Federalist No. 75

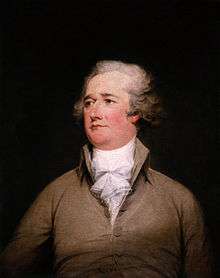

Federalist No. 75 (Federalist Number 75) is an essay by Alexander Hamilton and seventy-fifth in the series of The Federalist Papers. It was published on March 26, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. Its title is, "The Treaty Making Power of the Executive", and it is the seventh in a series of 11 essays discussing the powers and limitations of the Executive branch.

In this paper, Hamilton discusses the reasons for the concurrent power of the Senate and Executive branch to make treaties.

Overview

The topic of Federalist No. 75, written by Alexander Hamilton, is “The Treaty Making Power of the Executive” which clearly discusses why the treaty making power should not be solely entrusted in a single branch of the government. In the opening statements, the main point of the essay is immediately stated which allows the reader of the document to have a short summary of the expected results of the presented arguments. Hamilton proclaims, “The president is to have power, by and with the advice and consent of the senate, to make treaties, provided two-thirds of the senators present concur.”[1] From this statement, the reader can see a foreshadowing of a debate for the power struggle between the executive and legislative branches.

The next topic covered in the document was the proposition of the interest of investing sole power in the President of the United States. Hamilton makes many interesting points, one of which includes his statement, “An avaricious man might be tempted to betray the interests of the state to the acquisition of wealth.”[1] Simply put, a president who is greedy or develops greed might be tempted to use this treaty making power to line his own pockets for a financial gain. Besides the obvious financial benefits possible from gaining this treaty making power, Hamilton argues that it would be utterly irresponsible to let a single person possess this power for a minimum of four years at a time. He states, “However proper or safe it may be in governments where the executive magistrate is an hereditary monarch, to commit to him the entire power of making treaties, it would be utterly unsafe and improper to entrust that power to an elective magistrate of four years' duration.”[1] Although Hamilton makes solid arguments against the executive branch having sole treaty making power, he also forms an equally impressive self-rebuttal from the opposite end of the spectrum. Referring back to his previous statement about entrusting the senate with such an important power, Hamilton writes, “To have entrusted the power of making treaties to the Senate alone would have been to relinquish the benefits of the constitutional agency of the President in the conduct of foreign negotiations.”[1] Hamilton is defending the power, rights, and responsibility of the executive branch. Furthermore, it is vital that the United States has a sole representative to physically travel to or communicate with foreign nations when making treaties. It would be an impossible feat to have the entire senate debate and hash out a treaty with a foreign country, especially if said country was thousands of miles across a vast ocean. He claims, “The essence of the legislative authority is to enact laws or in other words to prescribe rules for the regulation of the society. While the execution of the laws and the employment of the common strength, either for this purpose or for the common defense, seem to comprise all the functions of the executive magistrate.” This sentence basically describes the function of the executive branch which is to enforce laws made by congress and protect the country. Treaties do not fall completely under this category nor do they fall under the jurisdiction of the legislative branch.

Since he does not clearly support one side or the other, he proposes a joint responsibility of power. In the seventy-fifth essay, Hamilton makes his conclusion based on elements such as security, intermixture of powers, and making a small alteration to the existing voting style of the senate. This particular section of the essay is started with Hamilton making a general statement proclaiming, “One ground of objection is the trite topic of the intermixture of powers; some contending that the President ought alone to possess the power of making treaties; others, that it ought to have been exclusively deposited in the Senate.”[1] This is Hamilton’s primary statement in his conclusion which branches out to grab both sides and harmonize them together to create one final solution to the ownership of the power in question. Concerned with the country’s security and principles of anti-corruption, Hamilton states, “It must indeed be clear to a demonstration that the joint possession of the power in question, by the President and the Senate, would afford a greater prospect of security than the separate possession of it by either of them.”[1] Combining both side’s previous arguments, Hamilton suggests that the treaty making power must be shared between both the senate and executive to prevent one side from becoming too powerful and creating a rift in the country’s principle of security. The final opinion shared by Hamilton refers to the alteration of the existing amount of senate members required to pass a proposition. Before the Federalist Papers of September 17, 1787, the law was stated as two-thirds of the total members in which composed the senatorial body had to vote on the proposed issues. Instead, Hamilton suggested, “The only objection which remains to be canvassed, is that which would substitute the proportion of two-thirds of all the members composing the senatorial body, to that of two-thirds of the members present.”[1] Although Federalist No. 75 sheds light on various important topics and seemingly solves many discrepancies in the previous set of laws, not everyone agrees with Hamilton’s point of view.

Under several different pseudonyms, written by various authors, and appearing and various forms, arguments against the ratification of the Federalist Papers were published. Simply named the “Anti-Federalist Papers”, the collection of writings contains the warnings of dangers from tyranny that weaknesses in the proposed Constitution did not adequately provide against, and while some of those weaknesses were corrected by the adoption of the Bill of Rights, others remained.[2] Due to their disorganization and lesser popularity, the Anti-Federalist proved unable to stop the ratification of the US Constitution, which took effect in 1789. Although they proved to be unsuccessful in their mission to prevent the ratification of the new Constitution, they left their mark which can be seen today in the Bill of Rights. The 50 plus contributors of Anti-Federalist were no match for Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay, and their much more structured and well-renowned revisions of the new Constitution. Hamilton especially, contributing to 51 of the 85 articles, was able to produce a much more coherent draft considering his background as an extremely successful lawyer.

The outcome would be a common ground reached between each side; the final statement was declared and submitted to be included in the new United States Constitution. Neither the legislative nor executive branches would receive sole treaty making power, rather they both would work together as a powerhouse to arrive at the best possible outcome with the country’s best interests in mind. The official statement produced by Hamilton being, “The president is to have power, by and with the advice and consent of the senate, to make treaties, provided two-thirds of the senators present concur.”[1] After gathering thoughts, comments, and feedback from the people of the United States, Alexander Hamilton finalized and submitted what eventually became a key piece of the foundation of the United States Constitution.

References

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |