A complete list would also include Melbourne House, remodelled as Albany; Dover House in Whitehall, now government offices; Derby House in Stratford Place off Oxford Street; Crewe House,in Curzon Street; Bourdon House at the northeast end of Berkeley Square; Egremont House, Piccadilly, housing the Naval and Military Club; and Bath House. These are mentioned by Nikolaus Pevsner, London I: The Cities of London and Westminster (Buildings of England series) 1962. 78f.

- Trease, George (1975). London. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 161.

See also

Coordinates: 51°30′26″N 0°08′34″W / 51.507270°N 0.142756°W