Ford Madox Ford

| Ford Madox Ford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Ford Hermann Hueffer 17 December 1873 Merton, Surrey, England |

| Died |

26 June 1939 (aged 65) Deauville, France |

| Pen name | Ford Madox Hueffer |

| Occupation | Novelist, and publisher |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1892–1939 |

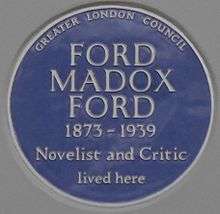

Ford Madox Ford (born Ford Hermann Hueffer (/ˈhɛfər/ HEF-ər);[1] 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals, The English Review and The Transatlantic Review, were instrumental in the development of early 20th-century English literature.

Ford is now remembered for his novels The Good Soldier (1915), the Parade's End tetralogy (1924–28) and The Fifth Queen trilogy (1906–08). The Good Soldier is frequently included among the great literature of the 20th century, including the Modern Library 100 Best Novels,[2] The Observer′s "100 Greatest Novels of All Time",[3] and The Guardian′s "1000 novels everyone must read".[4]

Biography

Ford was born in Wimbledon[5] to Catherine Madox Brown and Francis Hueffer, the eldest of three; his brother was Oliver Madox Hueffer. Ford's father, who became music critic for The Times, was German and his mother English. His paternal grandfather Johann Hermann Hüffer was first to publish Westphalian poet and author Annette von Droste-Hülshoff.

Ford used the name of Ford Madox Hueffer, but in 1919 he changed it to Ford Madox Ford (allegedly after World War I because "Hueffer" sounded too Germanic[6]) in honour of his grandfather, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown, whose biography he had written.

In 1889, after the death of his father, Ford and Oliver went to live with their grandfather in London. Ford graduated from the University College School in London, but never attended university.[7]

In 1894, Ford eloped with his school girlfriend Elsie Martindale. The couple were married in Gloucester and moved to Bonnington. In 1901, the couple moved to Winchelsea.[7] The couple had two daughters, Christina (born 1897) and Katharine (born 1900).[8] Ford's neighbors in Winchelsea included the authors Henry James and H.G. Wells.[7]

In 1904, Ford suffered an agoraphobic breakdown due to financial and marital problems. He went to Germany to spend time with family there and undergo cure treatments.[7]

Between 1918 and 1927 he lived with Stella Bowen, an Australian artist twenty years his junior. In 1920, Ford and Bowen had a daughter, Julia Madox Ford.[9]

In the summer of 1927, the New York Times reported that Maddox had converted a mill building in Avignon, France into a home and workshop that he called "Le Vieux Moulin". The article implied that Ford was reunited with his wife at this point.[10]

Ford spent the last years of his life teaching at Olivet College in Olivet, Michigan. Ford died in Deauville, France, at the age of 65.

Literary life

One of Ford's most famous works is the novel The Good Soldier (1915). Set just before World War I, The Good Soldier chronicles the tragic expatriate lives of two "perfect couples", one British and one American, using intricate flashbacks. In the "Dedicatory Letter to Stella Ford” that prefaces the novel, Ford reports that a friend pronounced The Good Soldier “the finest French novel in the English language!” Ford pronounced himself a "Tory mad about historic continuity" and believed the novelist's function was to serve as the historian of his own time.[11]

Ford was involved in British war propaganda after the beginning of World War I. He worked for the War Propaganda Bureau, managed by C. F. G. Masterman, along with Arnold Bennett, G. K. Chesterton, John Galsworthy, Hilaire Belloc and Gilbert Murray. Ford wrote two propaganda books for Masterman; When Blood is Their Argument: An Analysis of Prussian Culture (1915), with the help of Richard Aldington, and Between St Dennis and St George: A Sketch of Three Civilizations (1915).

After writing the two propaganda books, Ford enlisted at 41 years of age into the Welch Regiment of the British Army on 30 July 1915. He was sent to France. Ford's combat experiences and his previous propaganda activities inspired his tetralogy Parade's End (1924–1928), set in England and on the Western Front before, during and after World War I.

.jpg)

Ford wrote dozens of novels as well as essays, poetry, memoirs and literary criticism. He collaborated with Joseph Conrad on three novels, The Inheritors (1901), Romance (1903) and The Nature of a Crime (1924, although written much earlier). During the three to five years after this direct collaboration, Ford's best known achievement was The Fifth Queen trilogy (1906–1908), historical novels based on the life of Katharine Howard, which Conrad termed, at the time, "the swan song of historical romance."[12] Ford's poem Antwerp (1915) was praised by T.S. Eliot as "the only good poem I have met with on the subject of the war".[13]

Ford's novel Ladies Whose Bright Eyes (1911, extensively revised in 1935)[14] is, in a sense, the reverse of Twain's novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

Promotion of literature

In 1908, Ford founded The English Review. Ford published works with Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, Joseph Conrad, Henry James, May Sinclair, John Galsworthy and William Butler Yeats; and debuted works of Wyndham Lewis, D. H. Lawrence and Norman Douglas. In 1924, he founded The Transatlantic Review, a journal with great influence on modern literature. Staying with the artistic community in the Latin Quarter of Paris, Ford befriended James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound[15] and Jean Rhys, all of whom he would publish (Ford is the model for the character Braddocks in Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises).

As a critic, Ford is known for remarking "Open the book to page ninety-nine and read, and the quality of the whole will be revealed to you." George Seldes, in his book Witness to a Century,[16] describes Ford's recollection of his writing collaboration with Joseph Conrad, and the lack of acknowledgment by publishers of his status as co-author. Seldes recounts Ford's disappointment with Hemingway: "'and he disowns me now that he has become better known than I am.' Tears now came to Ford's eyes." Ford says, "I helped Joseph Conrad, I helped Hemingway. I helped a dozen, a score of writers, and many of them have beaten me. I'm now an old man and I'll die without making a name like Hemingway." Seldes observes, "At this climax Ford began to sob. Then he began to cry."

Hemingway devoted a chapter of his Parisian memoir A Moveable Feast to an encounter with Ford at a café in Paris during the early 1920s. He describes Ford "as upright as an ambulatory, well clothed, up-ended hogshead."

During a later sojourn in the United States, Ford was involved with Allen Tate, Caroline Gordon, Katherine Anne Porter and Robert Lowell (who was then a student).[17] Ford was always a champion of new literature and literary experimentation. In 1929, he published The English Novel: From the Earliest Days to the Death of Joseph Conrad, a brisk and accessible overview of the history of English novels. He had an affair with Jean Rhys, which ended acrimoniously.[18]

Selected works

- The Shifting of the Fire, as H Ford Hueffer, Unwin, 1892.

- The Brown Owl, as H Ford Hueffer, Unwin, 1892.

- The Queen Who Flew: A Fairy Tale, Bliss Sands & Foster, 1894.

- The Cinque Ports, Blackwood, 1900.

- The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story, Joseph Conrad and Ford M. Hueffer, Heinemann, 1901.

- Rossetti, Duckworth, [1902].

- Romance, Joseph Conrad and Ford M. Hueffer, Smith Elder, 1903.

- The Benefactor, Langham, 1905.

- The Soul of London, Alston Rivers, 1905.

- The Heart of the Country, Duckworth, 1906.

- The Fifth Queen (Part One of The Fifth Queen trilogy), Alston Rivers, 1906.

- Privy Seal (Part Two of The Fifth Queen trilogy), Alston Rivers, 1907.

- An English Girl, Methuen, 1907.

- The Fifth Queen Crowned (Part Three of The Fifth Queen trilogy), Nash, 1908.

- Mr Apollo, Methuen, 1908.

- The Half Moon, Nash, 1909.

- A Call, Chatto, 1910.

- The Portrait, Methuen, 1910.

- The Critical Attitude, as Ford Madox Hueffer, Duckworth 1911.

- The Simple Life Limited, as Daniel Chaucer, Lane, 1911.

- Ladies Whose Bright Eyes, Constable, 1911 (extensively revised in 1935).

- The Panel, Constable, 1912.

- The New Humpty Dumpty, as Daniel Chaucer, Lane, 1912.

- Henry James, Secker, 1913.

- Mr Fleight, Latimer, 1913.

- The Young Lovell, Chatto, 1913.

- Antwerp (eight-page poem), The Poetry Bookshop, 1915.

- Henry James, A Critical Study (1915).

- Between St Dennis and St George, Hodder, 1915.

- The Good Soldier, Lane, 1915.

- Zeppelin Nights, with Violet Hunt, Lane, 1915.

- The Marsden Case, Duckworth, 1923.

- Women and Men, Paris, 1923.

- Mr Bosphorous, Duckworth, 1923.

- The Nature of a Crime, with Joseph Conrad, Duckworth, 1924.

- Joseph Conrad, A Personal Remembrance, Little, Brown and Company, 1924.

- Some Do Not . . ., Duckworth, 1924.

- No More Parades, Duckworth, 1925.

- A Man Could Stand Up --, Duckworth, 1926.

- New York is Not America, Duckworth, 1927.

- New York Essays, Rudge, 1927.

- New Poems, Rudge, 1927.

- Last Post, Duckworth, 1928.

- A Little Less Than Gods, Duckworth, [1928].

- No Enemy, Macaulay, 1929.

- The English Novel: From the Earliest Days to the Death of Joseph Conrad (One Hour Series), Lippincott, 1929.

- The English Novel, Constable, 1930.

- Return to Yesterday, Liveright, 1932.

- When the Wicked Man, Cape, 1932.

- The Rash Act, Cape, 1933.

- It Was the Nightingale, Lippincott, 1933.

- Henry for Hugh, Lippincott, 1934.

- Provence, Unwin, 1935.

- Ladies Whose Bright Eyes (revised version), 1935

- Portraits from Life: Memories and Criticism of Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Hardy, H.G.Wells, Stephen Crane, D.H.Lawrence, John Galsworthy, Ivan Turgenev, W.H. Hudson, Theodore Dreiser, A.C. Swinburne, Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, 1937

- Great Trade Route, OUP, 1937.

- Vive Le Roy, Unwin, 1937.

- The March of Literature, Dial, 1938.

- Selected Poems, Randall, 1971.

- Your Mirror to My Times, Holt, 1971.

References

- ↑ Daniel Jones, Everyman's English Pronouncing Dictionary, 13th ed. (rev. A.C. Gimson; London: Dent, 1967), p. 236.

- ↑ Modern Library, "100 Best Novels", 20 July 1998

- ↑ LibraryThing, "Book awards: The Observer's 100 Greatest Novels of All Time"

- ↑ The Guardian, "1000 novels everyone must read", guardian.co.uk, Friday 23 January 2009

- ↑ "Complete Works of Ford Madox Ford, with picture of birthplace in Kingston Road, Wimbledon.". ,. Retrieved 3 Feb 2014.

- ↑ Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast.

- 1 2 3 4 Saunders, Max. "Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939): Biography". The Ford Maddox Society. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑ "Ford Madox Ford Society Biography".

- ↑ The Saddest Story. A Mizener. 1971.

- ↑ BIRKHEAD, MAY (August 14, 1927). "AMERICANS IN PARIS FIND BOOK MATERIAL; Burton Holmes Obtains Unique Pictures -- Maddox Ford Writes in an Old Mill. DEAUVILLE SEASON STARTS Fine Weather Draws Notables to Coast Resort for the Racing and Polo". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Judd, Alan (1991). Ford Madox Ford. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 157.

- ↑ Lewis, Pericles. "Antwerp".

- ↑ Richard A. Cassell, "The Two Sorrells of Ford Madox Ford", in Modern Philology, Vol. 59, No. 2, November 1961, pp. 114–121

- ↑ Lindberg-Seyersted B., Pound/Ford, the story of a literary friendship: the correspondence between Ezra Pound and Ford Madox Ford and their writings about each other, edited by Brita Lindberg-Seyersted, New Directions Publishing, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8112-0833-8

- ↑ Seldes, George (1987), Witness to a Century, Ballantine Books, pp.258-259. ISBN 0-345-35329-3

- ↑ Honaker, Lisa (Summer 1990). "Caroline Gordon: A Biography, and: Flannery O'Connor and the Mystery of Love (review)". MFS: Modern Fiction Studies. 36 (2): 240–42.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Jean Rhys". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

Further reading

- Attridge, John, "Steadily and Whole: Ford Madox Ford and Modernist Sociology," in Modernism/modernity 15:2 ( April 2008), 297–315.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1987). Geniuses Together: American Writers in Paris in the 1920s. Unwin Hyman. ISBN 0-04-440331-3. Contains a sharp, critical biographical sketch of Ford.

- Hawkes, Rob, Ford Madox Ford and the Misfit Moderns: Edwardian Fiction and the First World War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. ISBN 978-0230301535

- Judd, Alan, Ford Madox Ford. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Saunders, Max, Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, 2 vols. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-211789-0 and ISBN 0-19-212608-3

- Thirlwell, Angela, Into the Frame: The Four Loves of Ford Madox Brown. London, Chatto & Windus, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7011-7902-1

- Davison-Pégon, Claire; Lemarchal, Dominique (2011). Ford Madox Ford, France and Provence. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 9789401200462. OCLC 734015160.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ford Madox Ford |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Ford Madox Ford |

- Ford Madox Ford Society

- Petri Liukkonen. "Ford Madox Ford". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Literary Encyclopedia entry on Ford

- Works by Ford Madox Ford at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ford Madox Ford at Internet Archive

- Works by Ford Madox Ford at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Good Soldier complete

- LitWeb.net: Ford Madox Ford Biography

- International Ford Madox Ford Studies

- The Ford Madox Ford Papers at Washington University in St. Louis