Exxon Valdez oil spill

| Exxon Valdez oil spill | |

|---|---|

|

3 days after Exxon Valdez ran aground | |

| Location | Prince William Sound, Alaska |

| Coordinates | 60°50′27″N 146°51′45″W / 60.8408°N 146.8625°WCoordinates: 60°50′27″N 146°51′45″W / 60.8408°N 146.8625°W |

| Date | March 24, 1989 |

| Cause | |

| Cause | Grounding of the Exxon Valdez oil tanker |

| Operator | Exxon |

| Spill characteristics | |

| Volume | 260,000–750,000 bbl (41,000–119,000 m3) |

| Area | 11,000 sq mi (28,000 km2) |

| Shoreline impacted | 1,300 mi (2,100 km) |

The Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred in Prince William Sound, Alaska, on Good Friday, March 24, 1989, when Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker bound for Long Beach, California, struck Prince William Sound's Bligh Reef at 12:04 am[1][2] local time and spilled 11 to 38 million US gallons (260,000 to 900,000 bbl; 42,000 to 144,000 m3) of crude oil[3][4] over the next few days. It is considered to be one of the most devastating human-caused environmental disasters.[5] The Valdez spill was the largest in US waters until the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, in terms of volume released.[6] However, Prince William Sound's remote location, accessible only by helicopter, plane, or boat, made government and industry response efforts difficult and severely taxed existing plans for response. The region is a habitat for salmon, sea otters, seals and seabirds. The oil, originally extracted at the Prudhoe Bay oil field, eventually covered 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of coastline,[7] and 11,000 square miles (28,000 km2) of ocean.[8]

According to official reports, the ship was carrying approximately 55 million US gallons (210,000 m3) of oil, of which about 10.1 to 11 million US gallons (240,000 to 260,000 bbl; 38,000 to 42,000 m3) were spilled into the Prince William Sound.[1][9] A figure of 11 million US gallons (260,000 bbl; 42,000 m3) was a commonly accepted estimate of the spill's volume and has been used by the State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council,[7] the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and environmental groups such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club.[6][10][11] Some groups, such as Defenders of Wildlife, dispute the official estimates, maintaining that the volume of the spill, which was calculated by subtracting the volume of material removed from the vessel's tanks after the spill from the volume of the original cargo, has been underreported.[12] Alternative calculations, based on the assumption that the official reports underestimated how much seawater had been forced into the damaged tanks, placed the total at 25 to 32 million US gallons (600,000 to 760,000 bbl; 95,000 to 121,000 m3).[3]

Identified causes

Multiple factors have been identified as contributing to the incident:

- Exxon Shipping Company failed to supervise the master and provide a rested and sufficient crew for Exxon Valdez. The NTSB found this was widespread throughout the industry, prompting a safety recommendation to Exxon and to the industry.[14]

- The third mate failed to properly maneuver the vessel, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload.[14]

- Exxon Shipping Company failed to properly maintain the Raytheon Collision Avoidance System (RAYCAS) radar, which, if functional, would have indicated to the third mate an impending collision with the Bligh Reef by detecting the "radar reflector", placed on the next rock inland from Bligh Reef for the purpose of keeping ships on course. This cause has only been identified by Greg Palast (without evidentiary support) and is not present in the official accident report.[15]

Captain Joseph Hazelwood, who was widely reported to have been drinking heavily that night, was not at the controls when the ship struck the reef. However, as the senior officer, he was in command of the ship even though he was asleep in his bunk. In light of the other findings, investigative reporter Greg Palast stated in 2008, "Forget the drunken skipper fable. As to Captain Joe Hazelwood, he was below decks, sleeping off his bender. At the helm, the third mate never would have collided with Bligh Reef had he looked at his RAYCAS radar. But the radar was not turned on. In fact, the tanker's radar was left broken and disabled for more than a year before the disaster, and Exxon management knew it. It was [in Exxon's view] just too expensive to fix and operate." [16] Exxon blamed Captain Hazelwood for the grounding of the tanker.[15]

Other factors, according to an MIT course entitled "Software System Safety" by Professor Nancy G. Leveson,[17] included:

- Ships were not informed that the previous practice of the Coast Guard tracking ships out to Bligh Reef had ceased.[18]

- The oil industry promised, but never installed, state-of-the-art iceberg monitoring equipment.[19]

- Exxon Valdez was sailing outside the normal sea lane to avoid small icebergs thought to be in the area.[19]

- The 1989 tanker crew was half the size of the 1977 crew, worked 12- to 14-hour shifts, plus overtime. The crew was rushing to leave Valdez with a load of oil.[20]

- Coast Guard vessel inspections in Valdez were not performed, and the number of staff was reduced.[20]

- Lack of available equipment and personnel hampered the spill cleanup.[18]

This disaster resulted in International Maritime Organization introducing comprehensive marine pollution prevention rules (MARPOL) through various conventions. The rules were ratified by member countries and, under International Ship Management rules, the ships are being operated with a common objective of "safer ships and cleaner oceans".

In 2009, Exxon Valdez Captain Joseph Hazelwood offered a "heartfelt apology" to the people of Alaska, suggesting he had been wrongly blamed for the disaster: "The true story is out there for anybody who wants to look at the facts, but that's not the sexy story and that's not the easy story," he said.[21] Yet Hazelwood said he felt Alaskans always gave him a fair shake.

Clean-up and environmental impact

Chemical dispersant, a surfactant and solvent mixture, was applied to the slick. A private company applied dispersant on March 24 with a helicopter and dispersant bucket. Because there was not enough wave action to mix the dispersant with the oil in the water, the use of the dispersant was discontinued.[22] An aerial dispersant application also missed its target, hitting the tanker itself, a Coast Guard vessel and its crew.[23]

One trial explosion was also conducted during the early stages of the spill to burn the oil, in a region of the spill isolated from the rest by another explosion. This attempt is believed to have led to many health problems for a neighboring native village that was downwind of the fumes caused by the explosion.[24] The test was relatively successful, reducing 113,400 liters of oil to 1,134 liters of removable residue, but because of the health consequences, no additional burning was attempted.[22][25]

The dispersant Corexit 9580 was formulated in response to the spill for potential shore cleanup operations and trialed on Smith, Disk and Eleanor islands in 1989[26] and the "heavily oiled" Knight Island in 1990.[27] Its wider use was not permitted owing to Government and public concerns about its toxicity.

According to the booklet Shoreline Treatment Techniques published in 1993 by the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, while it effectively assisted in clean-up, "It had not been tested, scientific data on its toxicity were either thin or incomplete, and it had operational problems. In addition, public acceptance of a new, widespread chemical treatment was lacking. To landowners, fishing groups, and conservation organizations, the idea of dumping chemicals on hundreds of miles of shorelines that had just been oiled seemed much too risky - especially when there were other alternatives."[25][28][28][29]

According to a report by David Kirby for TakePart, the main component of the Corexit formulation used during cleanup, 2-butoxyethanol, was identified as "one of the agents that caused liver, kidney, lung, nervous system, and blood disorders among cleanup crews in Alaska following the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill.[30]

Mechanical cleanup was started shortly afterwards using booms and skimmers, but the skimmers were not readily available during the first 24 hours following the spill, and thick oil and kelp tended to clog the equipment. Despite civilian insistence for a complete clean, only 10% of total oil was actually completely cleaned.[1] Exxon was widely criticized for its slow response to cleaning up the disaster and John Devens, the mayor of Valdez, has said his community felt betrayed by Exxon's inadequate response to the crisis.[31] More than 11,000 Alaska residents, along with some Exxon employees, worked throughout the region to try to restore the environment.

Because Prince William Sound contained many rocky coves where the oil collected, the decision was made to displace it with high-pressure hot water. However, this also displaced and destroyed the microbial populations on the shoreline; many of these organisms (e.g. plankton) are the basis of the coastal marine food chain, and others (e.g. certain bacteria and fungi) are capable of facilitating the biodegradation of oil. At the time, both scientific advice and public pressure was to clean everything, but since then, a much greater understanding of natural and facilitated remediation processes has developed, due somewhat in part to the opportunity presented for study by the Exxon Valdez spill. Despite the extensive cleanup attempts, less than ten percent of the oil was recovered and a study conducted by NOAA determined that as of early 2007 more than 26 thousand U.S. gallons (98 m3) of oil remain in the sandy soil of the contaminated shoreline, declining at a rate of less than 4% per year.[32][33]

Both the long-term and short-term effects of the oil spill have been studied.[34] Immediate effects included the deaths of 100,000 to as many as 250,000 seabirds, at least 2,800 sea otters, approximately 12 river otters, 300 harbor seals, 247 bald eagles, and 22 orcas, and an unknown number of salmon and herring.[9][35]

In 2003, fifteen years after the spill, a team from the University of North Carolina found that the remaining oil was lasting far longer than anticipated, which in turn had resulted in more long-term loss of many species than had been expected. The researchers found that at only a few parts per billion, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons caused a long-term increase in mortality rates. They reported that "species as diverse as sea otters, harlequin ducks and killer whales suffered large, long-term losses and that oiled mussel beds and other tidal shoreline habitats will take an estimated 30 years to recover."[36]

In 2006, a study done by the National Marine Fisheries Service in Juneau found that about 6 miles (9.7 km) of shoreline around Prince William Sound was still affected by the spill, with 101.6 tonnes of oil remaining in the area. Exxon Mobil denied any concerns over any remaining oil, stating that they anticipated a remaining fraction that they assert will not cause any long-term ecological impacts, according to the conclusions of the studies they had done: "We've done 350 peer-reviewed studies of Prince William Sound, and those studies conclude that Prince William Sound has recovered, it's healthy and it's thriving."[37] However, in 2007 a NOAA study concluded that this contamination can produce chronic low-level exposure, discourage subsistence where the contamination is heavy, and decrease the "wilderness character" of the area.[33]

The effects of the spill continued to be felt for many years afterwards. As of 2010 there were an estimated 23,000 US gallons (87 m3) of Valdez crude oil still in Alaska's sand and soil, breaking down at a rate estimated at less than 4% per year.[38]

On March 24, 2014, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the spill, NOAA scientists reported that some species seem to have recovered, with the sea otter the latest creature to return to pre-spill numbers. Scientists who have monitored the spill area for the last 25 years report that concern remains for one of two pods of local orca whales, with fears that one pod may eventually die out.[39] Federal scientists estimate that between 16,000 and 21,000 gallons of oil remains on beaches in Prince William Sound and up to 450 miles (725 km) away. Some of the oil does not appear to have biodegraded at all. A USGS scientist who analyses the remaining oil along the coastline states that it remains among rocks and between tide marks. "The oil mixes with seawater and forms an emulsion...Left out, the surface crusts over but the inside still has the consistency of mayonnaise – or mousse." [40] Alaska state senator Berta Gardner is urging Alaskan politicians to demand that the US government force ExxonMobil to pay the final $92 million (£57 million) still owed from the court settlement. The major part of the money would be spent to finish cleaning up oiled beaches and attempting to restore the crippled herring population.[40]

Litigation and cleanup costs

In the case of Exxon v. Baker, an Anchorage jury awarded $287 million for actual damages and $5 billion for punitive damages. To protect itself in case the judgment was affirmed, Exxon obtained a $4.8 billion credit line from J.P. Morgan & Co. J.P. Morgan created the first modern credit default swap in 1994, so that Morgan's would not have to hold as much money in reserve (8% of the loan under Basel I) against the risk of Exxon's default.[41]

Meanwhile, Exxon appealed the ruling, and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the original judge, Russel Holland, to reduce the punitive damages. On December 6, 2002, the judge announced that he had reduced the damages to $4 billion, which he concluded was justified by the facts of the case and was not grossly excessive. Exxon appealed again and the case returned to court to be considered in light of a recent Supreme Court ruling in a similar case, which caused Judge Holland to increase the punitive damages to $4.5 billion, plus interest.

After more appeals, and oral arguments heard by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals on January 27, 2006, the damages award was cut to $2.5 billion on December 22, 2006. The court cited recent Supreme Court rulings relative to limits on punitive damages.[42]

Exxon appealed again. On May 23, 2007, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals denied ExxonMobil's request for a third hearing and let stand its ruling that Exxon owes $2.5 billion in punitive damages. Exxon then appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case.[43] On February 27, 2008, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for 90 minutes. Justice Samuel Alito, who at the time, owned between $100,000 and $250,000 in Exxon stock, recused himself from the case.[44] In a decision issued June 25, 2008, Justice David Souter issued the judgment of the court, vacating the $2.5 billion award and remanding the case back to the lower court, finding that the damages were excessive with respect to maritime common law. Exxon's actions were deemed "worse than negligent but less than malicious."[45] The punitive damages were further reduced to an amount of $507.5 million.[46] The Court's ruling was that maritime punitive damages should not exceed the compensatory damages,[46] supported by a peculiar precedent dating back from 1818.[47] Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick J. Leahy has decried the ruling as "another in a line of cases where this Supreme Court has misconstrued congressional intent to benefit large corporations."[48]

Exxon's official position was that punitive damages greater than $25 million were not justified because the spill resulted from an accident, and because Exxon spent an estimated $2 billion cleaning up the spill and a further $1 billion to settle related civil and criminal charges. Attorneys for the plaintiffs contended that Exxon bore responsibility for the accident because the company "put a drunk in charge of a tanker in Prince William Sound."[49]

Exxon recovered a significant portion of clean-up and legal expenses through insurance claims associated with the grounding of the Exxon Valdez.[50][51] Also, in 1991, Exxon made a quiet, separate financial settlement of damages with a group of seafood producers known as the Seattle Seven for the disaster's effect on the Alaskan seafood industry. The agreement granted $63.75 million to the Seattle Seven, but stipulated that the seafood companies would have to repay almost all of any punitive damages awarded in other civil proceedings. The $5 billion in punitive damages was awarded later, and the Seattle Seven's share could have been as high as $750 million if the damages award had held. Other plaintiffs have objected to this secret arrangement,[52] and when it came to light, Judge Holland ruled that Exxon should have told the jury at the start that an agreement had already been made, so the jury would know exactly how much Exxon would have to pay.[53]

As of December 15, 2009, Exxon paid all owed $507.5 million punitive damages, including lawsuit costs, plus interest, which were further distributed to thousands of plaintiffs.[54]

In October 1989, Exxon filed suit against the State of Alaska, charging that the government had interfered with Exxon's attempts to clean up the spill by refusing to approve the use of dispersant chemicals until the night of the 26th. The government disputed the claim, stating that there was a long-standing agreement to allow the use of dispersants to clean up spills, thus Exxon did not require permission to use them, and that in fact Exxon had not had enough dispersant on hand to effectively handle a spill of the size created by the Valdez. [55] Exxon filed claims in October 1990 against the Coast Guard, asking to be reimbursed for cleanup costs and damages awarded to plaintiffs in any lawsuits filed by the State of Alaska or the Federal Government against Exxon. The company claimed that the Coast Guard was "wholly or partially responsible" for the spill, because they had granted mariners' licenses to the crew of the Valdez, and because they had given he Valdez permission to leave regular shipping lanes to avoid ice. They also reiterated the claim that the Coast Guard had delayed cleanup by refusing to give permission to use chemical dispersants on the spill immediately.[56]

Political consequences and reforms

Coast Guard report

A report by the US National Response Team summarized the event and made a number of recommendations, such as changes to the work patterns of Exxon crew in order to address the causes of the accident.[1]

Oil Pollution Act of 1990

In response to the spill, the United States Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). The legislation included a clause that prohibits any vessel that, after March 22, 1989, has caused an oil spill of more than 1 million US gallons (3,800 m3) in any marine area, from operating in Prince William Sound.[57]

In April 1998, the company argued in a legal action against the Federal government that the ship should be allowed back into Alaskan waters. Exxon claimed OPA was effectively a bill of attainder, a regulation that was unfairly directed at Exxon alone.[58] In 2002, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Exxon. As of 2002, OPA had prevented 18 ships from entering Prince William Sound.[59]

OPA also set a schedule for the gradual phase in of a double hull design, providing an additional layer between the oil tanks and the ocean. While a double hull would likely not have prevented the Valdez disaster, a Coast Guard study estimated that it would have cut the amount of oil spilled by 60 percent.[60]

The Exxon Valdez supertanker was towed to San Diego, arriving on July 10. Repairs began on July 30. Approximately 1,600 short tons (1,500 t) of steel were removed and replaced. In June 1990 the tanker, renamed S/R Mediterranean, left harbor after $30 million of repairs.[59] It was still sailing as of January 2010, registered in Panama. The vessel was then owned by a Hong Kong company, who operated it under the name Oriental Nicety. In August 2012, it was beached at Alang, India and dismantled.

Alaska regulations

In the aftermath of the spill, Alaska governor Steve Cowper issued an executive order requiring two tugboats to escort every loaded tanker from Valdez out through Prince William Sound to Hinchinbrook Entrance. As the plan evolved in the 1990s, one of the two routine tugboats was replaced with a 210-foot (64 m) Escort Response Vehicle (ERV). Tankers at Valdez are no longer single-hulled. Congress enacted legislation requiring all tankers to be double-hulled as of 2015.

Economic and personal impact

In 1991, following the collapse of the local marine population (particularly clams, herring and seals) the Chugach Alaska Corporation, an Alaska Native Corporation, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. It has since recovered.[61]

According to several studies funded by the state of Alaska, the spill had both short-term and long-term economic effects. These included the loss of recreational sports, fisheries, reduced tourism, and an estimate of what economists call "existence value", which is the value to the public of a pristine Prince William Sound.[62][63][64]

The economy of the city of Cordova, Alaska was adversely affected after the spill damaged stocks of salmon and herring in the area.

In 2010, a CNN report alleged that many oil spill cleanup workers involved in the Exxon Valdez response had subsequently become sick. Anchorage lawyer Dennis Mestas found that this was true of 6,722 of 11,000 worker files he was able to inspect. Access to the records was controlled by Exxon. Exxon responded in a statement to CNN:

"After 20 years, there is no evidence suggesting that either cleanup workers or the residents of the communities affected by the Valdez spill have had any adverse health effects as a result of the spill or its cleanup."[65][66]

Reactions

In 1992, Exxon released a video titled Scientists and the Alaska Oil Spill, to be distributed to schools. Dr. Michael Fry called it a piece of "corporate propaganda".[67]

In December 1994, the Unabomber assassinated Burson-Marsteller executive Thomas Mosser, accusing him of having "helped Exxon clean up its public image after the Exxon Valdez incident". The PR company claimed not to have been contracted during the actual crisis.[68]

See also

- List of oil spills

- Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Ixtoc I oil spill

- Dead Ahead: The Exxon Valdez Disaster, 1992 HBO movie

- Into Great Silence: A memoir of discovery and loss among vanishing Orcas. Eva Saulitis: Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, Copyright 2013

References

- 1 2 3 4 Skinner, Samuel K; Reilly, William K. (May 1989). The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: A Report to the President (PDF). National Response Team. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: Spill Timeline

- 1 2 Elizabeth Bluemink (June 10, 2010). "Size of Exxon spill remains disputed". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ↑ Riki Ott (June 18, 2010). "How Much Oil Really Spilled From the Exxon Valdez?". On The Media (Interview: audio/transcript). Interview with Brooke Gladstone. National Public Radio. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About the Spill". Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- 1 2 Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (September 1992). "Oil Spill Case Histories 1967–1991, Report No. HMRAD 92-11" (PDF). Seattle: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 80. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- 1 2 "Questions and Answers". History of the Spill. Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ↑ Brandon Keim (March 24, 2009). "The Exxon Valdez Spill Is All Around Us". Wired Science. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- 1 2 Graham, Sarah (December 19, 2003). "Environmental Effects of Exxon Valdez Spill Still Being Felt". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 29 March 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Valdez disaster – 15 years of lies". Greenpeace News. Greenpeace. March 24, 2004. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "16 Years After Exxon Valdez Tragedy, Arctic Refuge, America's Coasts Still At Risk" (Press release). Sierra Club. March 23, 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: Fifteen Years Later" (Press release). Defenders of Wildlife. March 24, 2004. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Valdez Photos". NOAA. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2005-07-14.

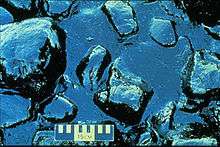

Beginning 3 days after the vessel grounded, a storm pushed large quantities of fresh oil onto the rocky shores of many of the beaches in the Knight Island chain.

- 1 2 Practices that relate to the Exxon Valdez (PDF). Washington, DC: National Transportation and Safety Board. September 18, 1990. pp. 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2010.

- 1 2 "Ten years after but who was to blame?". Greg Palast. March 21, 1999. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ Court Rewards Exxon for Valdez Oil Spill

- ↑ Leveson, Nancy G. (July 2005). "Software System Safety" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 18–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- 1 2 Leveson, p.20

- 1 2 Leveson, p.18

- 1 2 Leveson, p.19

- ↑ Loy, Wesley. "Captain of Exxon Valdez offers 'heartfelt apology' for oil spill." Anchorage Daily News. March 4, 2009. . Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- 1 2 http://www.pwsrcac.org/wp-content/uploads/filebase/programs/environmental_monitoring/report_on_non_mechanical_response.pdf

- ↑ "Governor of Alaska raps Exxon over Valdez oil spill response (1989) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ Ott, Riki (2005). Sound Truth & Corporate Myth$. Dragonfly Sisters Press. p. 561.

- 1 2 Oil Spill Case Histories (PDF). Report No. HMRAD 92-11. NOAA. September 1992. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Use of solvent OK'd in Exxon Valdez oil spill cleanup (Corexit use) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Exxon protests Alaska's rejection of Corexit 9580 dispersant (1990) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- 1 2 http://www.evostc.state.ak.us/static/PDFs/deccleanuptechniques.pdf

- ↑ Oil Spill Facts - Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council

- ↑ Kirby, David (Apr 22, 2013). "Corexit: An Oil Spill Solution Worse Than the Problem?". www.TakePart.com. Participant Media. Retrieved Apr 19, 2016.

- ↑ Baker, Mallen. "Companies in Crisis – What not to do when it all goes wrong". Corporate Social Responsibility News. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ↑ Marybeth Holleman (March 22, 2004). "The Lingering Lessons of the Exxon Valdez Spill". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- 1 2 MacAskill, Ewan (February 2, 2007). "18 years on, Exxon Valdez oil still pours into Alaskan waters". The Guardian. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ↑ SC Jewett; TA Dean; M Hoberg (2001). "Scuba Techniques Used to Assess the Effects of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill". In: SC Jewett (ed). Cold Water Diving for Science. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences, 21st Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Valdez: Ten years on". BBC News. March 18, 1999. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ↑ Williamson, David (December 18, 2003). "Exxon Valdez oil spill effects lasting far longer than expected, scientists say". UNC/News. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Valdez oil spill still a threat: study". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. May 17, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ↑ Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 14 / Friday, January 22, 2010 / Notices

- ↑ 25 years later, scientists still spot traces of oil from Exxon Valdez spill | PBS NewsHour

- 1 2 Exxon Valdez - 25 years after the Alaska oil spill, the court battle continues - Telegraph

- ↑ Lanchester, John (January 7, 2009). "Books: Outsmarted". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ "490 F.3d 1066". law.resource.org. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Staff writer (October 29, 2007). "Supreme Court to review Exxon Valdez award". CNN. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Staff writer (February 27, 2008). "High Court may lower Exxon Valdez damages". CNN. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Savage, David G. (June 26, 2008). "Justices slash Exxon Valdez verdict". articles.latimes.com. Tribune Company. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- 1 2 Exxon v. Baker, 554 U.S. (Supreme Court of the United States of America June 25, 2008).

- ↑ Smith, Sharon. "Exxon's Legal Guardians". CounterPunch. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ "Reaction Of Sen. Leahy On Supreme Court Ruling In Exxon v. Baker". Leahy.senate.gov. June 25, 2008. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ Egelko, Bob (January 28, 2006). "Punitive damages appealed in Valdez spill". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Bandurka, Andrew; Sloane, Simon (March 10, 2005). "Exxon Valdez – D. G. Syndicate 745 vs. Brandywine Reinsurance Company (UK) – Summary of the Court of Appeal Judgment". Holman Fenwick & Willan. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Exxon Corporation 1993 Form 10-K". EDGAR. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. March 11, 1994. Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Erb, George (November 3, 2000). "Exxon Valdez case still twisting through courts". Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Exxon v. Baker, CV-89-00095-HRH (9th Cir. 2006).

- ↑ "News and Information". Exxon Qualified Settlement Fund. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

December 15, 2009 [...] Exxon has now paid to the EQSF all monies owed in the EVOS litigation pursuant to the punitive damages judgment

- ↑ "Exxon Sues Alaska, Charging Cleanup Delay". New York Times. 25 October 1989. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Exxon, Blaming Coast Guard, Says U.S. Is Liable in Alaska Spill". New York Times. 2 October 1990. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Oil Pollution Act of 1990 – Summary". Federal Wildlife and Related Laws Handbook. August 18, 1990. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Carrigan, Alison. "The bill of attainder clause: a new weapon to challenge the Oil Pollution Act of 1990". Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review (Fall 2000). Archived from the original on 29 April 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- 1 2 "Exxon Valdez Is Barred From Alaska Sound". The New York Times. November 2, 2002. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Kizzia, Tom (May 13, 1999). "Double-hull tankers face slow going". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ Loshbaugh, Doug (2000). "School of Hard Knocks". Juneau Empire. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ↑ Carson, Richard; Hanemann, W. Michael (December 18, 1992). "A Preliminary Economic Analysis of Recreational Fishing Losses Related to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill" (PDF). Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "An Assessment of the Impact of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill on the Alaska Tourism Industry" (PDF). Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. August 1990. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Economic Impacts of Spilled Oil". Publications. Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Critics call Valdez cleanup a warning for Gulf workers - CNN.com". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Warning To Gulf Volunteers: Almost Every Cleanup Worker From The 1989 Exxon Valdez Disaster Is Now Dead". Business Insider Australia. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ D. Michael Fry (November 19, 1992). "How Exxon's "Video for Students" Deals in Distortions". The Textbook Letter. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ↑ Thomas, Pierre; Weiser, Benjamin (13 April 1996). "Reputed 'Manifesto' Recovered". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

Further reading

- Lee, Douglas B. (August 1989). "Tragedy in Alaska Waters". National Geographic. Vol. 176 no. 2. pp. 260–263. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

- NTSB safety recommendation to address crew management deficiencies at Exxon and in industry

- Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council

- ExxonMobil updates and news on Valdez

- Images from the Exxon Valdez oil spill from the National Ocean Service Office of Response and Restoration

- EVOS Damage Assessment and Restoration at National Marine Fisheries Service

- Oil Spill Profiles: Exxon Valdez at United States Environmental Protection Agency

- US National Response Team

- Exxon Valdez oil spill at Encyclopedia of Earth

- Ronen Perry, "Economic Loss, Punitive Damages, and the Exxon Valdez Litigation" in Georgia Law Review (2010)

- The story behind the oil spill verdict – originally published in San Diego Union-Tribune

- Alaskan Regional Response Team report on the Exxon Valdez disaster

- BP Played Central Role in Botched Containment of 1989 Exxon Valdez Disaster – video report by Democracy Now!

- The short film Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Assessment (April 24, 1990) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film Exxon Valdez: One Year Later (March 22, 1990) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Photos related to the oil spill from the Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (ARLIS)

- "25 Years After Exxon Valdez, BP Was the Hidden Culprit" at Truthdig (March 23, 2014)