Fascia Training

Fascia training describes sports activities and movement exercises that attempt to improve the functional properties of the muscular connective tissues in the human body, such as tendons, ligaments, joint capsules and muscular envelopes. Also called fascia, these tissues take part in a body-wide tensional force transmission network and are responsive to training stimulation.[1]

Origin

Whenever muscles and joints are moved this also exerts mechanical strain on related fascial tissues. The general assumption in sports science had therefore been that muscle strength exercises as well as cardiovascular training would be sufficient for an optimal training of the associate fibrous connective tissues. However, recent ultrasound-based research revealed that the mechanical threshold for a training effect on tendinous tissues tends to be significantly higher than for muscle fibers. This insight happened roughly during the same time in which the field of fascia research attracted major attention by showing that fascial tissues are much more than passive transmitters of muscular tension (years 2007 – 2010). Both influences together triggered an increasing attention in sports science towards the question whether/how fascial tissues can be specifically stimulated with active exercises.[2]

The first print publication addressing this question in more detail was a chapter contribution in the first academic text book on fascia,[3] of which an extended version of this chapter was subsequently published in a scientific journal.[4] In these texts the authors Robert Schleip and Divo Gitta Müller described major training principles as well as practical applications. In collaboration with other sports therapist they later developed this into a specific training method called Fascial Fitness. Significant contributions in this development were made by the author and body therapist Thomas W. Myers (USA), the sports chiropractor Wilbour Kelsick (Canada), as well as the German physical education teachers Markus Rossmann and Stefan Dennenmoser.

Other fascia oriented training approaches that particularly aim at a remodeling of fascial tissues include the MELT Method (Myofascial Energetic Length Technique), Yin Yoga, Fascial Yoga, several forms of Pilates, as well as the self-defense method of Wujifa and similar styles of Martial Arts.

The catapult effect

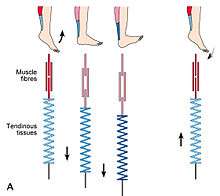

The large jumping power of kangaroos and gazelles stems less from their muscles but rather from their highly elastic tendons. These tissues are able to store and release kinetic energy with a very high efficiency. A similar impressive storage capacity has also been found in human running, hopping and walking.[5]

Using high resolution ultrasound imaging it was shown that during such movements the engaged muscle fibers hardly change their length; in fact they contract rather isometrically. In contrast, the involved tendionous and aponeurotic fibers change their operating length significantly. Fascial training methods attempt to improve this capacity by including movements with a high elastic rebound quality. It was shown that few elastic bounces per week can be sufficient to induce – over a period of several months – a higher elastic performance capacity in the affected related fascial tissues.[6]

Principles

According to a publication by Divo G. Müller and Robert Schleip a fascial training rest on the following principles[3]

- Preparatory counter-movement (increasing elastic recoil by pre-stretching involved fascial tissues);

- The Ninja principle (focus on effortless movement quality);

- Dynamic stretching (alternation of melting static stretches with dynamic stretches that include mini-bounces, with multiple directional variations);

- Proprioceptive refinement (enhancing somatic perceptiveness by mindfulness oriented movement explorations);

- Hydration and renewal (foam rolling and similar tool-assisted myofascial self-treatment applications);

- Sustainability: respecting the slower adaptation speed but more sustaining effects of fascial tissues (compared with muscles) by aiming at visible body improvements of longer time periods, usually said to happen over 3 to 24 months.

Training elements

Usually these four training elements are combined • Elastic rebound • Dynamic stretching • Myofascial self treatment • Proprioceptive refinement

General claims

Fascia training is suggested as a sporadic or regular addition to comprehensive movement training. It promises to lead towards remodeling of the body-wide fascial network in such a way that it works with increased effectiveness and refinement in terms of its kinetic storage capacity as well as a sensory organ for proprioception.[7]

Evidence

While good to moderate scientific evidence exists for several of the included training principles – e.g. the inclusion of elastic recoil as well as a training of proprioceptive refinement – there is currently insufficient evidence for the claimed beneficial effects of a fascia oriented exercises program as such, consisting of a combination of the above described four training elements.[8][9]

References

- ↑ Robert Schleip, "Fascia as a Sensory Organ" in: Erik Dalton, Dynamic Body Exploring Form, Expanding Function. Freedom from Pain Institute, Oklahoma City pp 137–163

- ↑ RL Swanson: Biotensegrity – a unifying theory of biological architecture. American Osteopathic Association 2013, pp. 34-52

- 1 2 Divo G. Müller & Robert Schleip: Fascial Fitness – Suggestions for a fascia oriented training approach in sports and movement therapies. In: R. Schleip, T. W. Findley, L. Chaitow, P. A. Huijing (eds): Fascia – the tensional network of the human body. The science and clinical applications in manual and movement therapy. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh 2009, p. 465-467. ISBN 978-0702034251

- ↑ Schleip, Robert; Müller, Divo Gitta (2013). "Training principles for fascial connective tissues: Scientific foundation and suggested practical applications". Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 17 (1): 103–15. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.06.007.

- ↑ Kram, Rodger; Dawson, Terence J (1998-05-01). "Energetics and biomechanics of locomotion by red kangaroos (Macropus rufus)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B. 120 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1016/s0305-0491(98)00022-4. ISSN 1096-4959. PMID 9787777.

- ↑ Hoffrén-Mikkola, Merja; Ishikawa, Masaki; Rantalainen, Timo; Avela, Janne; Komi, Paavo V. (2015-05-01). "Neuromuscular mechanics and hopping training in elderly". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 115 (5): 863–877. doi:10.1007/s00421-014-3065-9. ISSN 1439-6327. PMID 25479729.

- ↑ Leon Chaitow: Fascial Dysfunction – Manual Therapy Approaches. Handspring Publishing Edinburgh 2014, p. 133

- ↑ "fascia training studies".

- ↑ Schleip R., Baker A.: Fascia in Sport and Movement. Handspring Publishing 2015, ISBN 978-1-909141-07-0