Nerodia rhombifer

| Nerodia rhombifer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Subfamily: | Natricinae |

| Genus: | Nerodia |

| Species: | N. rhombifer |

| Binomial name | |

| Nerodia rhombifer (Hallowell, 1852) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

N. r. blanchardi (Clay, 1938) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Nerodia rhombifer, commonly known as the diamondback water snake, is a species of nonvenomous natricine colubrid endemic to the central United States and northern Mexico. There are three recognized subspecies of N. rhombifer, including the nominotypical subspecies.

Taxonomy and systematics

The species was first described as Tropidonotus rhombifer by Edward Hallowell in 1852.

Description

Diamondback water snakes are predominantly brown, dark brown, or dark olive green in color, with a black net-like pattern along the back, with each spot being vaguely diamond-shaped. Dark vertical bars and lighter coloring are often present down the sides of the snake. In typical counter colored fashion, the underside is generally a yellow or lighter brown color often with black blotching.

Their dorsal scales are heavily keeled, giving the snake a rough texture. The dorsal scales are arranged in 25 or 27 rows at midbody. There are usually 3 postoculars.[2]

Adult males have multiple papillae (tubercles) on the under surface of the chin, which are not found on any other species of snake in the United States[3]

They grow to an average length of 30-48 inches (76-122 cm). The record length is 69 inches (175.3 cm).[4]

Neonates are often lighter in color, making their patterns more pronounced, and they darken with age.

Habitat

The diamondback water snake is one of the most common species of snake within its range. It is found predominantly near slow moving bodies of water such as streams, rivers, ponds, or swamps.

Diet

Its primary diet is fish and amphibians, specifically slow fish, crayfish, amphiumas (eel-like salamanders), frogs and toads.

Behavior

When foraging for food they will hang on branches suspended over the water, dipping their head under the surface of the water, until they encounter a fish or other prey. They are frequently found basking on these branches over water, and when approached, they will quickly drop into the water and swim away. If cornered, they will often hiss, and flatten their head or body to appear larger. They only typically resort to biting if physically harassed or handled. Its bite is known to be quite painful due to its sharp teeth meant to keep hold of slippery fish. Unfortunately, this defensive behavior is frequently misinterpreted as aggression and often leads to their being mistaken for the venomous cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus), with whom they do share habitat in some places. The brown/tan coloration and diamond-shaped pattern also causes these snakes to be mistaken for rattlesnakes, especially when encountered on land by individuals unfamiliar with snakes.

Geographic range

The diamondback water snake is found in the central United States, predominantly along the Mississippi River valley, but its range extends beyond that. It ranges within the states of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, and Alabama. It is also found in northern Mexico, in the states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz.

This snake was introduced to Lafayette Reservoir in Contra Costa County, California. First observed in the late 1980's, the population reached high densities in the early 1990's, bringing complaints from fisherman and other visitors who believed the non-native snakes were eating the reservoir's fish, frogs and turtles (which mostly consist of non-native stocked fish, non-native American Bullfrogs, and non-native Red-Eared Sliders.) In 1996 a contract was awarded to a wildlife control company to begin to control the snake population. Just the control effort began in December, 1997, large numbers of dead watersnakes and turtles were observed. The cause of the die-off is unknown, but dissected snakes were found to contain a respiratory tract fungus. An abnormally wet and cold El Niño weather system has been indicated as a possible cause for the outbreak. No watersnakes have been confirmed at Lafayette Reservoir since late 1999, but sightings are occasionally reported, and the population may still continue to hang on in low numbers. [5]

Reproduction

Like other Nerodia species, diamondback water snakes are ovoviviparous. They breed in the spring and give birth in the late summer or early fall. Neonates are around 8–10 in (20–25 cm) in length. Though their range overlaps with several other species of water snake, interbreeding is not known.

Conservation concerns

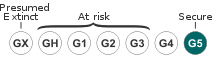

While not endangered or threatened, their main threat is human ignorance. Diamondback water snakes are often mistaken for cottonmouths or rattlesnakes and are killed out of fear. In actuality, diamondback water snakes (and other species of water snake) are far more common than the venomous snakes in their range, especially in areas that are frequented by humans.

In captivity

Due to how common the species is, the diamondback water snake is frequently found in captivity, though there is little market value for it in the pet trade. Captive specimens will often bite when captured but become fairly docile with regular handling. They may also defecate when handled, which has a particularly offensive smell, probably due to their diet of mostly fish. They eat quite well in captivity if fed primarily fish but must be supplemented with vitamin B1. Larger specimens will often consume rodents.

References

- ↑ Stejneger, L., and T. Barbour. 1917. A Check List of North American Amphibians and Reptiles. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 125 pp. (Natrix rhombifera, p. 95.)

- 1 2 Smith, H.M., and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1982. Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Golden Press. New York. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3. (Nerodia rhombifera, pp. 154-155.)

- ↑ Conant, R. 1975. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Houghton Mifflin. Boston. xviii + 429 pp. ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Natrix rhombifera rhombifera, p. 142, Figure 34 + Plate 21 + Map 104.)

- ↑ Conant, R. 2016. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin. Boston. ISBN 0-544-12997-0 (paperback). (Nerodia rhombifer, p. 419.)

- ↑ Nafis, Gary. "Alien Reptiles and Amphibians Introduced Into California". A Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. Retrieved 2000-2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nerodia rhombifer. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Nerodia rhombifer |

Further reading

- Cagle, F. R. 1937. Notes on Natrix rhombifera as observed at Reelfoot Lake. Journ. Tennessee Acad. Sci. 12 179-85.

- Clay, W. M. 1938. A new water snake of the genus Natrix from Mexico. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 27 251-55. (Natrix rhombifera blanchardi)

- Conant, R. 1953. Three new water snakes of the genus Natrix from Mexico. Natural History Miscellanea 126 1-9. (Natrix rhombifera werleri, p. 4.)

- Conant, R. and W. Bridges. 1939. What Snake Is That? A Field Guide to the Snakes of the United States East of the Rocky Mountains. D. Appleton-Century. New York and London. Frontispiece map + viii + 163 pp. + Plates A-C, 1-32. (Natrix rhombifera rhombifera, p. 96 + Plate 17, Figure 48.)

- Hallowell, E. 1852. Descriptions of new species of reptiles inhabiting North America. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia 6 177-82. (Tropidonotus rhombifer, p. 177.)

- Schmidt, K. P. and D. D. Davis. 1941. Field Book of Snakes of the United States and Canada. G.P. Putnam's Sons. New York. 365 pp. (Natrix rhombifera rhombifera, pp. 217-218, Figure 71. + Plate 23, Bottom, on p. 343.)

- Wright, A. H. and A. A. Wright. 1957. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock. Ithaca and London. 1,105 pp. (in 2 volumes) (Natrix rhombifera rhombifera, pp. 500-504, Figure 147, Map 41.)

External links

- Species Nerodia rhombifer at The Reptile Database

- Herps of Texas: Nerodia rhombifer

- Illinois Natural History Survey: Nerodia rhombifer

- Diamondback Watersnake, Nerodia rhombifer. Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide