Great Depression in the United States

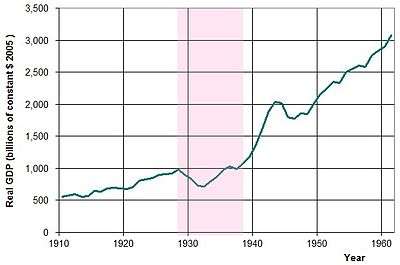

The Great Depression began in August 1929, when the United States economy first went into an economic recession. Although the country spent two months with declining GDP, it was not until the Wall Street Crash in October 1929 that the effects of a declining economy were felt, and a major worldwide economic downturn ensued. The market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, deflation, plunging farm incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth and personal advancement. Although its causes are still uncertain and controversial, the net effect was a sudden and general loss of confidence in the economic future.[1]

The usual explanations include numerous factors, especially high consumer debt, ill-regulated markets that permitted overoptimistic loans by banks and investors, and the lack of high-growth new industries,[2] all interacting to create a downward economic spiral of reduced spending, falling confidence, and lowered production.[3]

Industries that suffered the most included construction, agriculture as dust-bowl conditions persisted in the agricultural heartland, shipping, mining, and logging as well as durable goods like automobiles and appliances that could be postponed. The economy reached bottom in the winter of 1932–33; then came four years of very rapid growth until 1937, when the Recession of 1937 brought back 1934 levels of unemployment.[4]

The Depression caused major political changes in America. Three years into the depression, President Herbert Hoover, widely blamed for not doing enough to combat the crisis, lost the election of 1932 to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in a landslide. Roosevelt's economic recovery plan, the New Deal, instituted unprecedented programs for relief, recovery and reform, and brought about a major realignment of American politics.

The Depression also resulted in an increase of emigration of people to other countries for the first time in American history. For example, some immigrants went back to their native countries, and some native US citizens went to Canada, Australia, and South Africa. It also resulted in the mass migration of people from badly hit areas in the Great Plains and the South to places such as California and the North, respectively (see Okies and the Great Migration of African Americans).[5][6] Racial tensions also increased during this time. By the 1940s immigration had returned to normal, and emigration declined. A well-known example of an emigrant was Frank McCourt, who went to Ireland, as recounted in his book Angela's Ashes.

The memory of the Depression also shaped modern theories of economics and resulted in many changes in how the government dealt with economic downturns, such as the use of stimulus packages, Keynesian economics, and Social Security. It also shaped modern American literature, resulting in famous novels such as John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men.

There are multiple originating issues: what factors set off the first downturn in 1929, what structural weaknesses and specific events turned it into a major depression, how the downturn spread from country to country, and why the economic recovery was so prolonged.[7]

Banks began to fail in October 1930 (one year after the crash) when farmers defaulted on loans. There was no federal deposit insurance during that time as bank failures were considered quite common. This worried depositors that they might have a chance of losing all their savings, therefore, people started to withdraw money and changed it into currency. As deposits taken out from the bank increased, the money supply decreased because the money multiplier worked in reverse, forcing banks to liquidate assets (such as call in loans rather than create new loans.)[8] This caused the money supply to shrink and the economy to contract and a significant decrease in aggregate investment. The decreased the money supply further aggravated price deflation, putting further pressure on already struggling businesses.

The US government's commitment to the gold standard prevented it from engaging in expansionary monetary policy. High interest rates needed to be maintained, in order to attract international investors who bought foreign assets with gold. However, the high interest also inhibited domestic business borrowing. The US interest rates were also affected by France's decision to raise their interest rates to attract gold to their vaults. In theory, the U.S. would have two potential responses to that: Allow the exchange rate to adjust, or increase their own interest rates to maintain the gold standard. At the time, the U.S. was pegged to the gold standard. Therefore, Americans converted their dollars into francs to buy more French assets, the demand for the U.S. dollar fell, and the exchange rate increased. The only thing the US could do to get back into equilibrium was increase interest rates.

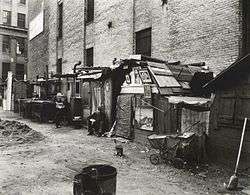

The depression in the cities

One visible effect of the depression was the advent of Hoovervilles, which were ramshackle assemblages on vacant lots of cardboard boxes, tents, and small rickety wooden sheds built by homeless people. Residents lived in the shacks and begged for food or went to soup kitchens.The term was coined by Charles Michelson, publicity chief of the Democratic National Committee, who referred sardonically to President Herbert Hoover whose policies he blamed for the depression.[9]

Unemployment reached 25 percent in the worst days of 1932-33, but it was unevenly distributed. Job losses were less severe among women, workers in nondurable industries (such as food and clothing), services and sales workers, and those employed by the government. Unskilled inner city men had much higher unemployment rates. Age also played a factor: young people had a hard time getting their first job, and men over the age of 45, if they lost their job, would rarely find another one because employers had their choice of younger men. Millions were hired in the Great Depression, but men with weaker credentials were never hired, and fell into a long-term unemployment trap. The migration that brought millions of farmers and townspeople to the bigger cities in the 1920s suddenly reversed itself, as unemployment made the cities unattractive, and the network of kinfolk and more ample food supplies made it wise for many to go back.[10] City governments in 1930-31 tried to meet the depression by expanding public works projects, as president Herbert Hoover strongly encouraged. However, tax revenues were plunging, and the cities as well as private relief agencies were totally overwhelmed by 1931; no one was able to provide significant additional relief. People fell back on the cheapest possible relief, soup kitchens which provided free meals for anyone who showed up.[11] After 1933 new sales taxes and infusions of federal money helped relieve the fiscal distress of the cities, but the budgets did not fully recover until 1941.

The federal programs launched by Hoover and greatly expanded by President Roosevelt's New Deal used massive construction projects to try to jump start the economy and solve the unemployment crisis. The alphabet agencies ERA, CCC, FERA, WPA and PWA built and repaired the public infrastructure in dramatic fashion, but did little to foster the recovery of the private sector. FERA, CCC and especially WPA focused on providing unskilled jobs for long-term unemployed men.

The Democrats won easy landslide victories in 1932 and 1934, and an even bigger one in 1936; the hapless Republican Party seemed doomed. The Democrats capitalized on the magnetic appeal of Roosevelt to urban America. The key groups were low skilled ethnics, especially Catholic, Jewish, and black people. The Democrats promised and delivered in terms of beer, political recognition, labor union membership, and relief jobs. The cities' political machines were stronger than ever, for they mobilized their precinct workers to help families who needed help the most navigate the bureaucracy and get on relief. FDR won the vote of practically every demographic in 1936, including taxpayers, small business and the middle class. However, the Protestant middle class voters turned sharply against him after the recession of 1937-38 undermined repeated promises that recovery was at hand. Historically, local political machines were primarily interested in controlling their wards and citywide elections; the smaller the turnout on election day, the easier it was to control the system. However, for Roosevelt to win the presidency in 1936 and 1940, he needed to carry the electoral college and that meant he needed the largest possible majorities in the cities to overwhelm the out state vote. The machines came through for him.[12] The 3.5 million voters on relief payrolls during the 1936 election cast 82% percent of their ballots for Roosevelt. The rapidly growing, energetic labor unions, chiefly based in the cities, turned out 80% for FDR, as did Irish, Italian and Jewish communities. In all, the nation's 106 cities over 100,000 population voted 70% for FDR in 1936, compared to his 59% elsewhere. Roosevelt worked very well with the big city machines, with the one exception of his old nemesis, Tammany Hall in Manhattan. There he supported the complicated coalition built around the nominal Republican Fiorello La Guardia, and based on Jewish and Italian voters mobilized by labor unions.[13]

In 1938, the Republicans made an unexpected comeback, and Roosevelt's efforts to purge the Democratic Party of his political opponents backfired badly. The conservative coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats took control of Congress, outvoted the urban liberals, and halted the expansion of New Deal ideas. Roosevelt survived in 1940 thanks to his margin in the Solid South and in the cities. In the North the cities over 100,000 gave Roosevelt 60% of their votes, while the rest of the North favored Willkie 52%-48%.[14]

With the start of full-scale war mobilization in the summer of 1940, the economies of the cities rebounded. Even before Pearl Harbor, Washington pumped massive investments into new factories and funded round-the-clock munitions production, guaranteeing a job to anyone who showed up at the factory gate.[15] The war brought a restoration of prosperity and hopeful expectations for the future across the nation. It had the greatest impact on the cities of the West Coast, especially Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle.[16]

Global comparison of severity

The Great Depression began in the United States of America and quickly spread worldwide.[17] It had severe effects in countries both rich and poor. Personal income, consumption, industrial output, tax revenue, profits and prices dropped, while international trade plunged by more than 50%. Unemployment in the U.S. rose to 25%, and in some countries rose as high as 33%.[18]

Cities all around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by approximately 60%.[19][20] Facing plummeting demand with few alternate sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as grain farming, mining and logging, as well as construction, suffered the most.[21]

Most economies started to recover by 1933–34. However, in the U.S. and some others the negative economic impact often lasted until the beginning of World War II, when war industries stimulated recovery.[22]

There is little agreement on what caused the Great Depression, and the topic has become highly politicized. At the time the great majority of economists around the world recommended the "orthodox" solution of cutting government spending and raising taxes. However, British economist John Maynard Keynes advocated large-scale government deficit spending to make up for the failure of private investment. No major nation adopted his policies in the 1930s.[23]

Europe

- Europe as a whole was badly hit, in both rural and industrial areas. Democracy was discredited and the left often tried a coalition arrangement between Communists and Socialists, who previously had been harsh enemies. Right wing movements sprang up, often following Italy's fascist mode.[24]

- As the Great Depression worsened, Labour lost power in Britain and a coalition government dominated by conservatives came to power in 1931, and remained in power until 1945. There were no programs in Britain comparable to the New Deal.

- In France, the "Popular Front" government of Socialists with some Communist support, was in power 1936–1938. It launched major programs favoring labor and the working class, but engendered stiff opposition.

- Germany during the Weimar Republic had fully recovered and was prosperous in the late 1920s. The Great Depression hit in 1929 and was severe. The political system descended into violence and the Nazis under Hitler came to power through elections in early 1933. Economic recovery was pursued through autarky, pressure on economic partners, wage controls, price controls, and spending programs such as public works and, especially, military spending.

- Spain saw mounting political crises that led in 1936–39 to civil war.

- In Benito Mussolini's Italy, the economic controls of his corporate state were tightened. The economy was never prosperous.

- The Soviet Union was mostly isolated from the world trading system during the 1930s. To force peasants into industrial jobs in the cities, food was stripped from rural areas, and millions died of starvation. The dictator Joseph Stalin purged nearly all the old Bolsheviks, and killed or imprisoned hundreds of thousands of presumed enemies.

Canada and the Caribbean

- In Canada, Between 1929 and 1939, the gross national product dropped 40%, compared to 37% in the U.S. Unemployment reached 28% at the depth of the Depression in 1929 and 1930,[25] while wages bottomed out in 1933.[26] Many businesses closed, as corporate profits of C$396 million in 1929 turned into losses of $98 million in 1933. Exports shrank by 50% from 1929 to 1933. Worst hit were areas dependent on primary industries such as farming, mining and logging, as prices fell and there were few alternative jobs. Families saw most or all of their assets disappear and their debts became heavier as prices fell. Local and provincial government set up relief programs but there was no nationwide New-Deal-like program. The Conservative government of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett retaliated against the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act by raising tariffs against the U.S. but lowered them on British Empire goods. Nevertheless, the economy suffered. In 1935, Bennett proposed a series of programs that resembled the New Deal; but was defeated in the elections of that year and no such programs were passed.[27]

- Cuba and the Caribbean saw its greatest unemployment during the 1930s because of a decline in exports to the U.S., and a fall in export prices.

Asia

- China was at war with Japan during most of the 1930s, in addition to internal struggles between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists and Mao Zedong's communists.

- Japan's economy expanded at the rate of 5% of GDP per year after the years of modernization. Manufacturing and mining came to account for more than 30% of GDP, more than twice the value for the agricultural sector. Most industrial growth, however, was geared toward expanding the nation's military power. Beginning in 1937 much of Japan's energy was focused on a large-scale war and occupation of China.

Australia and New Zealand

- In Australia, 1930s conservative and Labor-led governments concentrated on cutting spending and reducing the national debt.

- In New Zealand, a series of economic and social policies similar to the New Deal were adopted after the election of the first Labour Government in 1935.[28]

Political results of the depression

Top right: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was responsible for initiatives and programs collectively known as the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal.

In the "First New Deal" of 1933–34, programs, such as the National Recovery Administration (NRA), sought to stimulate demand and provide work and relief through increased government spending. To end Deflation the Gold standard was suspended and a series of panels comprising business leaders in each industry set regulations which ended what was called "cut-throat competition," believed to be responsible for forcing down prices and profits nationwide.[29]

The NRA, which ended in March 1935 when the Supreme Court of the United States declared it unconstitutional, had these roles:[30]

- Setting minimum prices and wages and competitive conditions in all industries. (NRA)[31]

- Encouraging unions that would raise wages, to increase the purchasing power of the working class.

- Cutting farm production so as to raise prices and make it possible to earn a living in farming (done by the AAA and successor farm programs).

In 1934–36, during what the U.S. Department of State calls the "Second New Deal," Roosevelt and his party added social security; the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a national relief agency; and, through the National Labor Relations Board, a strong stimulus to the growth of labor unions. Unemployment fell by ⅔ in Roosevelt's first term (from 25% to 9%, 1933–1937), but fell continually until the war.[32]

In 1929, federal expenditures constituted only 20% of the GDP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditures tripled, but the national debt remained about level at 40% of GDP. (The debt as proportion of GDP rose under Hoover from 20% to 40%; the debt as % of GDP soared during the war years, 1941–45.) Following the Recession of 1937 and the debate on "court packing", southern Democrats joined with Republicans in a conservative coalition to stop further expansion of the New Deal. By 1943, during World War II, all of the relief programs had ended with the exception of Social Security. The labor laws were revised by conservatives in the Taft Hartley Act of 1947.

The New Deal was, and still is, widely debated.[33][34] The Great Depression and the New Deal remain a benchmark amongst economists for evaluating severe financial downturns, such as the economic crisis of 2008.[35]

Recession of 1937

By 1936, all the main economic indicators had regained the levels of the late 1920s, except for unemployment, which remained high. In 1937, the American economy unexpectedly fell, lasting through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. Unemployment jumped from 14.3% in 1937 to 19.0% in 1938.[36] A contributing factor to the Recession of 1937 was a tightening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve doubled reserve requirements between August 1936 and May 1937[37] leading to a contraction in the money supply.

The Roosevelt Administration reacted by launching a rhetorical campaign against monopoly power, which was cast as the cause of the depression, and appointing Thurman Arnold to break up large trusts; Arnold was not effective, and the campaign ended once World War II began and corporate energies had to be directed to winning the war.[38] By 1939, the effects of the 1937 recession had disappeared. Employment in the private sector recovered to the level of the 1936 and continued to increase until the war came and manufacturing employment leaped from 11 million in 1940 to 18 million in 1943.[39]

Another response to the 1937 deepening of the Great Depression had more tangible results. Ignoring the pleas of the Treasury Department, Roosevelt embarked on an antidote to the depression, reluctantly abandoning his efforts to balance the budget and launching a $5 billion spending program in the spring of 1938 in an effort to increase mass purchasing power.

Business-oriented observers explained the recession and recovery in very different terms from the Keynesian economists. They argued the New Deal had been very hostile to business expansion in 1935–37. They said it had encouraged massive strikes which had a negative impact on major industries and had threatened anti-trust attacks on big corporations. But all those threats diminished sharply after 1938. For example, the antitrust efforts fizzled out without major cases. The CIO and AFL unions started battling each other more than corporations, and tax policy became more favorable to long-term growth.[40]

On the other hand, according to economist Robert Higgs, when looking only at the supply of consumer goods, significant GDP growth only resumed in 1946. (Higgs does not estimate the value to consumers of collective goods like victory in war)[41] To Keynesians, the war economy showed just how large the fiscal stimulus required to end the downturn of the Depression was, and it led, at the time, to fears that as soon as America demobilized, it would return to Depression conditions and industrial output would fall to its pre-war levels. The incorrect prediction by Alvin Hansen and other Keynesians that a new depression would start after the war failed to take account of pent-up consumer demand as a result of the Depression and World War.[42]

Afterward

The government began heavy military spending in 1940, and started drafting millions of young men that year;[43] by 1945, 17 million had entered service to their country. But that was not enough to absorb all the unemployed. During the war, the government subsidized wages through cost-plus contracts. Government contractors were paid in full for their costs, plus a certain percentage profit margin. That meant the more wages a person was paid the higher the company profits since the government would cover them plus a percentage.[44]

Using these cost-plus contracts in 1941–1943, factories hired hundreds of thousands of unskilled workers and trained them, at government expense. The military's own training programs concentrated on teaching technical skills involving machinery, engines, electronics and radio, preparing soldiers and sailors for the post-war economy.[45]

Structural walls were lowered dramatically during the war, especially informal policies against hiring women, minorities, and workers over 45 or under 18. (See FEPC) Strikes (except in coal mining) were sharply reduced as unions pushed their members to work harder. Tens of thousands of new factories and shipyards were built, with new bus services and nursery care for children making them more accessible. Wages soared for workers, making it quite expensive to sit at home. Employers retooled so that unskilled new workers could handle jobs that previously required skills that were now in short supply. The combination of all these factors drove unemployment below 2% in 1943.[46]

Roosevelt's declining popularity in 1938 was evident throughout the US in the business community, the press, and the Senate and House. Many were labeling the recession the "Roosevelt Recession". In late December 1938, Roosevelt looked to gain popularity with the American people, and try to regain the nation's confidence in the economy. His decision that December to name Harry Hopkins as Secretary of Commerce was an attempt to achieve the confidence he so badly needed. The appointment came as a surprise to most because of Hopkins' lack of business experience, but proved to be vastly important in shaping the years following the recession.[47]

Hopkins made it his mission to strengthen ties between the Roosevelt administration and the business community. While Roosevelt believed in complete reform (The New Deal), Hopkins took a more administrative position; he felt that recovery was imperative and that The New Deal would continue to hinder recovery. With support from Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr, popular support for recovery, rather than reform, swept the nation. By the end of 1938 reform had been struck down, as no new reform laws were passed.[47]

The economy in America was now beginning to show signs of recovery and the unemployment rate was lowering following the abysmal year of 1938. The biggest shift towards recovery, however, came with the decision of Germany to invade France at the beginning of WWII. After France had been defeated, the U.S. economy would skyrocket in the months following. France's defeat meant that Britain and other allies would look to the U.S. for large supplies of materials for the war.[48]

The need for these war materials created a huge spurt in production, thus leading to promising amount of employment in America. Moreover, Britain chose to pay for their materials in gold. This stimulated the gold inflow and raised the monetary base, which in turn, stimulated the American economy to its highest point since the summer of 1929 when the depression began.[48]

By the end of 1941, before American entry into the war, defense spending and military mobilization had started one of the greatest booms in American history thus ending the last traces of unemployment.[48]

Facts and figures

Fireside Chat 1 On the Banking Crisis

Roosevelt's first Fireside Chat on the Banking Crisis (March 12, 1933) |

Effects of depression in the U.S.:[49]

- 13 million people became unemployed. In 1932, 34 million people belonged to families with no regular full-time wage earner.[50]

- Industrial production fell by nearly 45% between 1929 and 1932.

- Homebuilding dropped by 80% between the years 1929 and 1932.

- In the 1920s, the banking system in the U.S. was about $50 billion, which was about 50% of GDP.[51]

- From 1929 to 1932, about 5,000 banks went out of business.

- By 1933, 11,000 of the US' 25,000 banks had failed.[52]

- Between 1929 and 1933, U.S. GDP fell around 30%, the stock market lost almost 90% of its value.[53]

- In 1929, the unemployment rate averaged 3%.[54]

- In 1933, 25% of all workers and 37% of all nonfarm workers were unemployed.[55]

- In Cleveland, the unemployment rate was 50%; in Toledo, Ohio, 80%.[50]

- One Soviet trading corporation in New York averaged 350 applications a day from Americans seeking jobs in the Soviet Union.[56]

- Over one million families lost their farms between 1930 and 1934.[50]

- Corporate profits had dropped from $10 billion in 1929 to $1 billion in 1932.[50]

- Between 1929 and 1932, the income of the average American family was reduced by 40%.[57]

- Nine million savings accounts had been wiped out between 1930 and 1933.[50]

- 273,000 families had been evicted from their homes in 1932.[50]

- There were two million homeless people migrating around the country.[50]

- Over 60% of Americans were categorized as poor by the federal government in 1933.[50]

- In the last prosperous year (1929), there were 279,678 immigrants recorded, but in 1933 only 23,068 came to the U.S.[58][59]

- In the early 1930s, more people emigrated from the United States than immigrated to it.[60]

- With little economic activity there was scant demand for new coinage. No nickels or dimes were minted in 1932–33, no quarter dollars in 1931 or 1933, no half dollars from 1930 to 1932, and no silver dollars in the years 1929–33.

- The U.S. government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands, including some U.S. citizens, were deported against their will. Altogether about 400,000 Mexicans were repatriated.[61]

- New York social workers reported that 25% of all schoolchildren were malnourished. In the mining counties of West Virginia, Illinois, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania, the proportion of malnourished children was perhaps as high as 90%.[50]

- Many people became ill with diseases such as tuberculosis (TB).[50]

- The 1930 U.S. Census determined the U.S. population to be 122,775,046. About 40% of the population was under 20 years old.[62]

See also

- Entertainment during the Great Depression

- Penny auction (foreclosure)

- The New Deal and the arts in New Mexico

- Timeline of the Great Depression

- Ham and Eggs Movement, California pension plan, 1938–40

- Great Depression in Washington State Project

- Sales tax tokens

General:

References

- ↑ John Steele Gordon "10 Moments That Made American Business," American Heritage, February/March 2007.

- ↑ Radio was a growth industry, but far smaller than the automobile and electric power industries that were growth engines before 1929.

- ↑ Lester Chandler (1970).

- ↑ Chandler (1970); Jensen (1989); Mitchell (1964)

- ↑ The Migrant Experience. Memory.loc.gov (1998-04-06). Retrieved on 2013-07-14.

- ↑ American Exodus The Dust Bowl Mi. Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-14.

- ↑ Bordo, Goldin, and White , eds., The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (1998).

- ↑ , Robert Fuller, "Phantom of Fear" The Banking Panic of 1933 (2012) 241–42 fn. 45

- ↑ Hans Kaltenborn, It Seems Like Yesterday (1956) p. 88

- ↑ Richard J. Jensen, "The causes and cures of unemployment in the Great Depression." Journal of Interdisciplinary History (1989): 553-583 in JSTOR; online copy

- ↑ Janet Poppendieck, Breadlines knee-deep in wheat: Food assistance in the Great Depression (2014)

- ↑ Roger Biles, Big City Boss in Depression and War: Mayor Edward J. Kelly of Chicago (1984).

- ↑ Mason B. Williams, City of Ambition: FDR, LaGuardia, and the Making of Modern New York (2013)

- ↑ Richard Jensen, "The cities reelect Roosevelt: Ethnicity, religion, and class in 1940." Ethnicity. An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Study of Ethnic Relations (1981) 8#2: 189-195.

- ↑ Jon C. Teaford, The twentieth-century American city (1986) pp 90-96.

- ↑ Roger W. Lotchin, The Bad City in the Good War: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego (2003)

- ↑ John A. Garraty, The Great Depression (1986)

- ↑ Frank, Robert H.; Bernanke, Ben S. (2007). Principles of Macroeconomics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. p. 98.

- ↑ Willard W. Cochrane, Farm prices: myth and reality (U of Minnesota Press, 1958)

- ↑ League of Nations, World Economic Survey 1932–33 (1934) p. 43

- ↑ Broadus Mitchell, Depression Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929–1941 (1947),

- ↑ Garraty, Great Depression (1986) ch 1

- ↑ Robert Skidelsky, "The Great Depression: Keynes´s Perspective," in: Elisabeth Müller-Luckner, Harold James, The Interwar Depression in an International Context," (2002) p. 99

- ↑ Robert O. Paxton and Julie Hessler, Europe in the Twentieth Century (2011) ch 10–11

- ↑ "Index numbers of employment as reported by employers in leading cities, as of the first of each month, January 1935 to December 1936, with yearly averages since 1922.". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Index numbers of rates of wages for various classes of labour in Canada, 1913 to 1936". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Ralph Allen, Ordeal by Fire: Canada, 1910–1945 (1961), ch. 3, pp 37–39.

- ↑ "History, Economic—Labour Policy—1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ↑ Olivier Blanchard und Gerhard Illing, Makroökonomie, Pearson Studium, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7363-2, pp. 696–97

- ↑ Ellis Hawtley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly (1966)

- ↑ Mary Beth Norton, Carol Sheriff und David M. Katzman, A People and a Nation: A History of the United States, Volume II: Since 1865, Wadsworth Inc Fulfillment, 2011, ISBN 978-0-495-91590-4, p. 688

- ↑ Broadus Mitchell, Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929–1941 (1964)

- ↑ Parker, ed. Reflections on the Great Depression (2002)

- ↑ Specifically, when asked whether "as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression," 74% of respondents who taught or studied economic history disagreed, 21% agreed with provisos, and 6% fully agreed. Among respondents who taught or studied economic theory, 51% disagreed, 22% agreed with provisos, and 22% fully agreed. Robert Whaples, "Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), pp. 139–154 in JSTOR see also the summary at "EH.R: FORUM: The Great Depression". Eh.net. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ Kennedy, Freedom from Fear (1999)

- ↑ Kenneth D. Roose, The Economics of Recession and Revival: An Interpretation of 1937–38, (1969)

- ↑ The Federal Reserve doubled reserve requirements between August 1936 and May 1937

- ↑ Gene M. Gressley, "Thurman Arnold, Antitrust, and the New Deal," Business History Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 214–231 in JSTOR

- ↑ Kenneth D. Roose, "The Recession of 1937–38" Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jun., 1948) , pp. 239–248 in JSTOR

- ↑ Gary Dean Best, Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933–1938 (1990) pp 175–216

- ↑ Robert Higgs, "Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Mar., 1992), pp. 41–60

- ↑ Theodore Rosenof, Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1932–1993 (1997)

- ↑ Great Depression and World War Michael Lewis. The Library of Congress.

- ↑ Paul A. C. Koistinen, Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940–1945 (2004)

- ↑ Jensen (1989); Edwin E. Witte, "What The War Is Doing to Us". Review of Politics. (Jan. 1943). 5(1): 3–25 JSTOR 1404621

- ↑ Harold G. Vester. The U.S. Economy in World War III. (1988)

- 1 2 Smiley, Gene. Rethinking the Great Depression. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, publisher. 2002.

- 1 2 3 Hall, Thomas E., and Ferguson, David J. "The Great Depression: An International Disaster of Perverse Economic Policies". Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1998. pg 155

- ↑ "I remember the Wall Street Crash". BBC News. October 6, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Overproduction of Goods, Unequal Distribution of Wealth, High Unemployment, and Massive Poverty, From: President's Economic Council

- ↑ Q&A: Lessons from the Great Depression, By Barbara Kiviat, TIME, January 6, 2009

- ↑ About the Great Depression

- ↑ The Great Depression: The sequel, By Cameron Stacy, salon.com, April 2, 2008

- ↑ Economic Recovery in the Great Depression, Frank G. Steindl, Oklahoma State University

- ↑ Great Depression, The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

- ↑ A reign of rural terror, a world away, U.S. News, June 22, 2003

- ↑ American History – 1930–1939

- ↑ Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status in the United States of America, Source: US Department of Homeland Security

- ↑ The Facts Behind the Current Controversy Over Immigration, by Allan L. Damon, American Heritage Magazine, December 1981

- ↑ A Great Depression?, by Steve H. Hanke, Cato Institute

- ↑ The Great Depression and New Deal, by Joyce Bryant, Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

- ↑ 1931 U.S Census Report Contains 1930 Census results

Further reading

- Bernanke, Ben. Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton University Press, 2000) (Chapter One – "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression" online)

- Bernanke, Ben. "Money, Gold, and the Great Depression" – Speech given March 2, 2004;

- Best, Gary Dean. Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933–1938 (1991) ISBN 0-275-93524-8

- Best, Gary Dean. The Nickel and Dime Decade: American Popular Culture during the 1930s. (1993) online edition

- Bird, Caroline. The Invisible Scar (1966)

- Blumberg, Barbara. The New Deal and the Unemployed: The View from New York City (1977).

- Bordo, Michael D., Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White, eds., The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (1998). Advanced economic history.

- Bremer, William W. "Along the American Way: The New Deal's Work Relief Programs for the Unemployed." Journal of American History 62 (December 1975): 636–652 online in JSTOR

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds.; Public Opinion, 1935–1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls online edition

- Chandler, Lester. America's Greatest Depression (1970). overview by economic historian.

- Cravens, Hamilton. Great Depression: People and Perspectives (2009), social history excerpt and text search

- Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (2009) excerpt and text search

- Field, Alexander J. A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth (Yale University Press; 2011) 387 pages; argues that technological innovations in the 1930s laid the foundation for economic success in World War II and postwar

- Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963) ISBN 0-691-04147-4 classic monetarist explanation; highly statistical

- Fuller, Robert Lynn, "Phantom of Fear" The Banking Panic of 1933 (2012)

- Graham, John R.; Hazarika, Sonali & Narasimhan, Krishnamoorthy. "Financial Distress in the Great Depression" (2011) SSRN link to paper

- Grant, Michael Johnston. Down and Out on the Family Farm: Rural Rehabilitation in the Great Plains, 1929–1945 (2002)

- Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn. To Ask for an Equal Chance: African Americans in the Great Depression (2009) excerpt and text search

- Hapke, Laura. Daughters of the Great Depression: Women, Work, and Fiction in the American 1930s (1997)

- Higgs, Robert. Depression, War, and Cold War: Challenging the Myths of Conflict and Prosperity Oxford University Press for The Independent Institute, 2009.

- Higgs, Robert. "From Central Planning to the Market: The American Transformation, 1945–1947" Journal of Economic History, September 1999.

- Higgs, Robert. "Regime Uncertainty: Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed after the War" The Independent Review, Spring 1997.

- Higgs, Robert. "Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s" Journal of Economic History, March 1992.

- Himmelberg, Robert F. ed The Great Depression and the New Deal (2001), short overview

- Horwitz, Steven (2008). "Hoover's Economic Policies". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Howard, Donald S. The WPA and Federal Relief Policy (1943)

- Jensen, Richard J., "The Causes and Cures of Unemployment in the Great Depression", Journal of Interdisciplinary History (1989) 19(553–83) online in JSTOR

- Kehoe, Timothy J. and Edward C. Prescott. Great Depressions of the Twentieth Century' Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 2007.

- Kennedy, David. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (1999), wide-ranging survey by leading scholar; online edition

- Klein, Maury. Rainbow's End: The Crash of 1929 (2001) by economic historian

- Kubik, Paul J. "Federal Reserve Policy during the Great Depression: The Impact of Interwar Attitudes regarding Consumption and Consumer Credit" Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 30, 1996

- Leab, Daniel, ed. (2014). Encyclopedia of American Recessions and Depressions. ABC-CLIO 2 vol 919 pp. 2:527-80

- Lowitt, Richard and Beardsley Maurice, eds. One Third of a Nation: Lorena Hickock Reports on the Great Depression (1981)

- Lynd, Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd. Middletown in Transition. 1937. sociological study of Muncie, Indiana

- McElvaine Robert S. The Great Depression 2nd ed (1993) social history

- Milkis, Sidney M. and Jerome M. Mileur. The New Deal and the Triumph of Liberalism (2002) excerpt and text search

- Miller, Dorothy Laager "New York City in the Great Depression: Sheltering the Homeless", 2009 Arcadia Publishing

- Mitchell, Broadus. Depression Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929–1941 (1964), overview of economic history

- Parker, Randall E., ed. Reflections on the Great Depression (2002) interviews with 11 leading economists

- Rauchway, Eric. The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (2008) excerpt and text search

- Reed, Lawrence W. Great Myths of the Great Depression. Midland, MI: Mackinac Center (1981 & 2008), libertarian interpretation

- Romasco, Albert U. "Hoover-Roosevelt and the Great Depression: A Historiographic Inquiry into a Perennial Comparison." In John Braeman, Robert H. Bremner and David Brody, eds. The New Deal: The National Level (1973) v 1 pp. 3–26.

- Roose, Kenneth D. "The Recession of 1937–38" Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jun., 1948), pp. 239–248 in JSTOR

- Rose, Nancy. The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression (2009)

- Rosen, Elliot A. Roosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Economics of Recovery (2005) ISBN 0-8139-2368-9

- Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression (1963)

- Saloutos, Theodore. The American Farmer and the New Deal (1982)

- Singleton, Jeff. The American Dole: Unemployment Relief and the Welfare State in the Great Depression (2000)

- Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue: The Depression Decade (2008)

- Sitkoff, Harvard, ed. Fifty Years Later: The New Deal Evaluated (1985), liberal perspective

- Smiley, Gene. Rethinking the Great Depression (2002) ISBN 1-56663-472-5 economist blames Federal Reserve and gold standard

- Smith, Jason Scott. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956 (2005).

- Sternsher, Bernard ed., Hitting Home: The Great Depression in Town and Country (1970), readings on local history

- Szostak, Rick. Technological Innovation and the Great Depression (1995)

- Temin, Peter. Did Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression? (1976)

- Terkel, Studs. Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

- Tindall, George B. The Emergence of the New South, 1915–1945 (1967). History of entire region by leading scholar

- Trout, Charles H. Boston, the Great Depression, and the New Deal (1977)

- Uys, Errol Lincoln. Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression (Routledge, 2003) ISBN 0-415-94575-5 author's site

- Warren, Harris Gaylord. Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression (1959).

- Watkins, T. H. The Great Depression: America in the 1930s. (2009). dexcerpt and text search

- Wecter, Dixon. The Age of the Great Depression, 1929–1941 (1948)

- Wicker, Elmus. The Banking Panics of the Great Depression 1996 online review

- White, Eugene N. "The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited". The Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 67–83, evaluates different theories in JSTOR

- Wheeler, Mark ed. The Economics of the Great Depression (1998)

- Young, William H., and Nancy K. Young. The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia (2 vol. 2007)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Depression in the United States. |

- essays and lesson plans

- Rare Color Photos from the Great Depression – slideshow by The Huffington Post

- A collection of Great Depression documents on FRASER

- The Great Depression in Washington State, a multimedia collection of photographs, maps, digitized newspaper articles and essays on the impact of the Depression. Includes sections on public works, theater arts, hoovervilles and radicalism.

.svg.png)