Dorothy L. Sayers

| Dorothy L. Sayers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

13 June 1893 Oxford, UK |

| Died |

17 December 1957 (aged 64) Witham, Essex, UK |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, essayist, translator, copywriter, poet |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | English |

| Genre | Crime fiction |

| Literary movement | Golden Age of Detective Fiction |

| Spouse |

Mac Fleming (m. 1926–50, his death) |

| Children | John Anthony Fleming (1924–1984) |

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (/ˈsɛərz/ SAIRZ;[1] 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was a renowned English crime writer, poet, playwright, essayist, translator, and Christian humanist. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between the First and Second World Wars that feature English aristocrat and amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey, which remain popular to this day. However, Sayers herself considered her translation of Dante's Divine Comedy to be her best work. She is also known for her plays, literary criticism, and essays.

Biography

Childhood, youth, and education

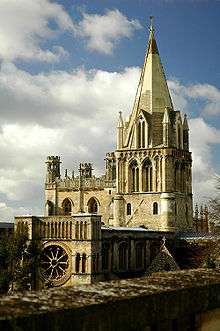

Sayers was an only child, born on 13 June 1893 at the Head Master's House, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. Her father, the Rev. Henry Sayers, M.A., was a chaplain of Christ Church and headmaster of the Choir School. When she was six, he started teaching her Latin.[2] She grew up in the tiny village of Bluntisham-cum-Earith in Huntingdonshire after her father was given the living there as rector. The church graveyard next to the elegant Regency rectory features the surnames of several characters from her mystery The Nine Tailors, and the nearby River Great Ouse and the Fens invite comparison with the book's vivid description of a massive flood around the village.[3]

From 1909 she was educated at the Godolphin School,[4] a boarding school in Salisbury. Her father later moved to the simpler living of Christchurch, in Cambridgeshire.

In 1912, Sayers won a scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford[5] where she studied modern languages and medieval literature. She finished with first-class honours in 1915.[6] Women could not be awarded degrees at that time, but Sayers was among the first to receive a degree when the position changed a few years later; in 1920 she graduated as an MA. Her experience of Oxford academic life eventually inspired her penultimate Peter Wimsey novel, Gaudy Night.

Her father was from Littlehampton, West Sussex, and her mother (Helen Mary Leigh – hence Sayers's second name) was born at "The Chestnuts", Millbrook, Hampshire, to Frederick Leigh, a solicitor whose family roots were in the Isle of Wight. Sayers's Aunt Amy, her mother's sister, married Henry Richard Shrimpton.

Career

Poetry, teaching, and advertisements

Sayers's first book of poetry was published in 1916 as OP. I [7] by Blackwell Publishing in Oxford. Her second book of poems, "Catholic Tales and Christian Songs", was published in 1918, also by Blackwell. Later, Sayers worked for Blackwell's and then as a teacher in several locations, including Normandy, France.

Sayers' longest employment was from 1922 to 1931 as a copywriter at S.H. Benson's advertising agency, located at International Buildings, Kingsway, London. Sayers was quite successful as an advertiser. Her collaboration with artist John Gilroy resulted in "The Mustard Club" for Colman's Mustard and the Guinness "Zoo" advertisements, variations of which still appear today. One famous example was the Toucan, his bill arching under a glass of Guinness, with Sayers's jingle:

If he can say as you can

Guinness is good for you

How grand to be a Toucan

Just think what Toucan do

Sayers is also credited with coining the slogan "It pays to advertise!"[8][9] She used the advertising industry as the setting of Murder Must Advertise, where she describes the role of truth in advertising:

... the firm of Pym's Publicity, Ltd., Advertising Agents ..."Now, Mr. Pym is a man of rigid morality—except, of course, as regards his profession, whose essence is to tell plausible lies for money—"

"How about truth in advertising?"

"Of course, there is some truth in advertising. There's yeast in bread, but you can't make bread with yeast alone. Truth in advertising ... is like leaven, which a woman hid in three measures of meal. It provides a suitable quantity of gas, with which to blow out a mass of crude misrepresentation into a form that the public can swallow."[8]

Detective fiction

Sayers began working out the plot of her first novel some time in 1920–21. The seeds of the plot for Whose Body? can be seen in a letter that Sayers wrote on 22 January 1921:

My detective story begins brightly, with a fat lady found dead in her bath with nothing on but her pince-nez. Now why did she wear pince-nez in her bath? If you can guess, you will be in a position to lay hands upon the murderer, but he's a very cool and cunning fellow ... (p. 101, Reynolds)

Lord Peter Wimsey burst upon the world of detective fiction with an explosive "Oh, damn!" and continued to engage readers in eleven novels and two sets of short stories, the final novel ending with a very different "Oh, damn!". Sayers once commented that Lord Peter was a mixture of Fred Astaire and Bertie Wooster, which is most evident in the first five novels. However, it is evident through Lord Peter's development as a rounded character that he existed in Sayers's mind as a living, breathing, fully human being.

Sayers introduced the character of detective novelist Harriet Vane in Strong Poison. She remarked more than once that she had developed the "husky voiced, dark-eyed" Harriet to put an end to Lord Peter via matrimony. But in the course of writing Gaudy Night, Sayers imbued Lord Peter and Harriet with so much life that she was never able, as she put it, to "see Lord Peter exit the stage".

Sayers did not content herself with writing pure detective stories; she explored the difficulties of First World War veterans in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, discussed the ethics of advertising in Murder Must Advertise, and advocated women's education (then a controversial subject) and role in society in Gaudy Night. In Gaudy Night, Miss Barton writes a book attacking the Nazi doctrine of Kinder, Kirche, Küche, which restricted women's roles to family activities, and in many ways the whole of Gaudy Night can be read as an attack on Nazi social doctrine. The book has been described as "the first feminist mystery novel."[10]

Sayers's Christian and academic interests are also apparent in her detective series. In The Nine Tailors, one of her most well-known detective novels, the plot unfolds largely in and around an old church dating back to the Middle Ages. Change ringing of bells also forms an important part of the novel. In Have His Carcase, the Playfair cipher and the principles of cryptanalysis are explained. Her short story Absolutely Elsewhere refers to the fact that (in the language of modern physics) the only perfect alibi for a crime is to be outside its light cone, while The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager's Will contains a literary crossword puzzle.

Sayers also wrote a number of short stories about Montague Egg, a wine salesman who solves mysteries.

Translations

Sayers herself considered her translation of Dante's Divine Comedy to be her best work. The boldly titled Hell appeared in 1949, as one of the recently introduced series of Penguin Classics. Purgatory followed in 1955. The third volume (Paradise) was unfinished at her death, and was completed by Barbara Reynolds in 1962.

On a line-by-line basis, Sayers's translation can seem idiosyncratic. For example, the famous line usually rendered "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here" turns, in the Sayers translation, into "Lay down all hope, you who go in by me." The Italian reads "Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate", and both the traditional rendering and Sayers' translation add to the source text in an effort to preserve the original length: "here" is added in the traditional, and "by me" in Sayers. Also, the addition of "by me" draws from the previous lines of the canto: "Per me si va ne la città dolente;/ per me si va ne l'etterno dolore;/ per me si va tra la perduta gente." (Longfellow: "Through me the way is to the city dolent;/ through me the way is to the eternal dole;/ through me the way is to the people lost.")

The idiosyncratic character of Sayers's translation results from her decision to preserve the original Italian terza rima rhyme scheme, so that her "go in by me" rhymes with "made to be" two lines earlier, and "unsearchably" two lines before that. Umberto Eco in his book Mouse or Rat? suggests that, of the various English translations, Sayers "does the best in at least partially preserving the hendecasyllables and the rhyme."[11]

Sayers's translation of the Divine Comedy is also notable for extensive notes at the end of each canto, explaining the theological meaning of what she calls "a great Christian allegory."[12] Her translation has remained popular: in spite of publishing new translations by Mark Musa and Robin Kirkpatrick, as of 2009 Penguin Books was still publishing the Sayers edition.[13]

In the introduction to her translation of The Song of Roland, Sayers expressed an outspoken feeling of attraction and love for:

"... That new-washed world of clear sun and glittering colour which we call the Middle Age (as though it were middle-aged) but which has perhaps a better right than the blown rose of the Renaissance to be called the Age of Re-birth".

She praised "Roland" for being a purely Christian myth, in contrast to such epics as Beowulf in which she found a strong pagan content.

Other Christian and academic work

Sayers's most notable religious book is probably The Mind of the Maker (1941) which explores at length the analogy between a human creator (especially a writer of novels and plays) and the doctrine of The Trinity in creation. She suggests that any human creation of significance involves the Idea, the Energy (roughly: the process of writing and that actual 'incarnation' as a material object), and the Power (roughly: the process of reading and hearing and the effect that it has on the audience). She draws analogies between this "trinity" and the theological Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

In addition to the ingenious thinking in working out this analogy, the book contains striking examples drawn from her own experiences as a writer, as well as elegant criticisms of writers who exhibit, in her view, an inadequate balance of Idea, Energy, and Power.[14] She strongly defends the view that literary creatures have a nature of their own, vehemently replying to a well-wisher who wanted Lord Peter to "end up a convinced Christian". "From what I know of him, nothing is more unlikely ... Peter is not the Ideal Man".[15]

Creed or Chaos? is a restatement of basic historical Christian Doctrine, based on the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed, similar to but somewhat more densely written than C.S. Lewis' Mere Christianity. Both sought to explain the central doctrines of Christianity, clearly and concisely, to those who had encountered them in distorted or watered-down forms, on the grounds that, if you are going to criticize something, you had best know what it is first.

Her very influential essay The Lost Tools of Learning[16] has been used by many schools in the US as a basis for the classical education movement, reviving the medieval trivium subjects (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) as tools to enable the analysis and mastery of every other subject. Sayers also wrote three volumes of commentaries about Dante, religious essays, and several plays, of which The Man Born to be King may be the best known.

Her religious works did so well at presenting the orthodox Anglican position that, in 1943, the Archbishop of Canterbury offered her a Lambeth doctorate in divinity, which she declined. In 1950, however, she accepted an honorary doctorate of letters from the University of Durham.

Her economic and political ideas are rooted in the classical Christian doctrines of Creation and Incarnation, and are very close to the Chesterton–Belloc theory of Distributism[17] – although she never describes herself as a Distributist.

Criticism of Sayers

Criticism of background material in her novels

The literary and academic themes in Sayers's novels have appealed to a great many readers, but by no means to all. Poet W. H. Auden and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein were critics of her novels, for example.[18][19] A savage attack on Sayers's writing ability came from the prominent American critic and man of letters Edmund Wilson, in a well-known 1945 article in The New Yorker called Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?[20] He briefly writes about her famous novel The Nine Tailors, saying "I set out to read [it] in the hope of tasting some novel excitement, and I declare that it seems to me one of the dullest books I have ever encountered in any field. The first part is all about bell-ringing as it is practised in English churches and contains a lot of information of the kind that you might expect to find in an encyclopedia article on campanology. I skipped a good deal of this, and found myself skipping, also, a large section of the conversations between conventional English village characters ..." Wilson continues "I had often heard people say that Dorothy Sayers wrote well ... but, really, she does not write very well: it is simply that she is more consciously literary than most of the other detective-story writers and that she thus attracts attention in a field which is mostly on a sub-literary level."

Academic critic Q.D. Leavis criticises Sayers in more specific terms, in a review of Gaudy Night and Busman's Honeymoon published in the critical journal Scrutiny. The basis of Leavis' criticism is that Sayers' fiction is "popular and romantic while pretending to realism."[21] Leavis argues that Sayers presents academic life as "sound and sincere because it is scholarly", a place of "invulnerable standards of taste charging the charmed atmosphere".[22] But, Leavis says, this is unrealistic: "If such a world ever existed, and I should be surprised to hear as much, it does no longer, and to give substance to a lie or to perpetrate a dead myth is to do no one any service really."[23] Leavis suggests that "people in the academic world who earn their livings by scholarly specialities are not as a general thing wiser, better, finer, decenter or in any way more estimable than those of the same social class outside", but that Sayers is popular among educated readers because "the accepted pretence is that things are as Miss Sayers relates". Leavis comments that "only best-seller novelists could have such illusions about human nature".[23]

Critic Sean Latham has defended Sayers, arguing that Wilson "chooses arrogant condescension over serious critical consideration", and suggesting that both he and Leavis, rather than seriously assessing Sayers' writing, simply objected to a detective story writer having pretensions beyond what they saw as her role of popular culture "hack".[18] Latham claims that, in their eyes, "Sayers's primary crime lay in her attempt to transform the detective novel into something other than an ephemeral bit of popular culture".[18]

Criticism of major characters

Lord Peter Wimsey, Sayers' heroic detective, has been criticized for being too perfect; over time, the various talents that he displays grow too numerous for some readers to swallow. Edmund Wilson also expressed his distaste for Lord Peter in his criticism of The Nine Tailors: "There was also a dreadful stock English nobleman of the casual and debonair kind, with the embarrassing name of Lord Peter Wimsey, and, although he was the focal character in the novel ... I had to skip a good deal of him, too."[20]

Wimsey is rich, well-educated, charming, and brave, as well as an accomplished musician, an exceptional athlete, and a notable lover. He does, however, have serious flaws: the habit of over-engaging in what other characters regard as silly prattling, a nervous disorder (shell-shock), and a fear of responsibility. The latter two both originate from his service in the First World War. The fear of responsibility turns out to be a serious obstacle to his maturation into full adulthood (a fact not lost on the character himself).

The character Harriet Vane, featured in four novels, has been criticized for being a mere stand-in for the author. Many of the themes and settings of Sayers's novels, particularly those involving Harriet Vane, seem to reflect Sayers's own concerns and experiences.[24] Vane, like Sayers, was educated at Oxford (unusual for a woman at the time) and is a mystery writer. Vane initially meets Wimsey when she is tried for poisoning her lover (Strong Poison); he insists on participating in the defence preparations for her re-trial, where he falls for her but she rejects him. In Have His Carcase, she collaborates with Wimsey to solve a murder but still rejects his proposals of marriage. She eventually accepts (Gaudy Night) and marries him (Busman's Honeymoon).

Alleged anti-Semitism in Sayers's writing

Biographers of Sayers have disagreed as to whether Sayers was anti-Semitic. In Sayers: A Biography,[25] James Brabazon argues that she was. This is rebutted by Carolyn G. Heilbrun in Dorothy L. Sayers: Biography Between the Lines.[26] McGregor and Lewis argue in Conundrums for the Long Week-End that Sayers was not anti-Semitic but used popular British stereotypes of class and ethnicity. In 1936, a translator wanted "to soften the thrusts against the Jews" in Whose Body?; Sayers, surprised, replied that the only characters "treated in a favourable light were the Jews!"[27]

Sayers herself had many Jewish friends, including her publisher, and guests at her salons included from time to time the Chief Rabbi.

Personal life

In London in the 1920s, she entered into an unhappy affair with Russian emigre Imagist poet John Cournos who moved in literary circles with Ezra Pound and his contemporaries. Her affront at his subsequent marriage to a fellow crime writer—after claiming to disdain both monogamy and detective fiction—has been documented in her collected letters,[28] an experience fictionalized a decade later in her novel Strong Poison[29] and in Cournos' The Devil is an English Gentleman, published in 1932.

On 3 January 1924, at the age of 30, Sayers secretly gave birth to an illegitimate son, John Anthony (later surnamed Fleming,[30] though his father was Bill White),[31] who was cared for as a child by her aunt and cousin, Amy and Ivy Amy Shrimpton, and passed off as her nephew to friends.[32][33][34] Two years later, after publishing her first two detective novels, Sayers married Captain Oswald Atherton "Mac" Fleming, a Scottish journalist whose professional name was "Atherton Fleming."[35] The wedding took place on 8 April 1926 at Holborn Register Office, London. Fleming was divorced with two children.

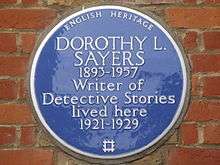

Sayers and Fleming lived in the flat at 24 Great James Street in Bloomsbury[36] that Sayers maintained for the rest of her life. Both worked, Fleming as an author and journalist and Sayers as an advertising copywriter and author. Over time, Fleming's health worsened, largely due to his First World War service, and as a result he became unable to work.

Sayers was a good friend of C. S. Lewis and several of the other Inklings. On some occasions, Sayers joined Lewis at meetings of the Socratic Club. Lewis said he read The Man Born to be King every Easter, but he claimed to be unable to appreciate detective stories. J. R. R. Tolkien read some of the Wimsey novels but scorned the later ones, such as Gaudy Night.[37]

Fleming died on 9 June 1950, at Sunnyside Cottage (now 24 Newland Street), Witham, Essex. Sayers died suddenly of a coronary thrombosis[38] on 17 December 1957 at the same place, aged 64. Fleming was buried in Ipswich, while Sayers's remains were cremated and her ashes buried beneath the tower of St Anne's Church, Soho, London, where she had been a churchwarden for many years. Upon her death it was revealed that her nephew, John Anthony, was her son; he was the sole beneficiary under his mother's will. He died on 26 November 1984 at age 60, in St. Francis's Hospital, Miami Beach, Florida.

Legacy

Some of the dialogue spoken by character Harriet Vane reveals Sayers poking fun at the mystery genre, even while adhering to various conventions.

Sayers' work was frequently parodied by her contemporaries. E. C. Bentley, the author of the early modern detective novel Trent's Last Case, wrote a parody entitled "Greedy Night" (1938).

Sayers was a founder and early president of the Detection Club, an eclectic group of practitioners of the art of the detective novel in the so-called golden age, for whom she constructed an idiosyncratic induction ritual. The Club still exists, and, according to the late P.D. James who was a long-standing member, still uses the ritual. In Sayers' day it was the custom of the members to publish collaborative detective novels, usually writing one chapter each without prior consultation. These works have not held the market, and have only rarely been in print since their first publication.

Her characters, and Sayers herself, have been placed in some other works, including:

- Jill Paton Walsh has published four novels about Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane: Thrones, Dominations (1998), a completion of Sayers' manuscript left unfinished at her death; A Presumption of Death (2002), based on the "Wimsey Papers", letters ostensibly written by various Wimseys and published in The Spectator during the Second World War; The Attenbury Emeralds (2010), based on Lord Peter's "first case", briefly referred to in a number of Sayers' novels; and a sequel The Late Scholar (2013) in which Peter and Harriet have finally become the Duke and Duchess of Denver.

- Wimsey appears (together with Hercule Poirot and Father Brown) in C. Northcote Parkinson's comic novel Jeeves (after Jeeves, the gentleman's gentleman of the P.G. Wodehouse canon).

- Wimsey makes a cameo appearance in Laurie R. King's A Letter of Mary, one of a series of books relating the further adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

- Sayers appears with Agatha Christie as a title character in Dorothy and Agatha [ISBN 0-451-40314-2], a murder mystery by Gaylord Larsen, in which a man is murdered in Sayers' dining room and she has to solve the crime.

- Wimsey is mentioned by Walter Pidgeon's character in the 1945 film Week-End at the Waldorf as one of three possible detectives waiting for him in the hall, outside the apartment of the character played by Ginger Rogers.

- Edward "Rubber Ed" French, the guidance counsellor of Todd Bowden in Stephen King's novella Apt Pupil thinks that Kurt Dussander (alias "Arthur Denker"), who pretends to be Todd's grandfather Victor Bowden, looks like Lord Peter Wimsey.

In Tom Stoppard's play The Real Inspector Hound, one of the critics (Moon) identifies Sayers as a notable literary figure, alongside Kafka, Sartre, Shakespeare, St. Paul, Beckett, Birkett, Pinero, Pirandello, and Dante.[39]

Sayers Classical Academy in Louisville, Kentucky is named after her.

Bibliography

Notes

- ↑ Often pronounced /ˈseɪ.ərz/, but Sayers herself preferred /ˈsɛərz/ and encouraged the use of her middle initial to facilitate this pronunciation. Barbara Reynolds (1993). Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 361. ISBN 0-312-09787-5.

- ↑ Reynolds (1993), pp. 1–14

- ↑ Alzina Stone Dale (2003). Master and CraftsmanThe Story of Dorothy L. Sayers. iUniverse. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-595-26603-6.

- ↑ "Dorothy L. Sayers". Inklings. Taylor University. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Reynolds (1993), p. 43

- ↑ "Biography of DLS". The Dorothy L Sayers Society home pages. The Dorothy L Sayers Society. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ "Op. 1, by Dorothy Sayers". UPenn Digital Libraries: a Celebration of Women Writers. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- 1 2 Murder Must Advertise, chapter 5

- ↑ Mitzi Brunsdale (1990). Dorothy L. Sayers. New York: Berg, p. 94.

- ↑ Randi Sørsdal (2006). From Mystery to Manners: A Study of Five Detective Novels by Dorothy L. Sayers (Masters thesis). University of Bergen. p. 45., bora.uib.no

- ↑ Umberto Eco (2003). Mouse or Rat? Translation as Negotiation. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 141. ISBN 0-297-83001-5.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers (1949). The Divine Comedy 1: Hell (introduction). London: Pengun Books. p. 11.

- ↑ Penguin UK web site (accessed 26 August 2009)

- ↑ Examples, some hilarious, given in Chapter 10 of The Mind of the Maker, include a poet whose solemn ode to the Ark of the Covenant crossing Jordan contains the immortal couplet: "The [something] torrent, leaping in the air / Left the astounded river's bottom bare"

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, The Mind of the Maker, p. 105

- ↑ Sayers, GBT, ISBN 978-1-60051-025-0.

- ↑ Adam Schwartz (2000). "The Mind of a Maker: An Introduction to the Thought of Dorothy L. Sayers Through Her Letters". Touchstone Magazine, Volume 13, Issue 4 (May 2000), pp. 28–38.

- 1 2 3 Sean Latham (2003). Am I A Snob? Modernism and the Novel. Cornell University Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-8014-4022-X.

- ↑ from a letter to his former pupil Norman Malcolm, reproduced on page 109 of Malcolm's Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir, O.U.P., 2001, ISBN 0-19-924759-5

- 1 2 Wilson, Edmund. "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?" Originally published in The New Yorker, 20 January 1945.

- ↑ Leavis 1968, p. 143

- ↑ Leavis 1968, pp. 143–144

- 1 2 Leavis 1968, p. 144

- ↑ Reynolds (1993)

- ↑ James Brabazon, Sayers: A Biography, pp. 216–219

- ↑ Carolyn G. Heilbrun in 'Dorothy L. Sayers: Biography Between the Lines' in Sayers Centenary.

- ↑ From a letter Sayers wrote to David Highan, 27 November 1936, published in Sayers's Letters.

- ↑ An Introduction to the Thought of Dorothy L. Sayers Through Her Letters by Adam Schwartz, Touchstone Magazine

- ↑ SAYERS’ LIFE BETWEEN WORLD WARS I AND II DOROTHY L. SAYERS: HER LIFE AND WORK By Nancy G. West

- ↑ Reynolds (1993), pp. 346

- ↑ Reynolds (1993), pp. 118–122

- ↑ Reynolds (1993), p. 126

- ↑ "gadetection / Sayers, Dorothy L".

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Dorothy L. Sayers". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- ↑ '"Autumn in Galloway"' (1931)' Pastel landscape by Oswald Atherton (Mac) Fleming with photograph of artist

- ↑ Lived in London English Heritage/Yale University Press (2009)

- ↑ The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien p. 95.

- ↑ "Dorothy Sayers, Author, Dies at 64". The New York Times. 19 December 1957. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ Stoppard, Tom (1988). The Real Inspector Hound and Other Plays. Grove Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-8021-3561-7.

References

- Op. I by Dorothy Sayers (poetry): digital.library.upenn.edu

- The Lost Tools of Learning by Dorothy L. Sayers: Audio of this Essay ISBN 978-1-60051-025-0

- Brabazon, James, Dorothy L. Sayers: a Biography (1980; New York: Avon, 1982) ISBN 978-0-380-58990-6

- Dale, Alzine Stone, Maker and Craftsman: The Story of Dorothy L. Sayers (1993; backinprint.com, 2003) ISBN 978-0-595-26603-6

- Leavis, Q.D. (1937). "The Case of Miss Dorothy Sayers". Scrutiny. VI.

- McGregor, Robert Kuhn & Lewis, Ethan Conundrums for the Long Week-End : England, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Lord Peter Wimsey (Kent, OH, & London: Kent State University Press, 2000) ISBN 0-87338-665-5

- Reynolds, Barbara, Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993; rev. eds 1998, 2002) ISBN 0-340-72845-0

- Sørsdal, Randi, From Mystery to Manners: A Study of Five Detective Novels by Dorothy L. Sayers, Masters thesis, University of Bergen, bora.uib.no

- Prescott, Barbara, "Lyric Muse: The Oxford Poetry of Dorothy L. Sayers" (Glen Ellyn: August Press, Inc., 2016)

Further reading and scholarship

- Brown, Janice, The Seven Deadly Sins in the Work of Dorothy L. Sayers (Kent, OH, & London: Kent State University Press, 1998) ISBN 0-87338-605-1

- Connelly, Kelly C. "From Detective Fiction to Detective Literature: Psychology in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers and Margaret Millar." CLUES: A Journal of Detection 25.3 (Spring 2007): 35–47

- Coomes, David, Dorothy L. Sayers: A Careless Rage for Life (1992; London: Chariot Victor Publishing, 1997) ISBN 978-0-7459-2241-6

- Dean, Christopher, ed., Encounters with Lord Peter (Hurstpierpoint: Dorothy L. Sayers Society, 1991) ISBN 0-9518000-0-0

- —, Studies in Sayers: Essays presented to Dr Barbara Reynolds on her 80th Birthday (Hurstpierpoint: Dorothy L. Sayers Society, 1991) ISBN 0-9518000-1-9

- Downing, Crystal, Writing Performances: The Stages of Dorothy Sayers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) ISBN 1-4039-6452-1

- Gorman, Anita G., and Leslie R. Mateer. "The Medium Is the Message: Busman's Honeymoon as Play, Novel, and Film." CLUES: A Journal of Detection 23.4 (Summer 2005): 54–62

- Kenney, Catherine, The Remarkable Case of Dorothy L. Sayers (1990; Kent, OH, & London: Kent State University Press, 1992) ISBN 0-87338-458-X

- Lennard, John, 'Of Purgatory and Yorkshire: Dorothy L. Sayers and Reginald Hill's Divine Comedy', in Of Modern Dragons and other essays on Genre Fiction (Tirril: Humanities-Ebooks, 2007), pp. 33–55. ISBN 978-1-84760-038-7

- Loades, Ann. "Dorothy L. Sayers: War and Redemption." In Hein, David, and Edward Henderson, eds. C. S. Lewis and Friends: Faith and the Power of Imagination, pp. 53–70. London: SPCK, 2011.

- Nelson, Victoria, L. is for Sayers: A Play in Five Acts (Dreaming Spires Publications, 2012) ISBN 0-615-53872-X

- Webster, Peter, 'Archbishop Temple's offer of a Lambeth degree to Dorothy L. Sayers'. In: From the Reformation to the Permissive Society. Church of England Record Society (18). Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge, 2010, pp. 565–582. ISBN 978-1-84383-558-5. Full text in SAS-Space

- Young, Laurel. "Dorothy L. Sayers and the New Woman Detective Novel."CLUES: A Journal of Detection 23.4 (Summer 2005): 39–53

External links

| Library resources about Dorothy L. Sayers |

| By Dorothy L. Sayers |

|---|

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dorothy L. Sayers |

- General

- Archives

- Dorothy Sayers archives at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College

- "Archival material relating to Dorothy L. Sayers". UK National Archives.

- Works by or about Dorothy L. Sayers at Internet Archive

- Works by Dorothy L. Sayers at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Dorothy L. Sayers at Open Library

- Articles

- Dorothy L Sayers in Galloway—the scene of her novel Five Red Herrings (1931)

- "Dorothy L. Sayers: A Christian Humanist for Today" by Mary Brian Durkin

- "Second Glance: Dorothy Sayers and the Last Golden Age" by Joanna Scutts