Eurofighter Typhoon

| Eurofighter Typhoon | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Eurofighter Typhoon of the Royal Saudi Air Force over Malta in 2010 | |

| Role | Multirole fighter |

| National origin | Multi-national |

| Manufacturer | Eurofighter Jagdflugzeug GmbH |

| First flight | 27 March 1994[1] |

| Introduction | 4 August 2003 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force German Air Force Italian Air Force Spanish Air Force See Operators below for others |

| Produced | 1994–present |

| Number built | 487 (October 2016)[2][3][4][5] |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed from | British Aerospace EAP |

| Variants | Eurofighter Typhoon variants |

The Eurofighter Typhoon is a twin-engine, canard-delta wing, multirole fighter.[8][9] The Typhoon was designed and is manufactured by a consortium of Alenia Aermacchi, Airbus Group and BAE Systems that conducts the majority of the project through a joint holding company, Eurofighter Jagdflugzeug GmbH formed in 1986. NATO Eurofighter and Tornado Management Agency manages the project and is the prime customer.[10]

The aircraft's development effectively began in 1983 with the Future European Fighter Aircraft programme, a multinational collaboration among the UK, Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Disagreements over design authority and operational requirements led France to leave the consortium to develop the Dassault Rafale independently. A technology demonstration aircraft, the British Aerospace EAP, first took flight on 6 August 1986; the first prototype of the finalised Eurofighter made its first flight on 27 March 1994. The aircraft's name, Typhoon, was adopted in September 1998; the first production contracts were also signed that year.

Political issues in the partner nations significantly protracted the Typhoon's development; the sudden end of the Cold War reduced European demand for fighter aircraft, and there was debate over the aircraft's cost and work share. The Typhoon entered operational service in 2003; it has entered service with the Austrian Air Force, the Italian Air Force, the German Air Force, the Royal Air Force, the Spanish Air Force, and the Royal Saudi Air Force. The Royal Air Force of Oman and the Kuwait Air Force are export customers, bringing the procurement total to 599 aircraft as of 2016.

The Eurofighter Typhoon is a highly agile aircraft, designed to be a supremely effective dogfighter in combat.[11] Later production aircraft have been increasingly better equipped to undertake air-to-surface strike missions and to be compatible with an increasing number of different armaments and equipment including Storm Shadow and the RAF's Brimstone. The Typhoon saw its combat debut during the 2011 military intervention in Libya with the Royal Air Force and the Italian Air Force, performing aerial reconnaissance and ground strike missions. The type has also taken primary responsibility for air-defence duties for the majority of customer nations.

Development

Origins

The UK had identified a requirement for a new fighter as early as 1971. The AST 403 specification, issued by the Air staff in 1972, led to the P.96 conventional "tailed" design presented in the late 1970s. While the design would have met the Air Staff's requirements, the UK air industry had reservations, as it appeared to be very similar to the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, which was then well advanced in its development. The P.96 design had little potential for growth, and when it entered production, it would secure few exports in a market in which the Hornet would be well established.[12] However, the simultaneous West German requirement for a new fighter had led by 1979 to the development of the TKF-90 concept.[13][14] This was a cranked delta wing design with forward close-coupled-canard controls and artificial stability. Although the British Aerospace designers rejected some of its advanced features such as engine vectoring nozzles and vented trailing edge controls,[15] a form of boundary layer control, they agreed with the overall configuration.

In 1979, Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) and British Aerospace (BAe) presented a formal proposal to their respective governments for the ECF, the European Collaborative Fighter[16] or European Combat Fighter.[14] In October 1979 Dassault joined the ECF team for a tri-national study, which became known as the European Combat Aircraft.[16] It was at this stage of development the Eurofighter name was first attached to the aircraft.[17] The development of different national prototypes continued. France produced the ACX. The UK produced two designs; the P.106[N 1] was a single-engined "lightweight" fighter, superficially resembling the JAS 39 Gripen, the P.110 was a twin-engined fighter. The RAF rejected the P.106 concept on the grounds it had "half the effectiveness of the two-engined aircraft at two-thirds of the cost".[12] West Germany continued to refine the TKF-90 concept.[14] The ECA project collapsed in 1981 for several reasons, including differing requirements, Dassault's insistence on "design leadership" and the British preference for a new version of the RB199 to power the aircraft versus the French preference for the new Snecma M88.[17]

Consequently, the Panavia partners (MBB, BAe and Aeritalia) launched the Agile Combat Aircraft (ACA) programme in April 1982.[19] The ACA was very similar to the BAe P.110, having a cranked delta wing, canards and a twin tail. One major external difference was the replacement of the side-mounted engine intakes with a chin intake. The ACA was to be powered by a modified version of the RB199. The German and Italian governments withdrew funding, and the UK Ministry of Defence agreed to fund 50% of the cost with the remaining 50% to be provided by industry. MBB and Aeritalia signed up with the aim of producing two aircraft, one at Warton and one by MBB. In May 1983, BAe announced a contract with the MoD for the development and production of an ACA demonstrator, the Experimental Aircraft Programme.[19][20]

In 1983, Italy, Germany, France, the UK and Spain launched the "Future European Fighter Aircraft" (FEFA) programme. The aircraft was to have short take off and landing (STOL) and beyond visual range (BVR) capabilities. In 1984, France reiterated its requirement for a carrier-capable version and demanded a leading role. Italy, West Germany and the UK opted out and established a new EFA programme.[14] In Turin on 2 August 1985, West Germany, the UK and Italy agreed to go ahead with the Eurofighter; and confirmed France, along with Spain, had chosen not to proceed as a member of the project.[21] Despite pressure from France, Spain rejoined the Eurofighter project in early September 1985.[22] France officially withdrew from the project to pursue its own ACX project, which was to become the Dassault Rafale.

By 1986, the programme's cost had reached £180 million.[23] When the EAP programme had started, the cost was supposed to be equally shared by government and industry, but the West German and Italian governments wavered on the agreement and the three main industrial partners had to provide £100 million to keep the programme from ending. In April 1986, the BAe EAP was rolled out at BAe Warton, by this time also partially funded by MBB, BAe and Aeritalia.[23] The EAP first flew on 6 August 1986.[24] The Eurofighter bears a strong resemblance to the EAP. Design work continued over the next five years using data from the EAP. Initial requirements were: UK: 250 aircraft, Germany: 250, Italy: 165 and Spain: 100. The share of the production work was divided among the countries in proportion to their projected procurement – DASA (33%), British Aerospace (33%), Aeritalia (21%), and Construcciones Aeronáuticas SA (CASA) (13%).

The Munich-based Eurofighter Jagdflugzeug GmbH was established in 1986 to manage development of the project[25] and EuroJet Turbo GmbH, the alliance of Rolls-Royce, MTU Aero Engines, FiatAvio (now Avio) and ITP for development of the EJ200. The aircraft was known as Eurofighter EFA from the late 1980s until it was renamed EF 2000 in 1992.[26]

By 1990, the selection of the aircraft's radar had become a major stumbling-block. The UK, Italy and Spain supported the Ferranti Defence Systems-led ECR-90, while Germany preferred the APG-65-based MSD2000 (a collaboration between Hughes, AEG and GEC-Marconi). An agreement was reached after UK Defence Secretary Tom King assured his West German counterpart Gerhard Stoltenberg that the British government would approve the project and allow the GEC subsidiary Marconi Electronic Systems to acquire Ferranti Defence Systems from its parent, the Ferranti Group, which was in financial and legal difficulties. GEC thus withdrew its support for the MSD2000.[27]

Delays

The financial burdens placed on Germany by reunification caused Helmut Kohl to make an election promise to cancel the Eurofighter. In early to mid-1991 German Defence Minister Volker Rühe sought to withdraw Germany from the project in favour of using Eurofighter technology in a cheaper, lighter plane. Because of the amount of money already spent on development, the number of jobs dependent on the project, and the binding commitments on each partner government, Helmut Kohl was unable to withdraw; "Rühe's predecessors had locked themselves into the project by a punitive penalty system of their own devising."[28]

In 1995 concerns over workshare appeared. Since the formation of Eurofighter the workshare split had been agreed at 33/33/21/13 (United Kingdom/Germany/Italy/Spain) based on the number of units being ordered by each contributing nation, all the nations then reduced their orders. The UK cut its orders from 250 to 232, Germany from 250 to 140, Italy from 165 to 121 and Spain from 100 to 87.[28] According to these order levels the workshare split should have been 39/24/22/15 UK/Germany/Italy/Spain, Germany was unwilling to give up such a large amount of work.[28] In January 1996, after much negotiation between German and UK partners, a compromise was reached whereby Germany would purchase another 40 aircraft.[28] The workshare split was 43% for EADS MAS in Germany and Spain; 37.5% BAE Systems in the UK; and 19.5% for Alenia in Italy.[29]

The next major milestone came at the Farnborough Airshow in September 1996. The UK announced the funding for the construction phase of the project. In November 1996 Spain confirmed its order but Germany delayed its decision. After much diplomatic activity between Germany and the UK, an interim funding arrangement of DM100 million (€51 million) was contributed by the German government in July 1997 to continue flight trials. Further negotiations finally resulted in Germany's approval to purchase the Eurofighter in October 1997.

Testing

The maiden flight of the Eurofighter prototype took place in Bavaria on 27 March 1994, flown by DASA chief test pilot Peter Weger.[1] On 9 December 2004, Eurofighter Typhoon IPA4 began three months of Cold Environmental Trials (CET) at the Vidsel Air Base in Sweden, the purpose of which was to verify the operational behaviour of the aircraft and its systems in temperatures between −25 and 31 °C.[30] The maiden flight of Instrumented Production Aircraft 7 (IPA7), the first fully equipped Tranche 2 aircraft, took place from EADS' Manching airfield on 16 January 2008.[31]

Procurement, production and costs

The first production contract was signed on 30 January 1998 between Eurofighter GmbH, Eurojet and NETMA.[32] The procurement totals were as follows: the UK 232, Germany 180, Italy 121, and Spain 87. Production was again allotted according to procurement: British Aerospace (37.42%), DASA (29.03%), Aeritalia (19.52%), and CASA (14.03%).

On 2 September 1998, a naming ceremony was held at Farnborough, United Kingdom. This saw the Typhoon name formally adopted, initially for export aircraft only. The name continues the storm theme started by the Panavia Tornado. This was reportedly resisted by Germany, perhaps because the Hawker Typhoon was a fighter-bomber aircraft used by the RAF during the Second World War to attack German targets.[33] The name "Spitfire II" (after the famous British Second World War fighter, the Supermarine Spitfire) had also been considered and rejected for the same reason early in the development programme. In September 1998, contracts were signed for production of 148 Tranche 1 aircraft and procurement of long lead-time items for Tranche 2 aircraft.[34] In March 2008, the final aircraft out of Tranche 1 was delivered to the German Air Force, with all successive deliveries being at the Tranche 2 standard.[35] On 21 October 2008, the first two of 91 Tranche 2 aircraft, ordered four years before, were delivered to RAF Coningsby.[36]

In October 2008, the Eurofighter nations were considering splitting the 236-fighter Tranche 3 into two parts.[37] In June 2009, RAF Air Chief Marshal Sir Glenn Torpy suggested that the RAF fleet might only be 123 jets, instead of the 232 previously planned.[38] In spite of this reduction in required aircraft, on 14 May 2009 British Prime Minister Gordon Brown confirmed the UK would move ahead with the third batch purchase. A contract for the first part, Tranche 3A, was signed at the end of July 2009 for 112 aircraft split across the four partner nations, including 40 aircraft for the UK, 31 for Germany, 21 for Italy and 20 for Spain.[39][40] These 40 aircraft were said to have fully covered the UK's obligations in the project by Air Commodore Chris Bushell, because of cost overruns in the project.[41]

The Eurofighter Typhoon is unique in modern combat aircraft in that there are four separate assembly lines. Each partner company assembles its own national aircraft, but builds the same parts for all aircraft (including exports); Premium AEROTEC (main centre fuselage[42]), EADS CASA (right wing, leading edge slats), BAE Systems (front fuselage (including foreplanes), canopy, dorsal spine, tail fin, inboard flaperons, rear fuselage section) and Alenia Aermacchi (left wing, outboard flaperons, rear fuselage sections).

Production is divided into three tranches (see table below). Tranches are a production/funding distinction, and do not imply an incremental increase in capability with each tranche. Tranche 3 will most likely be based on late Tranche 2 aircraft with improvements added. Tranche 3 has been split into A and B parts.[40] Tranches are further divided up into production standard/capability blocks and funding/procurement batches, though these do not coincide, and are not the same thing; e.g., the Eurofighter designated FGR4 by the RAF is a Tranche 1, block 5. Batch 1 covered block 1, but batch 2 covered blocks 2, 2B and 5. On 25 May 2011 the 100th production aircraft, ZK315, rolled off the production line at Warton.[43]

| Tranche | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranche 1 | 15[N 2] | 33 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 53 | 148 |

| Tranche 2[44] | 0 | 79 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 34 | 67[N 3] | 275 |

| Tranche 3A[40] | 0 | 31 | 21 | 28 | 12 | 24 | 20 | 40 | 176 |

| Total | 15 | 143 | 96 | 28 | 12 | 72 | 73 | 160 | 599 |

In 1988, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Armed Forces told the UK House of Commons that the European Fighter Aircraft would "be a major project, costing the United Kingdom about £7 billion".[46] It was soon apparent a more realistic estimate was £13 billion,[47] made up of £3.3 billion development costs[48] plus £30 million per aircraft.[49] By 1997 the estimated cost was £17 billion; by 2003, £20 billion, and the in-service date (2003, defined as the date of delivery of the first aircraft to the RAF) was 54 months late.[50][51] After 2003, the Ministry of Defence refused to release updated cost-estimates on the grounds of 'commercial sensitivity'.[52] However, in 2011, the National Audit Office estimated the UK's "assessment, development, production and upgrade costs eventually hit £22.9 billion".[53]

By 2007, Germany estimated the system cost (aircraft and training, plus spare parts) at 120 million euros and said it was in perpetual increase.[54] On 17 June 2009, Germany ordered 31 aircraft of Tranche 3A for 2,800 million euros, leading to a system cost of 90 million euros per aircraft.[6] The UK's Committee of Public Accounts reported that the mismanagement of the project had helped increase the cost of each aircraft by 75 percent. Defence Secretary Liam Fox responded that "I am determined that in the future such projects are properly run from the outset, and I have announced reforms to reduce equipment delays and cost overruns."[55] The Spanish MoD put the cost of their Typhoon project up to December 2010 at 11.718 billion euros, up from an original 9.255 billion euros and implying a system cost for their 73 aircraft of 160 million euros.[56]

On 11 September 2008, the combined flying time of the five customer Air Forces and the industrial Flight Test programme saw the aircraft pass the 50,000 flight hours milestone.[57] On 31 March 2009, a Eurofighter Typhoon fired an AMRAAM whilst having its radar in passive mode for the first time; the necessary target data for the missile was acquired by the radar of a second Eurofighter Typhoon and transmitted using the Multi Functional Information Distribution System (MIDS).[58] In January 2011, the entire Typhoon fleet passed the 100,000 flying hours mark.[59] In September 2013, the worldwide Eurofighter fleet achieved over 200,000 flight hours. As of July 2016, a total of 599 orders have been received with 478 delivered.[60]

Upgrades

In 2000, the UK selected the MBDA Meteor as the long range air-to-air missile armament for her Typhoons with an in-service date (ISD) of December 2011.[61] In December 2002, France, Germany, Spain and Sweden joined the British in a $1.9bn contract for Meteor on Typhoon, the Dassault Rafale and the Saab Gripen.[61] The protracted contract negotiations pushed the ISD to August 2012,[61] and it was further put back by Eurofighter's failure to make trials aircraft available to the Meteor partners.[62] Meteor is now in production and first deliveries to the RAF were scheduled for Q4 2012[63] but full clearance on Typhoon is not planned until mid-2016.[64] While the Meteor may have been delivered, it will not enter service before 2016. In 2014 the "second element of the Phase 1 Enhancements package known as 'P1Eb'" was announced, allowing "Typhoon to realise both its air-to-air and air-to-ground capability to full effect".[65]

Budgetary pressures being encountered by the four original partner nations have limited upgrades [66] None of the partner nations have confirmed an order for Tranche 3Bs, which would have been "optimized for future higher-tempo air-to-air and strike operations", and Germany has cut its own orders short to avoid the model.[67] Furthermore, the four original partner nations have proved reluctant to collectively fund enhancements that extend the aircraft’s air-to-ground capability, such as integration of the MBDA Storm Shadow cruise missile. [68]

However the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force has an enhancement programme that aims to integrate the MBDA Storm Shadow cruise missile, the MBDA Brimstone air-to-surface missile and the Meteor Beyond Visual Range Air-to-Air Missile into its Eurofighter Typhoon force. [69][70][71] This programme is known as Project Centurion and has set a target of December 2018 to seamlessly integrate the weapons and capability of the Panavia Tornado GR4 fleet before they go out of service in 2019. [72][73][74] In October 2016, BAE systems confirmed that the first phase of Project Centurion's package of enhancements had entered the operational evaluation stage.[75][76]

Tranche 3 aircraft ESM/ECM enhancements have been focused on improving radiating jamming power with antenna modifications, while EuroDASS is reported to offer a range of new capabilities, including the addition of a digital receiver, extending band coverage to low frequencies (VHF/UHF) and introducing an interferometric receiver with extremely precise geolocation functionalities. On the jamming side, EuroDASS is looking to low-band[77] (VHF/UHF) jamming, more capable antennae, new ECM techniques, while protection against missile, is to be enhanced through a new passive MWS in addition to the active devices already on board the aircraft. The latest support for self-protection will however originate from the new aesa radar which is to replace the Captor system, providing in a spiralled programme with passive, active and cyberwarfare RF capabilities.

Selex ES has developed a self-contained expendable Digital Radio Frequency Memory (DRFM) jammer for fast jet aircraft known as the BriteCloud, which was expected to be available on the market by mid-2014. It will provide an off-board capability to decoy RF guided missile seekers and fire control radars, producing large miss distance and angle break lock, thanks to self-contained coherent technique generation processing and high-power batteries that allow at least ten seconds of life after firing activation, in addition to rapid-response capabilities. Dispensed in the initial format from standard 55 mm flare cartridge to equip at least three main platforms (Eurofighter Typhoon, Saab Gripen and Panavia Tornado).[78][79]

Eurojet is attempting to find funding to test a thrust vectoring nozzle (TVN) on a flight demonstrator.[80] Additionally, the RAF has sought to develop conformal fuel tanks (CFT) for their Typhoons to free up underwing space for weapons, and all Tranche 3 aircraft are fitted to accept these tanks.[81][82][N 4] On 22 April 2014, BAE systems announced a new round of wind tunnel tests to assess the aerodynamic characteristics of conformal fuel tanks (CFTs). The CFTs, which can be fitted to any Tranche 2/3 aircraft, can carry 1,500 litres each to increase the Typhoon's combat radius by a factor of 25% to 1,500 n miles (2,778 km).[83]

BAE Systems has completed development of its Striker II Helmet-Mounted Display that builds on the capabilities of the original Striker Helmet-Mounted Display, which is already in service on the Typhoon.[84] Striker II features a new display with more colour and can transition between day and night seamlessly eliminating the need for separate night vision googles. In addition, the helmet can monitor the pilot’s exact head position so it always knows exactly what information to display.[85] The system is compatible with ANR, a 3-D audio threats system and 3-D communications; these are available as customer options.[86]

In 2015, BAE Systems was awarded a £1.7 million contract to study the feasibility of a common weapon launcher that could be capable of carrying multiple weapons and weapon types on a single pylon.[87]

Also in 2015, Airbus flight tested a package of aerodynamic upgrades for the Eurofighter known as the Aerodynamic Modification Kit (AMK) that included fuselage strakes and leading-edge root extensions which increases wing lift by 25% resulting in an increased turn rate, tighter turning radius, and improved nose-pointing ability at low speed with angle of attack values around 45% greater than on the standard aircraft and roll rates up to 100% higher.[88] Eurofighter's Laurie Hilditch said these improvements should increase subsonic turn rate by 15% and give the Eurofighter the sort of "knife-fight in a phone box" turning capability enjoyed by rivals such as Boeing’s F/A-18E/F or the Lockheed Martin F-16, without sacrificing the transonic and supersonic high-energy agility inherent to its delta wing-canard configuration.[89]

In April 2016, Finmeccanica demonstrated the air-to-ground capabilities of its Mode 5 Reverse-Identification Friend-Foe (IFF) system integrated on an Italian Air Force Tranche 1 Eurofighter Typhoon. [90] This demonstration shows that it is possible to give pilots the ability to distinguish between friendly and enemy platforms in a simple, low-impact fashion using the aircraft’s existing transponder. [91] Finmeccanica says NATO is considering the system as a short- to mid-term solution for air-to-surface identification of friendly forces and thus avoid collateral damages due to friendly fire during close air support operations. [92]

Design

Airframe overview

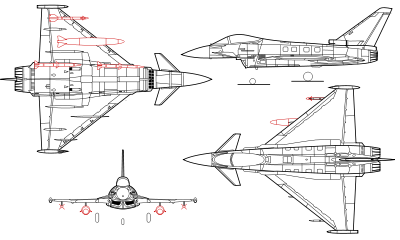

The Typhoon is a highly agile aircraft at both supersonic and low speeds, achieved through having an intentionally relaxed stability design. It has a quadruplex digital fly-by-wire control system providing artificial stability, as manual operation alone could not compensate for the inherent instability. The fly-by-wire system is described as "carefree", and prevents the pilot from exceeding the permitted manoeuvre envelope. Roll control is primarily achieved by use of the wing elevons. Pitch control is by operation of the foreplanes and elevons, the yaw control is by rudder.[93] Control surfaces are moved through two independent hydraulic systems, which also supply various other items, such as the canopy, brakes and undercarriage; powered by a 4,000 psi engine-driven gearbox.[94] Engines are fed by a chin double intake ramp situated below a splitter plate.

The Typhoon features lightweight construction (82% composites consisting of 70% carbon fibre composite materials and 12% glass fibre reinforced composites)[95] with an estimated lifespan of 6,000 flying hours.[96] The permitted lifespan, as opposed to the estimated lifespan, was 3,000 hours.

Radar signature reduction features

Although not designated a stealth fighter,[97][98] measures were taken to reduce the Typhoon's radar cross section (RCS), especially from the frontal aspect.[99][100] An example of these measures is that the Typhoon has jet inlets that conceal the front of the jet engine (a strong radar target) from radar. Many important potential radar targets, such as the wing, canard and fin leading edges, are highly swept, so will reflect radar energy well away from the front sector.[101] Some external weapons are mounted semi-recessed into the aircraft, partially shielding these missiles from incoming radar waves.[99] In addition radar-absorbent materials (RAM), developed primarily by EADS/DASA, coat many of the most significant reflectors, such as the wing leading edges, the intake edges and interior, the rudder surrounds, and strakes.[99][102]

The manufacturers have carried out tests on the early Eurofighter prototypes to optimise the low observability characteristics of the aircraft from the early 1990s. Testing at BAE's Warton facility on the DA4 prototype measured the RCS of the aircraft and investigated the effects of a variety of RAM coatings and composites.[103] Another measure to reduce the likelihood of discovery is the use of passive sensors, which minimises the radiation of treacherous electronic emissions. While canards generally have poor stealth characteristics,[104] the flight control system is designed to maintain the elevon trim and canards at an angle at which they have the smallest RCS.[105][106]

Cockpit

The Typhoon features a glass cockpit without any conventional instruments. It incorporates three full colour multi-function head-down displays (MHDDs) (the formats on which are manipulated by means of softkeys, XY cursor, and voice (Direct Voice Input or DVI) command), a wide angle head-up display (HUD) with forward-looking infrared (FLIR), a voice and hands-on throttle and stick (Voice+HOTAS), a Helmet Mounted Symbology System (HMSS), a Multifunctional Information Distribution System (MIDS), a manual data-entry facility (MDEF) located on the left glareshield and a fully integrated aircraft warning system with a dedicated warnings panel (DWP). Reversionary flying instruments, lit by LEDs, are located under a hinged right glareshield.[107] Access to the cockpit is normally via either a telescopic integral ladder or an external version. The integral ladder is stowed in the port side of the fuselage, below the cockpit.[108]

User needs were given a high priority in the cockpit's design; both layout and functionality was created through feedback and assessments from military pilots and a specialist testing facility.[109] The aircraft is controlled by means of a centre stick (or control stick) and left hand throttles, designed on a Hand on Throttle and Stick (HOTAS) principle to lower pilot workloads.[110] Emergency escape is provided by a Martin-Baker Mk.16A ejection seat, with the canopy being jettisoned by two rocket motors.[111] The HMSS was delayed by years but should have been operational by late 2011.[112] Standard g-force protection is provided by the full-cover anti-g trousers (FCAGTs).[113] a specially developed g suit providing sustained protection up to 9 g. German Air Force and Austrian Air Force pilots wear a hydrostatic g-suit called Libelle (dragonfly) Multi G Plus instead,[114][115][116] which also provides protection to the arms, theoretically giving more complete g tolerance.

In the event of pilot disorientation, the Flight Control System allows for rapid and automatic recovery by the simple press of a button. On selection of this cockpit control the FCS takes full control of the engines and flying controls, and automatically stabilises the aircraft in a wings level, gentle climbing attitude at 300 knots, until the pilot is ready to retake control.[117] The aircraft also has an Automatic Low-Speed Recovery system (ALSR) which prevents it from departing from controlled flight at very low speeds and high angle of attack. The FCS system is able to detect a developing low-speed situation and to raise an audible and visual low-speed cockpit warning. This gives the pilot sufficient time to react and to recover the aircraft manually. If the pilot does not react, however, or if the warning is ignored, the ALSR takes control of the aircraft, selects maximum dry power for the engines and returns the aircraft to a safe flight condition. Depending on the attitude, the FCS employs an ALSR "push", "pull" or "knife-over" manoeuvre.[118]

The Typhoon Direct Voice Input (DVI) system uses a speech recognition module (SRM), developed by Smiths Aerospace (now GE Aviation Systems) and Computing Devices (now General Dynamics UK). It was the first production DVI system used in a military cockpit. DVI provides the pilot with an additional natural mode of command and control over approximately 26 non-critical cockpit functions, to reduce pilot workload, improve aircraft safety, and expand mission capabilities. An important step in the development of the DVI occurred in 1987 when Texas Instruments completed the TMS-320-C30, a digital signal-processor, enabling reductions in the size and system complexity required. The project was given the go-ahead in July 1997, with development and pilot assessment carried out on the Eurofighter Active Cockpit Simulator at BAE Systems Warton.[119]

The DVI system is speaker-dependent, requiring each pilot to create a template. It is not used for safety-critical or weapon-critical tasks, such as weapon release or lowering of the undercarriage, but is used for a wide range of cockpit functions.[120][121] Voice commands are confirmed by visual or aural feedback, and serves to reduce pilot workload. All functions are also achievable by means of a conventional button-press or soft-key selections; functions include display management, communications, and management of various systems.[122] EADS Defence and Security in Spain has worked on a new non-template DVI module to allow for continuous speech recognition, speaker voice recognition with common databases (e.g. British English, American English, etc.) and other improvements.[122]

Avionics

Navigation is via both GPS and an inertial navigation system. The Typhoon can use Instrument Landing System (ILS) for landing in poor weather. The aircraft also features an enhanced ground proximity warning system (GPWS) based on the TERPROM Terrain Referenced Navigation (TRN) system used by the Panavia Tornado.[123] The Multifunctional Information Distribution System (MIDS) provides a Link 16 data link.[124]

The aircraft employs a sophisticated and highly integrated Defensive Aids Sub-System named Praetorian[125] (formerly called EuroDASS).[126] Praetorian monitors and responds automatically to air and surface threats, provides an all-round prioritised assessment, and can respond to multiple threats simultaneously. Threat detection methods include a Radar warning receiver (RWR), a Missile Warning System (MWS) and a laser warning receiver (LWR, only on UK Typhoons). Protective countermeasures consist of chaff, flares, an electronic countermeasures (ECM) suite and a towed radar decoy (TRD).[127] The ESM-ECM and MWS consists of 16 AESA antenna array assemblies and 10 radomes.[128][129]

Traditionally each sensor in an aircraft is treated as a discrete source of information; however this can result in conflicting data and limits the scope for the automation of systems, hence increasing pilot workload. To overcome this, the Typhoon employs what are now known as sensor fusion techniques (in a similar fashion to the U.S. F-22 Raptor). In the Typhoon fusion of all data sources is achieved through the Attack and Identification System, or AIS. The AIS combines data from the major on-board sensors along with any information obtained from off-board platforms such as AWACS, ASTOR, and Eurofighter own Multi-function Information Distribution System (MIDS). Additionally the AIS integrates all the other major offensive and defensive systems such as the DASS, Navigation, ACS and Communications. The AIS physically comprises two essentially separate units: the Avionic Computer (AC) and the Navigation Computer (NC), linked via the STANAG-3910 databus to the other major systems such as the ACS, ECR-90/CAPTOR, PIRATE, etc. Both the AC and NC are identical in design, being a modular unit based on Motorola 68020 CPU's with 68882 Maths co-processors, as well as several custom RISC-based processors utilised to accelerate floating point and matrix operations.

By having a single source of information, pilot workload should be reduced by removing the possibility of conflicting data and the need for cross-checking, improving situational awareness and increasing systems automation. In practice the AIS should allow the Eurofighter to identify targets at distances in excess of 150 nm and acquire and auto-prioritise them at over 100 nm. In addition the AIS offers the ability to automatically control emissions from the aircraft, so called EMCON (from EMissions CONtrol). This should aid in limiting the detectability of the Typhoon by opposing aircraft further reducing pilot workload.[130]

Radar and Sensors

CAPTOR radar

The Eurofighter operates automatic Emission Controls (EMCON) to reduce the Electro-Magnetic emissions of the current CAPTOR mechanically scanned Radar.[99] The Captor-M has three working channels, one intended for classification of jammer and for jamming suppression.[131] A succession of radar software upgrades have enhanced the air-to-air capability of the Captor-M radar.[64] These upgrades have included the R2P programme (initially UK only, and known as T2P when 'ported' to the Tranche 2 aircraft)[132] which is being followed by R2Q/T2Q. R2P was applied to eight German Typhoons deployed on Red Flag Alaska in 2012.

The CAPTOR-E is an Active electronically scanned array derivative of the original CAPTOR radar, also known as CAESAR (from CAPTOR Active Electronically Scanned Array Radar) being developed by the EuroRADAR Consortium, led by Selex ES. The German BW-Plan 2009 indicated that Germany intended to equip/retrofit their Eurofighters with the AESA Captor-E from 2012,[133] but the contract award has been delayed until at least mid 2014.[81]

Synthetic Aperture Radar is expected to be fielded as part of the AESA radar upgrade which will give the Eurofighter an all-weather ground attack capability.[134] The conversion to AESA will also give the Eurofighter a low probability of intercept radar with much better jam resistance.[135][136] These include an innovative design with a gimbal to meet RAF requirements for a wider scan field than a fixed AESA.[137] The coverage of a fixed AESA is limited to 120° in azimuth and elevation.[138] A senior EADS radar expert has claimed that Captor-E is capable of detecting an F-35 from roughly 59 km away.[139]

In May 2007, Eurofighter Development Aircraft 5 made the first flight with the CAPTOR-E demonstrator system,[140][141] Tranche 2 aircraft use the non-AESA mechanically scanned Captor-M which incorporates weight and space provisions for possible upgrade to CAESAR (AESA) standard in the future.[142][143] In June 2013, Chris Bushell of Selex ES warned that the failure of European nations to invest in an AESA radar was putting export orders at risk.[144] In November BAE responded that work on an AESA radar continued, to protect exports.[145] On 22 June 2011, it was announced that the partner nations had agreed to fund development of the Captor-E radar, with entry into service planned for 2015.[146] The British are pursuing an independent Technology Demonstrator Programme called Bright Adder, which will give the Typhoon an Electronic Attack mode among other things.[147] Bright Adder is based on Qinetiq's ARTS radar demonstrator for the Tornado GR4 and could evolve into an alternative to the main E-Scan project should E-Scan falter.[147]

The first flight of a Eurofighter equipped with a "mass model" of the Captor-E occurred in late February 2014, with flight tests of the actual radar expected later that year. Tranche 3 Typhoons have the mechanical, electrical and cooling enhancements needed to operate the radar.[148] At the 2014 Farnborough Airshow the UK MOD announced that it had awarded BAE Systems a £72 million ($124 million) contract to conduct national-specific testing on a prototype AESA system. On 19 November 2014 the contract to upgrade to the Captor-E was signed at the office's of EuroRadar lead Selex ES in Edinburgh, in a deal worth €1bn.[149] Availability of the radar, for Tranche 2 and 3A aircraft, was anticipated by 2016-17,[150] but there are no orders for the radar system from the partner nations.[151][152] However, Kuwait became the launch customer for the Captor-E active electronically scanned array radar in April 2016.[153]

IRST

The Passive Infra-Red Airborne Track Equipment (PIRATE) system is an infrared search and track (IRST) system mounted on the port side of the fuselage, forward of the windscreen. Selex ES is the lead contractor which, along with Thales Optronics (system technical authority) and Tecnobit of Spain, make up the EUROFIRST consortium responsible for the system's design and development. Eurofighters starting with Tranche 1 block 5 have the PIRATE. The first Eurofighter Typhoon with PIRATE-IRST was delivered to the Italian Aeronautica Militare in August 2007.[154] More advanced targeting capabilities can be provided with the addition of a targeting pod such as the LITENING pod.[155]

PIRATE operates in two IR bands, 3–5 and 8–11 micrometres. When used with the radar in an air-to-air role, it functions as an infrared search and track system, providing passive target detection and tracking. In an air-to-surface role, it performs target identification and acquisition. By supercooling the sensor even small variations in temperature can be detected at long range. Although no definitive ranges have been released an upper limit of 80 nm has been hinted at, a more typical figure would be 30 to 50 nm.[156] It also provides a navigation and landing aid. PIRATE is linked to the pilot’s helmet-mounted display.[157] It allows the detection of both the hot exhaust plumes of jet engines as well as surface heating caused by friction; processing techniques further enhances the output, giving a near-high resolution image of targets. The output can be directed to any of the Multi-function Head Down Displays, and can also be overlaid on both the Helmet Mounted Sight and Head Up Display.

The IIR sensor has a stabilised mount so that it can maintain a target within its field of view. Up to 200 targets can be simultaneously tracked using one of several different modes; Multiple Target Track (MTT), Single Target Track (STT), Single Target Track Ident (STTI), Sector Acquisition and Slaved Acquisition. In MTT mode the system will scan a designated volume space looking for potential targets. In STT mode PIRATE will provide high precision tracking of a single designated target. An addition to this mode, STT Ident allows for visual identification of the target, the resolution being superior to CAPTOR's. Both Sector and Slave Acquisition demonstrate the level of sensor fusion present in the Typhoon. When in Sector Acquisition mode PIRATE will scan a volume of space under direction of another onboard sensor such as CAPTOR. In Slave Acquisition, off-board sensors are used with PIRATE being commanded by data obtained from an AWACS for example. When a target is found in either of these modes, PIRATE will automatically designate it and switch to STT.

Once a target has been tracked and identified PIRATE can be used to cue an appropriately equipped short range missile, i.e. a missile with a high off-boresight tracking capability such as ASRAAM. Additionally the data can be used to augment that of CAPTOR or off-board sensor information via the AIS. This should enable the Typhoon to overcome severe ECM environments and still engage its targets.[130] Additionally PIRATE has a passive ranging capability[158] although the system remains limited when it comes to provide passive firing solutions, as the PIRATE lacks laser rangefinder.

Engines

The Eurofighter Typhoon is fitted with two Eurojet EJ200 engines, each capable of providing up to 60 kN (13,500 lbf) of dry thrust and >90 kN (20,230 lbf) with afterburners. The EJ200 engine combines the leading technologies from each of the four European companies, utilising Advanced digital control and health monitoring; wide chord aerofoils and single crystal turbine blades; and a convergent / divergent exhaust nozzle to give excellent thrust-to-weight ratio, multimission capability, supercruise performance, low fuel consumption, low cost of ownership, modular construction and significant growth potential.[159][160][161]

The Typhoon is capable of supersonic cruise without using afterburners (referred to as supercruise). Air Forces Monthly gives a maximum supercruise speed of Mach 1.1 for the RAF FGR4 multirole version,[162] however in a Singaporean evaluation, a Typhoon managed to supercruise at Mach 1.21 on a hot day with a combat load.[163] The Eurofighter Company states that the Typhoon can supercruise at Mach 1.5.[164] As with the F-22, the Eurofighter can launch weapons while under supercruise to extend their ranges via this "running start".[165]

In 2007, the EJ200 engine has accumulated 50,000 Engine Flying Hours in service with the four Nation Air Forces (Germany, UK, Spain and Italy).[166]

In addition to the potential for increased in thrust of up to 30%, the EJ200 engine has the potential to be fitted with Thrust Vectoring Nozzles (TVN), that the Eurofighter and Eurojet consortium have been actively developing and testing, primarily for export, but also for future upgrades of the fleet. TVN could reduce fuel burn on a typical Typhoon mission by up to 5%, as well as increase available thrust in supercruise by up to 7% and take-off thrust by 2%.[167]

Performance

The Typhoon's combat performance, compared to the F-22 Raptor and the upcoming F-35 Lightning II fighters and the French Dassault Rafale, has been the subject of much discussion.[168] In March 2005, United States Air Force Chief of Staff General John P. Jumper, then the only person to have flown both the Eurofighter Typhoon and the Raptor, talked to Air Force Print News about these two aircraft. He said,

The Eurofighter is both agile and sophisticated, but is still difficult to compare to the F/A-22 Raptor. They are different kinds of airplanes to start with; it's like asking us to compare a NASCAR car with a Formula One car. They are both exciting in different ways, but they are designed for different levels of performance. …The Eurofighter is certainly, as far as smoothness of controls and the ability to pull (and sustain high G forces), very impressive. That is what it was designed to do, especially the version I flew, with the avionics, the color moving map displays, etc. – all absolutely top notch. The maneuverability of the airplane in close-in combat was also very impressive.[169][170]

In the 2005 Singapore evaluation, the Typhoon won all three combat tests, including one in which a single Typhoon defeated three RSAF F-16s, and reliably completed all planned flight tests.[171] In July 2009, Former Chief of Air Staff for the Royal Air Force, Air Chief Marshal Sir Glenn Torpy, said that "The Eurofighter Typhoon is an excellent aircraft. It will be the backbone of the Royal Air Force along with the JSF".[172]

In July 2007, Indian Air Force Su-30MKI fighters participated in the Indra-Dhanush exercise with Royal Air Force's Typhoon. This was the first time that the two jets had taken part in such an exercise.[173][174] The IAF did not allow their pilots to use the MKI's radar during the exercise to protect the highly classified N011M Bars.[175] RAF Tornado pilots stated the Su-30MKI had superior manoeuvrability, but the IAF pilots were also impressed by the Typhoon's agility.[176]

Armament

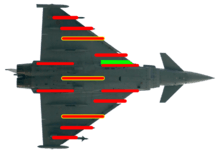

.jpg)

The Typhoon is a multi-role fighter with maturing air-to-ground capabilities. The initial absence of air-to-ground capability is believed to have been a factor in the type's rejection from Singapore's fighter competition in 2005. At the time it was claimed that Singapore was concerned about the delivery timescale and the ability of the Eurofighter partner nations to fund the required capability packages.[177] Tranche 1 aircraft could drop laser-guided bombs in conjunction with third-party designators but the anticipated deployment of Typhoon to Afghanistan meant that the UK required self-contained bombing capabilities before the other partners.[N 5] On 20 July 2006, a £73m deal was signed for Change Proposal 193 (CP193) to give an "austere" air-to-surface capability using GBU-16 Paveway II[179] and Rafael/Ultra Electronics Litening III laser designator[180] for the RAF Tranche 1 Block 5 aircraft.[181] Aircraft with this upgrade were designated Typhoon FGR4 by the RAF.

Similar capability was added to Tranche 2 aircraft on the main development pathway as part of the Phase 1 Enhancements. P1Ea (SRP10) entered service in 2013 Q1 and added the use of Paveway IV, EGBU16 and the cannon against surface targets.[64] P1Eb (SRP12) added full integration with GPS bombs such as GBU-10 Paveway II, GBU-16 Paveway II, Paveway IV and a new real-time operating system that allows multiple targets to be attacked in a single run.[64] This new system will form the basis for future weapons integration by individual countries under the Phase 2 Enhancements. A definite schedule has not yet been agreed, but will likely see the Storm Shadow and KEPD 350 (Taurus) cruise missiles integrated in 2015, followed by Brimstone anti-tank missiles.[64]

An anti-shipping capability is required by 2017, and such a capability is also important for potential export customers such as India;[182] Eurofighter is studying integrating the Boeing Harpoon or MBDA Marte or Sea Brimstone missiles onto the Typhoon for a maritime attack capability.[183] The Typhoon can accommodate two RBS-15 or three Marte-ERP under each wing but neither has been integrated yet.[182]

In addition to the missile armament options, the Typhoon also carries a specially developed variant of the Mauser BK-27 27mm cannon armament that was developed originally for the Panavia Tornado. This is a single-barrel, electrically fired, gas-operated revolver cannon with a new linkless feed system, capable of firing up to 1700 rounds per minute. There was a proposal on cost grounds in 1999 to limit this gun-armament fit to the first 53 batch-1 aircraft destined for the RAF, only on the basis that the guns would be used as ballast and not used operationally,[184] but this decision was reversed in 2006.[185]

Operational history

Germany and Spain

On 4 August 2003, Germany accepted the first series production Eurofighter (GT003).[186] Also that year, Spain took delivery of its first series production aircraft.[187]

Italy

On 16 December 2005, the Typhoon reached initial operational capability (IOC) with the Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare). Its Typhoons were put into service as air defence fighters at the Grosseto Air Base, and immediately assigned to Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) at the same base.[188]

On 17 July 2009, Italian Air Force Typhoons were deployed to protect Albania's airspace.[189]

On 29 March 2011, Italian Air Force Eurofighter Typhoons began flying combat air patrol missions in support of NATO's Operation Unified Protector in Libya.[190]

United Kingdom

On 9 August 2007, the UK's Ministry of Defence reported that No. 11 Squadron RAF of the RAF, which stood up as a Typhoon squadron on 29 March 2007, had taken delivery of its first two multi-role Typhoons.[191] Two of 11 Squadron's Typhoons were sent to intercept a Russian Tupolev Tu-95 approaching British airspace on 17 August 2007.[192] The RAF Typhoons were declared combat ready in the air-to-ground role by 1 July 2008.[193] The RAF Typhoons were projected to be ready to deploy for operations by mid-2008.[191]

In September 2009, four RAF Typhoons were deployed to RAF Mount Pleasant replacing the Tornado F3s defending the Falkland Islands. The government of Argentina "is understood to have made a formal protest".

On 18 March 2011, British Prime Minister David Cameron announced that the UK would deploy Typhoons, alongside Panavia Tornados, to enforce a no-fly zone in Libya.[194] On 20 March 10 Typhoons from RAF Coningsby and RAF Leuchars arrived at the Gioia del Colle airbase in southern Italy.[195] On 21 March RAF Typhoons flew their first ever combat mission while patrolling the no-fly zone.[196] On 29 March, it was revealed that the RAF were short of pilots to fly the required number of sorties over Libya and were having to divert personnel from Typhoon training to meet the shortfall.[197]

On 12 April 2011, a mixed pair of RAF Typhoon and Tornado GR4[198] dropped precision-guided bombs on ground vehicles operated by Gaddafi forces that were parked in an abandoned tank park.[199] Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton, revealed during the Royal Aeronautical Society's Aerospace 2011 conference in London, that each aircraft dropped one GBU-16 Paveway II 454 kg (1,000 lb) laser-guided bomb which struck "very successfully and very accurately". The event represented "a significant milestone in the delivery of multi-role Typhoon."[200] Target designation was provided by the Tornados with their Litening III targeting pods due to the lack of Typhoon pilots trained in air-to-ground missions.[201]

The National Audit Office observed in 2011 that the distribution of the Eurofighter's parts supply and repairs over several countries has led to parts shortages, long timescales for repairs and the cannibalisation of some aircraft to keep others flying.[202]The UK's then Defence Secretary Liam Fox admitted on 14 April 2011 that Britain's Eurofighter Typhoon jets were grounded in 2010 due to shortage of spare parts. The RAF has been "cannibalising" aircraft for spare parts in a bid to keep the maximum number of Typhoons operational on any given day. The Ministry of Defence had warned the problems were likely to continue until 2015.[203]

In July 2012, UK Defence Secretary Philip Hammond suggested that a follow-on buy of F-35A aircraft would be determined by the Strategic Defence and Security Review in 2015, with the aim of replacing UK's Typhoons around 2030.[204] The UK is to decide what mix of manned and unmanned aircraft to replace its Eurofighters with sometime between 2015 and 2020.[205]

It was announced in December 2013 that No. 2 Squadron will be the fifth Typhoon Squadron and will convert from the Panavia Tornado and reform at RAF Lossiemouth from 1 April 2015.[206]

By July 2014, a dozen RAF Tranche 2 Typhoons had been upgraded with Phase 1 Enhancement (P1E) capability to enable them to use the Paveway IV guided bomb; the Tranche 1 version had used the GBU-12 Paveway II in combat over Libya, but the Paveway IV can be set to explode above or beneath a target and to hit at a set angle. The British are aiming to upgrade their Typhoons to be able to carry the Storm Shadow cruise missile and Brimstone air-to-ground missile by 2018 to ensure they have manned aircraft configured with strike capabilities with trained crews by the time the Tornado GR4 is retired the following year; the Defence Ministry is also funding research for a common launcher system that could also drop the Selective Precision Effects at Range (Spear) III networked precision-guided weapon from the Typhoon, which is already planned for the F-35. RAF Tranche 1 Typhoons are too structurally and technically different from later models, so the British have decided that beginning in 2015 or 2016, the older models will be switched out for Tranche 2 and 3 versions, a process which will remove the Tranche 1 aircraft from service around 2020 to be stripped for parts to support newer versions to lower costs.[207]

On 1 July 2015 it was reported that Typhoons from No. 2 Squadron were training with Type 45 destroyers in an Air-Maritime Integration (AMI) role, admitting that the service had recently neglected the role following the decommission of the RAF Nimrod Maritime Patrol Aircraft.[208][209]

In the 2015 Strategic Defense and Security Review (SDSR), it was decided to retain some of the Tranche 1 aircraft to increase the number of front-line squadrons from five to seven and to boost the out-of-service date from 2030 to 2040 as well as implementing the Captor-E AESA radar in later tranches.[210][211][212] It was announced that Typhoons would be deployed to Malta as security for the 2015 CHOGM.[213]

Due to the limited ground attack capabilities of the RAF Typhoons in the campaign against ISIL, the UK has delayed the retirement of one squadron of Tornados and is attempting to bring forward the deployment of Brimstone missiles on the Eurofighters to 2017.[214]

On 3 December 2015 six Typhoon FGR4s deployed to RAF Akrotiri to support operations against ISIL. The following evening the Typhoons, accompanied by Tornados, attacked targets in Syria.[215]

In mid-October 2016, four Typhoons from RAF II (AC) Squadron visited Japan with Voyager and C-17 aircraft to participate, alongside F-2 and F-15 fighter aircraft, in a joint exercise with the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.[216][217]

Austria

On 2 July 2002, the Austrian government announced the decision to buy the Typhoon as its new air defence aircraft, the Typhoon having beaten the General Dynamics F-16 and the Saab JAS 39 Gripen in competition.[218] The purchase of 18 Typhoons was agreed on 1 July 2003, and included training, logistics, maintenance, and a simulator. On 26 June 2007, Austrian Minister for Defense Norbert Darabos announced a reduction to 15 aircraft.[219] The first aircraft was delivered on 12 July 2007 and formally entered service in the Austrian Air Force.[220] A 2008 report by the Austrian Government oversight office, the Rechnungshof, calculated that instead of getting 18 Tranche 2 jets at a price of €109 million each, as stipulated by the original contract, the revised deal agreed by Minister Darabos meant that Austria was paying an increased unit price of €114 million for 15 partially used, Tranche 1 jets.[221] Austrian prosecutors are investigating allegations that up to 100 million Euros were made available to lobbyists to influence the purchase decision in favour of the Eurofighter.[222] By October 2013, all eurofighters in service with Austria had been upgraded to the latest Tranche 1 standard. [223] In 2014, due to defense budget restrictions, there were only 12 pilots to fly the 15 Eurofighters in Austria's service.[224][225]

Saudi Arabia

On 18 August 2006 it was announced that Saudi Arabia had agreed to purchase 72 Typhoons.[226] In December 2006 it was reported in The Guardian that Saudi Arabia had threatened to buy French Rafales because of a UK Serious Fraud Office investigation into the Al Yamamah ("the dove") defence deals which commenced in the 1980s.[227]

On 14 December 2006, Britain's attorney general, Lord Goldsmith, ordered that the Serious Fraud Office discontinue its investigation in the BAE Systems' alleged bribery to senior Saudi officials in the al-Yamamah contracts, citing "the need to safeguard national and international security".[228] The Times has raised the possibility that RAF production aircraft will be diverted as early Saudi Arabian aircraft, with the service forced to wait for its full complement of aircraft.[229] This arrangement would mirror the diversion of RAF Tornados to the RSAF. The Times has also reported that such an arrangement will make the UK purchase of its Tranche 3 commitments more likely.[229] On 17 September 2007, Saudi Arabia confirmed it had signed a GB£4.43 billion contract for 72 aircraft.[230] 24 aircraft will be at the Tranche 2 build standard, previously destined for the UK RAF, the first being delivered in 2008. The remaining 48 aircraft were to be assembled in Saudi Arabia and delivered from 2011,[157] but following contract renegotiations in 2011 it was agreed that all 72 aircraft would be assembled by BAE Systems in the UK with the last 24 aircraft being built to Tranche 3 capability.[231] Saudi Arabia is considering an order of 24 additional jets in the future.[232] More recent reports suggest that number may be as high as 60[233] or 72,[234] but this may have been superseded by Saudi Arabia's decision in August 2010 to purchase 84 new F-15SAs.[235]

On 29 September 2008 the United States Department of State approved the sale, required because of a certain technology governed by the ITAR process which was incorporated into the MIDS of the Eurofighter.[236][237][238][239]

On 22 October 2008, the first Typhoon in the colours of the Royal Saudi Air Force flew for the first time at BAE Systems' Warton Aerodrome, marking the start of the test flight programme for RSAF aircraft.[240] Following the official handover of the first Eurofighter Typhoon to the Royal Saudi Air Force on 11 June 2009, the delivery ferry flight took place on 23 June 2009. Since 2010, BAE Systems has been training Saudi Arabian personnel at their factory in Warton, in preparation for setting up an assembly plant in Saudi Arabia.[241]

By 2011, 24 Tranche 2 Eurofighter Typhoons had been delivered to Saudi Arabia, consisting of 18 single-seat and 6 two-seat aircraft. After that, BAE and Riyadh entered into discussions over configurations and price of the rest of the 72-plane order. Deliveries resumed in early 2013, with the discussions still going on, with four trainers and two more single-seat Typhoons. Another two single-seat models were delivered in October 2013. By 25 October 2013, Saudi Arabia had received 32 Eurofighter Typhoons. Two more aircraft are to be delivered to Saudi Arabia by the end of 2013.[242]

On 19 February 2014, BAE announced that the Saudis had agreed to a price increase over the existing contract.[243]

Saudi Arabia's UK-supplied Eurofighter Typhoons are playing a central role in Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen.[244]

In February 2015, Saudi Typhoons attacked ISIS targets over Syria using Paveway IV bombs for the first time.[245]

In October 2016, it was reported that BAE Systems was in talks with Saudi Arabia about an order for another 48 aircraft.[246]

Oman

During the 2008 Farnborough Airshow it was announced that Oman was in an "advanced stage" of discussions towards purchasing Typhoons as a replacement for its SEPECAT Jaguar aircraft.[247][248] Through 2010 Oman remained interested in ordering Typhoons.[249] though the Saab JAS 39 Gripen was also being considered.[250] In the interim Oman ordered 12 additional F-16s in December 2011.[251] On 21 December 2012, the Royal Air Force of Oman became the Typhoon's seventh customer when BAE Systems and Oman announced an order for 12 Typhoons to enter service in 2017.[252]

Kuwait

In June 2015, it was reported that Kuwait was in talks with the Italian Air Force and Alenia Aermacchi about the potential purchase of up to 28 Eurofighter Typhoons for two squadrons. On 11 September 2015, Eurofighter confirmed that an agreement had been reached to supply Kuwait with 28 aircraft.[253][254] On 1 March 2016, the Kuwaiti National Assembly approved the procurement of 22 single-seat and six twin-seat Typhoons, which will be assembled at Caselle, Italy.[255] On 5 April 2016, Kuwait signed a contract with Finmeccanica valued at €7.957 billion (US $9.062 billion) for the supply of the 28 aircraft, all to third tranche standard. The Kuwaiti aircraft will be the first Typhoons to receive the Captor-E active electronically scanned array radar, with two instrumented production aircraft from the UK and Germany currently undergoing ground-based integration trials. The Typhoons will be fitted with Leonardo-Finmeccanica's Praetorian defensive aids suite and PIRATE infrared search and track system. The contract involves the production of aircraft in Italy and covers logistics, operational support and the training of flight crews and ground personnel. It also encompasses infrastructure work at the Ahmed Al Jaber Air Base, where the Typhoons will be based. Aircraft deliveries will begin in 2019.[256][257][258][259]

Potential exports

The partner companies have divided the world into regions with BAE selling Typhoons to the Middle East, Alenia Aermacchi pitching to Turkey, and EADS offering to Latin America, India and South Korea.[260][261][262][263] Senior vice-president of Eurofighter sales Peter Maute has said that the Eurofighter could provide a complementary capability to stealth fighters.[264]

Bahrain

On 8 August 2013, BAE officials commented that the Royal Bahraini Air Force was considering buying the Eurofighter Typhoon. The Eurofighter Typhoon is being considered along with the JAS 39 Gripen, Dassault Rafale, and F-35 Lightning II for Bahrain's future fighter needs.[265]

Belgium

In July 2014, the Eurofighter Typhoon was noted to be one of the contenders to replace Belgium's fleet of ageing F-16A/B MLU's by 2023 as part of the "air combat capability successor program". The requirement stands for 40 aircraft. Other contenders include the SAAB Gripen-E/F, Dassault Rafale, F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and the F-35A Lightning II. A decision is expected by 2016 and contracts signed by 2018.[266]

The opposition in the federal parliament of Belgium claimed that a decision was already made in favour of the American F-35 and that the competition was a cover-up. The opposition concluded that the requirements for the new aircraft were set up such a way that "only the F-35 could possibly meet the requirements". Further more a supposedly leaked document from the Belgian military stated that for Belgium to remain in a strong position in NATO, the aircraft should have a launch capability for the B61 nuclear bombs supposedly stored at the Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium. Coalition parties have been denying such allegations. They say a decision will be made in 2018 and that parliament could still vote against the selected aircraft.[267]

Bulgaria

In January 2015, it was revealed that the Eurofighter Typhoon is one of the contenders for Bulgaria's MiG-29 replacement program. This would consist of 8 second hand Eurofighters from ex-Italian service and is in competition with offers for 16 surplus F-16s from the United States, an unknown number of surplus F-16s from Belgium or 16 surplus Saab Gripen C/Ds from Sweden.[268][269]

Canada

In December 2012, the Canadian government decided that F-35 costs were much higher than earlier anticipated and hence are looking at the Eurofighter as well as four other fighters to replace their ageing CF-18s.[270] As of January 2014 it seems unlikely that a decision on a replacement would be taken before the next federal election in October 2015.[271] This election has occurred and Canada is leaning more towards US fighters like the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet or back to the F-35.[272]

Finland

In October 2014 the Finnish broadcaster Yle announced that the Finnish Air Force was considering the replacement of its F/A-18 Hornets (which entered service in 1995), thus raising the issue of whether the Eurofighter could be a potential successor.[273] In June 2015, a working group set up by the Finnish MoD proposed starting the so-called HX program to replace Finnish Air Force's current fleet of ageing F/A-18 Hornet, which will reach the end of their service life by the end of the 2020s. The group recognises five potential types: Boeing Super Hornet, Dassault Rafale, Eurofighter Typhoon, Lockheed Martin JSF F-35 and Saab JAS Gripen.[274]

Indonesia

Eurofighter and other fighter builders responded to a request for information issued by the Indonesian government in January 2015 for a fighter to replace the F-5s currently in service with the Air Force.[275] Eurofighter is offering its latest version of the Typhoon, equipped with Captor-E AESA radar, for Indonesia’s F-5 replacement programme.[276]

Malaysia

In December 2009, BAE Systems announced plans to market the Typhoon to the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) to replace its Mikoyan MiG-29Ns. According to the Regional Director-Business Development Dave Potter, the Typhoon's multi-role capabilities allow it to replace the MiG-29N.[277] Other contenders include Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, Dassault Rafale and JAS 39 Gripen NG.[278] In October 2016, Malaysia's Minister of Defence stated that the Dassault Rafale and Eurofighter Typhoon were the only competitors to replace its Mig-29s.[279]

Peru

On 4 February 2013 Spain announced a proposed sale of 18 Tranche 1 aircraft to the Peruvian Air Force, at a reported value of €45 million each. The intention was to transfer aircraft currently in Spanish service within a year of contract signature. Talks had been ongoing since November 2012 but the Eurofighter Typhoon is still in contention with the Saab Gripen NG and Sukhoi Su-30/35.[280]

Poland

Poland is planning to purchase 64 multirole combat aircraft from 2021 in an update to the country's modernisation plans, it has been revealed. The new fighters will replace the Polish Air Force's fleet of Sukhoi Su-22M4 'Fitter-K' ground attack aircraft and Mikoyan MiG-29 'Fulcrum-A' fighter aircraft. Planned open tender procedure could include the F-35 Lightning II, JAS 39 Gripen E/F, the newest variants of Eurofighter Typhoon and Dassault Rafale, and the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.[281][282][283][284]

Serbia

In 2010, the government of Serbia displayed open interest in the Eurofighter and competing products.[285] In June 2013, defence minister Aleksandar Vučić suggested that Serbia might purchase six MiG-29M/M2 instead.[286]

Vietnam

In June 2015 it was reported that Vietnam had been in discussions about the purchase of Eurofighter Typhoons to replace MiG-21s in their aircraft inventory. The talks were reported as ongoing but no decision was expected soon. Saab's Gripen E and Sukhoi's T-50 were also involved in the discussions for Vietnam's next fighter requirement.[287]

Failed bids

Denmark

The Royal Danish Air Force is replacing its ageing fleet of F-16AM and F-16BMs. Besides Eurofighter Typhoon there were two other competitors—the Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornet and the F-35 Lightning II. Denmark is a level-3 partner in the Joint Strike Fighter programme, and has already invested US$200 million.

On 12 May 2016 the Danish minority government recommended that 27 F-35A fighters, instead of 34 Typhoons, should be procured.[288][289] On 9 June the Danish parliament selected the Joint Strike Fighter.[290]

Greece

In 1999, the Greek government agreed to acquire 20 Typhoons to replace its existing second-generation combat aircraft.[291] The purchase was put on hold due to budget constraints, largely driven by other development programmes and the need to cover the cost of the 2004 Summer Olympics. In June 2006 the government announced a €22 billion multi-year acquisition plan intended to provide the necessary budgetary framework to enable the purchase of a next-generation fighter over the next 10 years and the Typhoon was under consideration to fill this requirement.[292] In December 2011 it was announced that the Eurofighter consortium office in Greece was to close because Greece would not be in a position to order any new aircraft before 2018 or 2020.[293]

India

Eurofighter was one of the six aircraft competing for the Indian MRCA competition for 126 multi-role fighters. In April 2011, the Indian Air Force (IAF) shortlisted the Dassault Rafale and Eurofighter Typhoon for the US$10.4 billion contract.[294] On 31 January 2012, the IAF announced the Rafale as the preferred bidder in the competition.[295][296]

Japan

In March 2007, Jane's Information Group reported that the Typhoon was the favourite to win the contest for Japan's next-generation fighter requirement.[297] The other competitors then were the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle.[297] On 17 October 2007, Japanese Defence Minister Shigeru Ishiba confirmed that Japan may buy the Typhoon. Although the F-22 Raptor was in his words "exceptional", it was not "absolutely necessary for Japan", and the Typhoon was the best alternative.[298] The F-22 is currently unavailable for export per US law. During a visit to Japan in June 2009, Andy Latham of BAE pointed out that while F-22 exports were restricted to keep advanced military technology from falling into the wrong hands, selling the Typhoon would take a "no black box approach", that is that even licensed production and integration with Japanese equipment would not carry the risk of leakage of restricted military technology.[299] In July 2010, it was reported that the Japan Air Self-Defense Force favoured acquiring the F-35 ahead of the Typhoon and the F/A-18E/F to fulfill its F-X requirement due to its stealth characteristics, but the Defense Ministry was delaying its budget request to evaluate when the F-35 would be produced and delivered.[300] David Howell of the UK Foreign Office has suggested that Japan could partner with Britain in the continuing development of the Eurofighter.[301] On 20 December 2011, the Japanese Government announced its intention to purchase 42 F-35s. The purchase decision was influenced by the F-35's stealth characteristics, with the Defence Minister Yasuo Ichikawa saying, "There are changes in the security environment and the actions of various nations and we want to have a fighter that has the capacity to cope".[302]

Norway

Norway considered purchasing the Eurofighter,[303] but in 2012 signed the largest public procurement project in the country's history (worth $10bn) for the F-35A.[304]

Qatar

From January 2011 the Qatar Emiri Air Force evaluated the Typhoon, alongside the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, the McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle, the Dassault Rafale, and the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, to replace its then inventory of Dassault Mirage 2000-5s. By June 2014, Dassault claimed it was close to signing a contract with Qatar for 72 Rafales.[305] On 30 April 2015, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani announced to President François Hollande that Qatar will order 24 Rafale with an option to buy 12 more aircraft, in a deal worth €6.3 billion (£5bn).[306] The contract was to be signed on 4 May 2015.[307][308]

Singapore

In 2005 the Eurofighter was a contender for Singapore's next generation fighter requirement competing with the Boeing F-15SG and the Dassault Rafale. The Eurofighter was eliminated from the competition in June 2005[309] and the F-15SG was selected in September 2005.[310]

South Korea

In 2002, the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) chose the F-15K Slam Eagle over the Dassault Rafale, Eurofighter Typhoon and Sukhoi Su-35 for its 40 aircraft F-X Phase I fighter competition. During 2012–13, the Typhoon competed with the Boeing F-15SE Silent Eagle and the F-35 for the ROKAF's F-X Phase III fighter competition. In August 2013 it was announced that the F-15SE was the only remaining candidate, however the award was cancelled and in November 2013, it was announced that the ROKAF will purchase 40 F-35A's.[311]

Switzerland

In February 2007, it was reported that Switzerland was considering the Eurofighter, the Rafale and the Saab JAS 39 Gripen to replace its Northrop F-5 Tiger IIs.[312] A one-month evaluation started in October 2008 at Emmen Airforce Base consisting of approximately 30 evaluation flights.[313] On 30 November 2011 the Swiss Federal Council announced that it was planning to buy 22 Gripen NGs due to its lower acquisition and maintenance costs.[314] A leaked Swiss Air Force evaluation report revealed that the Rafale won the competition on technical grounds and Dassault offered to lower the price for 18 Rafales.[315]

Turkey

Turkey was considering a purchase of Eurofighter, but in 2009 it decided to purchase a larger number of F-35s and it has subsequently stated that "Eurofighter is off Turkey's agenda".[316][317]

United Arab Emirates

In November 2012, the UK government announced the formation of a formal defence and industrial partnership with the United Arab Emirates, paving the way for potential Typhoon sales with BAE Systems.[318] On 19 December 2013 it was announced that UAE had decided not to proceed with the deal for the supply of defence and security services, including the supply of Typhoon aircraft.[319] Analysts estimated that the break-off was due to the producing nations' lack of commitment for radar upgrades.[320]

Variants

The Eurofighter is produced in single-seat and twin-seat variants. The twin-seat variant is not used operationally, but only for training, though it is combat capable. The aircraft has been manufactured in three major standards; seven Development Aircraft (DA), seven production standard Instrumented Production Aircraft (IPA) for further system development[321] and a continuing number of Series Production Aircraft. The production aircraft are now operational with the partner nation's air forces.

The Tranche 1 aircraft were produced from 2000 onwards. Aircraft capabilities are being increased incrementally, with each software upgrade resulting in a different standard, known as blocks.[322] With the introduction of the block 5 standard, the R2 retrofit programme began to bring all Tranche 1 aircraft to that standard.[322]

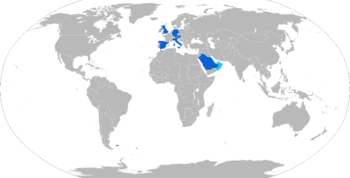

Operators

.jpg)

- Austrian Air Force – 15 delivered[323]

- German Air Force – 143 ordered, of which 125 had been delivered by June 2016.[325][326][327]

- Italian Air Force – 96 ordered, of which 82 have been delivered as of June 2016[325]

- 4º Stormo, Grosseto

- 36º Stormo, Gioia del Colle

- 37º Stormo, Trapani

- 18º Gruppo Caccia[324]

- Kuwait Air Force – 28 ordered.[259]

- Royal Air Force of Oman – 12 ordered.[328]

- Royal Saudi Air Force – 72 ordered, of which 60 have been delivered as of June 2016.[325]

- Spanish Air Force – 72 ordered, of which 61 have been delivered as of June 2016.[56][325]

- Ala 11, Seville-Morón Air Base

- Ala 14, Albacete-Los Llanos Air Base

- 142 Escuadrón[331]

- Royal Air Force – 160 ordered, of which 137 have been delivered by June 2013.[325][332][333]

- RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, England.

- No. 3 Squadron RAF[324]

- No. 11 Squadron RAF[324]

- No. 29 Squadron RAF, OCU Tactical pilot training and evaluation[324]

- No. 41 Squadron RAF, Test & Evaluation Squadron[334]

- RAF Lossiemouth, Moray, Scotland.

- No. 1 Squadron RAF[324]

- No. 2 Squadron RAF, from 1 April 2015.[335]

- No. 6 Squadron RAF[324]

- RAF Mount Pleasant, East Falkland, Falkland Islands

- Past Units.

- No. 17 Squadron RAF, OCU Tactical pilot training and evaluation[336]

- RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, England.

Accidents

By June 2014, there had been two fatal crashes in about 240,000 flight hours, flown by 406 aircraft, delivered to six different air forces.[337]

- On 21 November 2002, the Spanish twin-seat Typhoon prototype DA-6 crashed due to a double engine flameout caused by surges of the two engines at 45,000 ft. The two crew members escaped unhurt and the aircraft crashed in a military test range near Toledo, some 70 miles (110 km) from its base at Getafe Air Base.[338][339]

- On 23 April 2008 a Royal Air Force Typhoon FGR4 from 17 Squadron at RAF Coningsby, tail number ZJ943, made a wheels–up landing at the US Navy's NAS China Lake, in the United States.[340] The aircraft was severely damaged and was returned to the UK on 27 October 2008. It was stored in a hardened aircraft shelter at 11 Squadron for some time, before being stripped of most usable parts and moved to storage at RAF Shawbury on 29 July 2015.[341][342] The pilot from 17 Squadron did not sustain any significant injury. It is thought the pilot may have forgotten to deploy the undercarriage or that for some reason he was not alerted to the fact that the undercarriage was not deployed.[343][344] In July 2014, the Ministry of Defence revealed, under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act, that the remains of aircraft ZJ943 were held in storage at RAF Coningsby, although some parts had been lent to the Bloodhound SSC project.[345]