Edward Thomas (poet)

| Philip Edward Thomas | |

|---|---|

Thomas in 1905 | |

| Born |

3 March 1878 Lambeth, Surrey, England |

| Died |

9 April 1917 (aged 39) Pas-de-Calais, France |

| Pen name | Edward Thomas, Edward Eastaway |

| Occupation | Journalist, essayist, and poet |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Nature poetry, War poetry |

| Subject | Nature, War |

| Spouse | Helen Berenice Noble/Thomas |

| Children | One son (Merfyn), two daughters (Bronwen and Myfanwy) |

Philip Edward Thomas (3 March 1878 – 9 April 1917) was a British poet, essayist, and novelist. He is commonly considered a war poet, although few of his poems deal directly with his war experiences, and his career in poetry only came after he had already been a successful writer and literary critic. In 1915, he enlisted in the British Army to fight in the First World War and was killed in action during the Battle of Arras in 1917, soon after he arrived in France.

Life and career

Early life

Thomas was born in Lambeth, London. He was educated at Battersea Grammar School, St Paul's School in London and Lincoln College, Oxford. His family were mostly Welsh. In June 1899 he married Helen Berenice Noble (1878–1967),[1] in Fulham, while still an undergraduate, and determined to live his life by the pen. He then worked as a book reviewer, reviewing up to 15 books every week.[2] He was already a seasoned writer by the outbreak of war, having published widely as a literary critic and biographer as well writing on the countryside. He also wrote a novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913), a "book of delightful disorder".[3]

Thomas worked as literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London and became a close friend of Welsh tramp poet W. H. Davies, whose career he almost single-handedly developed.[4]

From 1905, Thomas lived with his wife Helen and their family at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks, Kent. He rented to Davies a tiny cottage nearby, and nurtured his writing as best he could. On one occasion, Thomas even had to arrange for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift wooden leg for Davies.

Even though Thomas thought that poetry was the highest form of literature and regularly reviewed it, he only became a poet himself at the end of 1914[2] when living at Steep, East Hampshire, and initially published his poetry under the name Edward Eastaway. Frost in particular encouraged Thomas (then more famous as a critic) to write poetry, and their friendship was so close that the two planned to reside side by side in the United States.[6]

By August 1914, the village of Dymock in Gloucestershire had become the residence of a number of literary figures, including Lascelles Abercrombie, Wilfrid Gibson and American poet Robert Frost. Edward Thomas was a visitor at this time.[7]

Thomas immortalised the (now-abandoned) railway station at Adlestrop in a poem of that name after his train made a stop at the Cotswolds station on 24 June 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War.[8]

War service

Thomas enlisted in the Artists Rifles in July 1915, despite being a mature married man who could have avoided enlisting. He was unintentionally influenced in this decision by his friend Frost, who had returned to the U.S. but sent Thomas an advance copy of "The Road Not Taken".[9] The poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision, particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together; however, most audiences took the poem more seriously than Frost intended, and Thomas similarly took it seriously and personally, and it provided the last straw in Thomas' decision to enlist.[9]

Thomas was promoted corporal, and in November 1916 was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant. He was killed in action soon after he arrived in France at Arras on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917. To spare the feelings of his widow Helen, she was told the fiction of a "bloodless death" i.e. that Thomas was killed by the concussive blast wave of one of the last shells fired as he stood to light his pipe and that there was no mark on his body.[10] However, a letter from his commanding officer Franklin Lushington written in 1936 (and discovered many years later in an American archive) states that in reality the cause of Thomas' death was due to being "shot clean through the chest".[11]

W. H. Davies was devastated by the death and his commemorative poem "Killed In Action (Edward Thomas)" was included in Davies's 1918 collection "Raptures".[4]

Thomas is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Agny in France (Row C, Grave 43).[12]

Personal life

Thomas was survived by his wife, Helen, their son Merfyn and their two daughters Bronwen and Myfanwy. After the war, Thomas's widow, Helen, wrote about her courtship and early married life with Edward in the autobiography As it Was (1926); later she added a second volume, World Without End (1931). Myfanwy later said that the books had been written by her mother as a form of therapy to help lift herself from the deep depression into which she had fallen following Thomas's death.

Helen's short memoir My Memory of W. H. Davies was published in 1973, after her own death. In 1988, Helen's writings were gathered into a book published under the title Under Storm's Wing, which included As It Was and World Without End as well as a selection of other short works by Helen and her daughter Myfanwy and six letters sent by Robert Frost to her husband.[13]

Commemorations

Thomas is commemorated in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, London, by memorial windows in the churches at Steep and at Eastbury in Berkshire and with a blue plaque at 14 Lansdowne Gardens in Stockwell, south London, where he was born.[14]

There is also a plaque dedicated to him at 113 Cowley Road, Oxford, where he lodged before entering Lincoln College.[15]

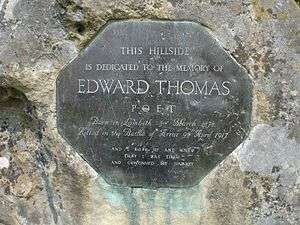

East Hampshire District Council have created a "literary walk" at Shoulder of Mutton Hill in Steep dedicated to Thomas,[16] which includes a memorial stone erected in 1935. The inscription includes the final line from one of his essays: "And I rose up and knew I was tired and I continued my journey."

As "Philip Edward Thomas poet-soldier" he is commemorated, alongside "Reginald Townsend Thomas actor-soldier died 1918", who is buried at the spot, and other family members, at the North East Surrey (Old Battersea) Cemetery.

He is the subject of the biographical play The Dark Earth and the Light Sky by Nick Dear, which premiered at the Almeida Theatre, London in November 2012, with Pip Carter as Thomas and Hattie Morahan as his wife Helen.[17]

In February 2013 his poem "Words" was chosen as the poem of the week by Carol Rumens in The Guardian[18]

Poetry

In Memoriam

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood

This Eastertide call into mind the men,

Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should

Have gathered them and will do never again.

- 6. IV. 15. 1915[19]

Thomas's poems are noted for their attention to the English countryside and a certain colloquial style. The short poem In Memoriam exemplifies how his poetry blends the themes of war and the countryside.

On 11 November 1985, Thomas was among 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey's Poet's Corner.[20] The inscription, written by fellow poet Wilfred Owen, reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."[21]

Thomas was described by British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes as "the father of us all."[22]

At least nineteen of his poems were set to music by the Gloucester composer Ivor Gurney.[23]

Selected works

Poetry collections

- Six Poems (under pseudonym Edward Eastaway) Pear Tree Press, 1916.

- Poems, Holt, 1917,[24] which included "The Sign-Post"[25]

- Last Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1918.

- Collected Poems, Selwyn & Blount, 1920.

- Two Poems, Ingpen & Grant, 1927.

- The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. R. George Thomas, Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Edward Thomas: A Mirror of England, ed. Elaine Wilson, Paul & Co., 1985.

- Edward Thomas: Selected Poems, ed. Ian Hamilton, Bloomsbury, 1995.

- The Poems of Edward Thomas, ed. Peter Sacks, Handsel Books, 2003.

- The Annotated Collected Poems, ed. Edna Longley, Bloodaxe Books, 2008.

Prose fiction

Prose

- In Pursuit of Spring (travel) Thomas Nelson and Sons, April 1914 [27]

Essays and collections

- Horae Solitariae, Dutton, 1902.

- Oxford, A & C Black, 1903.

- Beautiful Wales, Black, 1905.

- The Heart of England, Dutton, 1906.

- The South Country, Dutton, 1906 (reissued by Tuttle, 1993).

- Rest and Unrest, Dutton, 1910.

- Light and Twilight, Duckworth, 1911.

- The Icknield Way, Constable, 1913.

- The Last Sheaf, Jonathan Cape, 1928.

References to Thomas by other writers

- In 1918 W. H. Davies published his poem Killed In Action (Edward Thomas) to mark the personal loss of his close friend and mentor.[28]

- Many poems about Thomas by other poets can be found in the books Elected Friends: Poems For and About Edward Thomas, (1997, Enitharmon Press) edited by Anne Harvey, and Branch-Lines: Edward Thomas and Contemporary Poetry, (2007, Enitharmon Press) edited by Guy Cuthbertson and Lucy Newlyn.

- Norman Douglas considered Thomas handicapped in life through lacking "a little touch of bestiality, a little je-m'en-fous-t-ism. He was too scrupulous".[29]

- In his 1980 autobiography, Ways of Escape, Graham Greene references Thomas's poem "The Other" (about a man who seems to be following his own double from hotel to hotel) in describing his own experience of being bedeviled by an imposter.

- Edward Thomas's Collected Poems was one of Andrew Motion's ten picks for the poetry section of the "Guardian Essential Library" in October 2002.[30]

- In his 2002 novel Youth, J.M. Coetzee has his main character, intrigued by the survival of pre-modernist forms in British poetry, ask himself: "What happened to the ambitions of poets here in Britain? Have they not digested the news that Edward Thomas and his world are gone for ever?"[31] In contrast, Irish critic Edna Longley writes that Thomas's Lob, a 150-line poem, "strangely preempts The Waste Land through verses like: "This is tall Tom that bore / The logs in, and with Shakespeare in the hall / Once talked".[32]

- In his 1995 novel, Borrowed Time, the author Robert Goddard bases the home of the main character at Greenhayes in the village of Steep, where Thomas lived from 1913. Goddard weaves some of the feeling from Thomas's poems into the mood of the story and also uses some quotes from Thomas's works.

- Will Self's 2006 novel, The Book of Dave, has a quote from The South Country as the book's epigraph: "I like to think how easily Nature will absorb London as she absorbed the mastodon, setting her spiders to spin the winding sheet and her worms to fill in the graves, and her grass to cover it pitifully up, adding flowers — as an unknown hand added them to the grave of Nero."

- The children's author Linda Newbery has published a novel, "Lob" (David Fickling Books, 2010, illustrated by Pam Smy) inspired by the Edward Thomas' poem of the same name and containing oblique references to other work by him.

- Woolly Wolstenholme, formerly of UK rock band Barclay James Harvest, has used a humorous variation of Thomas' poem Adlestrop on the first song of his 2004 live album, Fiddling Meanly, where he imagines himself in a retirement home and remembers "the name" of the location where the album was recorded. The poem was read at Wolstenholme's funeral on 19 January 2011.

- Stuart Maconie in his book Adventures On The High Teas mentions Thomas and his poem "Adlestrop". Maconie visits the now abandoned and overgrown station which was closed by Beeching in 1966.[33]

- Robert MacFarlane, in his 2012 book The Old Ways, critiques Thomas and his poetry in the context of his own explorations of paths and walking as an analogue of human consciousness.[34]

- In his 2012 novel Sweet Tooth, Ian McEwan has a character invoke Thomas's poem "Adlestrop," as a "sweet, old-fashioned thing" and an example of "the sense of pure existence, of being suspended in space and time, a time before a cataclysmic war."[35]

- The last years of Thomas's life are explored in A Conscious Englishman, a 2013 biographical novel by Margaret Keeping, published by StreetBooks.

- Pat Barker's 1995 WW1 novel, The Ghost Road, Booker Prize winner and the third novel of her Regeneration Trilogy, has as its opening epigraph 4 lines from 'Roads'.

'Now all roads lead to France/ And heavy is the tread/ Of the living; but the dead/ Returning lightly dance:'

References

- ↑ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- 1 2 Abrams, MH (1986). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 1893. ISBN 0-393-95472-2.

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel, 'Die Freuden der Unordnung', Süddeutsche Zeitung nr 109 (13 May 2005), p. 16.

- 1 2 Stonesifer, R.J. (1963), W. H. Davies — A Critical Biography, London, Jonathan Cape. B0000CLPA3.

- ↑ "FDP – Visiting the Dymock Area". Dymockpoets.org.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jul/29/robert-frost-edward-thomas-poetry}

- ↑ "Dymock Poets Archive", Archives, UK: University of Gloucestershire

- ↑ Thomas, Edward, Adlestrop (poem), UK: Poets’ graves

- 1 2 Hollis, Matthew (29 July 2011). "Edward Thomas, Robert Frost and the road to war". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "France: First World War", Travel, London: The Daily Telegraph, 27 February 1999

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya. "Myth of war poet Edward Thomas' 'bloodless' death | Daily Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Casualty Details: Thomas, Philip Edward". Debt of Honour Register. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ Edna Longley, England and Other Women, London Review of Books, Edna Longley, 5 May 1988.

- ↑ The Vauxhall Society@vauxhallsociety (1917-04-09). "Edward Thomas". Vauxhallcivicsociety.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Cowley Road". Oxfordhistory.org.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Walking in East Hampshire, East Hampshire, UK: District Council

- ↑ "Almeida". Almeida. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Carol Rumens (23 February 2013). "Poem of the week: Words by Edward Thomas". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ First World War Digital Archive.

- ↑ "Poets", The Great War, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University

- ↑ "Preface", The Great War, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University

- ↑ The timeless landscape of Edward Thomas, UK: The Daily Telegraph

- ↑ "Composer: Ivor (Bertie) Gurney (1890–1937)". recmusic.org. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ "The Sign-post", at PoetryFoundation.org

- ↑ "The happy-go-lucky Morgans : Thomas, Edward, 1878–1917 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "In pursuit of spring : Thomas, Edward, 1878–1917 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ Davies, W.H. (1918), Forty New Poems, A.C. Fifield. ASIN: B000R2BQIG

- ↑ Norman Douglas, Looking Back (Chatto and Windus, 1934) p. 175

- ↑ Motion, Andrew (19 October 2002). "Guardian Essential Library: Poetry". Books to furnish a room... and enrich a mind. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ Coetzee, J. M. (2002). Youth. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 58. ISBN 0-436-20582-3.

- ↑ Longley, Edna (2005). "The Great War, history, and the English lyric". In Vincent Sherry (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 67.

- ↑ Stuart Maconie, 2009, Adventures On The High Teas, Stuart Maconie, Ebury Press, pp 239-242.

- ↑ Robert MacFarlane, 2012, The Old Ways, Robert MacFarlane, Hamish Hamilton, 2012, pp 333-355

- ↑ Ian McEwan, 2012, Sweet Tooth," Ian McEwan Nan A. Talese, 2012, pp 177-178

Additional sources

- Hollis, M., 2011, Now All Roads Lead to France: The Last Years of Edward Thomas, Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24598-7

Further reading

- Jean Moorcroft Wilson (2015), Edward Thomas: from Adlestrop to Arras; a biography, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-4081-8713-5

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edward Thomas |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Thomas (poet). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Thomas (poet) |

- Edward Thomas profile, Poets.org.

- Edward Thomas profile, Poetry Foundation.

- Works by Edward Thomas at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward Thomas at Internet Archive

- Works by Edward Thomas at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas, Edward, Works, Internet Archive.

- Edward Thomas Fellowship, UK: The Edward Thomas Fellowship.

- "Dymock Poets Archive", Archives and Special Collections, UK: University of Gloucestershire.

- Edward Thomas Archive at Cardiff University

- "The Edward Thomas Collection", The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, UK: Oxford University

- "Archival material relating to Edward Thomas". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Edward Thomas at the National Portrait Gallery, London