Edward S. Curtis

| Edward S. Curtis | |

|---|---|

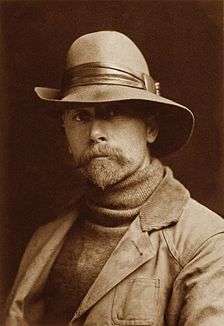

Self-portrait circa 1889 | |

| Born |

Edward Sheriff Curtis February 16, 1868 Whitewater, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died |

October 19, 1952 (aged 84) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Photographer, ethnologist |

| Spouse(s) | Clara J. Phillips (1874–1932) |

| Children |

Harold Curtis (1893–1988) Elizabeth M. Curtis (1896–1973) Florence Curtis Graybill (1899–1987) Katherine Curtis (1909–unknown) |

| Parent(s) |

Ellen Sheriff (1844–1912) Johnson Asahel Curtis (1840–87) |

Edward Sheriff Curtis (February 16, 1868 – October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American peoples.[1][2]

Early life

Curtis was born on February 16, 1868, on a farm near Whitewater, Wisconsin.[3][4] His father, the Reverend Asahel "Johnson" Curtis (1840–1887), was a minister, farmer, and American Civil War veteran[5] born in Ohio. His mother, Ellen Sheriff (1844–1912), was born in Pennsylvania. Curtis's siblings were Raphael (1862–c.1885), also called Ray; Edward, called Eddy; Eva (1870–?); and Asahel Curtis (1874–1941).[3] Weakened by his experiences in the Civil War, Johnson Curtis had difficulty in managing his farm, resulting in hardship and poverty for his family.[3]

Around 1874, the family moved from Wisconsin to Minnesota to join Johnson Curtis's father, Asahel Curtis, who ran a grocery store and was a postmaster in Le Sueur County.[3][5] Curtis left school in the sixth grade and soon built his own camera.

Career

Early career

_of_the_Duwamish%2C_1896.jpg)

In 1885, at the age of 17, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1887 the family moved to Seattle, Washington, where he purchased a new camera and became a partner with Rasmus Rothi in an existing photographic studio. Curtis paid $150 for his 50% share in the studio. After about six months, he left Rothi and formed a new partnership with Thomas Guptill. They established a new studio, Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers.[2][4]

In 1895, Curtis met and photographed Princess Angeline (c. 1820–1896), also known as Kickisomlo, the daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. This was his first portrait of a Native American. In 1898, three of Curtis's images were chosen for an exhibition sponsored by the National Photographic Society. Two were images of Princess Angeline, "The Mussel Gatherer" and "The Clam Digger". The other was of Puget Sound, entitled "Homeward", which was awarded the exhibition's grand prize and a gold medal.[6] In that same year, while photographing Mt. Rainier, Curtis came upon a small group of scientists. One of them was George Bird Grinnell, considered an "expert" on Native Americans by his peers. Curtis was appointed the official photographer of the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899, probably as a result of his friendship with Grinnell. Having very little formal education Curtis learned much during the lectures that were given aboard the ship each evening of the voyage.[7] Grinnell became interested in Curtis's photography and invited him to join an expedition to photograph people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Montana in 1900.[2]

The North American Indian

In 1906, J. P. Morgan provided Curtis with $75,000 to produce a series on Native Americans.[8] This work was to be in 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs. Morgan's funds were to be disbursed over five years and were earmarked to support only fieldwork for the books, not for writing, editing, or production of the volumes. Curtis received no salary for the project,[9] which was to last more than 20 years. Under the terms of the arrangement, Morgan was to receive 25 sets and 500 original prints as repayment.

Once Curtis had secured funding for the project, he was able to hire several employees to help him. For writing and for recording Native American languages, he hired a former journalist, William E. Myers.[9] For general assistance with logistics and fieldwork, he hired Bill Phillips, a graduate of the University of Washington. Perhaps the most important hire for the success of the project was Frederick Webb Hodge, an anthropologist employed by the Smithsonian Institution, who had researched Native American peoples of the southwestern United States.[9] Hodge was hired to edit the entire series.

Eventually 222 complete sets were published. Curtis's goal was not just to photograph but also to document as much of Native American traditional life as possible before that way of life disappeared. He wrote in the introduction to his first volume in 1907, "The information that is to be gathered ... respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost." Curtis made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Native American language and music. He took over 40,000 photographic images of members of over 80 tribes. He recorded tribal lore and history, and he described traditional foods, housing, garments, recreation, ceremonies, and funeral customs. He wrote biographical sketches of tribal leaders. His material, in most cases, is the only written recorded history, although there is still a rich oral tradition that preserves history.[2][10] His work was exhibited at the Rencontres d'Arles festival in France in 1973.

In the Land of the Head Hunters

Curtis had been using motion picture cameras in fieldwork for The North American Indian since 1906.[9] He worked extensively with the ethnographer and British Columbia native George Hunt in 1910, which inspired his work with the Kwakiutl, but much of their collaboration remains unpublished.[11] At the end of 1912, Curtis decided to create a feature film depicting Native American life, partly as a way of improving his financial situation and partly because film technology had improved to the point where it was conceivable to create and screen films more than a few minutes long. Curtis chose the Kwakiutl tribe, of the Queen Charlotte Strait region of the Central Coast of British Columbia, Canada, for his subject. His film, In the Land of the Head Hunters, was the first feature-length film whose cast was composed entirely of Native North Americans.[12]

In the Land of the Head-Hunters premiered simultaneously at the Casino Theatre in New York and the Moore Theatre in Seattle on December 7, 1914.[12] The silent film was accompanied by a score composed by John J. Braham, a musical theater composer who had also worked with Gilbert and Sullivan. The film was praised by critics but made only $3,269.18 in its initial run.[13]

Later years

The photographer Ella E. McBride assisted Curtis in his studio beginning in 1907 and became a friend of the family. She made an unsuccessful attempt to purchase the studio with Curtis's daughter Beth in 1916, the year of Curtis's divorce, and left to open her own studio.[14]

Around 1922, Curtis moved to Los Angeles with Beth and opened a new photo studio. To earn money he worked as an assistant cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille and was an uncredited assistant cameraman in the 1923 filming of The Ten Commandments. On October 16, 1924, Curtis sold the rights to his ethnographic motion picture In the Land of the Head-Hunters to the American Museum of Natural History. He was paid $1,500 for the master print and the original camera negative. It had cost him over $20,000 to create the film.[2]

In 1927, after returning from Alaska to Seattle with Beth, Curtis was arrested for failure to pay alimony over the preceding seven years. The total owed was $4,500, but the charges were dropped. For Christmas of 1927, the family was reunited at the home of his daughter Florence in Medford, Oregon. This was the first time since the divorce that Curtis was with all of his children at the same time, and it had been 13 years since he had seen Katherine.

In 1928, desperate for cash, Curtis sold the rights to his project to J. P. Morgan, Jr. The concluding volume of The North American Indian was published in 1930. In total, about 280 sets were sold of his now completed magnum opus.

In 1930, his ex-wife, Clara, was still living in Seattle operating the photo studio with their daughter Katherine. His other daughter, Florence Curtis, was still living in Medford, Oregon, with her husband, Henry Graybill. After Clara died of heart failure in 1932,[15] his daughter Katherine moved to California to be closer to her father and Beth.[2]

Loss of rights to The North American Indian

In 1935, the Morgan estate sold the rights to The North American Indian and remaining unpublished material to the Charles E. Lauriat Company in Boston for $1,000 plus a percentage of any future royalties. This included 19 complete bound sets of The North American Indian, thousands of individual paper prints, the copper printing plates, the unbound printed pages, and the original glass-plate negatives. Lauriat bound the remaining loose printed pages and sold them with the completed sets. The remaining material remained untouched in the Lauriat basement in Boston until they were rediscovered in 1972.[2]

Personal life

Marriage and divorce

In 1892, Curtis married Clara J. Phillips (1874–1932), who was born in Pennsylvania. Her parents were from Canada. Together they had four children: Harold (1893–1988); Elizabeth M. (Beth) (1896–1973), who married Manford E. Magnuson (1895–1993); Florence (1899–1987), who married Henry Graybill (1893–?); and Katherine (Billy) (1909–?).

In 1896, the entire family moved to a new house in Seattle. The household then included Curtis's mother, Ellen Sheriff; his sister, Eva Curtis; his brother, Asahel Curtis; Clara's sisters, Susie and Nellie Phillips; and their cousin, William.

During the years of work on The North American Indian, Curtis was often absent from home for most of the year, leaving Clara to manage the children and the studio by herself. After several years of estrangement, Clara filed for divorce on October 16, 1916. In 1919 she was granted the divorce and received Curtis's photographic studio and all of his original camera negatives as her part of the settlement. Curtis and his daughter Beth went to the studio and destroyed all of his original glass negatives, rather than have them become the property of his ex-wife. Clara went on to manage the Curtis studio with her sister Nellie (1880–?), who was married to Martin Lucus (1880–?). Following the divorce, the two oldest daughters, Beth and Florence, remained in Seattle, living in a boarding house separate from their mother. The youngest daughter, Katherine, lived with Clara in Charleston, Kitsap County, Washington.[2]

Death

On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a heart attack in Los Angeles, California, in the home of his daughter Beth. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. A brief obituary appeared in The New York Times on October 20, 1952:

Edward S. Curtis, internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Beth Magnuson. His age was 84. Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, J. Pierpont Morgan. The foreward [sic] for the monumental set of Curtis books was written by President Theodore Roosevelt. Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.[1]

Collections of Curtis materials

Northwestern University

The entire 20 volumes of narrative text and photogravure images for each volume are online.[16] Each volume is accompanied by a portfolio of large photogravure plates. The online publishing was supported largely by funds from the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

Library of Congress

The Prints and Photographs Division Curtis collection consists of more than 2,400 silver-gelatin, first-generation photographic prints – some of which are sepia-toned – made from Curtis's original glass negatives. Most are 5 by 7 inches (13 cm × 18 cm) although nearly 100 are 11 by 14 inches (28 cm × 36 cm) and larger; many include the Curtis file or negative number in the lower left-hand corner of the image.

The Library of Congress acquired these images as copyright deposits from about 1900 through 1930. The dates on them are dates of registration, not the dates when the photographs were taken. About two-thirds (1,608) of these images were not published in The North American Indian and therefore offer a different glimpse into Curtis's work with indigenous cultures. The original glass plate negatives, which had been stored and nearly forgotten in the basement of the Morgan Library, in New York, were dispersed during World War II. Many others were destroyed and some were sold as junk.[4]

Charles Lauriat archive

Around 1970, Karl Kernberger, of Santa Fe, New Mexico, went to Boston to search for Curtis's original copper plates and photogravures at the Charles E. Lauriat rare bookstore. He discovered almost 285,000 original photogravures as well as all the copper plates. With Jack Loeffler and David Padwa, they jointly purchased all of the surviving Curtis material that was owned by Charles Emelius Lauriat (1874–1937). The collection was later purchased by another group of investors led by Mark Zaplin, of Santa Fe. The Zaplin Group owned the plates until 1982, when they sold them to a California group led by Kenneth Zerbe, the owner of the plates as of 2005.

Peabody Essex Museum

Charles Goddard Weld purchased 110 prints that Curtis had made for his 1905–06 exhibit and donated them to the Peabody Essex Museum, where they remain. The 14" by 17" prints are each unique and remain in pristine condition. Clark Worswick, curator of photography for the museum, describes them as:

...Curtis' most carefully selected prints of what was then his life’s work...certainly these are some of the most glorious prints ever made in the history of the photographic medium. The fact that we have this man’s entire show of 1906 is one of the minor miracles of photography and museology.[17]

Indiana University

Two hundred seventy-six of the wax cylinders made by Curtis between 1907 and 1913 are held by the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University.[18] These include recordings of music of the following Native American groups: Clayoquot, Cowichan, Haida, Hesquiat, and Kwakiutl, in British Columbia; and Arapaho, Cheyenne, Cochiti, Crow, Klikitat, Kutenai, Nez Percé, Salish, Shoshoni, Snohomish, Wishram, Yakima, Acoma, Arikara, Hidatsa, Makah, Mandan, Paloos, Piegan, Tewa (San Ildefonso, San Juan, Tesuque, Nambé), and possibly Dakota, Clallam, Twana, Colville and Nespelim in the western United States.

University of Wyoming

Toppan Rare Books Library at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming, holds the entire 20 volumes of narrative text and photogravure images. Each volume is accompanied by a portfolio of large photogravure plates.

Legacy

Revival of interest

Though Curtis was largely forgotten at the time of his death, interest in his work revived in the 1970s. Major exhibitions of his photographs were presented at the Morgan Library & Museum (1971),[19] the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1972),[20] and the University of California, Irvine (1976).[21] His work was also featured in several anthologies on Native American photography published in the early 1970s.[22] Original printings of The North American Indian began to fetch high prices at auction. In 1972, a complete set sold for $20,000. Five years later, another set was auctioned for $60,500.[23] The revival of interest in Curtis's work can be seen as part of the increased attention to Native American issues during this period.

Critical reception

A representative evaluation of The North American Indian is that of Mick Gidley, Emeritus Professor of American Literature, at Leeds University, in England, who has written a number of works related to the life of Curtis: "The North American Indian—extensively produced and issued in a severely limited edition—could not prove popular. But in recent years anthropologists and others, even when they have censured what they have assumed were Curtis' methodological assumptions or quarrelled with the text's conclusions, have begun to appreciate the value of the project's achievement: exhibitions have been mounted, anthologies of pictures have been published, and The North American Indian has increasingly been cited in the researches of others... The North American Indian is not monolithic or merely a monument. It is alive, it speaks, if with several voices, and among those perhaps mingled voices are those of otherwise silent or muted Indian individuals.”[24]

Of the full Curtis opus N. Scott Momaday wrote, "Taken as a whole, the work of Edward S. Curtis is a singular achievement. Never before have we seen the Indians of North America so close to the origins of their humanity...Curtis' photographs comprehend indispensable images of every human being at every time in every place"[25]

Don Gulbrandsen, the author of Edward Sheriff Curtis: Visions of the First Americans, put it this way in his introductory essay on Curtis’s life: “The faces stare out at you, images seemingly from an ancient time and from a place far, far away…Yet as you gaze at the faces the humanity becomes apparent, lives filled with dignity but also sadness and loss, representatives of a world that has all but disappeared from our planet.”

In Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, Laurie Lawlor revealed that “many Native Americans Curtis photographed called him Shadow Catcher. But the images he captured were far more powerful than mere shadows. The men, women, and children in The North American Indian seem as alive to us today as they did when Curtis took their pictures in the early part of the twentieth century. Curtis respected the Native Americans he encountered and was willing to learn about their culture, religion and way of life. In return the Native Americans respected and trusted him. When judged by the standards of his time, Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance, and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking.”[26]

Theodore Roosevelt, a contemporary of Curtis's and one of his most fervent supporters, wrote the following comments in the foreword to Volume 1 of The North American Indian:

In Mr. Curtis we have both an artist and a trained observer, whose work has far more than mere accuracy, because it is truthful. …because of his extraordinary success in making and using his opportunities, has been able to do what no other man ever has done; what, as far as we can see, no other man could do. Mr. Curtis in publishing this book is rendering a real and great service; a service not only to our own people, but to the world of scholarship everywhere.

Curtis has been praised as a gifted photographer but also criticized by some contemporary ethnologists for manipulating his images. Although the early twentieth century was a difficult time for most Native communities in America, not all natives were doomed to becoming a "vanishing race."[27] At a time when natives' rights were being denied and their treaties were unrecognized by the federal government, many natives were successfully adapting to Western society. Some believe that by reinforcing the native identity as the noble savage and a tragic vanishing race, some believe Curtis deflected attention from the true plight of American natives at the time when he was witnessing their squalid conditions on reservations first-hand and their attempt to find their place in Western culture and adapt to their changing world.[27]

Curtis removed parasols, suspenders, wagons, and other traces of Western material culture from many of his images. In his photogravure In a Piegan Lodge, published in The North American Indian, Curtis retouched the image to remove a clock between the two men seated on the ground.[28]

He also is known to have paid natives to pose in staged scenes, wear historically inaccurate dress and costumes, dance and partake in simulated ceremonies.[29] In Curtis's picture Oglala War-Party, the image shows 10 Oglala men wearing feather headdresses, on horseback riding down hill. The photo caption reads, "a group of Sioux warriors as they appeared in the days of inter tribal warfare, carefully making their way down a hillside in the vicinity of the enemy's camp". In truth, headdresses would have been worn only for special occasions and, in some tribes, only by the chief of the tribe. The photograph was taken in 1907, when natives had been relegated to reservations and warring between tribes had ended. Curtis paid natives to pose as warriors at a time when they lived with little dignity and few rights and freedoms. It has been suggested that he altered and manipulated his pictures to create an ethnographic simulation of native tribes untouched by Western society.

Image gallery

A smoky day at the Sugar Bowl—Hupa, c. 1923. Hupa man with spear, standing on rock midstream, in background, fog partially obscures trees on mountainsides.

A smoky day at the Sugar Bowl—Hupa, c. 1923. Hupa man with spear, standing on rock midstream, in background, fog partially obscures trees on mountainsides.

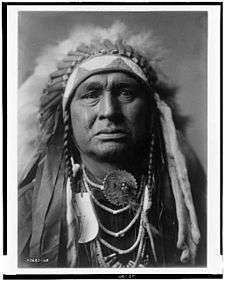

White Man Runs Him, c. 1908. Crow scout serving with George Armstrong Custer’s 1876 expeditions against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

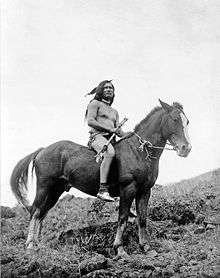

White Man Runs Him, c. 1908. Crow scout serving with George Armstrong Custer’s 1876 expeditions against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The old-time warrior: Nez Percé, c. 1910. Nez Percé man, wearing loin cloth and moccasins, on horseback.

The old-time warrior: Nez Percé, c. 1910. Nez Percé man, wearing loin cloth and moccasins, on horseback.- Crow's Heart, Mandan, c. 1908

Mandan man overlooking the Missouri River, c. 1908

Mandan man overlooking the Missouri River, c. 1908

- Mandan girls gathering berries, c. 1908

Mandan hunter with buffalo skull, c. 1909

Mandan hunter with buffalo skull, c. 1909 Zuni Girl with Jar, c. 1903. Head-and-shoulders portrait of a Zuni girl with a pottery jar on her head.

Zuni Girl with Jar, c. 1903. Head-and-shoulders portrait of a Zuni girl with a pottery jar on her head.

Navaho medicine-man, c. 1904 (with 1913 signature)

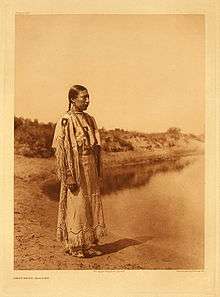

Navaho medicine-man, c. 1904 (with 1913 signature) Cheyenne maiden, 1930

Cheyenne maiden, 1930 Hopi mother, 1922

Hopi mother, 1922 Hopi girl, 1922

Hopi girl, 1922

Canyon de Chelly – Navajo. Seven riders on horseback and dog trek against background of canyon cliffs, 1904

Canyon de Chelly – Navajo. Seven riders on horseback and dog trek against background of canyon cliffs, 1904 Apache Scout, c. 1900s

Apache Scout, c. 1900s Apache, Morning bath, c. 1907

Apache, Morning bath, c. 1907 Mandan lodge, North Dakota, c. 1908

Mandan lodge, North Dakota, c. 1908 Food caches, Hooper Bay, Alaska, c. 1929

Food caches, Hooper Bay, Alaska, c. 1929

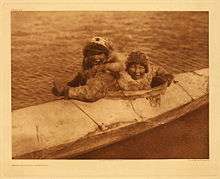

Boys in kayak, Nunivak, 1930

Boys in kayak, Nunivak, 1930

Timeline

- 1868 – Born near Whitewater, Wisconsin; he grows up near Cordova, Minnesota.

- 1887 – Moves to Washington Territory with his father.

- 1891 – Forms a partnership in a photo studio with Rothi in Seattle, Washington; later starts a second studio with Guptill.

- 1895 – Photographs Princess Angeline.

- 1896 – Wins the bronze medal at the National Photographers Convention in Chautauqua, New York. Argus magazine praises his work. Beth, his second child and first daughter, is born. The family moves to a larger house.

- 1898 – Meets George Bird Grinnell and C. Hart Merriam while hiking on Mount Rainier.

- 1899 – Is appointed photographer for the Harriman Alaska Expedition.

- 1900 – Accompanies George Bird Grinnell to the Piegan Blackfeet reservation in Montana to photograph the Sun Dance ceremony.

- 1903 – Photographs Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce people.

- 1903 – Travels to Manhattan, New York City and Washington, District of Columbia, while Adolph Muhr (?–1912) runs the studio.

- 1904 – Theodore Roosevelt invites him to photograph his children after seeing a Curtis photograph published in Ladies' Home Journal.

- 1904 – Louisa Morgan Satterlee, daughter of the financier J. P. Morgan, purchases Curtis photographs at an exhibit in New York City.

- 1906 – Secures funds from J. P. Morgan for the field work to produce a twenty-volume illustrated text on Native Americans, to be completed in five years.[8]

- 1907 – Volume 1 of The North American Indian is published, with a foreword by Theodore Roosevelt.[8]

- 1908 – Volume 2 published.

- 1911 – Launches The Indian Picture Opera, a lecture and slide show, to publicize his work and solicit subscriptions for The North American Indian. Original music was composed by Henry Gilbert, and a 22-piece orchestra accompanied the production. The Indian Picture Opera was performed through the end of 1912.[35][36]

- 1912 – Volume 8 published.

- 1913 – J. P. Morgan dies. His son continues funding The North American Indian until its completion.

- 1913 – Volume 9 published.[37]

- 1914 – Releases In the Land of the Head-Hunters, a motion picture depicting Native Americans of the Northwest Coast.[38]

- 1915 – Volume 10 and volume 11 published.

- 1916 – Clara Curtis files for divorce.

- 1916 – Works on the orotone photographic process.

- 1919 – Divorce granted from Clara Curtis.

- 1920 – Clara living in Charleston, Kitsap County, Washington, with her married sister.

- 1920 – Moves with his daughter Beth from Seattle, Washington, to Los Angeles, California

- 1920 – Sets up a new studio in Hollywood, California, and works as a still photographer and assistant movie camera operator for film studios.

- 1922 – Volume 12 published.

- 1924 – Sells rights to his film to the American Museum of Natural History, in Manhattan.

- 1926 – Volume 16 published.

- 1927 – Alaska trip.

- 1927 – His youngest daughter, Katherine, visits with the family at her sister Florence's home in Medford, Oregon, the first time he had been with all of his children in 13 years.

- 1930 – Volume 20 published. Daughters Clara and Katherine living in Seattle and operating his original studio.

- 1932 – Death of his ex-wife, Clara; his daughter Katherine moves to California.

- 1935 – Copper photogravure plates from The North American Indian sold to the Charles E. Lauriat Company, a rare book dealer in Boston, Massachusetts.

- 1947 – Moves to Whittier, California, into the home of his daughter Beth and her husband Manford Magnuson.

- 1952 – Dies in Los Angeles, California in Beth's home; his obituary appears in the New York Times; he is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, California.[1]

Works

Books

- The North American Indian. 20 volumes (1907–1930)

- Volume 1 (1907): The Apache. The Jicarillas. The Navaho.

- Volume 2 (1908): The Pima. The Papago. The Qahatika. The Mohave. The Yuma. The Maricopa. The Walapai. The Havasupai. The Apache-Mohave, or Yavapai.

- Volume 3 (1908): The Teton Sioux. The Yanktonai. The Assiniboin.

- Volume 4 (1909): The Apsaroke, or Crows. The Hidatsa.

- Volume 5 (1909): The Mandan. The Arikara. The Atsina.

- Volume 6 (1911): The Piegan. The Cheyenne. The Arapaho.

- Volume 7 (1911): The Yakima. The Klickitat. Salishan tribes of the interior. The Kutenai.

- Volume 8 (1911): The Nez Perces. Wallawalla. Umatilla. Cayuse. The Chinookan tribes.

- Volume 9 (1913): The Salishan tribes of the coast. The Chimakum and the Quilliute. The Willapa.

- Volume 10 (1915): The Kwakiutl.

- Volume 11 (1916): The Nootka. The Haida.

- Volume 12 (1922): The Hopi.

- Volume 13 (1924): The Hupa. The Yurok. The Karok. The Wiyot. Tolowa and Tututni. The Shasta. The Achomawi. The Klamath.

- Volume 14 (1924): The Kato. The Wailaki. The Yuki. The Pomo. The Wintun. The Maidu. The Miwok. The Yokuts.

- Volume 15 (1926): Southern California Shoshoneans. The Diegueños. Plateau Shoshoneans. The Washo.

- Volume 16 (1926): The Tiwa. The Keres.

- Volume 17 (1926): The Tewa. The Zuñi.

- Volume 18 (1928): The Chipewyan. The Western Woods Cree. The Sarsi.

- Volume 19 (1930): The Indians of Oklahoma. The Wichita. The Southern Cheyenne. The Oto. The Comanche. The Peyote Cult.

- Volume 20 (1930): The Alaskan Eskimo. The Nunivak. The Eskimo of Hooper Bay. The Eskimo of King Island. The Eskimo of Little Diomede Island. The Eskimo of Cape Prince of Wales. The Kotzebue Eskimo. The Noatak. The Kobuk. The Selawik.

- Indian Days of the Long Ago (1914)

- In the Land of the Head-Hunters (1915)

Articles

- "The Rush to the Klondike Over the Mountain Pass". The Century Magazine, March 1898, pp. 692–697.

- "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Southwest". Scribner's Magazine 39:5 (May 1906): 513–529.

- "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains". Scribner's Magazine 39:6 (June 1906): 657–71.

- "Indians of the Stone Houses". Scribner's Magazine 45:2 (1909): 161–75.

- "Village Tribes of the Desert Land. Scribner's Magazine 45:3 (1909): 274–87.

Brochures

- The North American Indian. (promotional brochure) (1914?)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Edward S. Curtis, internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Bess Magnuson. His age was 84". The New York Times. October 20, 1952.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Makepeace, Anne (2001). Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light. National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-6404-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Laurie Lawlor (1994). Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis. New York: Walker.

- 1 2 3 "Edward S. Curtis Collection". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

Although unknown for many years, Edward S. Curtis is today one of the most well-recognized and celebrated photographers of Native people. Born near White Water,(sic) Wisconsin, on February 16, 1868, he became interested in the emerging art of photography when he was quite young, building his first camera when he was still an adolescent. In Seattle, where his family moved in 1887, he acquired part interest in a portrait photography studio and soon became sole owner of the successful business, renaming it Edward S. Curtis Photographer and Photoengraver.

- 1 2 "Shadow Catcher". American Masters. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Edward S. Curtis and The North American Indian: A Detailed Chronological Biography". Soul Catcher Studio. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ↑ Gidley, Mick. "Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) and The North American Indian". Library of Congress American Memory. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "American Indian in 'Photo History'". The New York Times. June 6, 1908. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Egan, Timothy (2012). Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 370. ISBN 0618969020.

- ↑ Vaughn, Chris (September 21, 2009). "Fort Worth's Amon Carter Museum Acquires a Long-Sought Masterpiece of American Indian Photography". Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ Glass, Aaron (2009). "A Cannibal in the Archive: Performance, Materiality, and (In)Visibility in Unpublished Edward Curtis Photographs of the Kwakwaka'wakw Hamats". Visual Anthropology Review. 25: 128–149. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7458.2009.01038.x.

- 1 2 "Web site for In the Land of the Head Hunters re-release, a joint project of U'mista and Rutgers University". Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ↑ Arnold, William (July 8, 2008). "Edward Curtis' 'Head Hunters' takes another bow with film festival screening". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ↑ Martin, David M. (March 3, 2008). "McBride, Ella E. (1862–1965)". HistoryLink.org – The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Certificate of death for Clara J. Curtis, Center for Health Statistics, Department of Health, State of Washington.

- ↑ http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/

- ↑ "The Master Prints of Edwards S. Curtis: Portraits of Native America". Peabody Essex Museum. Archived from the original on January 28, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

Edward Sheriff Curtis was just thirty-three years old in 1901 when he began his legendary effort to document the life and cultures of the North American Indian through photographs and interviews. By 1930 he had studied more than eighty tribes, taken more than 40,000 photographs, and earned the support of Theodore Roosevelt and J. P. Morgan, among others.

- ↑ Archives of Traditional Music

- ↑ Thornton, Gene (October 17, 1971). "Why Is Curtis Unknown to Photographic History?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Curtis, Edward S. (1972). The North American Indians: A Selection of Photographs. New York: Aperture. ISBN 0912334347.

- ↑ "UC Irvine University Art Galleries". Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ↑ McLuhan, T. C. (1971). Touch the Earth: A Self-Portrait of Indian Existence. New York: Outerbridge & Dienstfrey. ISBN 9780876900383.

- ↑ Solis-Cohen, Lita (February 9, 1979). "Art Thieves Know the Product". Toledo Blade. Toledo, Ohio. p. 15.

- ↑ Gidley, Mick (2001). "Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) and The North American Indian". Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ↑ Momaday, N. Scott; Horse Capture, Joseph D.; Makepeace, Anne (2005). Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian. Burlington: Verve. ISBN 0976912716.

- ↑ Lawlor, Laurie; Curtis, Edward S. (2005). Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis (Reprint ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 6. ISBN 0803280467.

- 1 2 "The Myth of the Vanishing Race". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- ↑ "The Shadow Catcher". Retrieved August 26, 2007.

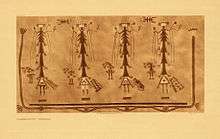

- ↑ Description by Curtis: "A well-known Navaho medicine-man. While in the Cañon de Chelly the writer witnessed a very interesting four days' ceremony given by the Wind Doctor. Nesjaja Hatali was also assistant medicine-man in two nine days' ceremonies studied – one in Cañon del Muerto and the other in this portfolio (No. 39) is reproduced from one made and used by this priest-doctor in the Mountain Chant."

- ↑ Description by Curtis: "This portrait of the historical old Apache was made in March, 1905. According to Geronimo's calculation he was at the time seventy-six years of age, thus making the year of his birth 1829. The picture was taken at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the day before the inauguration of President Roosevelt, Geronimo being one of the warriors who took part in the inaugural parade at Washington."

- ↑ Description by Curtis: "The Navaho might as well be called the 'Keepers of Flocks'. Their sheep are of the greatest importance to their existence, and in the care and management of their flocks they exhibit a thrift not to be found in the average tribe."

- ↑ Description by Curtis: "One of the four elaborate dry-paintings or sand altars employed in the rites of the Mountain Chant, a Navaho medicine ceremony of nine days' duration."

- ↑ Description by Curtis: "The Navaho-land blanket looms are in evidence everywhere. In the winter months they are set up in the hogans, but during the summer they are erected outdoors under an improvised shelter, or, as in this case, beneath a tree. The simplicity of the loom and its product are here clearly shown, pictured in the early morning light under a large cottonwood."

- ↑ "Lives 22 Years with Indians to Get Their Secrets". The New York Times. April 16, 1911. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

With the aid of J. Pierpont Morgan, Edward S. Curtis has finished more than half of his monumental study of the American Indian. He has spent fourteen years among them in this work, and calculates that eight more years will see the completion of it.

- ↑ Charles Rice (October 14, 1911). "Mount Tacoma". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

Many acres of forest land have been denuded in order to furnish the paper on which have been printed the voluminous and sometimes acrimonious discussion as to the meaning of the word 'Tacoma'. Edward S. Curtis, the Indian authority, who has been highly commended by The Times thus disposes of the question in the seventh volume of his great work, The North America Indian.

- ↑ "The American Indian". The New York Times. September 7, 1913. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

The appearance of Volume IX. of "The North American Indian," a field research conducted under the patronage of the late Pierpont Morgan, brings before the public another section of this valuable and comprehensive study of a people who are rapidly disappearing or losing their aboriginal traits, and acquiring the manners and customs of the dominant white race.

- ↑ "Head-Hunters: Mr. Curtis's Account of an Alaskan Tribe". The New York Times. March 28, 1915. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

Edward S. Curtis has for many years been identified with the North American Indian. To them and their customs and languages he has given the study of a lifetime, living as friend and brother with the men of different tribes, permitted to watch them in their everyday life as well as in the exercise of their ceremonials.

Further reading

- Cardozo, Christopher (1993). Native Nations: First Americans as Seen by Edward S. Curtis. Boston: Bullfinch Press.

- Cardozo, Christopher (2004). Edward S. Curtis: The Great Warriors. Boston: Bullfinch Press.

- Cardozo, Christopher (2005). Edward S. Curtis: The Women. Boston: Bullfinch Press.

- Cardozo, Christopher (2015). Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks. New York: DelMonico Books - Prestel.

- Curtis, Edward S (2005). The North American Indian (25th anniversary ed.). Cologne: Taschen.

- Curtis, Edward S.; Cardozo, Christopher (2000). Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Davis, Barbara A (1985). Edward S. Curtis: The Life and Times of a Shadow Catcher. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

- Egan, Timothy (2012). Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-96902-0.

- Gidley, Mick (1998). Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian, Incorporated. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77573-6.

- Gidley, Mick (2003). Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian Project in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Makepeace, Anne (2002). Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.

- Scherer, Joanna Cohan (2008). Edward Sheriff Curtis. London: Phaidon.

- Touchie, Roger D (2010). Edward S. Curtis Above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. Toronto: Heritage House.

- Zamir, Shamoon (2014). The Gift of the Face. Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Sheriff Curtis. |

- "Epic photographic odyssey that documented Native Americans (video)". BBC News Online. November 28, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- Works by Edward S. Curtis at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward S. Curtis at Internet Archive

- "Edward S. Curtis". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- Edward Curtis at the Internet Movie Database

- American Masters: Edward Curtis

- Smithsonian: Edward Curtis

- Library of Congress Print Collection: Edward Curtis

- Library of Congress Exhibit: Edward Curtis

- Northwestern University Library: Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian

- Edward Curtis: Selling the North American Indian Hypertext Critical Biography with images, video, images of books, articles and promotional material from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Indian days of the long ago, by Edward S. Curtis; illustrated with photos. by the author and drawings by F. N. Wilson, 1915, c1914. (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Edward Curtis at Museum Syndicate

- Edward S. Curtis papers at the Getty Research Institute

- Peabody Essex Museum: The Master Prints of Edward S. Curtis exhibition, 2001–2002

- oldpicture.com: Complete Edward Curtis Collection

- Original vintage photos, exhibits, lectures, film screenings, and special events focus on the work of photographer Edward Curtis in Bend, OR Sept. 4 - Oct. 31, 2015

- 1904-1924 'The North American Indian' Edward Sheriff Curtis photographs