Eurasian collared dove

| Eurasian collared dove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Streptopelia decaocto

Call | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Streptopelia |

| Species: | S. decaocto |

| Binomial name | |

| Streptopelia decaocto (Frivaldszky, 1838) | |

| |

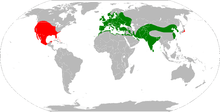

The Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto), most often simply called the collared dove,[2][3][4][5] also sometimes hyphenated as Eurasian collared-dove,[6] is a species of dove native to warm temperate and subtropical Asia, and introduced in North America in the 1980s.

The genus name Streptopelia is from Ancient Greek streptos, "collar" and peleia, "dove". The specific decaocto is a latinisation of the Greek word for "eighteen", from deca, "ten", and octo, "eight". In Greek mythology, a servant complained bitterly about pay of just 18 pieces a year, and the gods changed her to a dove that still cries mournfully.[7]

Description

It is a medium-sized dove, distinctly smaller than the wood pigeon, similar in length to a rock pigeon but slimmer and longer-tailed, and slightly larger than the related turtle dove, with an average length of 32 cm (13 in)[8] from tip of beak to tip of tail, with a wingspan of 47–55 cm (19–22 in), and a weight of 125–240 g (4.4–8.5 oz). It is grey-buff to pinkish-grey overall, a little darker above than below, with a blue-grey under wing patch. The tail feathers are grey-buff above, and dark grey tipped white below; the outer tail feathers also tipped whitish above. It has a black half-collar edged with white on its nape from which it gets its name. The short legs are red and the bill is black. The iris is red, but from a distance the eyes appear to be black, as the pupil is relatively large and only a narrow rim of reddish-brown iris can be seen around the black pupil. The eye is surrounded by a small area of bare skin, which is either white or yellow. The two sexes are virtually indistinguishable; juveniles differ in having a poorly developed collar, and a brown iris.[2][4][5]

There are two subspecies, Streptopelia decaocto decaocto in most of the range (including all of the 20th century colonisations), and Streptopelia decaocto xanthocyclus in the southeast of the range from Burma east to southern China. The latter differs in having yellow skin around the eye (white in the nominate subspecies).[6] Two other subspecies formerly sometimes accepted, Streptopelia decaocto stoliczkae from Turkestan in central Asia, and Streptopelia decaocto intercedens from southern India and Sri Lanka,[4] are now considered synonyms of S. d. decaocto.[6]

It is closely related to the island collared dove of southeast Asia and the African collared dove of sub-Saharan Africa, forming a superspecies with these.[6] Identification from African collared dove is very difficult with silent birds, with the African species being marginally smaller and paler, but the calls are very distinct, a soft purring in African collared dove quite unlike the Eurasian collared dove's cooing.[2]

Distribution

The collared dove is not migratory, but is strongly dispersive. Over the last century, it has been one of the great colonisers of the bird world. Its original range at the end of the 19th century was warm temperate and subtropical Asia from Turkey east to southern China and south through India to Sri Lanka. In 1838 it was reported in Bulgaria, but not until the 20th century did it expand across Europe, appearing in parts of the Balkans between 1900–1920, and then spreading rapidly northwest, reaching Germany in 1945, Great Britain by 1953 (breeding for the first time in 1956), Ireland in 1959, and the Faroe Islands in the early 1970s. Subsequent spread was 'sideways' from this fast northwest spread, reaching northeast to north of the Arctic Circle in Norway and east to the Ural Mountains in Russia, and southwest to the Canary Islands and northern Africa from Morocco to Egypt, by the end of the 20th century. In the east of its range, it has also spread northeast to most of central and northern China, and locally (probably introduced) in Japan.[2][3][4][6] It has also reached Iceland as a vagrant (41 records up to 2006), but has not colonised successfully there.[9]

Invasive status in North America

In 1974, less than 50 Eurasian Collared Doves escaped captivity in Nassau, New Providence, Bahamas.[10] From the Bahamas, the species spread to Florida, and is now found in nearly every state in the US, as well as in Mexico.[11][12] In Arkansas (United States), the species was recorded first in 1989 and since then has grown in numbers and is now present in 42 of 75 counties in the state. It spread from the southeast corner of the state in 1997 to the northwest corner in 5 years, covering a distance of about 500 km (310 mi) at a rate of 100 km (62 mi) per year.[13] This is more than double the rate of 45 km (28 mi) per year observed in Europe.[14] Interestingly, as of 2012, few negative impacts have been demonstrated in Florida, where the species is most prolific.[15][16] However, the species is known as an aggressive competitor, and there is concern that as populations continue to grow, native birds will be outcompeted by the invaders.[15] However, one study found that Eurasian collared doves are not more aggressive or competitive than native mourning doves, despite similar dietary preferences.[17]

Population growth has ceased in areas where they’ve been established the longest, such as Florida, but is still growing exponentially in areas of more recent introduction.[18] Carrying capacities appear to be highest in areas with higher temperatures and intermediate levels of development, such as suburban areas and some agricultural areas.[18]

While the spread of disease to native species has not been recorded in a study, Eurasian Collared Doves are known carriers of the parasite Trichomonas gallinae as well as Pigeon Paramyxovirus.[11][15] Both Trichomonas gallinae and Pigeon Paramyxovirus can spread to native birds via commingling at feeders and by consumption of doves by predators. Pigeon Paramyxovirus is an emergent disease and has the potential to affect domestic poultry, making the Eurasian Collared Dove a threat to not only native biodiversity, but a possible economic threat as well.[11]

Behaviour

.jpg)

Collared doves typically breed close to human habitation wherever food resources are abundant and there are trees for nesting; almost all nests are within 1 km (0.62 mi) of inhabited buildings. The female lays two white eggs in a stick nest, which she incubates during the night and which the male incubates during the day. Incubation lasts between 14 and 18 days, with the young fledging after 15 to 19 days. Breeding occurs throughout the year when abundant food is available, though only rarely in winter in areas with cold winters such as northeastern Europe. Three to four broods per year is common, although up to six broods in a year has been recorded.[4] Eurasian Collared Doves are a monogamous species, and share parental duties when caring for young.[19]

The male's mating display is a ritual flight, which, as with many other pigeons, consists of a rapid, near-vertical climb to height followed by a long glide downward in a circle, with the wings held below the body in an inverted "V" shape. At all other times, flight is typically direct using fast and clipped wing beats and without use of gliding.

The collared dove is not wary and often feeds very close to human habitation, including visiting bird tables; the largest populations are typically found around farms where spilt grain is frequent around grain stores or where livestock are fed. It is a gregarious species and sizeable winter flocks will form where there are food supplies such as grain (its main food) as well as seeds, shoots and insects. Flocks most commonly number between ten and fifty, but flocks of up to ten thousand have been recorded.[4]

The song is a coo-COO-coo. The collared dove also makes a harsh loud screeching call lasting about two seconds, particularly in flight just before landing. A rough way to describe the screeching sound is a hah-hah.

Collared doves cooing in early spring are sometimes mistakenly reported as the calls of early-arriving cuckoos and, as such, a mistaken sign of spring's return.[4]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Streptopelia decaocto". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 3 4 Snow, D. W.; Perrins, C. M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic (Concise ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- 1 2 Hagemeijer, W. J. M., & Blair, M. J., eds. (1997). The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds. Poyser, London ISBN 0-85661-091-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cramp, S., ed. (1985). The Birds of the Western Palearctic 4: 340-353. ISBN 978-0-19-857507-8

- 1 2 Javier Blasco-Zumeta, Laboratorio Virtual Ibercaja Collared Dove

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoyo, J. del; et al., eds. (1997). Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 4. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 137. ISBN 84-87334-22-9.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 131, 367. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Campbell, Donald (2000). "Collared Dove". The Encyclopedia of British Birds. Bath: Parragon. p. 95. ISBN 0752541595.

- ↑ Birding Iceland: Eurasian Collared Dove

- ↑ Hengeveld, R (Autumn 1993). "What to Do about the North American Invasion by the Collared Dove?". Journal of Field Ornithology. 64 (4): 477–489. JSTOR 4513859.

- 1 2 3 Schuler, Krysten; Green, David; Justice-Allen, Anne; Jaffe, Rosemary; Cunningham, Mark; Thomas, Nancy; Spalding, Marilyn; Ip, Hon (June 2012). "Expansion of an Exotic Species and Concomitant Disease Outbreaks: Pigeon Paramyoxovirus in Free-Ranging Eurasian Collared Doves". EcoHealth. 9 (2): 163–170. doi:10.1007/s10393-012-0758-6. PMID 22476688.

- ↑ Almazán-Núñez, R. C. (2014). "Nuevos registros de la paloma turca (Streptopelia decaocto) en el estado de Guerrero, México". Acta Zoológica Mexicana. 30 (3): 701–706.

- ↑ Fielder, J. M., R. Kannan, D. A. James, and J. C. Cunningham (2012). Status, dispersal, and breeding biology of the exotic Eurasian Collared-dove (Streptopelia decaocto) in Arkansas. J. Arkansas Academy of Science 66: 55-61.

- ↑ Hengeveld, R. (1988). Mechanisms of biological invasions. J. of Biogeography 15:819-828.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Steve; Donaldson-Fortier, Gay. "Florida's Introduced Birds: Eurasian Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto)". University of Florida IFAS Extension. Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation: University of Florida. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Bonter, David N., Benjamin Zuckerberg, and Janis L. Dickinson. "Invasive Birds in a Novel Landscape: Habitat Associations and Effects on Established Species." Ecography 33 (2010): 494-502. Project Feeder Watch. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ↑ Poling, Trisha D., and Steven E. Hayslette. "Dietary Overlap and Foraging Competition Between Mourning Doves and Eurasian Collared-Doves." Journal of Wildlife Management 70.4 (2006): 998-1004.

- 1 2 Scheidt SN, Hurlbert AH (2014) Range Expansion and Population Dynamics of an Invasive Species: The Eurasian Collared-Dove (Streptopelia decaocto). PLoS ONE 9(10): e111510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111510

- ↑ Hirschenhauser, Katharina; Winkler, Hans; Oliveira, Rui F. (2003). "Comparative analysis of male androgen responsiveness to social environment in birds: the effects of mating system and paternal incubation". Hormones and Behavior. 43 (4): 508–519. doi:10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00027-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eurasian Collared Dove. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Streptopelia decaocto |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 4.6 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- "Eurasian Collared-dove media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Eurasian Collared-dove photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Streptopelia decaocto at IUCN Red List maps