Dymaxion map

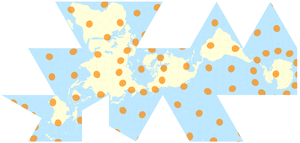

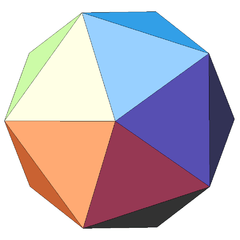

The Dymaxion map or Fuller map is a projection of a world map onto the surface of an icosahedron, which can be unfolded and flattened to two dimensions. The flat map is heavily interrupted in order to preserve shapes and sizes.

The projection was invented by Buckminster Fuller. The March 1, 1943 edition of Life magazine included a photographic essay titled "Life Presents R. Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion World". The article included several examples of its use together with a pull-out section that could be assembled as a "three-dimensional approximation of a globe or laid out as a flat map, with which the world may be fitted together and rearranged to illuminate special aspects of its geography."[1] Fuller applied for a patent in the United States in February 1944, the patent application showing a projection onto a cuboctahedron. The patent was issued in January 1946.[2]

The 1954 version published by Fuller, made with co-cartographer Shoji Sadao, the Airocean World Map, used a modified but mostly regular icosahedron as the base for the projection, which is the version most commonly referred to today. This version depicts the Earth's continents as "one island", or nearly contiguous land masses.

The Dymaxion projection is intended only for representations of the entire globe. It is not a gnomonic projection, whereby global data expands from the center point of a tangent facet outward to the edges. Instead, each triangle edge of the Dymaxion map matches the scale of a partial great circle on a corresponding globe, and other points within each facet shrink toward its middle, rather than enlarging to the peripheries.[3]

The name Dymaxion was applied by Fuller to several of his inventions.

Properties

Fuller claimed that his map had several advantages over other projections for world maps.

It has less distortion of relative size of areas, most notably when compared to the Mercator projection; and less distortion of shapes of areas, notably when compared to the Gall–Peters projection. Other compromise projections attempt a similar trade-off.

More unusually, the Dymaxion map does not have any "right way up". Fuller argued that in the universe there is no "up" and "down", or "north" and "south": only "in" and "out".[4] Gravitational forces of the stars and planets created "in", meaning "towards the gravitational center", and "out", meaning "away from the gravitational center". He attributed the north-up-superior/south-down-inferior presentation of most other world maps to cultural bias.

Fuller intended the map to be unfolded in different ways to emphasize different aspects of the world.[5] Peeling the triangular faces of the icosahedron apart in one way results in an icosahedral net that shows an almost contiguous land mass comprising all of Earth's continents – not groups of continents divided by oceans. Peeling the solid apart in a different way presents a view of the world dominated by connected oceans surrounded by land.

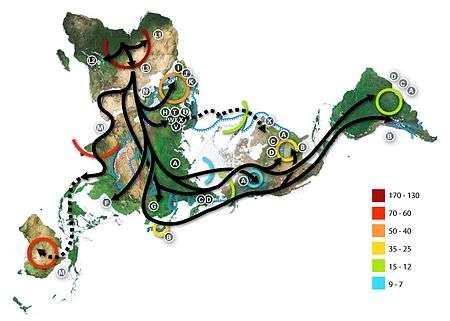

Showing the continents as "one island earth" also helped Fuller explain, in his book Critical Path, the journeys of early seafaring people, who were in effect using prevailing winds to circumnavigate this world island.

Impact

A 1967 Jasper Johns painting, Map (Based on Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion Airocean World), depicting a Dymaxion map, hangs in the permanent collection of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

The World Game, a collaborative simulation game in which players attempt to solve world problems,[6][7] is played on a 70-by-35-foot Dymaxion map.[8]

In 2013, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the publication of the Dymaxion map in Life magazine, the Buckminster Fuller Institute announced the "Dymax Redux", a competition for graphic designers and visual artists to re-imagine the Dymaxion map.[9][10] The competition received over 300 entries from 42 countries.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Life Presents R. Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion World". LIFE: 41–55. 1 March 1943.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 2,393,676

- ↑ Fuller, Ideas and Integrities (1969 ed., p. 139).

- ↑ Fuller, Intuition (1972).

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About The Fuller Projection", Buckminster Fuller Institute, 1992, accessed 2010-07-28

- ↑ Richards, Allen (May–June 1971). "R. Buckminster Fuller: Designer of the Geodesic Dome and the World Game". Mother Earth News. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ Aigner, Hal (November–December 1970). "Sustaining Planet Earth: Researching World Resources". Mother Earth News. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ Perry, Tony (October 2, 1995). "This Game Anything but Child's Play : Buckminster Fuller's creation aims to fight the real enemies of mankind: starvation, disease and illiteracy". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- 1 2 "DYMAX REDUX Winner". The Buckminster Fuller Institute. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey (July 22, 2013). "7 Brilliant Reinventions of Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion Map". Gizmodo. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fuller projection. |

- DYMAX REDUX, a design competition for a fresh take on the dymaxion projection by the Buckminster Fuller Institute

- Fuller Map homepage

- Dymaxion Project Animation

- Icosahedron and Fuller maps

- Dynamically generated maps based on the Dymaxion projection