Federalist No. 54

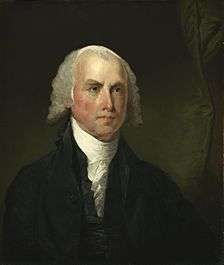

Federalist Paper No. 54 is an essay by James Madison, the fifty-fourth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on February 12, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. This paper discusses the way in which the seats in the United States House of Representatives are apportioned among the states. It is titled, "The Apportionment of Members Among the States." The essay was erroneously attributed to John Jay in Alexander Hamilton's enumeration of the authors of the various Federalist Papers.

The chief concern of the article is the representation of slaves in relation to taxation and representation. This federalist paper states that slaves are property as well as people, therefore requiring some representation. This representation is decided to be every three out of five slaves are to be counted, or 3/5 of the total number of slaves.

They decided to use population as a determinant of votes in the House of Representatives, but the three fifths compromise that had taken place a year earlier before this paper was the event that sparked controversy between states, men, and political parties. James Madison, Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64, has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list.[1]

Background

Prior to the Constitution, the Articles of Confederation stated that the apportionment of taxation was based off the land value in each state, causing states to depreciate the value of their land so they weren’t burdened with the overwhelming amount of taxes that they had to pay. To prevent states from manipulating the numbers, Madison wanted to create a system where both taxes and the number of representatives were based off the population, so that if a state claimed too large of a population to gain more seats in the House of Representatives, they would have to pay higher taxes. While this proposal found support, it led to a major problem: the slave states had large populations of slaves, who were ineligible to vote; if they were counted in the population, the slave states would have more seats in the House.[2]

A national convention was assembled for May 1787, to revise the Articles of Confederation. The problem of how to count slaves was a major issue. Southerners wanted slaves to count fully because it would increase the number of representatives allotted to slave-holding states.[3] On the other hand, northern delegates wanted the slaves not to count at all. As they saw it, slaves were not free citizens, and were considered mere property by their masters. After a long deliberation Madison came to a compromise that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person.

The three fifths clause is perhaps the most misunderstood provision of the U.S. constitution because the clause provides that the representation in Congress will be based on "the whole Number of free Persons" and "the three fifths of all other persons". The other persons were slaves. Despite popular understandings, this provision did not declare that the slave states would get extra representation in congress for their slaves, even though those states treated slaves purely as property. The provision was not directly about race, but about status and allocation of political power. Free African American people were counted exactly the same way as whites. The clause provided a mathematical formula that allowed for the allocation of representatives in Congress that factored in the slave population. No slaves could vote in the country, and the clause did not even provide a voice for slaves. This was about the distribution of political power among the states[4]

Three-Fifths Compromise

The three-fifths compromise was proposed by James Wilson in 1789 in order to gain Southern support for the new framework of government by guaranteeing that the South would be strongly represented in the House of Representatives.[5] Naturally, it was more popular in the South than in the North.[6]

In Article I, Section II, Clause III of the United States Constitution, the Three-Fifths Compromise is stated exactly as followed:

"Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states which may be included in this Union, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons."[7]

Madison's Arguments

In the 54th Federalist Paper: The Apportionment of Members Among the States, author, James Madison, reveals his defenses and arguments behind a portion of the United States Constitution, called the Three Fifths Compromise. Madison created the 54th Federalist Paper in order to influence the American public that the compromise was in fact, a successful solution to the differences between the North and the South regions. In the 54th federalist Paper, Madison suggests that "property needs to be protected by government but there is no provision for doing so and property or wealth should have an advantage in representative government but it doesn't so allow southerners to include property at the three fifths scale for the purposes of representation helps correct these problems and if the property is considered equally for taxation then it is justified" (Tea Party, 2010-2016). Although Madison was a strong supporter of the Constitution, he personally felt conflicted about the concept of slavery, which inevitably, left him feeling obligated to defend the three-fifths rule. Throughout the Apportionment of Members Among the States, Madison eventually recognizes that the lives of the slaves are initially considered property under the law, because of the slaves compelling labor, constant trade, and in the end, their liberty was constrained, much like property. Essentially, Madison argues that the law protects the lives of slaves as property, and as a person because in reality, slaveholders could receive punishment for the harm of others. Madison continues to argue through the content of the 54th Federalist Paper, that by the defense of the Constitution and in support of the Three Fifths Compromise, that slaves should be represented with a mixed characteristics, as both property and person[8]

Publication

Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay, Federalist Paper No. 54 was published on February 12, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project of the Federalist Papers, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius [9] Two others were considered, Govenor Morris and William Duer. Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius, or "Friend of Publius." [10] The Federalist Papers were written in an attempt to get the New York citizens to ratify the United States Constitution in 1787, but the specific issue at hand for No. 54 was the way which the seats in the US House of Representatives would be apportioned among the states.

References

- ↑ Finkleman, P. "Three-Fifths Clause: Why Its Taint Persists". Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ "What was the Three-Fifth Compromise?". constitution.law .com. Retrieved 10/1/16. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ McClarey, Donald (25, July 2012). "Federalist 54 – Madison". Almost Chosen People. Retrieved 10, October 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Finkleman, P. "Three-Fifths Clause: Why Its Taint Persists". Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ "The Three-Fifth Compromise".

- ↑ "The Slavery Compromises".

- ↑ Mount, Steve (16, August 2010). "U.S. Constitution Article 1 Section 2". U.S. Constitution. Retrieved 21, October 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Applestein, Donald. "The three-fifths compromise: Rationalizing the irrational". Constitution Daily. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Ohline, H. "Republicanism and Slavery: Origins of the Three-Fifths Clause in the United States Constitutuon". doi:10.1109/ee.1957.6442747.

- ↑ Ohline, A. "Republicanism and Slavery: Origins of the Three-Fifths Clause in the United States Constitutuon". 76.

Further reading

- Hamilton, Alexander, and James Madison. "The Federalist Papers." Congress.gov | Library of Congress. Congress.gov, n.d. Web. 04 Oct. 2016.

- By Extending the Rule to Both Objects, the States Will Have opposite Interests, Which Will Control and Balance Each Other, and Produce the Requisite Impartiality. "The Avalon Project : Federalist No 54." The Avalon Project : Federalist No 54. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Oct. 2016.

- Hamilton, Alexander, et al. The federalist papers. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Kaminski, John P., and Gaspare J. Saladino, eds. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Volume XVI: Commentaries on the Constitution, Public and Private: Volume 4, 1 February to 31 March 1788. Vol. 4. Wisconsin Historical Society, 1986.

- Southard, Bjørn F. Stillion. "In the Shadow of the Gallows: Race, Crime, and American Civic Identity by Jeannine Marie DeLombard (review)." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 18.4 (2015): 798-801.

- Kincaid, John. "The Federalist and V. Ostrom on concurrent taxation and federalism." Publius: The Journal of Federalism 44.2 (2014): 275-297.

- Condit, Celeste Michelle, and John Louis Lucaites. "The rhetoric of equality and the expatriation of African‐Americans, 1776‐1826." Communication Studies 42.1 (1991): 1-21.

- Baker, Pauline H. "The Myth of Middle Class Moderation: African Lessons for South Africa." Issue: A Journal of Opinion 16.2 (1988): 45-48.

- "Primary Documents in American History." Federalist Papers: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress). N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

- "Milestones: 1776–1783 - Office of the Historian." U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

- Costly, Andrew. "The Federalist Papers." - Constitutional Rights Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

- "Proportional Representation | US House of Representatives ..." N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

- "Chapter 7 Representation: By State or by Population? O." N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

- Martinez, J. Michael, and William D. Richardson. "The Federalist Papers And Legal Interpretation /." South Dakota Law Review 45.2 (2000): 307-333. OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson). Web. 18 Oct. 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |