Fritz Leiber

| Fritz Leiber | |

|---|---|

Leiber portrait by Ed Emshwiller (July 1969) | |

| Born |

Fritz Reuter Leiber, Jr. December 24, 1910 Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Died |

September 5, 1992 (aged 81) San Francisco, California, United States |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1934–1992[lower-alpha 1] |

| Genre | Fantasy, horror, science fiction |

| Notable works | Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser |

| Relatives |

Fritz Leiber (father) Virginia Bronson Leiber (mother) |

Fritz Reuter Leiber, Jr. (December 24, 1910 – September 5, 1992) was an American writer of fantasy, horror, and science fiction. He was also a poet, actor in theater and films, playwright and chess expert.[lower-alpha 2] With writers such as Robert E. Howard and Michael Moorcock, Leiber can be regarded as one of the fathers of sword and sorcery fantasy, having in fact created the term. Moreover, he excelled in all fields of speculative fiction, writing award-winning work in fantasy, horror, and science fiction.

Life

Fritz Leiber was born December 24, 1910, in Chicago, Illinois, to the actors Fritz Leiber and Virginia Bronson Leiber. For a time, he seemed inclined to follow in his parents' footsteps; the theater and actors are prominently featured in his fiction. He spent 1928 touring with his parents' Shakespeare company (Fritz Leiber & Co.) before entering the University of Chicago, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and received an undergraduate Ph.B. degree in psychology and physiology[2] or biology[3] with honors in 1932. From 1932 to 1933, he worked as a lay reader and studied as a candidate for the ministry at the Episcopal Church-affiliated General Theological Seminary in Chelsea, Manhattan without taking a degree.

After pursuing graduate studies in philosophy at the University of Chicago from 1933 to 1934 and failing once more to take a degree, he remained based in Chicago while touring intermittently with his parents' company (under the stage name of "Francis Lathrop") and pursuing a concurrent literary career; six short stories in the 2010 collection Strange Wonders: A Collection of Rare Fritz Leiber Works carry 1934 and 1935 dates.[lower-alpha 1]. He also appeared alongside his father in uncredited parts in several films, including George Cukor's Camille (1936), James Whale's The Great Garrick (1937) and William Dieterle's The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939).

In 1936, he initiated a brief yet intense correspondence with H.P. Lovecraft, who "encouraged and influenced [Leiber's] literary development" before succumbing to small intestine cancer and malnutrition in March 1937.[5] He introduced Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in "Two Sought Adventure," his first professionally-published short story in the August 1939 edition of the John W. Campbell-edited Unknown.[6][7]

Leiber married Jonquil Stephens on January 16, 1936; their only child, the philosopher and science fiction writer Justin Leiber, was born in 1938. From 1937 to 1941, he was employed by Consolidated Book Publishing as a staff writer for the Standard American Encyclopedia. In 1941, the family moved to California, where Leiber served as a speech and drama instructor at Occidental College during the 1941-1942 academic year.

Unable to conceal his disdain for academic politics as the United States entered World War II, he decided that the struggle against fascism was more important than his long-held pacifist convictions. He accepted a position with Douglas Aircraft in quality inspection, primarily working on the C-47 Skytrain; throughout the war, he continued to regularly publish fiction in a variety of periodicals.[7]

Thereafter, the family returned to Chicago, where Leiber served as associate editor of Science Digest from 1945 to 1956. During this decade (forestalled by a fallow interregnum from 1954 to 1956), his output (including the 1947 Arkham House anthology Night's Black Agents) was characterized by Poul Anderson as "a lot of the best science fiction and fantasy in the business." In 1958, the Leibers returned to Los Angeles. By this juncture, he was able to relinquish his journalistic career and support his family as a full-time fiction writer.[7]

Jonquil's death in 1969 precipitated Leiber's permanent relocation to San Francisco and exacerbated his longstanding alcohol use disorder after twelve years of fellowship in Alcoholics Anonymous; however, he would gradually regain relative sobriety (an effort impeded by comorbid barbiturate abuse) over the next two decades.[8] In 1977, he returned to his original form with a fantasy novel set in modern-day San Francisco, Our Lady of Darkness, which is about a writer of weird tales who must deal with the death of his wife and his recovery from alcoholism.

Perhaps as a result of his substance abuse, Leiber seems to have suffered periods of penury in the 1970s; Harlan Ellison has written of his anger at finding that the much-awarded Leiber had to write his novels on a manual typewriter that was propped up over the sink in his apartment, and Marc Laidlaw wrote that, when visiting Leiber as a fan in 1976, he "was shocked to find him occupying one small room of a seedy San Francisco residence hotel, its squalor relieved mainly by walls of books".[9] Other reports suggest that Leiber preferred to live simply in the city, spending his money on dining, movies and travel. In the last years of his life, royalty checks from TSR, Inc. (the makers of Dungeons and Dragons, who had licensed the mythos of the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser series) were enough in themselves to ensure that he lived comfortably.[10]

In 1992, the last year of his life, Leiber married his second wife, Margo Skinner, a journalist and poet with whom he had been friends for many years.

Leiber's death occurred a few weeks after a physical collapse while traveling from a science fiction convention in London, Ontario, with Skinner. The cause of his death was given as "organic brain disease".

He wrote a 100-page-plus memoir, Not Much Disorder and Not So Early Sex, which can be found in The Ghost Light (1984).[11]

Leiber's own literary criticism, including several essays on Lovecraft, was collected in the volume Fafhrd and Me (1990).[12]

Theater

As the child of two Shakespearean actors—Fritz, Sr. and Virginia (née Bronson)—Leiber was fascinated with the stage, describing itinerant Shakespearean companies in stories like "No Great Magic" and "Four Ghosts in Hamlet," and creating an actor/producer protagonist for his novel A Specter is Haunting Texas.

Although his Change War novel, The Big Time, is about a war between two factions, the "Snakes" and the "Spiders", changing and rechanging history throughout the universe, all the action takes place in a small bubble of isolated space-time about the size of a theatrical stage, with only a handful of characters. Judith Merril (in the July 1969 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction) remarks on Leiber's acting skills when the writer won a science fiction convention costume ball. Leiber's costume consisted of a cardboard military collar over turned-up jacket lapels, cardboard insignia, an armband, and a spider pencilled large in black on his forehead, thus turning him into an officer of the Spiders, one of the combatants in his Change War stories. "The only other component," Merril writes, "was the Leiber instinct for theatre."

Films

Due to the similarity of the names of the father and the son, some filmographies incorrectly attribute to Fritz, Jr. roles which were in fact played by his father, Fritz Leiber, Sr. Fritz, Sr. was the evil Inquisitor in the Errol Flynn adventure film The Sea Hawk (1940) and had played in many other movies from 1917 onwards until the late 1950s. It is to be noted that it is the elder Leiber, not the younger, who appears in the Vincent Price vehicle The Web (1947) and in Charlie Chaplin's Monsieur Verdoux (1947).

In the cult horror film Equinox (1970) directed by Dennis Muren and Jack Woods, Leiber has a cameo appearance as Dr. Watermann, a geologist. In the edited second version of the movie Leiber has no spoken dialogue in the film but features in a few scenes. The original version of the movie has a longer appearance by Leiber recounting the ancient book and a brief speaking role, all of which was cut from the re-release of the film.

He also appears in the 1979 Schick Sunn Classics documentary The Bermuda Triangle, based on the book by Charles Berlitz, as Chavez.

Writing career

Leiber was heavily influenced by H. P. Lovecraft and Robert Graves in the first two decades of his career. Beginning in the late 1950s, he was increasingly influenced by the works of Carl Jung, particularly by the concepts of the anima and the shadow. From the mid-1960s onwards, he began incorporating elements of Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces. These concepts are often openly mentioned in his stories, especially the anima, which becomes a method of exploring his fascination with, but estrangement from, the female.

Leiber liked cats, which feature prominently in many of his stories. Tigerishka, for example, is a cat-like alien who is sexually attractive to the human protagonist yet repelled by human customs in the novel The Wanderer. Leiber's "Gummitch" stories feature a kitten with an I.Q. of 160, just waiting for his ritual cup of coffee so that he can become human, too.

His first stories were inspired by the Cthulhu Mythos. Leiber later wrote several essays on Lovecraft such as "A Literary Copernicus" which formed key moments in the serious critical appreciation of Lovecraft's life and work.

Leiber's first professional sale was Two Sought Adventure (Unknown, August 1939),[13] which introduced his most famous characters, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. In 1943, his first two novels were serialized in Unknown (the supernatural horror-oriented Conjure Wife, partially inspired by his deleterious experiences on the faculty of Occidental College) and Astounding Science Fiction (Gather, Darkness).

1947 marked the publication of his first book, Night's Black Agents, a short story collection containing seven stories grouped as 'Modern Horrors', one as a 'Transition', and two grouped as 'Ancient Adventures': "The Sunken Land" and "Adept's Gambit", which are both stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

Book publication of the science fiction novel Gather, Darkness followed in 1950. It deals with a futuristic world that follows the Second Atomic Age which is ruled by scientists, until in the throes of a new Dark Age, the witches revolt.

In 1951, Leiber was Guest of Honor at the World Science Fiction Convention in New Orleans. Further novels followed during the 1950s, and in 1958 The Big Time won the Hugo Award for Best Novel.[14]

Leiber published many further books in the 1960s. His novel The Wanderer (1964) also received the Hugo for Best Novel.[14] In the novel, an artificial planet, quickly nicknamed the Wanderer, materializes from hyperspace within earth's orbit. The Wanderer's gravitational field captures the moon and shatters it into something like one of Saturn's rings. On earth, the Wanderer's gravity well triggers massive earthquakes, tsunamis, and tidal phenomena. The multi-threaded plot follows the exploits of a large ensemble cast as they struggle to survive the global disaster.

Leiber received the Hugo Award for Best Novella in 1970 and 1971 for "Ship of Shadows" (1969) and "Ill Met in Lankhmar" (1970). "Gonna Roll the Bones" (1967), his contribution to Harlan Ellison's Dangerous Visions anthology, received the Hugo Award for Best Novelette and the Nebula Award for Best Novelette in 1968.[14]

Our Lady of Darkness (1977)—originally serialized in short form in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction under the title "The Pale Brown Thing" (1977)—featured cities as the breeding grounds for new types of elementals called paramentals, summonable by the dark art of megapolisomancy, with such activities centering on the Transamerica Pyramid. Its main characters include Franz Westen, Jaime Donaldus Byers, and the magician Thibault de Castries. Our Lady of Darkness won the World Fantasy Award—Novel.[14]

Leiber also did the 1966 novelization of the Clair Huffaker screenplay of Tarzan and the Valley of Gold.[15]

Many of Leiber's most-acclaimed works are short stories, especially in the horror genre. Owing to such stories as "The Smoke Ghost," "The Girl With the Hungry Eyes" and "You're All Alone" (a.k.a. "The Sinful Ones"), he is widely regarded as one of the forerunners of the modern urban horror story. (Ramsey Campbell cites him as his single biggest influence.) Leiber also challenged the conventions of science fiction through reflexive narratives such as "A Bad Day For Sales" (first published in Galaxy Science Fiction, July 1953), in which the protagonist, Robie, "America’s only genuine mobile salesrobot,"[16] references the title character of Isaac Asimov’s idealistic robot story, "Robbie."[17] Questioning Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, Leiber imagines the futility of automatons in a post-apocalyptic New York City. In his later years, Leiber returned to short story horror in such works as "Horrible Imaginings", "Black Has Its Charms" and the award-winning "The Button Moulder."[18]

The short parallel worlds story "Catch That Zeppelin!" (1975) received the Hugo Award for Best Short Story and the Nebula Award for Best Short Story in 1976.[14] This story shows a plausible alternate reality that is much better than our own, whereas the typical parallel universe story depicts a world that is much worse than our own. "Belsen Express" (1975) won the World Fantasy Award—Short Fiction. Both stories reflect Leiber's uneasy fascination with Nazism—an uneasiness compounded by his mixed feelings about his German ancestry and his philosophical pacifism during World War II.

Leiber was named the second Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy by participants in the 1975 World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon), after the posthumous inaugural award to J. R. R. Tolkien.[14] Next year he won the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement.[14] He was Guest of Honor at the 1979 Worldcon in Brighton, England (1979). The Science Fiction Writers of America made him its fifth SFWA Grand Master in 1981;[19] the Horror Writers Association made him an inaugural winner of the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1988 (named in 1987);[20] and the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in 2001, its sixth class of two deceased and two living writers.[21]

Leiber was a founding member of the Swordsmen and Sorcerers' Guild of America, a loose-knit group of Heroic fantasy authors founded in the 1960s, led by Lin Carter, with entry by fantasy credentials alone. Some works by SAGA members were published in Lin Carter's Flashing Swords! anthologies. Leiber himself is credited with inventing the term sword and sorcery for the particular subgenre of epic fantasy exemplified by his Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories.

In an appreciation in the July 1969 "Special Fritz Leiber Issue" of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Judith Merril writes of Leiber's connection with his readers: "That this kind of personal response...is shared by thousands of other readers, has been made clear on several occasions." The November 1959 issue of Fantastic, for instance: Leiber had just come out of one of his recurrent dry spells, and editor Cele Lalli bought up all his new material until there was enough [five stories] to fill an issue; the magazine came out with a big black headline across its cover — Leiber Is Back!

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser

His legacy appears to have been consolidated by the most famous of his creations, the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories, written over a span of 50 years.[6] The first of them, "Two Sought Adventure", appeared in Unknown, August 1939. They are concerned with an unlikely pair of heroes found in and around the city of Lankhmar. Fafhrd was based on Leiber himself and the Mouser on his friend Harry Otto Fischer, and the two characters were created in a series of letters exchanged by the two in the mid-1930s. These stories were among the progenitors of many of the tropes of the sword and sorcery genre. They are also notable among sword and sorcery stories in that, over the course of the stories, his two heroes mature, take on more responsibilities, and eventually settle down into marriage.

Some Fafhrd and Mouser stories were recognized by annual genre awards: "Scylla's Daughter" (1961) was "Short Story" Hugo finalist and "Ill Met in Lankhmar" (1970) won the "Best Novella" Hugo and Nebula Awards.[14] Fittingly, Leiber's last major work, "The Knight and Knave of Swords" (1991) brought the series to a satisfactory close while leaving room for possible sequels. In the last year of his life, Leiber was considering allowing the series to be continued by other writers, but his sudden death made this more difficult. One new Fafhrd and the Mouser novel, Swords Against the Shadowland, by Robin Wayne Bailey, did appear in 1998, and according to the author's web site, a second volume is in the works.

The stories were influential in shaping the genre and were influential on other works. Joanna Russ' stories about thief-assassin Alyx (collected in 1976 in The Adventures of Alyx) were in part inspired by Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, and Alyx in fact made guest appearances in two of Leiber's stories. Numerous writers have paid homage to the stories. For instance, Terry Pratchett's city of Ankh-Morpork bears something more than a passing resemblance to Lankhmar (acknowledged by Pratchett by the placing of the swordsman-thief "The Weasel" and his giant barbarian comrade "Bravd" in the opening scenes of the first Discworld novel). More recently, playing off the visit of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser to our world in Adept's Gambit (set in second century B.C. Tyre), Steven Saylor's short story "Ill Seen in Tyre" takes his Roma Sub Rosa series hero Gordianus to the city of Tyre a hundred years later, where the two visitors from Nehwon are remembered as local legends.[22]

Fischer and Leiber contributed to the original game design of the wargame Lankhmar—published in 1976 by TSR.[23]

Selected works

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series

- Two Sought Adventure (1958). Collection of six short stories. Later expanded and retitled as Swords Against Death.

- Swords and Deviltry (1970). Collection of 3 short stories.

- Swords Against Death (1970). Collection of 10 short stories; an expanded edition of Two Sought Adventure

- Swords in the Mist (1968). Collection of 6 short stories.

- Swords Against Wizardry (1968). Collection of 4 short stories.

- The Swords of Lankhmar (1968). Expanded from "Scylla's Daughter" in Fantastic, 1963.

- Swords and Ice Magic (1977). Collection of 8 short stories. (Though see Rime Isle below.)

- The Knight and Knave of Swords (1988). Collection of 4 short stories. Retitled Farewell to Lankhmar (2000, UK).

Novels/Novellas

- Conjure Wife (originally appeared in Unknown Worlds, April 1943) — This novel relates a college professor's discovery that his wife (and many other women) are regularly using magic against and for one another and their husbands.

- Gather, Darkness! (serialized in Astounding, May, June, and July 1943) – a dystopian and rather satirical depiction of a future theocracy and the revolution which brings it down.

- Destiny Times Three (1945, first in Astounding) (reprinted 1957 as Galaxy Novel number 28)

- The Sinful Ones (1953), an adulterated version of You're All Alone (1950 Fantastic Adventures abridged); Leiber rewrote the inserted passages and saw published a revised edition in 1980.

- The Green Millennium (1953)

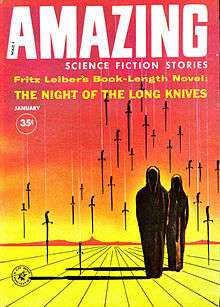

- The Night of the Long Knives (Amazing Science Fiction Stories, January 1960)

- The Big Time (expanded 1961 from a version serialized in Galaxy, March and April 1958, which won a Hugo) — Change War series. Also available in Ship of Shadows (1979) – see Collections below.

- The Silver Eggheads (1961; a shorter version was published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1959)

- The Wanderer (1964)

- Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966) (novelisation of a Clair Huffaker screenplay)

- A Spectre is Haunting Texas (1969)

- You're All Alone (1972) (the first book edition includes two shorter works as well, a revised version was issued as The Sinful Ones)

- Our Lady of Darkness (1977) This novel, the title of which is drawn from Thomas de Quincey's Suspiria de Profundis, was published the same year as Dario Argento's Suspiria which referenced the same idea in de Quincey. It also makes fictional reference to fellow novelists Jack London, Clark Ashton Smith and H.P. Lovecraft and others.

- Rime Isle (1977) (somewhere between a novella and a two-novelette collection, composed of "The Frost Monstreme" and "Rime Isle" offered as a unitary volume)

- Ervool (Cheap Street, 1980—limited ed of 200 numbered copies). A standalone edition of a short story originally published in the 1940s fanzine The Acolyte.

- The Dealings of Daniel Kesserich (1997) — H. P. Lovecraftian novella written in 1936 and lost for decades

- Dark Ladies (NY: Tor Books, 1999). Omnibus edition of Conjure Wife and Our Lady of Darkness

Collections

- Night's Black Agents (Arkham House, 1947). Reprinted by Berkley, 1978 with the addition of two stories – "The Girl With the Hungry Eyes" and "A Bit of the Dark World". The definitive hardcover edition is the Gregg Press (1980) edition, which adds a Foreword by Richard Powers to the complete contents of the Berkley edition.

- The Mind Spider and Other Stories (1961). Collection of 6 short stories.

- Shadows With Eyes (1962). Collection of 6 short stories.

- A Pail of Air (1964). Collection of 11 short stories.

- Ships to the Stars (1964). Collection of 6 short stories.

- The Night of the Wolf (1966). Collection of 4 short stories.

- The Secret Songs (1968). Collection of 11 short stories.

- Night Monsters (1969). Collection of 4 short stories. UK (1974) edition drops 1 story and adds 4.

- The Best of Fritz Leiber (1974). Collection of 22 short stories. (Introduction by Poul Anderson, "The Wizard of Nehwon")

- The Book of Fritz Leiber (1974). Collection of 10 stories and 9 articles.

- The Second Book of Fritz Leiber (1975). Collection of 4 stories, 1 play, and 6 articles.

- Bazaar of the Bizarre (1978)

- Heroes and Horrors (1978). Collection of 9 stories.

- Ship of Shadows (1979). Collection of 5 award winning short stories [ 3 stories 2 novellas & 1 novelThe BigTime.] [24]

- Changewar (1983). Collection of the Changewar short stories (7 stories).

- The Ghost Light (1984). Collection of 9 stories with illustrations and an autobiographic essay with photographs.

- The Leiber Chronicles (1990) Collection of 44 short stories.

- Gummitch and Friends (1992). Leiber's cat stories, the first five of which feature Gummitch.

- Ill Met in Lankhmar (White Wolf Publishing, 1995, ISBN 1-56504-926-8) combines Swords and Deviltry (1970) and Swords Against Death (1970).

- Lean Times in Lankhmar (White Wolf Publishing, 1996, ISBN 1-56504-927-6) combines Swords in the Mist (1970) and Swords Against Wizardry (1970)

- Return to Lankhmar (White Wolf Publishing, 1997, ISBN 1-56504-928-4) combines The Swords of Lankhmar (1968) and Swords and Ice Magic (1977)

- Farewell to Lankhmar (White Wolf Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1-56504-897-0)

- The Black Gondolier (2000) Collection of 18 short stories.

- Smoke Ghost and Other Apparitions (2002) Collection of 18 short stories.

- Day Dark, Night Bright (2002) Collection of 20 short stories.

- Horrible Imaginings (2004) Collection of 15 short stories.

- Strange Wonders (Subterranean Press, 2010). Edited by Benjamin Szumskyj. Collection of 48 unpublished and uncollected works (drafts, fragments, poems, essays, and a play).

- Fritz Leiber: Selected Stories (Night Shade Books, 2010). Edited by Jonathan Strahan and Charles N. Brown. Collection of 17 stories, with an introduction by Neil Gaiman.

Plays

- Quicks Around the Zodiac: A Farce. (Newcastle, VA: Cheap Street, 1983). (Reprinted in Strange Wonders, 2010).

Essays

- The Mystery of the Japanese Clock. A standalone essay on the workings of a digital Japanese clock. Montgolfier Press, 1982, with Introduction by his son Justin Leiber. (Reprinted in Strange Wonders, 2010).

Poetry

- Demons of the Upper Air (Glendale, CA: Roy A. Squires, 1969).

- Sonnets to Jonquil and All (Glendale, CA: Roy A. Squires, 1978).

Screen adaptations

Conjure Wife has been made into feature films three times under other titles:

- Weird Woman (1944) starring Lon Chaney, Jr.. One of six Inner Sanctum mystery films made by Universal Studios based upon the old Inner Sanctum radio series.

- Conjure Wife was also adapted for the 1960 TV series Moment of Fear (episode title "The Accomplice")

- Night of the Eagle (a.k.a. Burn, Witch, Burn!) (1962) (screenplay by Charles Beaumont, Richard Matheson and George Baxt, directed by Sidney Hayers, produced by Albert Fennell)

- Witches' Brew (a.k.a. Which Witch is Which?) (1980) Directed by Richard Shore and starring Teri Garr and Richard Benjamin.

A new film adaptation of Conjure Wife was announced in 2008, to be filmed by US director Billy Ray. It is slated to be a United Artists/Studio Canal co-production.[25]

"The Girl With the Hungry Eyes" was filmed under that title by Kastenbaum Films in 1995. The Girl with the Hungry Eyes. Director: Jon Jacobs; Writers:Christina Fulton (additional story and dialogue), Jon Jacobs; Stars:Christina Fulton, Isaac Turner and Leon Herbert. (This film is not to be confused with the 1967 William Rotsler film The Girl with the Hungry Eyes which is entirely unrelated to Leiber's story).

Two Leiber stories were filmed for TV for Rod Serling's Night Gallery. These were "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" (1970) (adapted by Robert M. Young and directed by John Badham); and "The Dead Man" (adapted and directed by Douglas Heyes).

Quotations

Consider the age in which we live. It wants magicians…. A scientist tells people the truth. When times are good—that is, when the truth offers no threat—people don't mind.… A magician, on the other hand, tells people what they wish were true—that perpetual motion works, that cancer can be cured by colored lights, that a psychosis is no worse than a head cold, that they'll live forever. In good times magicians are laughed at. They're a luxury of the spoiled wealthy few. But in bad times people sell their souls for magic cures and buy perpetual-motion machines to power their war rockets.

- —"Poor Superman" 1951[26]

Everyone knows Newton as the great scientist. Few remember that he spent half his life muddling with alchemy, looking for the philosopher's stone. That was the pebble by the seashore he really wanted to find.

- —"Poor Superman" 1951[27]

If you could sum up all you felt about life and crystallize it in one master insight, you would have said it all and you would be dead.[28]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ The Web Novice. "California Chess Reminiscences". Chessdryad.com. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- ↑ http://archon.lib.uh.edu/?p=collections/findingaid&id=281&q=

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=vl6gLmUNFRYC&pg=PA18&dq=fritz+leiber+biological+sciences&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjCm436qMPQAhXFQyYKHdumAqIQ6AEIHTAA#v=onepage&q=fritz%20leiber%20biological%20sciences&f=false

- ↑ "Fritz Leiber – Summary Bibliography". ISFDB. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ↑ http://sciencefiction.loa.org/biographies/leiber.php

- 1 2 Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 2013-04-04. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Poul (1974), "The Wizard of Nehwon", The Best of Fritz Leiber, NY: Doubleday, pp. vii–xv.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=gsToCwAAQBAJ&pg=PR6&dq=fritz+leiber+occidental&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj2--PliMPQAhVDYiYKHYbPCNEQ6AEIPDAG#v=onepage&q=science%20digest&f=false

- ↑ Laidlaw, Marc, "On Our Lady of Darkness," in the anthology Horror: Another 100 Best Books, edited by Stephen Jones and Kim Newman, Carroll & Graf, 2005.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=gsToCwAAQBAJ&pg=PR7&dq=fritz+leiber+royalties&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjY9qj4nMPQAhWLLSYKHRpfDk8Q6AEIOzAG#v=onepage&q=fritz%20leiber%20royalties&f=false

- ↑ Leiber, Fritz (1984). The Ghost Light. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-06812-0.

- ↑ Leiber, Fritz (1990). Fafhrd and Me. Newark NJ: Wildside Press.

- ↑ Ellison, Harlan (1967). Dangerous Visions - Introduction to: Gonna Roll the Bones. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-425-06176-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Leiber, Fritz". The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index to Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ Bill and Sue-On Hillman. "ERBzine 0210: Tarzan and the Valley of Gold ~ ERB C.H.A.S.E.R". Erbzine.com. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- ↑ Leiber, Fritz. "A Bad Day For Sales." Sense of Wonder: A Century of Science Fiction. Ed. 1. Leigh Ronald Grossman. Wildside Press, 2011. 422. Print.

- ↑ Grossman, Leigh R. Ed. Sense of Wonder: A Century of Science Fiction. 1. Wildside Press, 2011. 421. Print.

- ↑ Ramsey Campbell

- ↑ "Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ "Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement". Horror Writers Association (HWA). Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved 2013-04-01. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ↑ Saylor, Steven, "Ill Seen in Tyre," in the anthology Rogues, edited by Gardner Dozois and George R.R. Martin, Bantam, 2014.

- ↑ Shannon Appelcline (2011). Designers & Dragons. Mongoose Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-907702-58-7.

- ↑ Victor Gollancz [publisher] Dust Jacket bio.

- ↑ "Billy Ray to write, direct 'Conjure Wife'", UPI (upi.com), December 19, 2008. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ Heinlein, Robert A., ed. (1952), Tomorrow, the Stars, NY: Doubleday, SBN 425-01426-6, p. 207.

- ↑ Heinlein, ed., p. 208.

- ↑ Adair, Gerald. "Illuminating the Ghost Light: Final Acts in the Theater of Fritz Leiber" (PDF). Jstor. International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

Further reading

Works about Fritz Leiber

- Magazine issues devoted to Fritz Leiber

- Fantastic, November 1959

- The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1969

- The Silver Eel (1978). edited by Robert P. Barker.

- Fantasy Commentator double issue No 57/58 (2004). Edited by Benjamin J. Szumskyj for publisher A. Langley Searles. Contains a wealth of critical essays on Leiber's work, together with three poems by Leiber: "Challenge", "Ghosts" and "The Grey Mouser".

- A bibliography of Leiber's work is Fritz Leiber: A Bibliography 1934–1979 by Chris Morgan (Birmingham, UK: Morgenstern, 1979). It is fairly definitive as to the date of publication but Leiber's work badly needs an updated comprehensive bibliography.

- Jeff Frane. Fritz Leiber (Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House/Borgo Press, 1980) was the first full-length monograph on Leiber's life and literary work.

- Tom Staicar. Fritz Leiber(NY: Fredrick Ungar Publishing Co, 1983).

- Bruce Byfield. Byfield, Bruce (1991). Witches of the Mind: A Critical Study of Fritz Leiber. West Warwick: Necronomicon Press. ISBN 0-940884-35-6.

- Benjamin J. Szumskyj (ed) Fritz Leiber: Critical Essays. (2007)

- John Howard. "In Smoke and Soot I Will Worship: The Ghost Stories of Fritz Leiber". All Hallows 4 (1993); Fantasy Commentator 57/58 (2004); in Howard's Touchstones: Essays on the Fantastic. Staffordshire UK: Alchemy Press, 2014.

- John Howard. "The Addition of Secondary Narratives". Fantasy Commentator 57/58 (2004); expanded as "Storytelling wonder-questing, mortal me: The transformation of 'The Pale Brown Thing' into Our Lady of Darkness in Szumskyj (2007); in Howard's Touchstones: Essays on the Fantastic. Staffordshire UK: Alchemy Press, 2014.

- An essay examining Leiber's literary relationship with H. P. Lovecraft ("Passing the Torch: H.P. Lovecraft and Fritz Leiber") appears in S. T. Joshi's The Evolution of the Weird Tale (2004).Joshi, S (2004). The Evolution of the Weird Tale. New York: Hippocampus Press. pp. 124–35. ISBN 978-0-9748789-2-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fritz Leiber. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fritz Leiber |

- "Fritz Leiber biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Fritz Leiber at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Fritz Leiber at Goodreads

- Fritz Leiber at the Internet Movie Database

- Fritz Leiber at the Internet Book List

- Works by Fritz Leiber at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Fritz Leiber at Internet Archive

- Works by Fritz Leiber at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lankhmar The Fritz Leiber Home Page