Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein

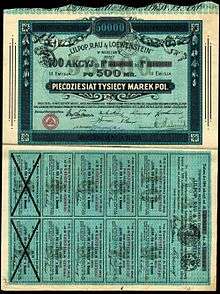

LRL logo was used alongside the full name until 1939 | |

1860 advertisement of the Lilpop factory | |

| Fate | destroyed by the Germans during World War II |

|---|---|

| Founded | Warsaw, Poland (1818) |

| Defunct | 1944 |

| Headquarters | Warsaw, Poland |

Number of employees |

ca. 150 in 1831 450 in 1866 1300 in 1897 ca. 2000 in 1914 3900 in 1938 |

Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein ([ˈlilpɔp rau̯ i lɛvɛnʂtai̯n], often shortened to Lilpop or LRL) was a Polish engineering company. Established in 1818 as an iron foundry, with time it rose to become a large holding company specialising in iron and steel production, as well as all sorts of machinery and metal products.

The largest factory was in Warsaw. Between the 1860s and World War II the company was the largest Polish producer of machinery, cars, lorries and railway equipment.[1] The range of products designed and produced by Lilpop included train engines, rails, railway cars and equipment for railroads, automotive engines, license-built lorries (Chevrolet and Buick), steam turbines, electric appliances and many other types of machinery.

The main factory of Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein in Warsaw was looted by the Germans during the World War II and the buildings demolished. The company was not rebuilt after the war.

History

Early years (1818–1855)

The predecessor to the Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein company was the Odlewnia i Rządowa Fabryka Machin ("Foundry and Government Machinery Factory"), the first iron foundry in Warsaw. Established in 1818, it was initially headed by Thomas Evans and Joseph Morris, two British nationals active in the Kingdom of Poland at the time. In 1824 Morris left the business and it was taken over by Thomas Evans and his brother Andrew,[2] hence it was renamed to "Bracia Evans" – the Evans Brothers Co. They were later joined by Douglas Evans, Alfred Evans and engineer Joshua Routledge. The company was producing mostly cast iron agricultural equipment and had a crew of approximately 150 workers.[2] Initially occupying a small plot of land at Piesza Street, soon it was moved to the ground of a former convent and a defrocked St. George's Church at Świętojerska Street.[2] A modern factory, it was the first venue in Warsaw to use gas lighting.[2]

During the November Uprising the factory extended its product range to include cannons for the Polish Army.[2] The company prospered until the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, when all British citizens, including Alfred and Douglas Evans, had to leave the Russian Empire and its dependencies.[3]

Soon before their departure in 1855 the Evans brothers invited two new people to the company: Wilhelm Rau and Stanisław Lilpop. Lilpop, a son of a watchmaker who had moved to Warsaw from Styria in the late 18th century, graduated from the Warsaw Piarist School in 1833 and joined the Evans Brothers company as a trainee.[3] A promising engineer, the Bank of Poland financed a scholarship for him and he was sent to Germany, England and France to train in steam engine construction.[3] Upon his return he took over the former State Machinery Factory (then headed by Wilhelm Rau, who continued to work for Lilpop), initially as its managing director and then as its owner.[3] Production of various agricultural machines of his own design, notably a reaper based on William Manning's design, allowed him to gather significant wealth and soon his firm was merged with that of the Evans brothers under a new name of "Evans, Lilpop et Comp." [3]

Rise to power (1855–1866)

The new company was now the first true concern in Poland: it owned not only the mechanical works in Warsaw, but also two iron ore mines and steel mills in Drzewica and Rozwady, both near Radom.[3] Lilpop modernised the production, turning the Warsaw plant from a simple manufactory to a modern, mechanised factory.[3] He also started cooperation with banks and introduced credit sale of his agricultural machines, a novelty in Poland at the time.[3] By 1866 the Warsaw factory included iron and brass foundries, along with mechanical workshops, all powered by a 40-horsepower steam engine.[3] That year the factory sold 22 steam engines and 1422 various machines for 360,000 roubles, the steel mills of Rozwady and Drzewica brought additional 300,000 in income.[3] The crew of the factory rose from 300 to 450 workers, plus 250 working in Rozwady and Drzewica.[3]

One of the best-selling products of the company was a reaper dubbed Amerykanka – The American, based on Lilpop's earlier designs. The reaper was very successful commercially (over 90 sold between 1857 and 1863 alone) and British Ransomes & Sims bought license for its production in the United Kingdom.[3] It received a silver medal at the 1867 International Exposition in Paris and remained in production almost until the end of the century.[3]

The company started producing equipment for railway companies, including rails and rail cars, notably for the Warsaw–Vienna railway. By 1866 Lilpop and Rau bought remaining shares of the Evans Brothers firm and renamed it to "Lilpop i Rau". Lilpop died later the same year in Biarritz,[3] but his widow, Joanna Lilpop, took over both his shares and his seat in the board.[4] She was the first, and for many years the only woman to hold a seat on the board of any large industrial firm in Poland.[4] She was later joined by their sons: Karol Lilpop (1849–1924), Wiktor Lilpop (1851–1922) and Marian Lilpop (1855–1889).[2]

Before the Great War (1866–1914)

After Lilpop's death, Bonawentura Toeplitz became the new general director and in 1868 Leon Loewenstein was invited into the partnership.[1][5] Loewenstein, a Jewish entrepreneur from Berlin, was both the nephew and son-in-law of Leopold Kronenberg, the richest banker, industrialist and railroad tycoon of Poland.[5] With Kronenberg's financial support (initially direct, later through his Commercial Bank), the then-renamed Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein company rose to become the largest industrial conglomerate of Poland, and one of largest companies of Imperial Russia.[5] Most importantly, both Jan Gotlib Bloch and Kronenberg placed huge orders for train engines and cars at the Lilpop factory, for their ever-expanding train empires.[5] Because of that, by 1877 Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein was responsible for over a quarter of all industrial production of Poland.[5] In addition, the company produced all sorts of iron and steel constructions, pipes, machinery, artillery shells, field kitchens and military equipment.[1][2]

A crisis came in 1877, when Russia turned to mercantilism to protect its own markets. High tariffs were imposed on import of, among others, coal, ores, iron and steel; also a customs boundary was created between Congress Poland and the rest of Russia. To counter the threat of being deprived of raw materials, in 1879 Lilpop company entered into a partnership with several bankers and turned their old iron foundry into a modern steel plant, the largest such factory in Poland.[6] Also, a gigantic iron-rolling mill was constructed shortly afterwards.[6] By the end of the century the total production of steel in the Kingdom of Poland rose from 18,000 tons in 1877 to 270,000 tons, with roughly a quarter produced by Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein.[6] In addition, the company opened new factories on the other side of the new customs boundary, in Bila Tserkva (until 1878) and Slavuta (until 1910).[1] It also had permanent trade offices in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Tbilisi, Odessa and Baku.[2]

In 1885 the factory was electrified as one of the first buildings in Warsaw, the company also started experimenting with arc welding, a novelty at the time.[7] By the end of the century the Warsaw plant alone had over 1300 workers.[2]

In 1905 Bonawentura Toeplitz died, having led the company for 39 years.[5] One of his last plans, completed over the next decade, was the move of the main factory and its main offices to a new, more modern venue at Bema Street.[2]

The last decades (1914–1945)

After the outbreak of World War I, in 1915 the factory, along with most of the staff (roughly 2000 workers in 1914),[2] was evacuated to Kremenchug by tsarist authorities.[8][1] There the equipment of the factory was captured by the Reds in the course of the Russian Civil War and only a small part was brought back to Warsaw after the Polish-Bolshevist War and the Peace of Riga.[1][2] The factory in Warsaw was nevertheless rebuilt and continued to prosper as one of principal industrial centres of the country.[1] Between 1921 and 1931 the factory was modernised and further expanded, extending the line of products by addition of internal combustion engines.[1] The Lilpop factory produced train engines, railway and tramway cars, bus bodies, lorry undercarriages (in cooperation with Hanomag), water turbines, industrial washing machines, rotodynamic pumps and many other products.[2]

In 1925 Lilpop factory introduced the Lilpop C electric tram, a reverse-engineered and slightly improved version of the ageing Typ A tram by a German consortium including Van der Zyper & Charlier, Siemens-Schuckert, MAN and Falkenried companies. While based on a tram first introduced 20 years before, the C type (bought in small numbers by the city of Warsaw) became the first in a long line of modern trams based on it, starting with Lilpop I (1927),[9] Lilpop II[10] and Lilpop LRL (1929),[11] Lilpop G (1932) and Lilpop III (1939).[12] The trams were in use in Łódź until 1973, some were also bought by other cities.[12]

In 1936 Lilpop also entered the automotive industry.[1] In the early 1930s the state-owned Państwowe Zakłady Inżynieryjne (PZInż) holding had a virtual state-imposed monopoly on assembling cars. The monopoly was lifted in 1936 and Lilpop immediately signed a contract with General Motors and Opel to assemble cars in their Warsaw and Lublin factories.[1] The decision to lift the monopoly led to entire leadership of PZInż resigning their positions.[13]

Car production at Lilpop started less than a year later, with a large portfolio of locally assembled cars. Among them were passenger cars of several brands: Buick (Buick 41 and Buick 90), Chevrolet (Chevrolet Master, Chevrolet Imperial and Chevrolet Sedan Taxi), Opel (Opel P4, Opel Kadett and Opel Olimpia). In addition, the company offered a number of utility cars and lorries, including Chevrolet 112 van, Chevrolet 121, 131 and Chevrolet 157 trucks and Chevrolet 183 bus. Between the world wars Poland was primarily an agricultural country, with an underdeveloped road network and high luxury taxes on cars. Because of that the overall volume of production remained low, with roughly 7000 cars and lorries assembled in Poland a year (data for 1938 and 1939). Most of those cars were assembled by Lilpop.[14][1]

In 1938 the factory had 3900 workers.[2] The same year the management started construction of a new car factory in Lublin that was to be completed in 1940 and was to take over the automotive part of the production. However, the war started before it could be completed.[2]

During World War II the factory was taken over by Nazi Germans and assigned to Reichswerke Hermann Göring and continued the production, this time for the Wehrmacht.[1] When the Warsaw Uprising broke out in 1944, the machinery was dismantled and sent to Germany, along with most of the workers.[1] Perhaps the single best-known car produced by LRL was a Chevrolet 157 3-ton truck named Kubuś, converted to an improvised armoured personnel carrier during the uprising. After the uprising the factory was levelled with explosives by German troops,[1] along with rest of the city. Only the office buildings survived the war.[2]

Legacy

After the war the new communist authorities of Poland nationalised virtually all privately held companies and there was no chance to rebuild the Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein company as a private venture. The remaining buildings at Bema Street continue to be used as offices. Perhaps the only part of the once powerful LRL concern that still exists is the Fabryka Samochodów Ciężarowych, the Lublin automotive branch of Lilpop, that was rebuilt after the war and continues to produce cars, notably the Tarpan Honker truck used by the Polish Army.[2] Another part of the pre-war concern that continued production after the war was FSC Star, until 1939 a partially owned subsidiary producing truck components for Lilpop-made Chevrolets.

Throughout its existence, the Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein company also trained many of the most important Polish engineers. Among those who collaborated with the company were Karol Adamiecki [8] and the pioneer of arc welding Stanisław Olszewski.[7] However, one of the best-known workers of Lilpop is Bolesław Prus, the famous Polish writer, who worked there for several years as an office clerk.[15]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 PWN, §1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Świątek, §1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Pilatowicz, pp. 139–142.

- 1 2 Mórawski, pp. 127, 130–131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marcus, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Marcus, p. 86.

- 1 2 Pilatowicz, pp. 180–181.

- 1 2 Pilatowicz, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Dębski, §Lilpop I.

- ↑ Dębski, §Lilpop II.

- ↑ Dębski, §Lilpop LRL.

- 1 2 Dębski, §Lilpop III.

- ↑ Pilatowicz, p. 126.

- ↑ Marcus, p. 118.

- ↑ Pieścikowski, pp. 19, 148.

References

- (Polish) Wojciech Dębski (2006). "Tabor tramwajowy" [Tramways]. Łódzkie tramwaje i autobusy. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- (Polish) Pieścikowski, Edward (1985). Bolesław Prus (2nd ed.). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 83-01-05593-6.

- (English) Joseph Marcus (1983). Social and Political History of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939. Studies in the social sciences. 37. Walter de Gruyter. p. 569. ISBN 9789027932396.

- (Polish) Karol Mórawski (1997). Leksykon wolski [The Lexicon of Wola]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo PTTK „Kraj”. ISBN 83-7005-389-0.

- (Polish) Józef Piłatowicz; Michał Czapski; Maciej Żak (2001). Józef Piłatowicz; Bolesław Orłowski, eds. Inżynierowie polscy w XIX i XX wieku [Polish engineers in 19th and 20th centuries] (PDF). T. 7: 100 najwybitniejszych polskich twórców techniki. Warsaw: Polskie Towarzystwo Historii Techniki. p. 285. ISBN 8387992151.

- (Polish) PWN (corporate author) (2013). "Towarzystwo Akcyjne Przemysłowe Zakładów Mechanicznych "Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein" SA". Słownik ekonomiczny PWN. Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN.

- (Polish) Tadeusz Władysław Świątek (2013). Magdalena Dobranowska-Wittels, ed. "Zakłady Metalurgiczne Lilpop, Rau i Loewenstein SA". Made in Wola. Retrieved 2014-04-12.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lilpop, Rau & Loewenstein. |