H. G. Wells

| H. G. Wells | |

|---|---|

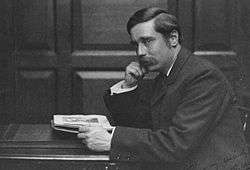

Photograph by George Charles Beresford, 1920 | |

| Born |

Herbert George Wells 21 September 1866 Bromley, Kent, United Kingdom |

| Died |

13 August 1946 (aged 79) Regent's Park, London, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Novelist, teacher, historian, journalist |

| Alma mater | Royal College of Science (Imperial College London) |

| Genre | Science fiction (notably social science fiction), social realism |

| Subject | World history, progress |

| Notable works | |

| Years active | 1895–1946 |

| Spouse |

Isabel Mary Wells (1891–1894, divorced) Amy Catherine Robbins (1895–1927, her death) |

| Children |

George Phillip "G. P." Wells (1901–1985) Frank Richard Wells (1903–1982) Anna-Jane Kennard (1909–2010[1][2]) Anthony West (1914–1987) |

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946)—known as H. G. Wells[3][4]—was a prolific English writer in many genres, including the novel, history, politics, social commentary, and textbooks and rules for war games. Wells is now best remembered for his science fiction novels and is called a "father of science fiction", along with Jules Verne and Hugo Gernsback.[5][6][lower-alpha 1] His most notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.[7]

Wells's earliest specialised training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a specifically and fundamentally Darwinian context.[8] He was also from an early date an outspoken socialist, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathising with pacifist views. His later works became increasingly political and didactic, and he wrote little science fiction, while he sometimes indicated on official documents that his profession was that of journalist.[9] Novels like Kipps and The History of Mr Polly, which describe lower-middle-class life, led to the suggestion, when they were published, that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens,[10] but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in Tono-Bungay (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. A diabetic, in 1934 Wells co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (known today as Diabetes UK).

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 46 High Street, Bromley, in Kent,[11] on 21 September 1866.[4] Called "Bertie" in the family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells (a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricketer) and his wife, Sarah Neal (a former domestic servant). An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper: the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.[12] Payment for skilled bowlers and batsmen came from voluntary donations afterwards, or from small payments from the clubs where matches were played.

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg.[4] To pass the time he started reading books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849 following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, fractured his thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at the Southsea Drapery Emporium, Hyde's.[13] His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices,[11] later inspired his novels The Wheels of Chance and Kipps,[14] which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother being a Protestant and his father a freethinker. When his mother returned to work as a lady's maid (at Uppark, a country house in Sussex), one of the conditions of work was that she would not be permitted to have living space for her husband and children. Thereafter, she and Joseph lived separate lives, though they never divorced and remained faithful to each other. As a consequence, Herbert's personal troubles increased as he subsequently failed as a draper and also, later, as a chemist's assistant. Fortunately for Herbert, Uppark had a magnificent library in which he immersed himself, reading many classic works, including Plato's Republic, and More's Utopia. This would be the beginning of Herbert George Wells's venture into literature.

Teacher

In October 1879 Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children.[13] In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst, and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883 Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his previous, short stay had been remembered.[12][13]

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune at securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest.[12] The following year, Wells won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science in South Kensington, now part of Imperial College London) in London, studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley. As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909. Wells studied in his new school until 1887 with a weekly allowance of 21 shillings (a guinea) thanks to his scholarship. This ought to have been a comfortable sum of money (at the time many working class families had "round about a pound a week" as their entire household income)[15] yet in his Experiment in Autobiography, Wells speaks of constantly being hungry, and indeed, photographs of him at the time show a youth who is very thin and malnourished.

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of The Science School Journal, a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel The Time Machine was published in the journal under the title The Chronic Argonauts. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.

During 1888 Wells stayed in Stoke-on-Trent, living in Basford, and also at the Leopard Hotel in Burslem. The unique environment of The Potteries was certainly an inspiration. He wrote in a letter to a friend from the area that "the district made an immense impression on me." The inspiration for some of his descriptions in The War of the Worlds is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies. His stay in The Potteries also resulted in the macabre short story "The Cone" (1895, contemporaneous with his famous The Time Machine), set in the north of the city.

After teaching for some time, Wells found it necessary to supplement his knowledge relating to educational principles and methodology and entered the College of Preceptors (College of Teachers). He later received his Licentiate and Fellowship FCP diplomas from the College. It was not until 1890 that Wells earned a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology from the University of London External Programme. In 1889–90 he managed to find a post as a teacher at Henley House School, where he taught A. A. Milne.[16][17] His first published work was a Text-book of Biology in two volumes - 1893.

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's residence, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel. He would later go on to court her.

Personal life

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells. The couple agreed to separate in 1894 when he fell in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (later known as Jane), whom he married in 1895.[19] Poor health took him to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where in 1901 he constructed a large family home: Spade House. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip") in 1901 (died 1985) and Frank Richard in 1903 (died 1982).

With his wife Jane's consent, Wells had affairs with a number of women, including the American birth control activist Margaret Sanger, adventurer and writer Odette Keun, Soviet spy Moura Budberg and novelist Elizabeth von Arnim.[20] In 1909 he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves,[21] whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society; and in 1914 a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist Rebecca West, 26 years his junior.[22] In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply".[23] David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011) - a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note) - gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas".[24] These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006 a book was published on the subject.[25]

Writer

Some of his early novels, called "scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including Kipps and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, Tono-Bungay. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind" (1904).[26]

According to James Gunn, one of Wells' major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his "new system of ideas".[27] In his opinion the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader knew certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could really happen, today referred to as "the plausible impossible" and "suspension of disbelief". While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts which the readers were not familiar with. In "Wells's Law", a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Being aware the notion of magic as something real had disappeared from society, he therefore used scientific ideas and theories as a substitute for magic to justify the impossible. Wells's best-known statement of the "law" appears in his introduction to The Scientific Romances of H.G. Wells (1933),

"As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention."[28]

Though Tono-Bungay is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in The World Set Free (1914). This book contains what is surely his biggest prophetic "hit". Scientists of the day were well aware that the natural decay of radium releases energy at a slow rate over thousands of years. The rate of release is too slow to have practical utility, but the total amount released is huge. Wells's novel revolves around an (unspecified) invention that accelerates the process of radioactive decay, producing bombs that explode with no more than the force of ordinary high explosives—but which "continue to explode" for days on end. "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century", he wrote, "than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible ... [but] they did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands". In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction Leó Szilárd read The World Set Free, a book which he said made a great impression on him.[29]

Wells also wrote nonfiction. Wells's first nonfiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled, "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").[30][31]

His bestselling two-volume work, The Outline of History (1920), began a new era of popularised world history. It received a mixed critical response from professional historians.[32] However, it was very popular amongst the general population and made Wells a rich man. Many other authors followed with "Outlines" of their own in other subjects. Wells reprised his Outline in 1922 with a much shorter popular work, A Short History of the World,[33] and two long efforts, The Science of Life (1930) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931). The "Outlines" became sufficiently common for James Thurber to parody the trend in his humorous essay, "An Outline of Scientists"—indeed, Wells's Outline of History remains in print with a new 2005 edition, while A Short History of the World has been re-edited (2006).

From quite early in his career, he sought a better way to organise society, and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was A Modern Utopia (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all";[34] two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, Things to Come). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939). Men Like Gods (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the critic Malcolm Cowley stated "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".[35]

Wells contemplates the ideas of nature and nurture and questions humanity in books such as The Island of Doctor Moreau. Not all his scientific romances ended in a Utopia, and Wells also wrote a dystopian novel, When the Sleeper Wakes (1899, rewritten as The Sleeper Awakes, 1910), which pictures a future society where the classes have become more and more separated, leading to a revolt of the masses against the rulers. The Island of Doctor Moreau is even darker. The narrator, having been trapped on an island of animals vivisected (unsuccessfully) into human beings, eventually returns to England; like Gulliver on his return from the Houyhnhnms, he finds himself unable to shake off the perceptions of his fellow humans as barely civilised beasts, slowly reverting to their animal natures.

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion's diaries, The Journal of a Disappointed Man, published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the Journal; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries, but the rumours persisted until Barbellion's death later that year.

In 1927 a Canadian citizen, Florence Deeks (1864–1959), unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of The Outline of History had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript,[36] The Web of the World's Romance, which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada.[37]

In 2000, A. B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University and a leading Canadian historian, produced a book on the Deeks versus Wells case, called The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past.[38] McKillop had been researching another Canadian historical figure when he came across information relating to this, and intrigued, followed through with this book. According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author; McKillop paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case, and suggests that in a more modern court, she would have been successful.

Deeks's manuscript was apparently sent to MacMillan and Company, UK, to check that references to other works did not violate copyright. It appeared to go through the hands of one of the editors in the UK who passed it onto Wells, as he knew Wells was thinking of a similar project. The net result was that Deeks's eventually rejected work came back and when it was eventually opened, it was found "soiled, thumbed, worn and torn, with over a dozen pages turned down at the corners, and many others creased as if having been bent back in use".[39] When she compared her work to The Outline of History in the winter of 1920–21 she found remarkable similarities, exact text similarities, and the same errors and omissions that marred her work, also in Wells's.

In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, had published in Queen's Law Journal an article on Deeks v. Wells. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book (described as "a novel" in the editorial introduction). While having some sympathy for Deeks, he "challenges the outpouring of public support" for her. He argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she did receive a fair trial. He goes on to say that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004)[40]

In 1933 Wells predicted in The Shape of Things to Come that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940,[41] a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II.[42]

In 1936, before the Royal Institution, Wells called for the compilation of a constantly growing and changing World Encyclopaedia, to be reviewed by outstanding authorities and made accessible to every human being. In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, World Brain, including the essay, "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication.[43] By 1933 he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and bookstores.[43] Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller be prevented from speaking.[43] Near the end of the World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book".[44]

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells also wrote Floor Games (1911) followed by Little Wars (1913). Little Wars is recognised today as the first recreational war game and Wells is regarded by gamers and hobbyists as "the Father of Miniature War Gaming".[45]

Final years

Wells's literary reputation declined as he spent his later years promoting causes that were rejected by most of his contemporaries as well as by younger authors whom he had previously influenced. In this connection George Orwell described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world".[46] G. K. Chesterton quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".[47]

Wells had diabetes,[48] and was a co-founder in 1934 of The Diabetic Association (what is now Diabetes UK, the leading charity for people with diabetes in the UK).[49]

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station KTSA in San Antonio, Texas, Wells took part in a radio interview with Orson Welles, who two years previously had performed a famous radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. During the interview, by Charles C Shaw, a KTSA radio host, Wells admitted his surprise at the widespread panic that resulted from the broadcast, but acknowledged his debt to Welles for increasing sales of one of his "more obscure" titles.[50]

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, Regent's Park, London.[51][52] Some reports also say he died of a heart attack at the flat of a friend in London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You damned fools".[53] He was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946, with his ashes scattered at sea near Old Harry Rocks.[54] A commemorative blue plaque in his honour was installed at his home in Regent's Park.

Political views

The Fabian Society

Wells called his political views socialist. He was for a time a member of the socialist Fabian Society, but broke with them as his creative political imagination, matching the originality shown in his fiction, outran theirs.[55] He later grew staunchly critical of them as having a poor understanding of economics and educational reform. He ran as a Labour Party candidate for London University in the 1922 and 1923 general elections after the death of his friend W. H. R. Rivers, but at that point his faith in the party was weak or uncertain.

Class

Social class was a theme in Wells's The Time Machine in which the Time Traveller speaks of the future world, with its two races, as having evolved from:

"the gradual widening of the present (19th century) merely temporary and social difference between the Capitalist and the Labourer. ... Even now, does not an East-end worker live in such artificial conditions as practically to be cut off from the natural surface of the earth? Again, the exclusive tendency of richer people ... is already leading to the closing, in their interest, of considerable portions of the surface of the land. About London, for instance, perhaps half the prettier country is shut in against intrusion."[56]

Wells has this very same Time Traveller, reflecting his own socialist leanings, refer in a tongue-in-cheek manner to an imagined world of stark class division as "perfect" and with no social problem unsolved. His Time Traveller thus highlights how strict class division leads to the eventual downfall of the human race:

"Once, life and property must have reached almost absolute safety. The rich had been assured of his wealth and comfort, the toiler assured of his life and work. No doubt in that perfect world there had been no unemployed problem, no social question left unsolved."[56]

In his book The Way the World is Going, Wells called for a non-Marxist form of socialism that would avoid both class war and conflict between nations.[57]

Democracy

Fred Siegel of the center-right Manhattan Institute wrote of Wells's unflattering take on American democracy: “Wells was appalled by the decentralised nature of America’s locally oriented party and country-courthouse politics. He was aghast at the flamboyantly corrupt political machines of the big cities, unchecked by a gentry that might uphold civilised standards. He thought American democracy went too far in providing leeway to the poltroons who ran the political machines and the ‘fools’ who supported them.”[58] Siegel goes on to note Wells’s dislike of America’s not allowing African Americans to vote.[58]

World government

Wells's most consistent political ideal was the World State. He stated in his autobiography that from 1900 onward he considered a World State inevitable. He envisioned the state to be a planned society that would advance science, end nationalism, and allow people to progress by merit rather than birth. Wells's 1928 book The Open Conspiracy argued that groups of campaigners should advocate a "world commonwealth", governed by a scientific elite, that would work to eliminate problems such as poverty and warfare.[59] In 1932, Wells told Young Liberals at the University of Oxford that progressive leaders must become liberal fascists who would "compete in their enthusiasm and self-sacrifice" against the advocates of dictatorship.[60][61] In 1940, Wells published a book called The New World Order that outlined his plan as to how a World Government would be set up. In The New World Order, Wells admitted that the establishment of such a government could take a long time, and be created in a piecemeal fashion.[62]

Eugenics

Some of Wells's early science fiction works reflect his thoughts about the degeneration of humanity.[63] Wells doubted whether human knowledge had advanced sufficiently for eugenics to be successful. In 1904 he discussed a survey paper by Francis Galton, co-founder of eugenics, saying, "I believe that now and always the conscious selection of the best for reproduction will be impossible; that to propose it is to display a fundamental misunderstanding of what individuality implies ... It is in the sterilisation of failure, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies". In his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For? Wells included among the human rights he believed should be available to all people, "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment".[64]

Race

Wells's 1906 book The Future in America, contains a chapter, "The Tragedy of Colour", which discusses the problems facing black Americans.[65] While writing the book, Wells met with Booker T. Washington, who provided him with much of his information for the book.[66] Wells praised the "heroic" resolve of black Americans, stating he doubted if the US could:

"show any thing finer than the quality of the resolve, the steadfast effort hundreds of black and coloured men are making to-day to live blamelessly, honourably, and patiently, getting for themselves what scraps of refinement, learning, and beauty they may, keeping their hold on a civilization they are grudged and denied."[65]

In his 1916 book What Is Coming? Wells states, "I hate and despise a shrewish suspicion of foreigners and foreign ways; a man who can look me in the face, laugh with me, speak truth and deal fairly, is my brother, though his skin is as black as ink or as yellow as an evening primrose".[67]

In The Outline of History, Wells argued against the idea of "racial purity", stating: "Mankind from the point of view of a biologist is an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture. ... [A]ll races are more or less mixed".[68]

In 1931 Wells was one of several signatories to a letter in Britain (along with 33 British MPs) protesting against the death sentence passed upon the African-American Scottsboro Boys.[69]

In 1943 Wells wrote an article for the Evening Standard, "What a Zulu Thinks of the English", prompted by receiving a letter from a Zulu soldier, Lance Corporal Aaron Hlope.[70] Wells's article was a strong attack on anti-black discrimination in South Africa. Wells claimed he had "the utmost contempt and indignation for the unfairness of the handicaps put upon men of colour". Wells also denounced the South African government as a "petty white tyranny".[70]

Zionism

Regarding the Jewish people, Wells was relatively cosmopolitan: “There is something very ugly about many Jewish faces, but there are gentile faces just as coarse and gross.”[71] Wells had given some moderate, unenthusiastic support for Territorialism before the First World War, but later became a bitter opponent of the Zionist movement in general. He saw Zionism as an exclusive and separatist movement which challenged the collective solidarity he advocated in his vision of a world state. The Jews themselves were responsible for anti-Semitism due to their ancient irrational ritual, self-exclusion and the concept of the Chosen people:

"Today… these implacable nationalists are still conspicuously seeking suitable regions … where, pursuing an ancient and irrational ritual so far as it suits them, they can sustain a solidarity foreign and uncongenial to all the people about them… No country wants them on such conditions. Why should any country want these inassimilable aliens bent on preserving their distinctness?"[72]

The Chosen people idea took a “form of a persistent organised attitude of self-exclusion from the common fellowship of the world … Everywhere the same reaction occurs and everywhere the Jew expresses his astonishment. Not only Christians but Turks have resorted to pogroms.”[73] No other result could be from the Chosen people idea associating with Nazism:

"[I]t is essentially a bad tradition, and the fact that for two thousand years the Jews on the whole have been roughly treated by the rest of mankind does not make it any less bad … people are apt to catch up and repeat phrases about the nobility in the Book of Isaiah on the strength of a few chance quotations torn from their context. But let the reader take that book and read for himself straightforwardly, and note the setting of theses fragments. Much of it is ferocious; extraordinarily like the rantings of some Nazi propagandist.”[74]

No supporter of Jewish identity in general, Wells had in his utopian writings predicted the ultimate assimilation of the Jewish people.[75] In notes to accompany his biographical novel A Man of Parts David Lodge describes how Wells came to regret his attitudes to the Jews as he became more aware of the extent of the Nazi atrocities.[76] This included a letter of apology written to Chaim Weizmann for earlier statements he had made.[76]

First World War

He supported Britain in the First World War in his 1914 article, "Why Britain Went To War",[77] despite his many criticisms of British policy, and opposed, in 1916, moves for an early peace.[78] In an essay published that year he acknowledged that he could not understand those British pacifists who were reconciled to "handing over great blocks of the black and coloured races to the [German Empire] to exploit and experiment upon" and that the extent of his own pacifism depended in the first instance upon an armed peace, with "England keep[ing] to England and Germany to Germany". State boundaries would be established according to natural ethnic affinities, rather than by planners in distant imperial capitals, and overseen by his envisaged world alliance of states.[79]

Japan

Wells described his impression of Shintoism: “To the Western mind accustomed to a widely different system of myths and absurdities, this reads like monstrous nonsense. But it is wiser not to say that in Japan.”[80] He emphasised the brutality of the Japanese tradition. Forty-seven Ronin, for example, “is the heroic consummation of a vendetta, ending, after the decapitation of the initiator of the feud, with the hara-kiri of these forty-seven heroes.”[81] Having such traditions, the Japanese should not complain about the “aggressive” external world from which Japan was no longer ringed-in: “Perry’s guns in 1853 aroused that ringed-in Japan of blood feuds, hara-kiri, and heroic decapitations to the existence of a dangerous and aggressive outer world.”[82]

Soviet Union

The leadership of Joseph Stalin led to a change in his view of the Soviet Union even though his initial impression of Stalin himself was mixed. He disliked what he saw as a narrow orthodoxy and intransigence in Stalin. He did give him some praise saying in an article in the left-leaning New Statesman magazine in 1934, "I have never met a man more fair, candid, and honest" and making it clear that he felt the "sinister" image of Stalin was unfair or false.[83] Nevertheless, he judged Stalin's rule to be far too rigid, restrictive of independent thought, and blinkered to lead toward the Cosmopolis he hoped for.[84] In the course of his visit to the Soviet Union in 1934, he debated the merits of reformist socialism over Marxism-Leninism with Stalin.[85]

In 1939 Wells denounced the ideological takeover of science by fascism and communism:

"In Communist circles you may hear the most terrible balderdash about proletarian chemistry or proletarian mathematics. In Germany also it is alleged that some remarkable iniquity attaches to Jewish physics and Einstein is denounced and banned."[86]

Other endeavours

Wells brought his interest in art and design, and politics together when he and other notables signed a memorandum to the Permanent Secretaries of the Board of Trade, among others. The November 1914 memorandum expressed the signatories concerns about British industrial design in the face of foreign competition. The suggestions were accepted, leading to the foundation of the Design and Industries Association.[87] In the 1920s he was an enthusiastic supporter of rejuvenation attempts by Eugen Steinach and others. He was a patient of Dr Norman Haire (perhaps a rejuvenated one) and in response to Haire's 1924 book Rejuvenation: the Work of Steinach, Voronoff, and Others,[88] Wells prophesied a more mature, graver society with "active and hopeful children" and adults "full of years" where none will be "aged".[89]

In his later political writing, Wells incorporated into his discussions of the World State a notion of universal human rights that would protect and guarantee the freedom of the individual. His 1940 publication The Rights of Man laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[90]

Summary

In the end Wells's contemporary political impact was limited, excluding his fiction's positivist stance on the leaps that could be made by physics towards world peace. His efforts regarding the League of Nations, on which he collaborated on the project with Leonard Woolf with the booklets The Idea of a League of Nations, Prolegomena to the Study of World Organization, and The Way of the League of Nations, became a disappointment as the organization turned out to be a weak one unable to prevent the Second World War, which itself occurred towards the very end of his life and only increased the pessimistic side of his nature.[91] In his last book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945) he considered the idea that humanity being replaced by another species might not be a bad idea. He also came to refer to the Second World War era as "The Age of Frustration".

Religious views

Wells wrote in his book God the Invisible King (1917) that his idea of God did not draw upon the traditional religions of the world:

"This book sets out as forcibly and exactly as possible the religious belief of the writer. [Which] is a profound belief in a personal and intimate God. ... Putting the leading idea of this book very roughly, these two antagonistic typical conceptions of God may be best contrasted by speaking of one of them as God-as-Nature or the Creator, and of the other as God-as-Christ or the Redeemer. One is the great Outward God; the other is the Inmost God. The first idea was perhaps developed most highly and completely in the God of Spinoza. It is a conception of God tending to pantheism, to an idea of a comprehensive God as ruling with justice rather than affection, to a conception of aloofness and awestriking worshipfulness. The second idea, which is opposed to this idea of an absolute God, is the God of the human heart. The writer would suggest that the great outline of the theological struggles of that phase of civilisation and world unity which produced Christianity, was a persistent but unsuccessful attempt to get these two different ideas of God into one focus."[92]

Later in the work he aligns himself with a "renascent or modern religion ... neither atheist nor Buddhist nor Mohammedan nor Christian ... [that] he has found growing up in himself".[93]

Of Christianity he said: "it is not now true for me. ... Every believing Christian is, I am sure, my spiritual brother ... but if systemically I called myself a Christian I feel that to most men I should imply too much and so tell a lie". Of other world religions he writes: "All these religions are true for me as Canterbury Cathedral is a true thing and as a Swiss chalet is a true thing. There they are, and they have served a purpose, they have worked. Only they are not true for me to live in them. ... They do not work for me".[94] In The Fate of Homo Sapiens, published in 1939, Wells criticised almost all world religions and philosophies, stating "there is no creed, no way of living left in the world at all, that really meets the needs of the time… When we come to look at them coolly and dispassionately, all the main religions, patriotic, moral and customary systems in which human beings are sheltering today, appear to be in a state of jostling and mutually destructive movement, like the houses and palaces and other buildings of some vast, sprawling city overtaken by a landslide.[95]

Literary influence

The science fiction historian John Clute describes Wells as "the most important writer the genre has yet seen", and notes his work has been central to both British and American science fiction.[96] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921, 1932, 1935, and 1946.[7]

In Britain, Wells's work was a key model for the British "Scientific Romance", and other writers in that mode, such as Olaf Stapledon,[97] J. D. Beresford,[98] S. Fowler Wright,[99] and Naomi Mitchison,[100] all drew on Wells's example. Wells was also an important influence on British science fiction of the period after the Second World War, with Arthur C. Clarke[101] and Brian Aldiss[102] expressing strong admiration for Wells's work.

In the United States, Hugo Gernsback reprinted most of Wells's work in the pulp magazine Amazing Stories, regarding Wells's work as "texts of central importance to the self-conscious new genre".[96] Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury,[103] Isaac Asimov,[104] Frank Herbert[105] and Ursula K. Le Guin[106] all recalled being influenced by Wells's work.

Wells also inspired writers of European speculative fiction such as Karel Čapek[106] and Yevgeny Zamyatin.[106]

Representations

Literary

- The superhuman protagonist of J. D. Beresford's 1911 novel, The Hampdenshire Wonder, Victor Stott, was based on Wells.[98]

- In M. P. Shiel's short story "The Primate of the Rose" (1928), there is an unpleasant womaniser named E. P. Crooks, who was written as a parody of Wells.[107] Wells had attacked Shiel's Prince Zaleski when it was published in 1895, and this was Shiel's response.[107] Wells would later praise Shiel's The Purple Cloud (1901); in turn Shiel expressed admiration for Wells, referring to him at a speech to the Horsham Rotary Club in 1933 as "my friend Mr. Wells".[107]

- In C. S. Lewis' novel That Hideous Strength (1945), the character Jules is a caricature of Wells,[108] and much of Lewis's science fiction was written both under the influence of Wells and as an antithesis to his work (or, as he put it, an "exorcism"[109] of the influence it had on him).

- In Saul Bellow's novel Mr. Sammler's Planet (1970), Wells is one of several historical figures the protagonist met when he was a young man.[110]

- In Brian Aldiss' novella The Saliva Tree, Wells has a small off screen guest role.[111]

- Wells is one of the two George's in Paul Levinson's 2013 time-travel novelette, "Ian, George, and George," published in Analog Magazine.[112]

Dramatic

- Rod Taylor portrays Wells[113][114] in the 1960 science fiction film The Time Machine (based on the novel of the same name), in which Wells uses his time machine to try and find his Utopian society.[114]

- Malcolm MacDowell portrays Wells in the 1979 science fiction film Time After Time, in which Wells uses a time machine to pursue Jack the Ripper to the present day.[114] In the film, Wells meets "Amy" in the future who then returns to 1895 to become his second wife Amy Catherine Robbins.

- Wells is portrayed in the 1985 story Timelash from the 22nd season of the BBC science-fiction television series Doctor Who. In this story, Herbert, an enthusiastic temporary companion to the Doctor, is revealed to be a young H. G. Wells. The plot is loosely based upon the themes and characters of The Time Machine with references to The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man and The Island of Doctor Moreau. The story jokingly suggests that Wells's inspiration for his later novels came from his adventure with the Sixth Doctor.

- In the BBC2 anthology series Encounters about imagined meetings between historical figures, Beautiful Lies, by Paul Pender (15 August 1992) centred on an acrimonious dinner party attended by Wells (Richard Todd), George Orwell (Jon Finch), and William Empson (Patrick Ryecart).

- The character of Wells also appeared in several episodes of Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1993–1997), usually pitted against the time-traveling villain known as Tempus (Lane Davies). Wells's younger self was played by Terry Kiser, and the older Wells was played by Hamilton Camp.

- In the British TV mini-series The Infinite Worlds of H.G. Wells (2001), several of Wells's short stories are dramatised, but are adapted using Wells himself (Tom Ward) as the main protagonist in each story.

- In the Disney Channel Original Series Phil of the Future, which centers around time-travel, the present-day high school that the main characters attend is named "H.G. Wells"

- In the 2006 television docudrama HG Wells: War with the World, Wells is played by Michael Sheen.

- On the science fiction television series Warehouse 13 (2009–2014), there is a female version Helena G. Wells. When she appeared she explained that her brother was her front for her writing because a female science fiction author would not be accepted.

- Comedian Paul F. Tompkins portrays a fictional Wells as the host of The Dead Authors Podcast, wherein Wells uses his time machine to bring dead authors (played by other comedians) to the present and interview them.

- H.G. Wells as a young boy appears in the Legends of Tomorrow episode "The Magnificent Eight". In this story, the boy Wells is dying of consumption, but is cured by a time-travelling Martin Stein.

Literary papers

In 1954, the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign purchased the H. G Wells literary papers and correspondence collection.[115] The University's Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds the largest collection of Wells manuscripts, correspondence, first editions and publications in the United States.[116] Among these is an unpublished material and the manuscripts of such works as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine. The collection includes first editions, revisions, translations. The letters contain general family correspondence, communications, from publishers, material regarding the Fabian Society, and letters from politicians and public figures, most notably George Bernard Shaw and Joseph Conrad.[115]

Bibliography

Notes

- ↑ Science fiction magazine editors Hugo Gernsback and John W. Campbell were the inaugural deceased members of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame, inducted in 1996 and followed annually by fiction writers Wells and Isaac Asimov, C. L. Moore and Robert Heinlein, Abraham Merritt and Jules Verne.[117]

References

- ↑ "Lost daughter of Wells' passion. (writer H.G. Wells) - Version details - Trove". Trove.nla.gov.au. 1996-08-11. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "Death Notice Summaries Available for Listings at A Memory Tree". Amemorytree.co.nz. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "Wells, H. G.". Revised 20 May 2015. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (sf-encyclopedia.com). Retrieved 2015-08-22. Entry by 'JC/BS', John Clute and Brian Stableford.

- 1 2 3 Parrinder, Patrick (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Adam Charles Roberts (2000), "The History of Science Fiction", page 48. In Science Fiction, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19204-8.

- ↑ Siegel, Mark Richard (1988). Hugo Gernsback, Father of Modern Science Fiction: With Essays on Frank Herbert and Bram Stoker. Borgo Pr. ISBN 0-89370-174-2.

- 1 2 "Nomination Database: Herbert G Wells". Nobel Prize.org. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ Robert M. Philmus and David Y. Hughes, ed., H. G. Wells: Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1975), p. 179.

- ↑ Vincent Brome, H. G. Wells: A Biography (London, New York, and Toronto: Longmans, Green, 1951).

- ↑ Vincent Brome, H. G. Wells: A Biography (London, New York, and Toronto: Longmans, Green, 1951), p. 99.

- 1 2 Wells, H. G. (2005) [1905]. Claeys, Gregory; Parrinder, Patrick, eds. A Modern Utopia. Gregory Claeys, Francis Wheen, Andy Sawyer. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-144112-2.

- 1 2 3 Smith, David C. (1986) H. G. Wells: Desperately mortal. A biography. Yale University Press, New Haven and London ISBN 0-300-03672-8

- 1 2 3 Wells, Geoffrey H. (1925). The Works of H. G. Wells. London: Routledge. p. xvi. ISBN 0-86012-096-1. OCLC 458934085.

- ↑ Batchelor, John (1985). H. G. Wells. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-521-27804-X.

- ↑ Reeves, M.S. Round About a Pound a Week. New York: Garland Pub., 1980. ISBN 0-8240-0119-2 Some of the text is available online.

- ↑ "Hampstead: Education". A History of the County of Middlesex. 9: 159–169. 1989. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "A. A. Milne". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ↑ On the 143rd anniversary of Wells's birth Google published a riddle with this location on Google Maps as the solution, but the significance of the 143rd birthday—143 Maybury Road—was not explained: Schofield, Jack (21 September 2009). "HG Wells - Google reveals answer to teaser doodles". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ Batchelor (1985: 165)

- ↑ Lynn, Andrea (2001). Shadow Lovers: The Last Affairs of H. G. Wells. Boulder, CO: Westview. pp. 10; 14; 47 et sec. ISBN 978-0-8133-3394-6.

- ↑ Margaret Drabble (1 April 2005). "A room of her own". The Guardian.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "H. G. Wells". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

- ↑ Wells, Herbert George (1934). Experiment in Autobiography. Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain (Since 1866). Gutenberg.

- ↑ "H. G. Wells' cartoons, a window on his second marriage, focus of new book | Archives | News Bureau". University of Illinois. 31 May 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ Rinkel, Gene and Margaret. The Picshuas of H. G. Wells: A burlesque diary. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006. ISBN 0-252-03045-1 (cloth : acid-free paper).

- ↑ "British Journal for the History of Science". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 17 June 2016

- ↑ The Man Who Invented Tomorrow In 1902, when Arnold Bennett was writing a long article for Cosmopolitan about Wells as a serious writer, Wells expressed his hope that Bennett would stress his "new system of ideas." Wells developed a theory to justify the way he wrote (he was fond of theories), and these theories helped others write in similar ways.

- ↑ D. Behlkar, Ratnakar (2009). Science Fiction: Fantasy and Reality. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 19.

- ↑ Richard Rhodes (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 24. ISBN 0-684-81378-5.

- ↑ "Annual HG Wells Award for Outstanding Contributions to Transhumanism". Web.archive.org. 20 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ Turner, Frank Miller (1993). "Public Science in Britain 1880–1919". Contesting Cultural Authority: Essays in Victorian Intellectual Life. Cambridge University Press. pp. 219–20. ISBN 0-521-37257-7.

- ↑ "The Outline of History—H. G. Wells". Cs.clemson.edu. 20 April 2003. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ "Wells, H. G. 1922. A Short History of the World". Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ A Modern Utopia

- ↑ Cowley, Malcolm. "Outline of Wells's History." The New Republic Vol. 81 Issue 1041, 14 November 1934 (pp. 22–23).

- ↑ At the time of the alleged infringement in 1919-20, unpublished works were protected in Canada under common law.Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 692, note 39.

- ↑ Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 682.

- ↑ McKillop, A. B. (2000) Macfarlane Walter & Ross, Toronto.

- ↑ Deeks, Florence A. (1930s) "Plagiarism?" unpublished typescript, copy in Deeks Fonds, Baldwin Room, Toronto Reference Library, Toronto, Ontario.

- ↑ Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 680, 684.

- ↑ "9. The Last War Cyclone, 1940–50". The shape of things to come: the ultimate revolution (Penguin 2005 ed.). 1933. p. 208. ISBN 0-14-144104-6.

- ↑ Wagar, W. Warren (2004). H. G. Wells: traversing time. Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press. p. 209. ISBN 0-8195-6725-6.

- 1 2 3 Patrick Parrinder and John S. Partington (2005). The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe. pp. 106–108. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ↑ Wells, Frank. H. G. Wells—A Pictorial Biography. London: Jupiter Books, 1977, p. 91.

- ↑ The Miniatures Page. The World of Miniatures—An Overview.

- ↑ Orwell, George (August 1941). "Wells, Hitler and the World State". Horizon. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Chesterton's reference is to the biblical "mess of pottage", implying that Wells had sold out his artistic birthright in mid-career: Rolfe, Christopher; Parrinder, Patrick (1990). H. G. Wells under revision: proceedings of the International H. G. Wells Symposium, London, July 1986. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-945636-05-9.

- ↑ "HG Wells—Diabetes UK". Diabetes.org.uk. 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ "Diabetes UK: Our History". diabetes.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2015

- ↑ Flynn, John L. "The legacy of Orson Welles and the Radio Broadcast". War of the Worlds: from Wells to Spielberg by. Owens Mills, MD: Galactic. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9769400-0-5.

- ↑ "H. G. Wells Dies in London". St. Petersburg Times. 13 August 1946. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ↑ "Calendar". Classics & Cheese. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ↑ "Preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air". Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ↑ West, Anthony. H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life, p. 153. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1984. ISBN 0-09-134540-5.

- ↑ Cole, Margaret (1974). "H. G. Wells and the Fabian Society". In Morris, A. J. Anthony. Edwardian radicalism, 1900–1914: some aspects of British radicalism. London: Routledge. pp. 97–114. ISBN 0-7100-7866-8.

- 1 2 "The Time Machine". Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ H. G. Wells, The Way the World is Going. London, Ernest Benn, 1928, (p. 49).

- 1 2 Siegel, Fred (2013). The Revolt Against the Masses. New York: Encounter Books, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Wells, H. G. The Open Conspiracy: Blue Prints for a World Revolution (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1928), pp. 28, 44, 196.

- ↑ Mazower, Mark, Dark Continent:Europe's Twentieth Century. New York : A. A. Knopf, 1998. ISBN 0679438092 pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Coupland, Philip (October 2000). "H. G. Wells's "Liberal Fascism"". Journal of Contemporary History. 35 (4): 549.

- ↑ Partington, John S. Building Cosmopolis: The Political Thought of H. G. Wells. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0754633837, (p. 16).

- ↑ "H. G. Wells and the uses of Degeneration in Literature". Bbk.ac.uk. 1946-08-17. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ Andrew Clapham, Human Rights:A Very Short Introduction. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780199205523 (pp. 29–31).

- 1 2 H. G. Wells, The Future in America (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1906), p. 201 (Chs. 11 & 12,).

- ↑ Virginia L. Denton, Booker T. Washington and the Adult Education Movement. University Press of Florida, 1993. ISBN 0813011825. pp. 150, 231.

- ↑ What is Coming? A Forecast of Things after the War, London, Cassell, 1916, p. 256.

- ↑ H. G. Wells, The Outline of History, 3rd ed. rev. (NY: Macmillan, 1921), p. 110 (Ch. XII, §§1–2).

- ↑ Susan D. Pennybacker, From Scottsboro to Munich: Race and Political Culture in 1930s Britain Princeton University Press, 2009. ISBN 0691088284, (p. 29).

- 1 2 "What a Zulu Thinks of the English" was reprinted as "The Rights of Man in South Africa" in '42 to '44: A Contemporary Memoir (London, Secker and Warburg, 1944) p. 68–74.

- ↑ Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought, 1900, (London: Chapman & Hall, 1904), p 121.

- ↑ Herbert Wells, The Fate of Homo Sapiens, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1939), p 140.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 130.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 128-129.

- ↑ Cheyette, Bryan. Constructions of "the Jew" in English Literature and Society. Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 143–48.

- 1 2 Lodge, David (2011). A Man of Parts. London: Secker. p. 521. ISBN 9781846554964.

- ↑ H. G. Wells: Why Britain Went To War (10 August 1914). The War Illustrated album de luxe. The story of the great European war told by camera, pen and pencil. The Amalgamated Press, London 1915.

- ↑ Daily Herald, 27 May 1916.

- ↑ Wells, H. G. (1916). "The White Man's Burthen". What Is Coming?: A Forecast of Things after the War. London: Cassell. p. 240. ISBN 0-554-16469-8. OCLC 9446824.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 214.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 216.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 217.

- ↑ Adam Bruno Ulam (2007). "Stalin: The Man and His Era". p. 359. Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2007

- ↑ Experiment in Autobiography, pp. 215, 687–689.

- ↑ "Joseph Stalin and H. G. Wells, Marxism vs. Liberalism: An Interview". Rationalrevolution.net. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ Patrick Parrinder, John S. Partington (2005). "The Reception of H.G. Wells in Europe". p. 102. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ↑ Raymond Plummer, Nothing Need be Ugly Design & Industries Assn., June 1985.

- ↑ Haire, Norman (1924), Rejuvenation : the work of Steinach, Voronoff, and others, G. Allen & Unwin, retrieved 15 April 2013

- ↑ Diana Wyndham. "Norman Haire and the Study of Sex". Foreword by the Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG. Sydney: "Sydney University Press"., 2012, p. 117.

- ↑ 'Human Rights and Public Accountability in H. G. Wells' Functional World State' | John Partington. Academia.edu. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Herbert Wells, The Fate of Homo Sapiens, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1939), p 89-90.

- ↑ Wells, H. G. (1917). "Preface". God the Invisible King. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-585-00604-0. OCLC 261326125. Link to the online book..

- ↑ Wells (1917: "The cosmology of modern religion").

- ↑ Wells, H. G. (1908). First & last things; a confession of faith and rules of life. Putnam. pp. 77–80. OCLC 68958585.

- ↑ The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 291.

- 1 2 John Clute, Science Fiction :The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley London, ISBN 0751302023 (p. 114–15).

- ↑ Andy Sawyer, "[William] Olaf Stapledon (1886–1950)", in Fifty Key Figures in Science Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2010. ISBN 0203874706 (pp. 205–210).

- 1 2 Richard Bleiler, "John Davis Beresford (1873–1947)" in Darren Harris-Fain, ed. British Fantasy and Science Fiction Writers Before World War I. Detroit, MI: Gale Research, 1997. pp. 27–34. ISBN 0810399415.

- ↑ Brian Stableford, "Against the New Gods: The Speculative Fiction of S. Fowler Wright". in Against the New Gods and Other Essays on Writers of Imaginative Fiction Wildside Press LLC, 2009 ISBN 1434457435 (pp. 9–90).

- ↑ "Mitchison, Naomi", in Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature: A Checklist, 1700–1974: With Contemporary Science Fiction Authors II. Robert Reginald, Douglas Menville, Mary A. Burgess. Detroit—Gale Research Company. ISBN 0810310511 p. 1002.

- ↑ Michael D. Sharp, Popular Contemporary Writers, Marshall Cavendish, 2005 ISBN 0761476016 p. 422.

- ↑ Michael R. Collings, Brian Aldiss. Mercer Island, WA : Starmont House, 1986. ISBN 0916732746 p. 60.

- ↑ "Ray Bradbury". Strand Mag.

- ↑ In Memory Yet Green: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov 1920–1954. Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1979. p. 167.

- ↑ "Vertex Magazine Interview". Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012. with Frank Herbert, by Paul Turner, October 1973, Volume 1, Issue 4.

- 1 2 3 John Huntington, "Utopian and Anti-Utopian Logic: H. G. Wells and his Successors". Science Fiction Studies, July 1982.

- 1 2 3 George Hay, "Shiel Versus the Renegade Romantic", in A. Reynolds Morse, Shiel in Diverse Hands: A Collection of Essays. Cleveland, OH: Reynolds Morse Foundation, 1983. pp. 109–113.

- ↑ Rolfe; Parrinder (1990: 226)

- ↑ Lewis, C. S., Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. New York & London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1955. p. 36.

- ↑ R. A. York, The Extension of Life: Fiction and History in the American Novel. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003. ISBN 0838639895. p. 40.

- ↑ "H.G. Wells".

- ↑ Paul Levinson, "Ian, George, and George," Analog Magazine, December, 2013.

- ↑ Booker, M. Keith (2006). Alternate Americas: Science Fiction Film and American Culture. Westport: Praeger Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-275-98395-6.

- 1 2 3 Palumbo, Donald E. (2014). The Monomyth in American Science Fiction Films. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. pp. 33–38. ISBN 978-0-786-47911-5.

- 1 2 "H.G. Wells papers, 1845-1946 | University of Illinois Rare Book & Manuscript Library". University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

- ↑ "H. G. Wells Correspondence". Library Illinois.

- ↑ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. (midamerican.org). 22 February 2008. Retrieved 2015-08-22. Last updated in 2008, this was the official homepage of the Hall of Fame to 2004.

Further reading

- Dickson, Lovat. H. G. Wells: His Turbulent Life & Times. 1969.

- Gilmour, David. The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-374-18702-9); 2003 (paperback, ISBN 0-374-52896-9).

- Gomme, A. W., Mr. Wells as Historian. Glasgow: MacLehose, Jackson, and Co., 1921.

- Gosling, John. Waging the War of the Worlds. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 2009 (paperback, ISBN 0-7864-4105-4).

- Mauthner, Martin. German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940, London: Vallentine and Mitchell, 2007, ISBN 978-0-85303-540-4.

- McLean, Steven. 'The Early Fiction of H. G. Wells: Fantasies of Science'. Palgrave, 2009, ISBN 9780230535626.

- Partington, John S. Building Cosmopolis: The Political Thought of H. G. Wells. Ashgate, 2003, ISBN 978-0754633839.

- Sherborne. Michael. H. G. Wells: Another Kind of Life. London: Peter Owen, 2010, ISBN 978-0-72061-351-3.

- West, Anthony. H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life. London: Hutchinson, 1984.

- Foot, Michael. H. G.: History of Mr. Wells. Doubleday, 1985 (ISBN 978-1-887178-04-4), Black Swan, New edition, Oct 1996 (paperback, ISBN 0-552-99530-4)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Library resources about H. G. Wells |

| By H. G. Wells |

|---|

- H. G. Wells at DMOZ

- H. G. Wells at the Internet Movie Database

Sources—collections

- H. G. Wells papers at University of Illinois

- Works by H. G. Wells at Project Gutenberg

- Works by H. G. Wells at Project Gutenberg Canada

- Works by H. G. Wells at Project Gutenberg Australia, post-1923.

- Works by or about H. G. Wells at Internet Archive

- Works by H. G. Wells at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- H. G. Wells at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- H. G. Wells at Goodreads

- H. G. Wells at the Internet Book List

- A Short History of the World, at bartleby.com.

- Quotes by H. G. Wells

- Free H.G. Wells downloads for iPhone, iPad, Nook, Android, and Kindle in PDF and all popular eBook reader formats (AZW3, EPUB, MOBI) at ebooktakeaway.com

- H G Wells at the British Library

Sources—letters, essays and interviews

- Archive of Wells's BBC broadcasts

- Film interview with H. G. Wells

- "Stephen Crane. From an English Standpoint", by Wells, 1900.

- Rabindranath Tagore: In conversation with H. G. Wells. Rabindranath Tagore and Wells conversing in Geneva in 1930.

- "Introduction", to W. N. P. Barbellion's The Journal of a Disappointed Man, by Wells, 1919.

- "Woman and Primitive Culture", by Wells, 1895.

- Letter, to M. P. Shiel, by Wells, 1937.

- New Statesman – In the footsteps of H G Wells at www.newstatesman.com, H. G. Wells called for a Human Rights Act.

- H. G. Wells, The Open Conspiracy (1933)

Biography

-

"Wells, Herbert George". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Wells, Herbert George". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. - "H. G. Wells". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Parrinder, Patrick (2011) [2004]. "Wells, Herbert George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36831. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "H. G. Wells biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

Critical essays

- An introduction to The War of the Worlds by Iain Sinclair on the British Library's Discovering Literature website.

- "An Appreciation of H. G. Wells", by Mary Austin, 1911.

- "Socialism and the Family" (1906) by Belfort Bax, Part 1, Part 2.

- "H. G. Wells warned us how it would feel to fight a War of the Worlds", by Niall Ferguson, in The Telegraph, 24 Jun 2005.

- "H. G. Wells's Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Re-assessment", by W. Boyd Rayward, in Journal of the American Society for Information Science 50 (15 May 1999): 557–579

- "Mr H. G. Wells and the Giants", by G. K. Chesterton, from his book Heretics (1908).

- "The Internet: a world brain?", by Martin Gardner, in Skeptical Inquirer, Jan–Feb 1999.

- "Science Fiction: The Shape of Things to Come", by Mark Bould, in The Socialist Review, May 2005.

- "Who needs Utopia? A dialogue with my utopian self (with apologies, and thanks, to H. G. Wells)", by Gregory Claeys in Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal, no 1, Spring 2006.

- "When H. G. Wells Split the Atom: A 1914 Preview of 1945", by Freda Kirchwey, in The Nation, posted 4 Sep 2003 (original 18 Aug 1945 issue).

- "Evil is in the Eye of the Beholder: Threatening Children in Two Edwardian Speculative Satires," by George M. Johnson. Science Fiction Studies. Vol. 41, No.1 (March 2014): 26-44.

- "Wells, Hitler and the World State", by George Orwell. First published: Horizon. GB, London. Aug 1941.

- "War of the Worldviews", by John J. Miller, in The Wall Street Journal Opinion Journal, 21 Jun 2005.

- "Wells' Autobiography", by John Hart, from New International, Vol.2 No.2, Mar 1935, pp. 75–76

- "History in the Science Fiction of H. G. Wells", by Patrick Parrinder, Cycnos, 22.2 (2006).

- "From the World Brain to the Worldwide Web", by Martin Campbell-Kelly, Gresham College Lecture, 9 Nov 2006.

- "The Beginning of Wisdom: On Reading H. G. Wells", by Vivian Gornick, "Boston Review", 31.1 (2007).

- John Hammond, The Complete List of Short Stories of H. G. Wells

- Biography at a website examining the legacy of The War Of The Worlds

- "H. G. Wells Predictions Ring True, 143 Years Later" at National Geographic

- "H.G. Wells,the man I knew" Obituary of Wells by George Bernard Shaw, at the New Statesman

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Galsworthy |

International President of PEN International 1933–1936 |

Succeeded by Jules Romains |