Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, excepting the 1912 split in which Democrats held the White House for eight years. American history texts usually call it the Progressive Era. The concept was introduced under the name "System of 1896" by E.E. Schattschneider in 1960, and the numbering scheme was added by political scientists in the mid-1960s.[1]

The period featured a transformation from the issues of the Third Party System, which had focused on the American Civil War, Reconstruction, race and monetary issues. The era began in the severe depression of 1893 and the extraordinarily intense election of 1896. It included the Progressive Era, World War I, and the start of the Great Depression. The Great Depression caused a realignment that produced the Fifth Party System, dominated by the Democratic New Deal Coalition until the 1960s.

The central domestic issues concerned government regulation of railroads and large corporations ("trusts"), the money issue (gold versus silver), the protective tariff, the role of labor unions, child labor, the need for a new banking system, corruption in party politics, primary elections, direct election of senators, racial segregation, efficiency in government, women's suffrage, and control of immigration. Foreign policy centered on the 1898 Spanish–American War, Imperialism, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, and the creation of the League of Nations. Dominant personalities included presidents William McKinley (R), Theodore Roosevelt (R) and Woodrow Wilson (D), three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan (D), and Wisconsin's progressive Republican Robert M. LaFollette.

Beginnings

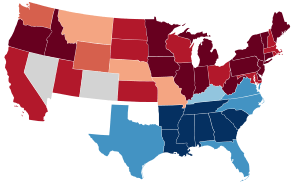

The period began with the realignment of 1894–96. The overwhelming Republican victory in 1896 over William Jennings Bryan and his Democratic Party, repeated in 1900, restored business confidence, inaugurated a long epoch of prosperity (shown in the table), and swept away most of the issues and personalities of the Third Party System. Most voting blocs continued unchanged, but some realignment took place, giving Republicans dominance in the industrial Northeast and new strength in the border states. Thus the way was clear for the Progressive Movement to impose a new way of thinking and a new agenda for politics. During this period, a generational shift took place as the veterans of the Civil War aged out and were replaced by a younger generation more concerned with social justice and curbing the inequalities of industrial capitalism. In addition, the influx of Jewish and Catholic immigrants from Europe caused a gradual alteration of traditional WASP-dominated power blocs. The Democratic Party, after largely being excluded from national politics in the decades following the Civil War, would see a resurgence during this period thanks to the new immigrant voting blocs, and Woodrow Wilson's presidency marked a watershed as a new generation of Democrats without the baggage of slavery and secession came to power. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, after a brief fling with progressivism under Theodore Roosevelt, would quickly reassert themselves as the party of big business and laisse-faire capitalism.

Economic trends

Real GDP per capita

| Year | GDP |

|---|---|

| 1892 | 104 |

| 1896 | 100 |

| 1900 | 114 |

| 1904 | 121 |

| 1908 | 119 |

| 1912 | 139 |

| 1916 | 145 |

| 1920 | 147 |

| 1924 | 164 |

| 1928 | 173 |

| 1932 | 133 |

Progressive reforms

Alarmed at the new rules of the game for campaign funding, the Progressives launched investigations and exposures (by the "muckraker" journalists) into corrupt links between party bosses and business. New laws and constitutional amendments weakened the party bosses by installing primaries and directly electing senators.[2] Theodore Roosevelt shared the growing concern with business influence on government. When William Howard Taft appeared to be too cozy with pro-business conservatives in terms of tariff and conservation issues, Roosevelt broke with his old friend and his old party. He crusaded for president in 1912 at the head of an ill-fated "Bull Moose" Progressive party. TR's schism helped elect Woodrow Wilson in 1912 and left pro-business conservatives as the dominant force in the GOP. The latter elected Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. In 1928 Herbert Hoover became the last president of the Fourth Party System.

Many of the Progressives, especially in the Democratic Party, supported labor unions. Unions did become important components of the Democratic Party during the Fifth Party System. However, historians have long debated why no Labor Party emerged in the United States, in contrast to Western Europe.[3]

The Great Depression that began in 1929 spoiled the nation's optimism and ruined Republican chances. In long-term perspective Al Smith in 1928 started a voter realignment—a new coalition—based among ethnics and big cities that spelled the end of classless politics of the Fourth Party System and helped usher in the Fifth Party System or New Deal coalition of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[4] As one political scientist explains, "The election of 1896 ushered in the Fourth Party System ... [but] not until 1928, with the nomination of Al Smith, a northeastern reformer, did Democrats make gains among the urban, blue-collar, and Catholic voters who were later to become core components of the New Deal coalition and break the pattern of minimal class polarization that had characterized the Fourth Party System."[5] In 1932 the landslide victory of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt led to the New Deal coalition that dominated the Fifth Party System, after 1932.

Women's suffrage and feminism

Gustafson (1997) shows that women vigorously define their role in political parties from the 1880s to 1920. Traditionally viewed as nonpartisan, women generally formed auxiliaries to the Republican and Democratic parties. The formation of the Progressive Party in 1912 offered women a chance for equality. Progressive party supporter Jane Addams openly advocated women's partisanship. After the Progressive Party loss in 1912, partisan women continued to form auxiliaries in the major parties. After 1920, inclusion and power in political parties persisted as issues for partisan women. Suffragists shifted from an emphasis on their right to vote to a new emphasis on the need for women to purify politics and guide policy toward education. The suffrage movement gained strength during the World War, and at the end women received the vote, in a major change in the rules of the game.

Prohibition

In most of the country prohibition was of central importance in progressive politics before World War I, with a strong religious and ethnic dimension.[6] Most pietistic Protestants were "dries" who advocated prohibition as a solution to social problems; they included Methodists, Congregationalists, Disciples, Baptists, Presbyterians, Quakers, and Scandinavian Lutherans. On the "wet" side, Episcopalians, Irish Catholics, German Lutherans and German Catholics attacked prohibition as a menace to their social customs and personal liberty. Prohibitionists supported direct democracy to enable voters to bypass the state legislature in lawmaking. In the North, the Republican Party championed the interests of the prohibitionists, while the Democratic Party represented ethnic group interests. In the South, the Baptist and Methodist churches played a major role in forcing the Democratic party to support prohibition. After 1914 the issue shifted to the Germans' opposition to Woodrow Wilson's foreign policy. In the 1920s, however, the sudden, unexpected outburst of big city crime associated with bootlegging undermined support for prohibition, and the Democrats took up the cause for repeal, finally succeeding in 1932.[7][8][9]

International policies

The Spanish–American War in 1898 precipitated the end of the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean and the Pacific, with the 1898 Treaty of Paris giving the US control over the former Spanish colonies. Permanent ownership of the Philippines was a major issue in the 1900 presidential election. Bryan, although strongly supportive of the war against Spain, denounced the permanent acquisition of the Philippines, which was strongly defended by Republicans, especially the Vice-Presidential nominee Theodore Roosevelt.[10] President Roosevelt in 1904 boasted of his success in gaining control of the Panama Canal, in 1903. Democrats attacked the move, but their attempt to apologize to Colombia failed.[11]

The United States also appeared on the world scene in the last years of World War I. President Woodrow Wilson tried to negotiate peace in Europe, but when Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare against American shipping in early 1917 he called on Congress to declare war. Ignoring military affairs, he focused on diplomacy and finance. On the home front he began the first effective draft in 1917, raised billions through Liberty loans, imposed an income tax on the wealthy, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union growth, supervised agriculture and food production through the Food and Fuel Control Act, took over control of the railroads, and suppressed left-wing anti-war movements. Like the European states, the United States experimented with a war economy. In 1918, Wilson advocated various international reforms in the Fourteen Points, among them public diplomacy, freedom of navigation, "equality of trade conditions" and removal of economic barriers, an "impartial adjustment of all colonial claims," the creation of a Polish state, and, most important, the creation of an association of nations. The latter would become the League of Nations. The League became highly controversial as Wilson and the Republicans refused to compromise. Voters in 1920 showed little support for the League and the U.S. never joined. Peace was a major political theme in the 1920s (especially because women were now voting). Under the Harding administration, the Washington Naval Conference of 1922 achieved significant naval disarmament for ten years.

The Roaring Twenties were marked, on the international scene, by the problem of the economic reparations due by Germany to France and Great Britain, as well as by various irredentism claims. The US acted as mediators in this conflict, first with the Dawes Plan in 1924, then the Young Plan in 1929.

See also

- Third Party System, 1850s–1890s

- Fifth Party System, 1930s–1960s

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- Political parties in the United States

Bibliography

- Blum, John Morton. The Progressive Presidents: Roosevelt, Wilson, Roosevelt, Johnson (1980)

- Burner, David. Herbert Hoover: A Public Life. (1979).

- Burnham, Walter Dean, "The System of 1896: An Analysis," in Paul Kleppner, et al., The Evolution of American Electoral Systems, Greenwood. (1983)

- Burnham, Walter Dean. "Periodization Schemes and 'Party Systems': The "System of 1896" as a Case in Point," Social Science History, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 263–314.online at JSTOR

- Carter, Susan, ed. Historical Statistics of the U.S. (Millennium Edition) (2006) series Ca11

- Cherny, Robert W. A Righteous Cause: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (1994)

- Cooper, John Milton The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. (1983) a dual biography

- Craig, Douglas B. After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920–1934 (1992)

- Degler, Carl N. (1964). "American Political Parties and the Rise of the City: An Interpretation". Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 51 (1): 41–59. doi:10.2307/1917933. JSTOR 1917933.

- Edwards, Rebecca. Angels in the Machinery: Gender in American Party Politics from the Civil War to the Progressive Era (1997)

- Folsom, Burton W. "Tinkerers, Tipplers, and Traitors: Ethnicity and Democratic Reform in Nebraska During the Progressive Era." Pacific Historical Review 1981 50(1): 53-75. ISSN 0030-8684

- Gosnell, Harold F. Boss Platt and His New York Machine: A Study of the Political Leadership of Thomas C. Platt, Theodore Roosevelt, and Others (1924)

- Gould, Lewis L. America in the Progressive Era, 1890–1914 (2000)

- Gould, Lewis L. Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics (2008) excerpt and text search

- Gustafson, Melanie. "Partisan Women in the Progressive Era: the Struggle for Inclusion in American Political Parties." Journal of Women's History 1997 9(2): 8–30. ISSN 1042-7961 Fulltext online at SwetsWise and Ebsco.

- Harbaugh, William Henry. The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. (1963)

- Harrison, Robert. Congress, Progressive Reform, and the New American State (2004)

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. (1955)

- Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition (1948), chapters on Bryan, Roosevelt, Wilson and Hoover

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 (1971)

- Jensen, Richard. Grass Roots Politics: Parties, Issues, and Voters, 1854–1983 (1983)

- Keller, Morton. Affairs of State: Public Life in Late Nineteenth Century America (1977)

- Kleppner, Paul. Continuity and Change in Electoral Politics, 1893–1928 Greenwood. 1987

- Lawrence, David G. (1996). The Collapse of the Democratic Presidential Majority: Realignment, Dealignment, and Electoral Change from Franklin Roosevelt to Bill Clinton. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8984-4.

- Lee, Demetrius Walker, "The Ballot as a Party-System Switch: The Role of the Australian Ballot in Party-System Change and Development in the USA," Party Politics, Vol. 11, No. 2, 217–241 (2005)

- Lichtman, A. J. "Critical elections theory and the reality of American presidential politics, 1916–40." American Historical Review (1976) 81: 317–348. in JSTOR

- Lichtman, Allan J. Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928 (1979).

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917 (1972) standard political history of the era

- Link, Arthur. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917 (1963)

- McSeveney, Samuel T. "The Fourth Party System and Progressive Politics", in. L. Sandy Maisel and William Shade (eds) Parties and Politics in American History (1994)

- Mahan, Russell L. "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896" White House Studies 2003 3(2): 215–227. ISSN 1535-4768

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex (2002), detailed biography of Roosevelt as president 1901–1909

- Mowry, George. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900–1912. (1954)

- Sanders, Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917 (1999). argues the Democrats were the true progressives and GOP was mostly conservative

- Sarasohn, David. The Party of Reform: Democrats in the Progressive Era (1989), covers 1910–1930.

- Sundquist, James L. Dynamics of the Party System, (2nd ed. 1983)

- Ware, Alan. The American Direct Primary: Party Institutionalization and Transformation in the North (2002)

- Williams, R. Hal. Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 (2010) excerpt and text search

Primary sources

- Bryan, William Jennings. First Battle (1897), speeches from 1896 campaign.

- Ginger, Ray, ed. William Jennings Bryan; Selections (1967).

- LaFollette, Robert. Autobiography (1913)

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Autobiography (1913)

- Whicher, George F., ed. William Jennings Bryan and the Campaign of 1896 (1953), primary and secondary sources.

References

- ↑ To cite a standard political science college textbook: "Scholars generally agree that realignment theory identifies five distinct party systems with the following approximate dates and major parties: 1. 1796–1816, First Party System: Jeffersonian Republicans and Federalists; 2. 1840–1856, Second Party System: Democrats and Whigs; 3. 1860–1896, Third Party System: Republicans and Democrats; 4. 1896–1932, Fourth Party System: Republicans and Democrats; 5. 1932–, Fifth Party System: Democrats and Republicans." Robert C. Benedict, Matthew J. Burbank and Ronald J. Hrebenar, Political Parties, Interest Groups and Political Campaigns. Westview Press. 1999. Page 11.

- ↑ Ware (2002)

- ↑ Robin Archer, Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States? (Princeton University Press, 2007)

- ↑ Degler (1964)

- ↑ Lawrence (1996) p. 34.

- ↑ Norman Clark, Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition (1976)

- ↑ Sabine N. Meyer, We Are What We Drink: The Temperance Battle in Minnesota (U of Illinois Press, 2015)

- ↑ Burton W. Folsom, "Tinkerers, Tipplers, and Traitors: Ethnicity and Democratic Reform in Nebraska During the Progressive Era." Pacific Historical Review (1981) 50#1 pp: 53–75 in JSTOR

- ↑ Michael A. Lerner, Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City (2009)

- ↑ Thomas A. Bailey, "Was the Presidential Election of 1900 a Mandate on Imperialism?." Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1937): 43–52.in JSTOR

- ↑ Thomas E. Morrissey (2009). Donegan and the Panama Canal. p. 298.

External links

- bibliography

- John C. Green and Paul S. Herrnson. "Party Development in the Twentieth Century: Laying the Foundations for Responsible Party Government?" (2000) online version

.svg.png)