Dorothy Hodgkin

| Dorothy Hodgkin | |

|---|---|

|

Dorothy Hodgkin | |

| Born |

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot 12 May 1910 Cairo, Egypt |

| Died |

29 July 1994 (aged 84) Ilmington, Warwickshire, England |

| Residence | England |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Biochemistry, X-ray crystallography |

| Alma mater | |

| Doctoral advisor | John Desmond Bernal |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students |

|

| Known for |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (m. 1937) |

| Children | Luke, Elizabeth, and Toby |

Dorothy Mary Hodgkin OM FRS[2] (12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994), known professionally as Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin or simply Dorothy Hodgkin, was a British biochemist who developed protein crystallography, for which she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964.[2][4][5][6][7][8][9]

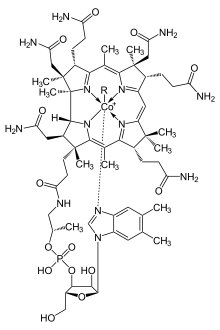

She advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography, a method used to determine the three-dimensional structures of biomolecules. Among her most influential discoveries are the confirmation of the structure of penicillin that Ernst Boris Chain and Edward Abraham had previously surmised, and then the structure of vitamin B12, for which she became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[9]

In 1969, after 35 years of work and five years after winning the Nobel Prize, Hodgkin was able to decipher the structure of insulin. X-ray crystallography became a widely used tool and was critical in later determining the structures of many biological molecules where knowledge of structure is critical to an understanding of function. She is regarded as one of the pioneer scientists in the field of X-ray crystallography studies of biomolecules.

Early life

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot was born in Cairo, Egypt, to John Winter Crowfoot (1873–1959), an archaeologist and classical scholar, and Grace Mary Crowfoot née Hood (1877–1957), an archaeologist and expert on Ancient Egyptian textiles. She lived in the English expatriate community in Egypt, returning to England only a few months each year. During one of those stays in England, when Hodgkin was four, World War I began. Her mother lost four brothers in the war.[10] Separated from her parents, who would return to Egypt, she was left under the care of relatives and friends until after the end of the war when her mother came to England for one year, a period that she later described as the happiest in her life.

In 1921, she entered the Sir John Leman Grammar School in Beccles. Only once, when she was 13, did she make an extended visit to her parents, who by then had moved to Khartoum, although both parents continued to visit England each summer.

Education and research

She developed a passion for chemistry from a young age, and her mother fostered her interest in science in general. Her state school education left her without Latin or a further science subject, but she took private tuition in order to enter the University of Oxford entrance examination. At the age of 18 she started studying Chemistry at the University of Oxford (Somerville College).[11] In 1932 Hodgkin was awarded a first-class honours degree at the University of Oxford – as the third woman ever to achieve this.[12]

She studied for a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge supervised by John Desmond Bernal,[13] where she became aware of the potential of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of proteins, working with him on the technique's first application to the analysis of a biological substance, pepsin.[14] The pepsin experiment is largely credited to Hodgkin herself, but Hodgkin always made it clear that it was Bernal who initially took the photographs and had given her additional key insights[15]

In 1933 she was awarded a research fellowship by Somerville College, and in 1934, she moved back to Oxford. The college appointed her its first fellow and tutor in chemistry in 1936, a post which she held until 1977. In the 1940s, one of her students was Margaret Roberts, the future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher,[16] who installed a portrait of Hodgkin in Downing Street in the 1980s.[11]

Together with Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton, she was one of the first people in April 1953 to travel from Oxford to Cambridge to see the model of the double helix structure of DNA, constructed by Francis Crick and James Watson, based on data and technique acquired by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. According to the late Dr. Beryl Oughton, later Rimmer, they all travelled together in two cars once Dorothy Hodgkin announced to them that they were off to Cambridge to see the model of the structure of DNA.

In 1960, she was appointed the Royal Society's Wolfson Research Professor, a position she held until 1970.[9] This provided her salary, research expenses and research assistance to continue her work at the University of Oxford.

Discoveries

.jpg)

Hodgkin was particularly noted for discovering three-dimensional biomolecular structures.[4] In 1945, working with C. H. (Harry) Carlisle, she published the first such structure of a steroid, cholesteryl iodide (having worked with cholesteryls since the days of her doctoral studies).[17] In 1945, she and her colleagues solved the structure of penicillin, demonstrating (contrary to scientific opinion at the time) that it contains a β-lactam ring. However, the work was not published until 1949.[18]

In 1948, Hodgkin first encountered vitamin B12,[19] and created new crystals. Vitamin B12 had first been discovered by Merck earlier that year. It had a structure at the time that was almost completely unknown, and when Hodgkin discovered it contained cobalt, she realized the structure actualization may be determined by x-ray crystallography analysis. The large size of the molecule, and that the atoms were largely unaccounted for – aside from cobalt - posed a challenge in structure analysis that hadn't been previously explored.[20] From these crystals, she deduced the presence of a ring structure because the crystals were pleochroic, a finding which she later confirmed using X-ray crystallography. The B12 study published by Hodgkin was described by Lawrence Bragg as being as significant "as breaking the sound barrier".[20][21] Scientists from Merck had previously crystallised B12, but had published only refractive indices of the substance.[22] The final structure of B12, for which Hodgkin was later awarded the Nobel Prize, was published in 1955.[23]

Insulin structure

Insulin was one of her most extraordinary research projects. It began in 1934 when she was offered a small sample of crystalline insulin by Robert Robinson. The hormone captured her imagination because of the intricate and wide-ranging effect it has in the body. However, at this stage X-ray crystallography had not been developed far enough to cope with the complexity of the insulin molecule. She and others spent many years improving the technique. Larger and more complex molecules were being tackled until in 1969 – 35 years later – the structure of insulin was finally resolved.[24] But her quest was not finished then. She cooperated with other laboratories active in insulin research, gave advice, and travelled the world giving talks about insulin and its importance for diabetes.

Social and personal life

Hodgkin's scientific mentor Professor John Desmond Bernal greatly influenced her life both scientifically and politically. He was a distinguished scientist of great repute in the scientific world, a member of the Communist Party, and a faithful supporter of successive Soviet regimes until their invasion of Hungary. She always referred to him as "Sage"; intermittently, they were lovers. The conventional marriages of both Bernal and Hodgkin were far from smooth.[25]

In 1937, Dorothy married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, then recently returned from working for the Colonial Office and moving into adult education.[26] He later became a well-known Oxford lecturer, the author of several major works on African history and politics and an occasional member of the Communist Party.[27] In 1961 Thomas became an advisor to Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, in whose country he remained for extended periods, and where she often visited him. Because of her political activity, and her husband's association with the Communist Party, she was banned from entering the US in 1953 and subsequently not allowed to visit the country except by CIA waiver.[28]

The couple had three children: Luke[29] (born 1938), Elizabeth[30] (born 1941) and Toby[31] (born 1946).

At the age of 24, Hodgkin began experiencing pain in her hands. A visit to a doctor led to a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis which would become progressively worse and crippling over time with deformities in both her hands and feet. Eventually, Hodgkin spent a great deal of time in a wheelchair but remained scientifically active despite her disability.[32]

Hodgkin was also concerned about social inequalities and stopping conflict. As a consequence she was president of Pugwash from 1976 to 1988.[33] However, Hodgkin retains some infamy for having written the foreword to the 1983 English edition of Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene, which carried the authorship of Elena Ceausescu, the wife of the communist dictator of Romania at the time. In the foreword, Hodgkin speaks glowingly of Ceausescu's "outstanding achievements" and "impressive" career.[34] After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, it was widely revealed that Ceausescu never finished secondary school, never attended university, that her scientific credentials were a hoax, and the publication in question – like all the research published under her name throughout her life – was written by a team of scientists in her name in order to obtain a fraudulent doctorate to advance her international prestige as a communist political figure.[35]

On 29 July 1994, Hodgkin died after a stroke at her home in Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire.[9]

Names

Hodgkin published as "Dorothy Crowfoot" until 1949, when she was persuaded by Hans Clarke’s secretary to use her married name on her chapter in The Chemistry of Penicillin. Thereafter she always published using the name "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin", the name used by the Nobel Foundation in its biographies of Nobel Prize recipients[36] and by the Chemical Heritage Foundation.[37] Hodgkin is referred to simply as "Dorothy Hodgkin" by institutions including The Royal Society, sponsor of the Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship,[38] while The National Archives of the United Kingdom names her "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin".

Honours, awards and legacy

Hodgkin won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1964. She was the second woman to receive the Order of Merit in 1965; preceded only by Florence Nightingale. The first, and as of 2016, the only woman to receive the Copley Medal. She was a winner of the Lenin Peace Prize.

Hodgkin was Chancellor of the University of Bristol from 1970 to 1988. She was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1947[2] and an EMBO Member in 1970.[3] She was awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) from the University of Bath in 1978.[39] In 1958, she was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[40]

In 1983, Hodgkin received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.[41] In 1966, she was awarded the Iota Sigma Pi National Honorary Member for her significant contribution.[42]

The Royal Society has established the Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship for early career stage researchers.[38]

Hodgkin was one of five 'Women of Achievement' selected for a set of British stamps issued in August 1996. The others were Marea Hartman (sports administrator), Margot Fonteyn (ballerina/choreographer), Elisabeth Frink (sculptor) & Daphne du Maurier (writer). All except Hodgkin were Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBEs).

In 2010, during its 350th anniversary, the Royal Society celebrated with the publication of 10 stamps of some of its most illustrious members, bestowing Professor Hodgkin with her second stamp. She was in the company of nine men: Isaac Newton, Edward Jenner, Joseph Lister, Benjamin Franklin, Charles Babbage, Robert Boyle, Ernest Rutherford, Nicholas Shackleton and Alfred Russel Wallace.[43]

Council offices in the London Borough of Hackney and buildings at King's College London, University of York, Bristol University and Keele University are named after her, as is the science block at Sir John Leman High School, her former school.

In 2012, Hodgkin featured in the BBC Radio 4 series The New Elizabethans to mark the diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. A panel of seven academics, journalists and historians named her among the group of people in the UK "whose actions during the reign of Elizabeth II have had a significant impact on lives in these islands and given the age its character".[44]

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin's 1949 paper entitled "The X-ray Crystallographic Investigation of the Structure of Penicillin" published with colleagues C. W. Bunn, B. W. Rogers-Low, and A. Turner Jones[45] was honoured by a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society presented to the University of Oxford (England) in 2015. This research is notable for its groundbreaking use of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of complex natural products, in this instance, of penicillin.[46][47] Hodgkin used her maiden name "D. Crowfoot" in this paper published many years after her marriage.[45]

Dorothy Hodgkin Memorial Lecture

Since 1999, the Royal Society of Chemistry has presented an annual memorial lecture, every March, in honour of Hodgkin's work.

- Professor Louise Johnson, "Dorothy Hodgkin and penicillin", 4 March 1999.

- Professor Judith Howard, "The Interface of Chemistry and Biology Increasingly in Focus", *13 March 2000.

- Professor Jenny Glusker, "Vitamin B12 and Dorothy: Their impact on structural science", 15 May 2001.

- Professor Pauline Harrison CBE, "From Crystallography to Metals, Metabolism and Medicine", 5 March 2002.

- Dr Claire Naylor, "Pathogenic Proteins: how bacterial agents cause disease", 4 March 2003.

- Dr Margaret Adams, "A Piece in the Jigsaw: G6PD – The protein behind an hereditary disease", 9 March 2004.

- Dr. Margaret Rayman, "Selenium in cancer prevention", 10 March 2005.

- Dr Elena Conti, "Making sense of nonsense: structural studies of RNA degradation and disease", 9 March 2006.

- Professor Jenny Martin, "The name's Bond – Disulphide Bond", 6 March 2007.

- Professor E. Yvonne Jones, "Postcards from the surface: The Structural Biology of Cell-Cell Communication", 4 March 2008.

- Professor Pamela J. Bjorkman, "Your mother's antibodies: How you get them and how we might improve them to combat HIV", 11 March 2009.

- Professor Elspeth Garman, "Crystallography 100 years A.D (After Dorothy)" 9 March 2010.

- Professor Eleanor Dodson, "Mathematics in the service of Crystallography" 10 March 2011.

- Professor Sir Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, "How antibiotics illuminate ribosome function and vice versa" March 2012.

- Professor Susan Lea, "Bacterial secretion systems – using structure to build towards new therapeutic opportunities", 5 March 2013.

- Professor Carol V. Robinson, "Finding the Right Balance", 11 March 2014

- Professor Petra Fromme, 12 March 2015

- Professor Dame Kay Davies CBE FRS FMedSci, "Therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the genomic era" 4 March 2016

References

- ↑ Blundell, T.; Cutfield, J.; Cutfield, S.; Dodson, E.; Dodson, G.; Hodgkin, D.; Mercola, D.; Vijayan, M. (1971). "Atomic positions in rhombohedral 2-zinc insulin crystals". Nature. 231 (5304): 506–511. Bibcode:1971Natur.231..506B. doi:10.1038/231506a0. PMID 4932997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 - 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. London: Royal Society. 48 (0): 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606.

- 1 2 Anon (2014). "EMBO profile Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". people.embo.org. Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Organization.

- 1 2 Glusker, J. P. (1994). "Dorothy crowfoot hodgkin (1910-1994)". Protein Science. 3 (12): 2465–2469. doi:10.1002/pro.5560031233. PMC 2142778

. PMID 7757003.

. PMID 7757003. - ↑ Glusker, J. P.; Adams, M. J. (1995). "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Physics Today. 48 (5): 80. Bibcode:1995PhT....48e..80G. doi:10.1063/1.2808036.

- ↑ Johnson, L. N.; Phillips, D. (1994). "Professor Dorothy Hodgkin, OM, FRS". Nature Structural Biology. 1 (9): 573–576. doi:10.1038/nsb0994-573. PMID 7634095.

- ↑ Perutz, Max (1994). "Obituary: Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-94)". Nature. 371 (6492): 20–20. Bibcode:1994Natur.371...20P. doi:10.1038/371020a0. PMID 7980814.

- ↑ Perutz, M. (2009). "Professor Dorothy Hodgkin". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 27 (4): 333–337. doi:10.1017/S0033583500003085. PMID 7784539.

- 1 2 3 4 Anon (2014). "The Biography of Dorothy Mary Hodgkin". news.biharprabha.com. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ↑ "Dorothy Hodgkin 1910 - 1994". A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries a 1997 PBS documentary and accompanying book.

- 1 2 Ferry, Georgina (1999). Dorothy Hodgkin : a life. London: Granta Books. ISBN 186207285X.

- ↑ "Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Encyclopedia.com. Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Hodgkin, D. M. C. (1980). "John Desmond Bernal. 10 May 1901-15 September 1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 26: 16. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1980.0002.

- ↑ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, OM". Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ↑ Dodson, Guy (1 December 2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M.". Biographical Memoirs. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011.

- ↑ Young, Hugo (1989). One of us: a biography of Margaret Thatcher. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-34439-1.

- ↑ Carlisle, C. H.; Crowfoot, D. (1945). "The Crystal Structure of Cholesteryl Iodide". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 184 (996): 64. Bibcode:1945RSPSA.184...64C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1943.0040.

- ↑ Crowfoot, D.; Bunn, Charles W.; Rogers-Low, Barbara W.; Turner-Jones, Annette (1949). "X-ray crystallographic investigation of the structure of penicillin". In Clarke, H. T.; Johnson, J. R.; Robinson, R. Chemistry of Penicillin. Princeton University Press. pp. 310–367.

- ↑ Hodgkin, Dorothy. "Beginning to work on vitamin B12". Web of Stories. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Tools Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Encyclopedia.com. Cengage Learning. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Brink, C.; Hodgkin, D. C.; Lindsey, J.; Pickworth, J.; Robertson, J. H.; White, J. G. (1954). "Structure of Vitamin B12: X-ray Crystallographic Evidence on the Structure of Vitamin B12". Nature. 174 (4443): 1169–71. Bibcode:1954Natur.174.1169B. doi:10.1038/1741169a0. PMID 13223773.

- ↑ RICKES, E. L.; BRINK, N. G.; KONIUSZY, F. R.; WOOD, T. R.; FOLKERS, K. (16 April 1948). "Crystalline Vitamin B12". Science. 107 (2781): 396–397. Bibcode:1948Sci...107..396R. doi:10.1126/science.107.2781.396. PMID 17783930.

- ↑ Hodgkin, D. C.; Pickworth, J.; Robertson, J. H.; Trueblood, K. N.; Prosen, R. J.; White, J. G. (1955). "Structure of Vitamin B12 : The Crystal Structure of the Hexacarboxylic Acid derived from B12 and the Molecular Structure of the Vitamin". Nature. 176 (4477): 325–8. Bibcode:1955Natur.176..325H. doi:10.1038/176325a0. PMID 13253565.

- ↑ Adams, M. J.; Blundell, T. L.; Dodson, E. J.; Dodson, G. G.; Vijayan, M.; Baker, E. N.; Harding, M. M.; Hodgkin, D. C.; Rimmer, B.; Sheat, S. (1969). "Structure of Rhombohedral 2 Zinc Insulin Crystals". Nature. 224 (5218): 491. Bibcode:1969Natur.224..491A. doi:10.1038/224491a0.

- ↑ Ferry, Georgina (1998). Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life. London: Granta Books. ISBN 1-86207-167-5.

- ↑ "Mr Thomas Hodgkin". The Times. 26 March 1982.

- ↑ Michael Wolfers, ‘Hodgkin, Thomas Lionel (1910–1982)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008, accessed 15 January 2010

- ↑ Rose, Hilary (1994). Love, Power, and Knowledge: Towards a Feminist Transformation of the Sciences. Indiana University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780253209078.

- ↑ http://www.kcl.ac.uk/nms/depts/mathematics/people/atoz/hodgkinl.aspx

- ↑ http://riftvalley.net/directors-governance

- ↑ http://agrobiodiversityplatform.org/database/expert/toby-hodgkin/

- ↑ Walters, Kirsten. "Not Standing Still's Disease". Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ Howard, J. A. K. (2003). "Timeline: Dorothy Hodgkin and her contributions to biochemistry". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 4 (11): 891–896. doi:10.1038/nrm1243. PMID 14625538.

- ↑ Ceausescu, Elena (1983). Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene. Pergamon. ISBN 978-0-08-029987-7.

- ↑ Behr, Edward (1991). Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite. ISBN 0-679-40128-8.

- ↑ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin - Biographical". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ↑ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Chemical Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- 1 2 "Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship". Royal Society. 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "Honorary Graduates 1989 to present | University of Bath". Bath.ac.uk. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter H" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 690. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ "PROFESSIONAL AWARDS". Iota Stigma Pi: National Honor Society for Women in Chemistry. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "Getting the Royal Society stamp of approval". New Scientist. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "The New Elizabethans - Dorothy Hodgkin". BBC. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- 1 2 D. Crowfoot, C. W. Bunn, B. W. Rogers-Low, A. Turner Jones, "The X-ray Crystallographic Investigation of the Structure of Penicillin," in H.T. Clarke, J.R. Johnson, R. Robinson (eds), The Chemistry of Penicillin, Princeton University Press, Chapter XI, pp. 310-366, 1949.

- ↑ "2015 Awardees". American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award" (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

Further reading

- Papers of Dorothy Hodgkin at the Bodleian Library. Catalogues at and .

- Ferry, Georgina (1998). Dorothy Hodgkin A Life. London: Granta Books.

- Dodson, Guy; Glusker, Jenny P.; Sayre, David (eds.) (1981). Structural Studies on Molecules of Biological Interest: A Volume in Honour of Professor Dorothy Hodgkin. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Glusker, Jenny P. in Out of the Shadows – Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics.

- Wolfers, Michael (2007). Thomas Hodgkin – Wandering Scholar: A Biography. Monmouth: Merlin Press.

- Hudson, Gill (1991). "Unfathering the Thinkable: Gender, Science and Pacificism in the 1930s". Science and Sensibility: Gender and Scientific Enquiry, 1780–1945, ed. Marina Benjamin, 264–286. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Royal Society of Edinburgh obituary

- Opfell, Olga S. (1978). Lady Laureates : Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize. Metuchen, N.J & London: Scarecrow Press. pp. 209–223. ISBN 0810811618.

- Dorothy Hodgkin tells her life story at Web of Stories (video)

- CWP – Dorothy Hodgkin in a study of contributions of women to physics

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin: A Founder of Protein Crystallography

- Nobel Prize 1964 page

- DorothyHodgkin.com

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dorothy Hodgkin |

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Duke of Beaufort |

Chancellor of the University of Bristol 1970–1988 |

Succeeded by Sir Jeremy Morse |