Don L. Anderson

| Don L. Anderson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 5, 1933 Frederick, Maryland |

| Died |

December 2, 2014 (aged 81) Cambria, California |

| Residence | United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Seismology, Geophysics, Geology, Geochemistry |

| Institutions | California Institute of Technology, Caltech Seismological Laboratory |

| Alma mater | Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, California Institute of Technology |

| Doctoral advisor | Frank Press [1] |

| Doctoral students | Martin Smith, Lane Johnson, Bruce Julian, "Francis" Wu, "Leon" Teng, Charles G. Sammis, Harmuth Spetzler, Thomas H. Jordan, James Whitcomb, Hsi-Ping Liu, Scott David King, Jeffrey Given, Shingo Watada, Janice Regan, Eric Chael, Hua-Wei Zhou, Lianxing Wen.[2] |

| Known for | Plate Tectonics, Seismology, Geochemistry, Scientific Poetry |

| Notable awards |

|

| Notes | |

|

Anderson's expertise in numerous scientific disciplines has been recognized with gold medals from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Geological Society of America, the Royal Astronomical Society, and the highest science medals from the American Geophysical Union and the President of the United States. | |

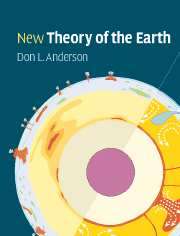

Don Lynn Anderson (March 5, 1933 – December 2, 2014) was an American geophysicist who made significant contributions to the understanding of the origin, evolution, structure, and composition of Earth and other planets. An expert in numerous scientific disciplines, Anderson’s work combined seismology, solid state physics, geochemistry and petrology to explain how the Earth works. Anderson was best known for his contributions to the understanding of the Earth’s deep interior, and more recently, for explaining that volcanoes are the product of plate tectonics rather than narrow plumes emanating from the deep Earth. Anderson was Professor (Emeritus) of Geophysics in the Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). He received numerous awards from geophysical, geological and astronomical societies. In 1998 he was awarded the prestigious Crafoord Prize by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences along with Adam Dziewonski.[3] Later that year, Anderson received the National Medal of Science. He held honorary doctorates from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (where he did his undergraduate work in geology and geophysics) and the University of Paris (Sorbonne), and served on numerous university advisory committees, including those at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, University of Chicago, Stanford, University of Paris, Purdue University, and Rice University. Anderson’s wide-ranging research resulted in hundreds of published papers in the fields of planetary science, seismology, mineral physics, petrology, geochemistry, tectonics and the philosophy of science. He continued to work and publish until his death. His widely known textbooks, Theory of the Earth, and New Theory of the Earth are regarded by colleagues as compelling syntheses of the origins of the Earth and its inner workings by one of the great geophysical authorities of our time.

Life and main scientific contributions

Born in Frederick, Maryland in 1933,[4] Anderson moved to Baltimore when he was six. He graduated from Baltimore Polytechnic Institute[5] then attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) where he earned a Bachelor of Science in geology and geophysics in 1955. He then worked in the oil industry in California, Montana and Wyoming, and served in the Air Force in Massachusetts and Thule, Greenland before moving to California, where he received a Ph.D. in geophysics and mathematics at Caltech in 1962. He spent most of his subsequent academic career at Caltech's Seismological Laboratory, becoming its second longest serving director from 1967 to 1989. He was married to Nancy Ruth Anderson, had two children, Lynn Anderson Rodriguez and Lee Weston Anderson, and four granddaughters.

Anderson began his scientific career while serving in the U.S. Air Force. In Greenland, he studied the properties of sea ice. Anderson was charged with determining whether the ice was strong enough to withstand the landing of heavy aircraft. In working with his colleague, Dr. Wilford Weeks, on scientific papers resulting from the research, it became clear to Anderson that he needed more education. He chose to attend Caltech in geophysics. Anderson’s thesis focused on the anisotropic, or directionally dependent, properties of the mantle. It analyzed wave propagation in layered complex media. Prior to Anderson’s work, seismologists had assumed that the Earth’s interior behaved like glass, and was isotropic. After completing his Ph.D. in 1962, Anderson joined the faculty at Caltech and moved on to other areas of study, writing papers on the composition, physical state, and origin of the Earth as well as other planets. Much later in his career, he returned to the effects of anisotropy and partial melting and the presence of fluids in the upper mantle. He and his colleagues developed methods for taking into account anisotropy and the non-elastic behavior of seismic waves to explain how the Earth works. The technical terms for the subjects of his studies are anharmonicity, asphericity, anelasticity, as well as anisotrophy. In other words, the Earth is not an ideal, elastic sphere.

During his more than 50-year career, Anderson published papers on the composition and origin of the Moon, Venus and Mars as well as Earth. He was a principal investigator on the Viking mission to Mars in 1971. Anderson and his collaborators investigated the relations between the behavior of mantle rock under high pressures and temperatures, phase transformations of mantle minerals, and the generation of earthquakes. They contributed significantly to the understanding of tectonic plate motions by mapping convection currents in the Earth's mantle using seismological methods. These studies led to the development of the Preliminary Reference Earth Model (PREM), which provides standard values for Earth's important properties, including seismic velocities, density, pressure, attenuation, and anisotropy as a function of planetary radius and wavelength. PREM is now the standard reference model for the Earth. This work was cited when Anderson, along with his colleague Adam Dziewonskiof Harvard University, were awarded the Crafoord Prize in 1998 in Sweden.

By taking into account the physics and thermodynamics of Earth materials under the high temperature and pressure conditions in the deep interior, Anderson developed theories that depart from mainstream scientific speculations. In particular, Anderson showed that the standard geochemical and evolutionary models for the Earth are flawed because they violate the laws of thermodynamics in ways that would make Earth behave as a perpetual motion machine. Anderson likened these models to Rudyard Kipling’s “Just-So Stories,” and pointed out that these flawed theories are perpetuated when counterveiling evidence is explained away as anomalies or paradoxes. Anderson’s models are based on physics and thermodynamics as well as geophysics, and stand up to observations and evidence-based tests.

Anderson developed an alternative model of the mineralogical and isotopic composition of the mantle. The Earth had a high-temperature origin and has been chemically stratified since it accreted 4.5 billion years ago. Conventional scientific wisdom is that the entire mantle is largely made up of olivine-dominated peridotite, some of it primordial material. Anderson, on the other hand, showed that the mid-mantle is composed of piclogite, a pyroxene and garnet-rick rock. Counter to prevailing scientific views, Anderson argued that the deeper layers of the mantle are dense and refractory and unable to rise to the surface or to produce basalts. Anderson suggested that all basalts are produced in the upper mantle. These ideas evolved from the integration of geochemistry, petrology, seismology, and thermodynamics, while standard models are based only on one or two of these disciplines and many assumptions.

Anderson also challenged traditional scientific views on how volcanoes are formed, particularly, the theory of convective mantle plumes in the Earth, as proposed by W. Jason Morgan, Anderson argued that the so-called mantle plume hypothesis is invalid and that hotspots and oceanic islands such as Hawaii or Iceland are, instead, the normal products of plate tectonics. While many geochemists believe that volcanoes stem from narrow plumes coming up from just above the Earth’s core, Anderson showed that they can be explained entirely by chemical and mineralogical anomalies in the upper mantle. Moreover, Anderson pointed out that all demonstrations of the mantle plume hypothesis violate the basic laws of thermodynamics because they rely on a constant supply of heat coming from the deep Earth or even from outside the Earth. Anderson, on the other hand, accepted the classical view that the Earth’s interior is cooling and that volcanoes simply tap a layer of melted rock that exists in the upper mantle, or outer shell of the Earth. It is through the movement of the plates that the magma is allowed to reach the surface through fracture zones, rifts, volcanoes and so-called hot spots. Anderson also considered that plate tectonics is a natural result of a planet being cooled from above.[6]

Although his work was based on seismology, classical physics and thermodynamics as well as his knowledge of the Earth’s interior, Anderson’s theories are considered to be controversial because they depart from the prevailing ideas developed by the geochemical community and which are widely cited in influential publications such as Nature and Science. An active website, mantleplumes.org, is devoted to the challenge by Anderson and his colleagues to standard, or text-book explanations of volcanoes and Earth dynamics. Anderson’s multidisciplinary approach, combined with his expertise in geophysics, geochemistry, solid-state physics, and thermodynamics, enabled him to explain the evolution and structure of the Earth in ways that challenge accepted ideas of his time. Colleague Seth Stein of Northwestern University said of Anderson’s New Theory of the Earth: “An old adage says that there are no true students of the Earth because we dig our small holes and sit in them. This book is a striking counter example that synthesizes a broad range of topics dealing with the planet’s structure, evolution, and dynamics. Even readers who disagree with some of the arguments will find them insightful and stimulating.”

Anderson died in Cambria, California on December 2, 2014 from cancer, at the age of 81.[4]

Technical details

- Showed that anisotropy and anelasticity were important in the propagation of seismic waves in the Earth.

- Introduced frequency dependent and polarization effects into modern seismology. This made it possible to resolve discrepancies between various types of seismic data (body waves, normal models; Rayleigh-Love wave discrepancy) and to combine all types of data into a single inversion.

- Developed theory for frequency dependence of both wavespeeds and anelasticity (Q) and applied this to the mantle and core (Absorption Band Model).

- Developed methods for inverting surface waves for anisotropic structures (Universal Dispersion Curves).

- Showed (with Minster) how microphysics could explain how short period phenomena could be related to long term rheology.

- With Nataf, Nakanishi, Tanimoto, Montagner, Regan developed first 3D structures of the anisotropic mantle.

Awards and honors

- James B. Macelwane Medal of the American Geophysical Union (1966)[7]

- Apollo Achievement Award of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration 1969

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1972)[8]

- Newcomb Cleveland Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1977) (Viking Mission Scientists) [9]

- NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal (1977)

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1982)

- Honorary Foreign Fellow of the European Union of Geosciences (1985)[10]

- Emil Wiechert Medal of the German Geophysical Society (1986)[11]

- Arthur L. Day Medal of the Geological Society of America (1987)[12]

- Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1988)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1988)[13]

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (1990) [14]

- William Bowie Medal of the American Geophysical Union (1991)[15]

- Guggenheim Fellow (1998)[16]

- Crafoord Prize of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science (1998 with Dziewonski)[3]

- National Medal of Science (1998)[17]

- Honorary doctorates from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) and University of Paris (Sorbonne)

Important publications

- A. M. Dziewonski; D. L. Anderson. (1981). Preliminary reference Earth model; Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 25, S.297–356.

- D. L. Anderson. (2007). New Theory of the Earth; Cambridge University Press, New York.

- D. L. Anderson. (1989). Theory of the Earth; Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- Don L. Anderson and James H. Natland. (2014) Mantle updrafts and mechanisms of oceanic volcanism; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences vol. 111 no. 41. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410229111.

- D. L. Anderson. (2013). The persistent mantle plume myth - Do plumes exist?; Australian Journal of Earth Sciences: and James H. Natland. doi:10.1080/08120099.2013.835283

- Anderson, Don L. (2011). Hawaii, Boundary Layers and Ambient Mantle - Geophysical Constraints, J. Petrol., 52, 1547-1577; doi:10.1093/petrology/egq068.

- G. R. Foulger, D. L. Anderson. (2005). A cool model for the Iceland hotspot; Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 141.

- Anderson, D. L. (2005). Self-gravity, self-consistency, and self-organization in geodynamics and geochemistry, in Earth's Deep Mantle: Structure, Composition, and Evolution, Eds. R.D. van der Hilst, J. Bass, J. Matas & J. Trampert, AGU Geophysical Monograph Series 160, 165-186.

- Anderson, D. L. (2005). Scoring hotspots: The plume and plate paradigms, in Foulger, G.R., Natland, J.H., Presnall, D.C., and Anderson, D.L., eds., Plates, plumes, and paradigms: Geological Society of America Special Paper 388, p. 31–54.

- Anderson, Don L. and Natland, J. H. (2005). A brief history of the plume hypothesis and its competitors: Concept and controversy, in Foulger, G.R., Natland, J.H., Presnall, D.C., and Anderson, D.L., eds., Plates, Plumes, & Paradigms, : GSA Special Paper 388, p. 119-145.

- Meibom, A. and Anderson, D. L. (2003). The Statistical Upper Mantle Assemblage, Earth Planet Science Letters, 217, pp. 123–139.

- Wen, L., and Anderson, Don L. (1997). Layered mantle convection: A model for geoid and topography, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 146, p. 367-377.

- Anderson, Don L. (1995). Lithosphere, asthenosphere and perisphere, Reviews of Geophysics, v. 33, p. 125-149.

- Anderson, Don L.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Tanimoto, T. (1992). Plume heads, continental lithosphere, flood basalts and tomography, in: Magmatism and the Causes of Continental Break-up, B. C. Storey, T. Alabaster and R. J. Pankhurst, eds., Geological Society Special Publication, No. 68.

- Anderson, Don L.; Tanimoto, T.; and Zhang,Y.-S. (1992). Plate tectonics and hotspots: The third dimension, Science, v. 256, p. 1645-1650.

- Scrivner, C. and Anderson, Don L. (1992). The effect of post Pangea subduction on global mantle tomography and convection, Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 19, no. 10, p. 1053-1056.

- Anderson, Don L. (1989). Where on Earth is the Crust?, Physics Today, March, p. 38-46.

- Anderson, Don L. (1987). A Seismic Equation of State II. Shear Properties and Thermodynamics of the Lower Mantle, Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors, v. 45, p. 307-323.

- Anderson, Don L. (1985). Hotspot magmas can form by fractionation and contamination of MORB, Nature, v. 318, p. 145-149.

- Tanimoto, T., and Anderson, Don L. (1985). Lateral heterogeneity and azimuthal anisotropy of the upper mantle: Love and Rayleigh waves 100-250 sec, Jour. Geophys. Res., v. 90, p. 1842-1858.

- Anderson, Don L. (1986). Earth sciences & public policy, Geotimes, v. 31, no. 10, p. 5.

- Nataf, H.-C.; Nakanishi, I.; and Anderson, Don L. (1986). Measurements of Mantle Wave Velocities and Inversion for Lateral Heterogeneities and Anisotropy, Part III: Inversion, Jour. Geophys. Res., v. 91, no. B7, p. 7261-7307.

- Anderson, Don L. (1984). The Earth as a planet: paradigms and paradoxes, Science, v. 223, no. 4634, p. 347-355. 178.

- Anderson, Don L. (1982). Hotspots, polar wander, mesozoic convection, and the geoid, Nature, v. 297, no. 5865, p. 391-393.

- Anderson, Don L.; and Given, J. W. (1982). Absorption band Q model for the Earth, Jour. Geophys. Res., v. 87, no. B5, p. 3893-3904.

See also

References

- ↑ http://thesis.library.caltech.edu/4076/

- ↑ http://thesis.library.caltech.edu/view/advisor/Anderson-D-L.html

- 1 2 "The Crafoord Prize 1998". Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- 1 2 Svitil, Kathy (3 December 2014). "Don L. Anderson 1933–2014". News & Events. Caltech. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ "Interview with Don L. Anderson" (PDF). Caltech Archives Oral Histories Online. California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Harding, Stephan. Animate Eart. Science, Intuition and Gaia. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2006, p. 114. ISBN 1-933392-29-0

- ↑ "James B. Macelwane Medal". American Geophysical Union. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "AAAS Newcomb Cleveland Prize". American Academy for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "EUG Honorary Fellows". European Union of Geoscientists. European Geosciences Union. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Emil-Wiechert-Medaille". Deutsche Geophysikalische Gesellschaft (in German). Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Past Award & Medal Recipients". Geological Society of America. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Winners of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society". Royal Astronomical Society. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Public Profile: Dr. Don L. Anderson". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "William Bowie Medal". American Geophysical Union. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Don L. Anderson: Search Results". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "The Laureates 1998". National Science & Technology Medals Foundation. Retrieved 18 April 2011.