Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

| Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Nadar | |

| Born |

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc 27 January 1814 Paris, France |

| Died |

17 September 1879 (aged 65) Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Royal Gold Medal (1864) |

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (27 January 1814 – 17 September 1879) was a French architect and theorist, famous for his interpretive "restorations" of medieval buildings. Born in Paris, he was a major Gothic Revival architect.

His works were largely restorative and few of his independent building designs were ever realised. Strongly contrary to the prevailing Beaux-Arts architectural trend of his time, much of his design work was largely derided by his contemporaries. He was the architect hired to design the internal structure of the Statue of Liberty, but died before the project was completed.

Early years

Viollet-le-Duc's father was a civil servant living in Paris who collected books; his mother's Friday salons were attended by Stendhal and Sainte-Beuve. His mother's brother, Étienne-Jean Delécluze, "a painter in the mornings, a scholar in the evenings",[1] was largely in charge of the young man's education. Viollet-le-Duc was trendy philosophically: republican, anti-clerical, rebellious, he built a barricade in the July Revolution of 1830 and refused to enter the École des Beaux-Arts. Instead he opted in favor of direct practical experience in the architectural offices of Jacques-Marie Huvé and Achille Leclère.

Architectural restorer

Restoration work

During the early 1830s, a popular sentiment for the restoration of medieval buildings developed in France. Viollet-le-Duc, returning during 1835 from study in Italy, was commissioned by Prosper Mérimée to restore the Romanesque abbey of Vézelay. This work was the first of a long series of restorations; Viollet-le-Duc's restorations at Notre Dame de Paris with Jean-Baptiste Lassus brought him national attention. His other main works include Mont Saint-Michel, Carcassonne, Roquetaillade castle and Pierrefonds.

Viollet-le-Duc's "restorations" frequently combined historical fact with creative modification. For example, under his supervision, Notre Dame was not only cleaned and restored but also "updated", gaining its distinctive third tower (a type of flèche) in addition to other smaller changes. Another of his most famous restorations, the medieval fortified town of Carcassonne, was similarly enhanced, gaining atop each of its many wall towers a set of pointed roofs that are actually more typical of northern France. Many of these reconstructions were controversial. Viollet-le-duc wanted what he called ‘a condition of completeness' which never actually existed at any given time. This approach to restoration was particularly problematic when buildings survived in a mixture of styles. For instance, Viollet-le-Duc eliminated eighteenth-century additions to Notre Dame. Both his theory and his practice were strongly criticized on the grounds that only what had once been in place should be reconstructed.[2] At the same time, in the cultural atmosphere of the Second Empire theory necessarily became diluted in practice: Viollet-le-Duc provided a Gothic reliquary for the relic of the Crown of Thorns at Notre-Dame in 1862, and yet Napoleon III also commissioned designs for a luxuriously appointed railway carriage from Viollet-le-Duc, in 14th-century Gothic style.

Among his restorations were:

- Churches

- Basilica of St. Mary Magdalene in Vézelay

- St. Martin in Clamecy

- Notre-Dame in Paris

- Sainte-Chapelle in Paris (under Félix Duban)

- Basilica of St. Denis near Paris

- St. Louis in Poissy

- Notre-Dame in Semur-en-Auxois

- Basilica of St. Nazarius and St. Celsus in Carcasonne

- Basilica of St. Sernin in Toulouse

- Notre-Dame in Lausanne (Switzerland)

- Town halls

- Castles

- Château de Roquetaillade, in Bordeaux

- Château de Pierrefonds

- Fortified city of Carcassonne

- Château de Coucy

- Antoing in Belgium

- Château de Vincennes, Paris

Restoration of the Château de Pierrefonds, reinterpreted by Viollet-le-Duc for Napoleon III, was interrupted by the departure of the Emperor in 1870.

Restorations by Viollet-le-Duc

Abbey of la Madaleine, Vézelay (1840-1861)

Abbey of la Madaleine, Vézelay (1840-1861) Notre Dame de Paris (restored 1845-1870)

Notre Dame de Paris (restored 1845-1870) The keep of the Chateau de Vincennes, (restored in the 1860s)

The keep of the Chateau de Vincennes, (restored in the 1860s) The walled town of Carcasonne (restored 1853-1879)

The walled town of Carcasonne (restored 1853-1879) Chateau de Pierrefonds (restored 1857-1885)

Chateau de Pierrefonds (restored 1857-1885)- Lausanne Cathedral, Switzerland (Restored 1874-1910)

Influence on historic preservation

Basic intervention theories of historic preservation are framed in the dualism of the retention of the status quo versus a "restoration" that creates something that never actually existed in the past. John Ruskin was a strong proponent of the former sense, while his contemporary, Viollet-le-Duc, advocated for the latter instance. Viollet-le-Duc wrote that restoration is a "means to reestablish [a building] to a finished state, which may in fact never have actually existed at any given time."[3] The type of restoration employed by Viollet-le-Duc, in its English form as Victorian restoration, was decried by Ruskin as "a destruction out of which no remnants can be gathered: a destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed."[4]

This argument is still a current one when restoration is being considered for a building or landscape. In removing layers of history from a building, information and age value are also removed which can never be recreated. However, adding features to a building, as Viollet-le-Duc also did, can be more appealing to modern viewers.

Publications

Throughout his career Viollet-le-Duc made notes and drawings, not only for the buildings he was working on, but also on Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance buildings that were to be soon demolished. His notes were helpful in his published works. His study of medieval and Renaissance periods was not limited to architecture, but extended to furniture, clothing, musical instruments, armament, geology and so forth.

All this work was published, first in serial, and then as full-scale books, as:

- Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th Century (1854–1868) (Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle) - Original (French) language edition, including numerous illustrations.

- Dictionary of French Furnishings (1858–1870) (Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque Carolingienne à la Renaissance.)

- Entretiens sur l'architecture (in 2 volumes, 1863–72), in which Viollet-le-Duc systematized his approach to architecture and architectural education, in a system radically opposed to that of the École des Beaux-Arts, which he had avoided in his youth and despised. In Henry Van Brunt's translation, the "Discourses on Architecture" was published in 1875, making it available to an American audience little more than a decade after its initial publication in France.

- Histoire de l'habitation humaine, depuis les temps préhistoriques jusqu'à nos jours (1875). Published in English in 1876 as Habitations of Man in All Ages. Viollet-Le-Duc traces the history of domestic architecture among the different "races" of mankind.

- L'art russe: ses origines, ses éléments constructifs, son apogée, son avenir (1877), where Viollet-le-Duc applied his ideas of rational construction to Russian architecture.

Architectural theory and new building projects

Viollet-le-Duc is considered by many to be the first theorist of modern architecture. Sir John Summerson wrote that "there have been two supremely eminent theorists in the history of European architecture - Leon Battista Alberti and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc."[1]

His architectural theory was largely based on finding the ideal forms for specific materials, and using these forms to create buildings. His writings centered on the idea that materials should be used 'honestly'. He believed that the outward appearance of a building should reflect the rational construction of the building. In Entretiens sur l'architecture, Viollet-le-Duc praised the Greek temple for its rational representation of its construction. For him, "Greek architecture served as a model for the correspondence of structure and appearance."[5] There is speculation that this philosophy was heavily influenced by the writings of John Ruskin, who championed honesty of materials as one of the seven main emphases of architecture.

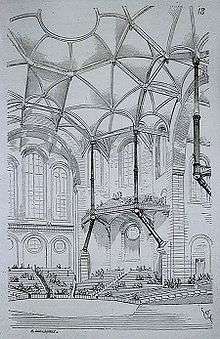

In several unbuilt projects for new buildings, Viollet-le-Duc applied the lessons he had derived from Gothic architecture, applying its rational structural systems to modern building materials such as cast iron. He also examined organic structures, such as leaves and animal skeletons, for inspiration. He was especially interested in the wings of bats, an influence represented by his Assembly Hall project.

Viollet-le-Duc's drawings of iron trusswork were innovative for the time. Many of his designs emphasizing iron would later influence the Art Nouveau movement, most noticeably in the work of Hector Guimard, Victor Horta, Antoni Gaudí or Hendrik Petrus Berlage. His writings inspired some American architects, including Frank Furness, John Wellborn Root, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright.[6]

Military career and influence

Viollet-le-Duc had a second career in the military, primarily in the defence of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). He was so influenced by the conflict that during his later years he described the idealized defense of France by the analogy of the military history of Le Roche-Pont, an imaginary castle, in his work Histoire d'une Forteresse (Annals of a Fortress, twice translated into English). Accessible and well researched, it is partly fictional.

Annals of a Fortress strongly influenced French military defensive thinking. Viollet-le-Duc's critique of the effect of artillery (applying his practical knowledge from the 1870–1871 war) is so complete that it accurately describes the principles applied to the defence of France until World War II. The physical results of his theories are present in the fortification of Verdun prior to World War I and the Maginot Line prior to World War II. His theories are also represented by the French military theory of "Deliberate Advance", such that artillery and a strong system of fortresses in the rear of an army are essential.

Legacy

Some of his restorations, such as that of the Château de Pierrefonds, have become very controversial because they were not intended so much to recreate a historical situation accurately as to create a "perfect building" of medieval style: "to restore an edifice", he observed in the Dictionnaire raisonné, "is not to maintain it, repair or rebuild it, but to re-establish it in a complete state that may never have existed at a particular moment".[7] The idea and the very word restoration applied to architecture Viollet-le-Duc considered part of a modern innovation. Modern conservation practice considers Viollet-le-Duc's restorations too free, too personal, too interpretive, but some of the monuments he restored might have been lost otherwise.

The English architect Benjamin Bucknall (1833–95) was a devotee of Viollet-le-Duc and during 1874 to 1881 translated several of his publications into English to popularise his principles in Great Britain. The later works of the English designer and architect William Burges were greatly influenced by Viollet-le-Duc, most strongly in Burges's designs for his own home, The Tower House in London's Holland Park district and Burges's designs for Castell Coch near Cardiff, Wales.[8]

An exhibition, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc 1814–1879 was presented in Paris, 1965, and a larger, centennial exhibition, 1980.

Viollet-le-Duc was the subject of a Google Doodle on January 27, 2014.[9]

Later life

In 1874 Viollet-le-Duc resigned as diocesan architect of Paris, and was succeeded by his contemporary, Paul Abadie.[10] In his old age, Viollet-le-Duc relocated to Lausanne, Switzerland, where he constructed a villa (since destroyed). He died there in 1879.

The writer Geneviève Viollet-le-Duc (winner of the prix Broquette-Gonin in 1978) was his great granddaughter.

Notes

- 1 2 Summerson, Sir John (1948). Heavenly Mansions and Other essays on Architecture. London: Cresset Press.

- ↑ Burke, Peter (2013). A Social History of Knowledge II: From the Encyclopaedia to Wikipedia. Wiley. ISBN 978-0745650432.

- ↑ Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. ([1854] 1990). The foundations of architecture. New York: George Braziller. P. 195. (Translated by Kenneth D. Whitehead from the original French.)

- ↑ John Ruskin. ([1880] 1989). The seven lamps of architecture. New York: Dover Publications. P. 194

- ↑ Ochshorn, Jonathan. "Designing Building Failures". Cornell University.

- ↑ Viollet-Le-Duc, Eugene-Emmanuel (1990). The Architectural Theory of Viollet-Le-Duc: Readings and Commentary. MIT Press.

- ↑ "Restaurer un édifice, ce n'est pas l'entretenir, le reparer ou le refaire, c'est le rétablir dans un état complet qui ne peut avoir jamais existé à un moment donné". (Dictionnaire raisonné, s.v. "Restauration")

- ↑ "Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington". British History Online. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ "Eugène Viollet-le-Duc's 200th birthday: Architect celebrated in Google doodle". The Independent. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ jpd. "Paul Abadie, architecte". Histoire-vesinet.org. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

References

External links

Works related to Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to 16th Century at Wikisource

Works related to Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to 16th Century at Wikisource Media related to Viollet-le-Duc at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Viollet-le-Duc at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eugène Viollet-le-Duc at Internet Archive

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène Emmanuel". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène Emmanuel". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.