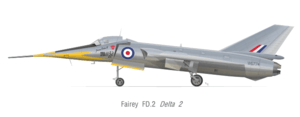

Fairey Delta 2

| Fairey Delta 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

| World speed record holder WG774 | |

| Role | high-speed research aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Fairey Aviation Company |

| First flight | 6 October 1954 |

| Introduction | Experimental |

| Retired | 1966 (WG777), 1973 (WG774) |

| Status | On public display |

| Primary user | Royal Aircraft Establishment |

| Number built | 2 |

|

| |

The Fairey Delta 2 or FD2 (internal designation Type V within Fairey) was a British supersonic research aircraft produced by the Fairey Aviation Company in response to a specification from the Ministry of Supply for investigation into flight and control at transonic and supersonic speeds.

The aircraft was the first to exceed 1000 mph, flying faster than the sun moves across the sky, and held the World Air Speed Record for over a year.

It was modified as the BAC 221 to test the "ogee delta" wing design which was used on the Concorde SST.

Design and development

The Delta 2 was a mid-wing tailless delta monoplane, with an oval cross-section fuselage and the engine air intakes blended into the wing roots. The engine was a Rolls-Royce Avon RA.14R with reheat. The Delta 2 had a very long tapering nose which would normally have obscured forward vision during landing, take-off and movement on the ground. But as an innovation to compensate, the nose section and cockpit drooped 10°, in a similar way to that used later on Concorde. Sir Robert Lickley was in charge of its design and development at Fairey.

The wing had 60° leading edge sweep and was very thin, at only 4% thickness-chord ratio, making it one of the thinnest known at that time. It housed the main undercarriage and fuel tanks.

The Delta was the first British aircraft to fly using all-powered controls. The flight control system was hydraulically operated, having dual systems throughout and no mechanical backup. Fairey had recently developed a new high-pressure hydraulic system and this was used in the design. The hydraulics provided no feedback or "feel" to the pilot's controls, so another system providing artificial feel was necessary.[1]

Two aircraft were built: Serial numbers WG774 and WG777.

The FD2 was used as the basis for Fairey's submissions to the Ministry for advanced all weather interceptor designs leading to the Fairey Delta 3 for the F.155 specification, but it never got past the drawing board stage.

Testing

The first FD2 was aircraft WG774 which made its maiden flight on 6 October 1954, flown by Fairey test pilot Peter Twiss. On 17 November 1954, WG774 suffered engine failure on its 14th flight when internal pressure build-up collapsed the fuselage collector tank, closing off the fuel supply to the engine, while heading away from the airfield at 30,000 ft (9,100 m), 30 mi (50 km) after take-off from Boscombe Down. Twiss managed to glide to a dead-stick landing at high speed on the airfield. Only the nose gear had deployed, and the aircraft sustained damage that sidelined it for eight months. Twiss, who was shaken up by the experience but otherwise uninjured, received the Queen's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air.[2] The test programme did not resume until August 1955.[3] During this period, the aircraft made repeated supersonic test runs over southern Britain, and many claims for damages against the supersonic bangs were received.[1]

Following the record-breaking run (see below), routine testing resumed. Low-level supersonic testing still remained to be carried out. Due to the perceived heightened risk posed by supersonic bangs at low level, the Ministry of Supply refused to allow this testing over the UK, so Fairey took the Delta 2 first to France and later to Norway for these tests. The French government required the tests to be insured against damage claims. This proved impractically expensive with any UK based insurance company, but a French company insured them for £40. No claims were ever received in either France or Norway.[1]

Once the manufacturer's testing was completed, the aircraft were handed over to the Royal Aircraft Establishment.

The record attempt

The test pilot Peter Twiss realised that the Delta 2 was capable of speeds above 1,000 miles per hour and proposed an attempt on the air speed record, then held since 1955 by a North American F-100 Super Sabre. Fairey Aviation found the Ministry of Supply unsupportive, the prevailing belief being that manned military aircraft would soon be replaced by guided missiles. The company had great difficulty in obtaining permission for the attempt. The Ministry loaned Fairey the aircraft but the company had to finance the rest of the bid almost entirely by itself.

In order to reduce the risk of another competitor beating them to it, preparations had to be carried out in a short space of time and in great secrecy. No equipment then existed capable of measuring the flight at such speeds, and the development and deployment of a suitable system became a major technical challenge in itself.

Operational demands on both the pilot and ground crews were severe and many runs were attempted but failed to qualify on one technicality or another. On the final day available, the first run also failed. The second and last run on that day became the only chance left before the attempt would end.

On 10 March 1956 the Fairey Delta 2 broke the World Air Speed Record, raising it to 1,132 mph (1,811 km/h) or Mach 1.73, an increase of some 300 mph (480 km/h) over the previous record, and thus becoming the first aircraft to exceed 1,000 mph (1,600 km/h) in level flight.

At this speed, when flying westward the aircraft flies faster than the apparent motion of the sun, making the sun appear to move backwards in the sky. Peter Twiss became the first man to fly faster than the sun.

The record stood until 12 December 1957 when it was surpassed by a McDonnell JF-101A Voodoo of the United States Air Force.[1][4]

BAC 221

Development of the Concorde was based on a new type of delta wing developed at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) known as the ogee or ogival delta design. This design aimed to improve both supersonic performance through limited span, and low-speed performance through the creation of vortices between the wing and fuselage that increased air velocity over the wing and thereby increased lift. In order to make full use of this effect, the wing should be as long as possible, and highly swept at the root. Continued studies of this basic concept led to the ogee layout.

Low-speed testing of the concept was already being provided by the Handley Page HP.115. Although high-speed performance appeared to be predictable, a dedicated testbed aircraft was desired, especially for drag measurements. As early as 1958, the RAE and Fairey began discussions about converting one of the Delta's to the support the ogee wing. Fairey proposed stretching the fuselage a further three feet to better match the long planform, with the wing extending out onto the drooping nose. However, calculations showed that this extension was not great enough to counter the forward moving centre of pressure (CoP) that resulted from the extended planform, and there were also concerns that the over-wing engine intakes would swallow the vortex above the wing.[5]

Further work was disrupted in 1960 when Fairey was purchased by Westland Aircraft, who handed further development of the conversion to Hunting Aircraft. In July the programme moved to Bristol, now part of the larger British Aircraft Corporation. Bristol suggested two ways forward, a minimal conversion with a sub-optimal wing but no other major changes, or a maximal conversion with a larger six foot extension to the fuselage and a much taller landing gear more typical of the type expected on the Concorde. Both would also be equipped with a new Elliott Brothers stabilization system, and have the engine intakes moved under the wing. A contract for the "maximal" conversion was sent in September, and WG774 was flown to Bristol's Filton plants on the 5th. After a delay, construction began in April 1961 and the newly christened BAC 221 was completed on 7 July.[5]

Several problems were encountered during the conversion. The new lengthened landing gear required more hydraulic fluid, which required a larger reservoir to hold it, pump to move it quickly enough through the system, and so on through the hydraulic system. Retaining the relatively simple intakes but only on the bottom of the wing presented the issue that the airflow into the engine was from below, as opposed to the entire compressor face, so the ducts were extended above the wing to split the airflow evenly. This produced a noticeable bulge on the upper surface of the wing. No attempt was made to fit variable intakes. At high throttle settings there is considerable suction into the inlets, and sudden down-throttle results in air "spilling" out of the intakes, which was a concern because it could flow above the wing and disrupt the vortex. Small lips were added to the intakes to help prevent this, but this proved to cause intake buzzing. Changes to the ducts, helped by Rolls-Royce, addressed this.[5]

One major advantage of the new design was larger fuel capacity, which was a major problem for the original FD.2. The FD had often run out of fuel while still accelerating, thereby never reaching its full performance. The modifications for the 221 meant it was not capable of the same levels of performance, but Mach 1.6 was reached in testing.[5]

In total, it featured a new wing, engine inlet configuration, a Rolls-Royce Avon RA.28, modified vertical stabilizer and a lengthened undercarriage to mimic Concorde's attitude on the ground. It first flew in this form on 1 May 1964.[6] It was used from 1964 until 1973.

Aircraft on display

- WG774, in BAC 221 form, is now on display alongside the British Concorde prototype at the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton.

- WG777, is preserved at the Royal Air Force Museum at RAF Cosford, alongside many other supersonic research aircraft.

Operators

Specifications (Fairey Delta 2)

Data from [7]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 51 ft 7½ in (15.74 m)

- Wingspan: 26 ft 10 in (8.18 m)

- Height: 11 ft 0 in (3.35 m)

- Wing area: 360 ft2 (33.44 m2)

- Empty weight: 11,000 lb (4990 kg)

- Gross weight: 13,884 lb (6298 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Rolls-Royce Avon 200, 10,000 lbf (44.59 kN)

Performance

- Maximum speed: >1300 mph (>2092 km/h)

- Range: 830 miles (1336 km)

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fairey Delta 2. |

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Twiss (2000).

- ↑ Taylor, 1984, pp. 430-431

- ↑ Jackson, Robert, "Combat Aircraft Prototypes since 1945", Arco/Prentice Hall Press, New York, New York, 1986, Library of Congress card number 85-18725, ISBN 0-671-61953-5, page 104.

- ↑ Taylor, 1984, pp. 431-433

- 1 2 3 4 "BAC.211: Slender-delta Research Aircraft", Flight International, 23 July 1964, p. 133-138

- ↑ Taylor 1965, p.130.

- ↑ Orbis 1985, p. 1695

Bibliography

- Taylor, H. A. Fairey Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam, 1974. ISBN 0-370-00065-X.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1965-66. London:Sampsom Low, Marston, 1965.

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982-1985), 1985, Orbis Publishing

- Twiss, Peter. Faster than the Sun. London: Grub Street, Paperback edition, 2000. ISBN 1-902304-43-8.

- Winchester, Jim. Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft. Rochester, Kent, UK: Grange books plc, 2005. ISBN 1-84013-809-2.