Exorcist II: The Heretic

| Exorcist II: The Heretic | |

|---|---|

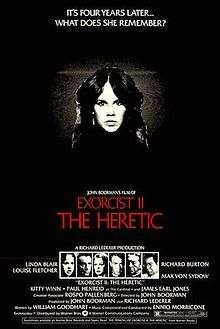

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Based on |

Characters by William Peter Blatty |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | William A. Fraker |

| Edited by | Tom Priestley |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $14 million |

| Box office | $30.7 million[2] |

Exorcist II: The Heretic is a 1977 American supernatural horror film directed by John Boorman and written by William Goodhart. It stars Linda Blair, Richard Burton, Louise Fletcher, Max von Sydow, Kitty Winn, Paul Henreid, and James Earl Jones. It is a sequel to William Friedkin's 1973 film The Exorcist based on the 1971 novel by William Peter Blatty, and part of The Exorcist franchise. The sequel is set four years after The Exorcist, and centers on a now 16-year-old Regan MacNeil who is still recovering from her previous demonic possession.

The film was a critical failure at the time of its release. The Heretic is often considered not just the worst film in the series, but one of the worst films of all time. It was the last film to feature veteran actor Paul Henreid.

Plot

Philip Lamont, a priest struggling with his faith, attempts to exorcise a possessed South American girl who claims to "heal the sick". However, the exorcism goes wrong and a lit candle sets fire to the girl's dress, killing her. Afterwards, Lamont is assigned by the Cardinal to investigate the death of Father Lankester Merrin, who had been killed four years prior in the course of exorcising the Assyrian demon Pazuzu from Regan MacNeil. The Cardinal informs Lamont (who has had some experience at exorcism, and has been exposed to Merrin's teachings) that Merrin is up on posthumous heresy charges due to his controversial writings. Apparently, Church authorities are trying to modernize and do not want to acknowledge that Satan actually exists.

Regan, although now seemingly normal and staying with guardian Sharon Spencer in New York, N.Y., continues to be monitored at a psychiatric institute by Dr. Gene Tuskin. Regan claims she remembers nothing about her ordeal in Washington, D.C., but Tuskin believes her memories are only repressed. Father Lamont visits the institute but his attempts to question Regan about the circumstances of Father Merrin's death are rebuffed by Dr. Tuskin, who believes that Lamont's approach would do Regan more harm than good. In an attempt to plumb her memories of the exorcism and specifically the circumstances in which Merrin died, Dr. Tuskin hypnotizes the girl, to whom she is linked by a "synchronizer" — a biofeedback device used by two people to synchronize their brainwaves. After a guided tour by Sharon of the Georgetown house where the exorcism took place, Lamont returns to be coupled with Regan by the synchronizer. The priest is spirited to the past by Pazuzu to observe Father Merrin exorcising a young boy, Kokumo, in Africa. Learning that the boy developed special powers to fight Pazuzu, who appears as a swarm of locusts, Lamont journeys to Africa, defying his superior, to seek help from the adult Kokumo.

Kokumo has become a scientist, studying how to prevent locust swarms. Lamont learns that Pazuzu attacks people who have psychic healing ability. Regan is able to reach telepathically inside the minds of others; she uses this to help an autistic girl to speak, for instance. Father Merrin, who belonged to a group of theologians that believed psychic powers were a spiritual gift which would one day be shared by all people, thought people like Kokumo and Regan were forerunners of this new type of humanity. In a vision, Merrin asks Lamont to watch over Regan.

Lamont and Regan return to the old house in Georgetown. The pair are followed in a taxi by Tuskin and Sharon, who are concerned about Regan's safety. En route, Pazuzu tempts Lamont by offering him unlimited power, appearing as a succubus doppelgänger of Regan. The taxi crashes into the Georgetown house, killing the driver, but his passengers survive and enter the house, where Sharon sets herself on fire. Although Lamont initially succumbs to the succubus, he is brought back by Regan and attacks her doppelgänger while a swarm of locusts deluge the house, which begins to crumble around them. However, Lamont manages to kill the doppelgänger by beating open its chest and pulling out its heart. In the end, Regan banishes the locusts (and Pazuzu) by enacting the same ritual attempted by Kokumo to get rid of locusts in Africa (although he failed and was himself possessed). Outside the house, Sharon dies from her injuries and Tuskin tells Lamont to watch over Regan. Regan and Lamont leave while Tuskin stays to answer police questions.

Cast

- Linda Blair as Regan MacNeil

- Richard Burton as Father Philip Lamont

- Louise Fletcher as Dr. Gene Tuskin

- Max von Sydow as Father Lankester Merrin

- Kitty Winn as Sharon Spencer

- Paul Henreid as The Cardinal

- James Earl Jones as Kokumo

- Joey Green as young Kokumo

- Ned Beatty as Edwards

- Belinda Beatty as Liz

- Barbara Cason as Mrs. Phalor

- Ken Renard as Abbot

- Dana Plato as Sandra Phalor

- Karen Knapp as the voice of Pazuzu

Production

Development

Neither William Peter Blatty nor William Friedkin—the writer/producer and the director, respectively, of the original Exorcist—had any desire to involve themselves in an Exorcist sequel.[3] According to the film's co-producer Richard Lederer, Exorcist II was conceived as a relatively low-budget affair: "What we essentially wanted to do with the sequel was to redo the first movie... Have the central figure, an investigative priest, interview everyone involved with the exorcism, then fade out to unused footage, unused angles from the first film. A low-budget rehash — about $3 million — of The Exorcist, a rather cynical approach to movie-making, I'll admit. But that was the start."[3]

Playwright William Goodhart was commissioned to write the screenplay, titled The Heretic, and based it around the theories of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (the Jesuit paleontologist/archaeologist who inspired the character of Father Merrin when Blatty wrote The Exorcist). Goodhart's screenplay took a more metaphysical and intellectual approach compared to the original film. That the battle between good and evil would this time centre around human consciousness. Specifically, that, within the framework of Catholic theology, that human consciousness could be brought together as one through technology, though that it would also result in conflict between those who sought good and evil.[4]

British filmmaker Boorman signed on to direct, stating that "the idea of making a metaphysical thriller greatly appealed to my psyche".[5] Years before, Boorman had been considered by Warner Bros. as a possible director for the first Exorcist movie, but he turned the opportunity down as he found the story "rather repulsive."[5] Boorman, however, was intrigued with the idea of directing a sequel, explaining that "every film has to struggle to find a connection with its audience. Here I saw the chance to make an extremely ambitious film without having to spend the time developing this connection. I could make assumptions and then take the audience on a very adventurous cinematic journey."[5]

Casting

Blair agreed to reprise her role of Regan MacNeil for Exorcist II, but refused to wear demon make-up (a double was used for the brief flashback scenes depicting a demonic Regan). Von Sydow was persuaded by Boorman to reprise the role of Father Merrin; he was initially reluctant to return because of his concerns over the negative impact of the first Exorcist film. Winn signed on to reprise the role of Sharon Spencer for Exorcist II after Ellen Burstyn flatly refused to return as Chris MacNeil.

Boorman contacted William O'Malley to reprise his role as Father Joseph Dyer from the first film. However, O'Malley was busy and could not take up the part, and the character of Father Dyer was changed to Father Philip Lamont. Jon Voight, David Carradine, Jack Nicholson and Christopher Walken all were considered or offered the part of Father Lamont, who John Boorman initially conceived as a younger priest in awe of Father Merrin's writings. Eventually the choice was made to age the character, and Richard Burton was signed for the role.

The role of Dr. Gene Tuskin was originally written for a man, with Chris Sarandon and George Segal both considered. When the sex of the character was changed, both Ann-Margret and Jane Fonda were under consideration. Louise Fletcher, who had just won the Academy Award for Best Actress for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), accepted the part.

Screenplay and filming

Principal photography began May 1976, at a budget of $12.5 million (the film ultimately cost $14 million to make). Although Boorman wanted to film the majority of the film on location (including Ethiopia and The Vatican), many of Boorman's plans proved to be impossible, resulting in key exterior scenes having to be filmed set-bound at the Warner Bros. backlot. Even the MacNeil house in Georgetown had to be replicated in the studio, as the filmmakers were refused permission to film at the original house. The filmmakers also had to replicate the infamous "Hitchcock Steps" adjacent to the MacNeil house, as they were refused permission by Washington city officials to shoot scenes by the real steps.[6] A key scene of a sleepwalking Regan about to wander off a rooftop was filmed in New York atop 666 Fifth Avenue (where Warner Bros. offices were then located). With no stunt person and no special effects, the shot showed Linda Blair's feet on the edge of the building with Fifth Avenue down below.[7]

Boorman was unhappy with Goodhart's script, and asked Goodhart to do a rewrite, incorporating ideas from Rospo Pallenberg. Goodhart refused, and so the script was subsequently rewritten by Pallenberg and Boorman. Goodhart's script was being constantly rewritten as the film was shooting, with the filmmakers uncertain as to how the story should end. Actress Linda Blair recalled "It was a really good script at first. Then after everybody signed on they rewrote it five times and it ended up nothing like the same movie."[8]

Exorcist II was beset by numerous problems during production. Boorman himself contracted a dose of San Joaquin Valley Fever (a respiratory fungal infection), which cancelled production for over a month (a costly delay). Other problems included footage being over-saturated and necessitating re-shoots, the rapid deaths of locusts imported from England for the film’s climactic scenes (2500 locusts were shipped in, and died at a rate of 100 a day); original film editor John Merritt quitting the production (replaced by Tom Priestley); and stars Kitty Winn and Louise Fletcher both suffering from gall bladder infections.[9]

One of the key elements of The Heretic is Merrin's exorcism of a young boy named "Kokumo" in Africa. This exorcism is first referenced in the original film The Exorcist, and actually illustrated with flashbacks in Exorcist II: The Heretic. Although this same exorcism becomes the central plot line for the most recent Exorcist movies Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist and Exorcist: The Beginning, little effort was made to keep the stories consistent. The boy is not named Kokumo, and the locations and circumstances of the exorcism do not resemble Exorcist II: The Heretic even remotely. Ultimately we learn from Exorcist: The Beginning that the African boy is not the one actually afflicted; it turns out to be another character entirely that is possessed.

According to Blair in one interview, Pallenberg directed a lot of the film, as well as doing re-writes.[10] Pallenberg was credited as the second unit director and a "creative associate".

Release

Box office

The Heretic was a disappointment at the box office. The film eventually grossed $30,749,142 in the United States,[2] turning a profit but still disappointing in comparison to the original film's gross.

Critical reception

The film received a strongly negative response. Reports indicated that the film inspired derisive audience laughter at its premiere in New York City.[11] William Peter Blatty claimed to have been the first person to start laughing at the theater at which he saw the film, only to be followed by the other patrons ("You'd think we were watching The Producers"[12] William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist, recalled hearing a story in which angry audience members at Exorcist II's first public performance began chasing Warner Bros. executives down the street within the first ten minutes of the screening).[13] Friedkin saw half an hour of the film, "I was at Technicolor and a guy said 'We just finished a print of Exorcist II, do you wanna have a look at it?' And I looked at half an hour of it and I thought it was as bad as seeing a traffic accident in the street. It was horrible. It's just a stupid mess made by a dumb guy – John Boorman by name, somebody who should be nameless, but in this case should be named. Scurrilous. A horrible picture."[8] Friedkin later stated that this sequel diminished the value of the original and called it "one of the worst films I've ever seen".[14]

Variety wrote, "Exorcist II is not as good as The Exorcist. It isn't even close." BBC film critic Mark Kermode stated "Exorcist II is demonstrably the worst film ever made. It took the greatest film ever made and trashed it in a way that was on one level farcically stupid and on another level absolutely unforgivable. Everyone involved in this, apart from Linda Blair, should be ashamed for all eternity." The New York Times agreed, writing "Given the huge box-office success of the William Peter Blatty-William Friedkin production of The Exorcist, there had to be a sequel, but did it have to be this desperate concoction, the main thrust of which is that original exorcism wasn't all it was cracked up to be? It's one thing to carry a story further along, but it's another to deny the original, no matter what you thought of it. I thought it was something even less than good, but this new film, which opened yesterday at the Criterion and other theaters, is of such spectacular fatuousness that it makes the first seem virtually an axiom of screen art." John Simon wrote in National Review, "There is a very strong probability that Exorcist II is the stupidest major movie ever made," and Jack Lewis wrote in The Daily Mirror, "It's all too ludicrous to frighten and the only time you're likely to hide your head will be in shame for watching it."[15]

Leslie Halliwell described the film as a "highly unsatisfactory psychic melodrama which...falls flat on its face along some wayward path of metaphysical and religious fancy. It was released in two versions and is unintelligible in either."[16] Leonard Maltin described the film as a "preposterous sequel...Special effects are the only virtue in this turkey."[17] Steven Scheuer wrote, "This may be the worst sequel in the history of film."[18] Danny Peary dismissed Exorcist II as "absurd."[19] In his 1984 book The Hollywood Hall of Shame, Michael Medved called the film "a thoroughly wretched piece of work," and added, "Richard Burton is a laugh a minute."[20] Edward Margulies called the film a "calamitious, head-scratching, sequel..a rollicking mess" and wondered "whatever possessed them?"[21] The Blockbuster Entertainment Guide to Movies & Videos gave this film its lowest possible rating and dismissed its story as "the expected demonic shenanigans"[22]

However, Pauline Kael preferred Boorman's sequel to the original, writing in her review in The New Yorker that Exorcist II "had more visual magic than a dozen movies." Kim Newman commented that "Exorcist II doesn't work in all sorts of ways... However, like Ennio Morricone's mix of tribal and liturgical music, it does manage to be very interesting."[23] Director Martin Scorsese asserted, "The picture asks: Does great goodness bring upon itself great evil? This goes back to the Book of Job; it's God testing the good. In this sense, Regan (Linda Blair) is a modern-day saint — like Ingrid Bergman in Europa '51, and in a way, like Charlie in Mean Streets. I like the first Exorcist, because of the Catholic guilt I have, and because it scared the hell out of me; but The Heretic surpasses it. Maybe Boorman failed to execute the material, but the movie still deserved better than it got."[24]

Author Bob McCabe's book The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows contains a chapter on the film in which Linda Blair said the movie "was one of the big disappointments of my career,"[8] and John Boorman confessed that "The sin I committed was not giving the audience what it wanted in terms of horror...There's this wild beast out there which is the audience. I created this arena and I just didn't throw enough Christians into it."[25] McCabe himself offered no one answer as to why Exorcist II failed: "Who knows where the blame ultimately lies? Boorman's illness and constant revising of the script can't have helped, but these events alone are not enough to explain the film's almighty failure. Boorman has certainly gone on to produce some fine work subsequently... When a list was compiled for The 50 Worst Movies Ever Made, Exorcist II: The Heretic came in at number two. It was beaten only by Ed Wood's Plan 9 from Outer Space, a film that generally receives a warmer response from its audience than this terribly misjudged sequel."[8] In a 2005 interview, John Boorman remarked:

it all comes down to audience expectations. The film that I made, I saw as a kind of riposte to the ugliness and darkness of The Exorcist – I wanted a film about journeys that was positive, about good, essentially. And I think that audiences, in hindsight, were right. I denied them what they wanted and they were pissed off about it – quite rightly, I knew I wasn't giving them what they wanted and it was a really foolish choice. The film itself, I think, is an interesting one – there's some good work in it – but when they came to me with it I told John Calley, who was running Warner Bros. then, that I didn't want it. "Look," I said, "I have daughters, I don't want to make a film about torturing a child," which is how I saw the original film. But then I read a three-page treatment for a sequel written by a man named William Goodhart and I was really intrigued by it because it was about goodness. I saw it then as a chance to film a riposte to the first picture. But it had one of the most disastrous openings ever – there were riots! And we recut the actual prints in the theatres, about six a day, but it didn't help of course and I couldn't bear to talk about it, or look at it, for years.[26]

Accolades

Both Blair and Burton received Saturn Award nominations for Best Actress and Best Actor.

References

- ↑ "EXORCIST II - THE HERETIC (X)". British Board of Film Classification. July 26, 1977. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- 1 2 "Box Office Information for Exorcist II: The Heretic". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- 1 2 McCabe 2000, p. 156.

- ↑ Pallenberg 1977, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 McCabe 2000, p. 158.

- ↑ Bob McCabe, The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows (Omnibus Press, 1999), pp. 160-162

- ↑ Pallenberg, Barbara. The Making of Exorcist II: The Heretic. New York City, Warner Books, 1977.

- 1 2 3 4 McCabe 2000, p. 165.

- ↑ Bob McCabe, The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows (Omnibus Press, 1999), pp. 160-163

- ↑ "Linda Blair reflects on the Devil inside in a new interview".

- ↑ Muir 2002, p. 475.

- ↑ McCabe 2000, p. 163.

- ↑ Interview with William Friedkin at the Chicago Critics Film Festival, April 14, 2013.

- ↑ Don Kaye. "Exorcist director says sequel is 'one of the worst films I've ever seen'". Blastr. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ "Exorcist II: The Heretic". movie-film-review.com. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Halliwell 1995, p. 370.

- ↑ Maltin 2008, p. 427.

- ↑ Scheuer 1986, p. 323.

- ↑ Peary 1986, p. 143.

- ↑ Medved 1984.

- ↑ Margulies 1993, p. 201.

- ↑ Castell 1997, p. 341.

- ↑ Newman 2011, p. 63.

- ↑ Scorsese, Martin. "Martin Scorsese's Guility Pleasures", Film Comment, September/October 1998

- ↑ McCabe 2000, p. 164.

- ↑ Filmfreakcentral.net

Bibliography

- Halliwell, Leslie (1995). Halliwell's Film Guide (Fifth ed.). Harper Collins.

- Maltin, Leonard (2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. Plume. ISBN 978-0-45122-468-2.

- McCabe, Bob (2000). The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-71197-509-5.

- Medved, Michael (1984). Hollywood Hall of Shame: The Most Expensive Flops in Movie History. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-39950-714-4.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78649-156-8.

- Newman, Kim (2011). Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-40880-503-9.

- Pallenberg, Barbara (1977). The Making of Exorcist II: The Heretic. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-44689-361-9.

- Peary, Danny (1986). Guide for the Film Fanatic. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-67161-081-4.

- Scheuer, Steven (1991). Movies on TV and Videocassette. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-55329-147-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Exorcist II: The Heretic |

- Official website

- Exorcist II: The Heretic at the Internet Movie Database

- Exorcist II: The Heretic at Box Office Mojo

- Exorcist II: The Heretic at Rotten Tomatoes