Joris Hoefnagel

Joris Hoefnagel or Georg Hoefnagel (1542, in Antwerp – 24 July 1601, in Vienna) was a Flemish painter, printmaker, miniaturist, draftsman and merchant. He is noted for his illustrations of natural history subjects, topographical views, illuminations and mythological works. He was one of the last manuscript illuminators and made a major contribution to the development of topographical drawing.

His manuscript illuminations and ornamental designs played an important role in the emergence of floral still-life painting as an independent genre in northern Europe at the end of the 16th century. The almost scientific naturalism of his botanical and animal drawings served as a model for a later generation of Netherlandish artists.[1]

Life

Early years

Joris Hoefnagel was the son of Jacob Hoefnagel, a dealer in diamonds and luxury goods such as tapestries, and his wife Elisabeth Vezelaer, daughter of the Antwerp mint master Joris Vezelaer. As his father likely wished him to enter the family business, he received a comprehensive humanistic education. He spoke, in addition to his native Dutch, several languages and was able to write poetry and play various musical instruments. In one of his works, Hoefnagel described himself as self-taught as an artist. However, according to the early Flemish biographer Karel van Mander he received his first art lessons from Hans Bol, probably while he was still in Antwerp (1570-1576). This apprenticeship with Hans Bol is not documented.[2]

Travels

He lived from 1560 to 1562 in France, where he attended the universities of Bourges and Orléans. Here he probably made his first landscape drawings. He was forced to leave France in 1563 due to religious unrest and he returned to Antwerp. He left soon thereafter for Spain, where he resided from 1563 to 1567 and was active on behalf of the family business. He made various sketches of places in Spain and was particularly fascinated with Seville, the primary colonial trading port of Spain, where he could see many exotic animals and plants. He returned to Antwerp in 1567 but may have visited his hometown in between on business. He travelled to England in 1568 and resided in London for a few months where he built friendships with other Flemish businessmen.[2] After returning to Antwerp in 1569, Joris Hoefnagel married Suzanne van Onchem in 1571 and in 1573 the couple had a son called Jacob, who would also become an artist.[3]

Exile

After the Sack of Antwerp by Spanish troops during the Eighty Years War in 1576, in which much of the family fortune was lost to plunder, Joris Hoefnagel left his hometown. He traveled in 1577, accompanied by the cartographer Abraham Ortelius, along the Rhine via Frankfurt, Augsburg and Munich to Venice and Rome. The pair also travelled southwards from Rome to Naples and visited various ancient sites.[2]

The art patron Hans Fugger and the physician Adolf Occo, whom he met in Augsburg, recommended him to the Duke of Bavaria, Albert V. The Duke was impressed by Hoefnagel’s miniatures and promised him a job as a court painter. In Rome he was introduced to the circle of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. Thanks to his special ability in miniature painting he was offered by the Cardinal in 1578 the position of the late miniaturist Giulio Clovio. He decided, however, to take on the position at the ducal court in Munich. He lived in Munich for about eight years and worked at the court of the Bavarian dukes Albert V and William V. Hoefnagel was granted the freedom to pursue his own interests and seems to have accepted the post at the ducal court mainly not to be hemmed in by the city and guild rules. He also took on commissions from Fugger and the Este family of Ferrara. In between he worked in Innsbruck at the court of Archduke Ferdinand II. He also continued with his trading activities.[2]

As a Calvinist, he was forced to leave Munich in 1591 when a rule was imposed that all members of the court had to proclaim their adherence to the Catholic faith. He then went to work for Emperor Rudolf II, first residing in the city of Frankfurt am Main, where he moved in a circle of Flemish humanists, merchants, artists and publishers. In particular his friendship with the Flemish botanist Carolus Clusius may have played an important role in his later botanical illustrations. In 1594, he was forced to leave Frankfurt because of the repression of the Calvinist faith. He worked in his final years in Vienna but made regular visits to Prague. His brother Daniel lived in Vienna, where he ran a business under court protection. At this time Joris Hoefnagel promoted his son Jacob at court. He regularly collaborated with his son on artistic projects. According to Karel van Mander he died in Vienna in 1600 but this is not certain as there continue to be references to him in documents referring to his brother Daniel and his son Jacob after that date.[2]

Works

Hoefnagel was a very versatile artist and is known for his landscapes, emblems, miniatures, topographical drawings and genre and mythological paintings. Part of Hoefnagel's artistic works was kept in the Dutch Republic by Constantijn Huygens when bequeathed to the Huygens family at Hoefnagel's death. These works were seen by Dutch artists and exercised an important influence on the development of Dutch still life and naturalist art.[4]

Landscapes and topographical works

%2C_Braun_%26_Hoefnagel%2C_1565.jpg)

During his trip to England, he made drawings of royal palaces such as Windsor Castle and Nonsuch Palace, which are regarded as some of the earliest realist landscape watercolours in England.[2]

Hoefnagels made many landscape drawings during his travels in Europe. These later served as the models for engravings for Ortelius' Theatrum orbis terrarum (1570) and Braun's Civitates orbis terrarum (Cologne, 1572–1618). The Civitates orbis terrarum was with its six volumes the most extensive atlas of its time. Hoefnagel worked intermittently on the Civitates his whole life and may have acted as an agent for the project, by commissioning views from other artists. He also completed more than 60 illustrations himself, including various views in Bavaria, Italy and Bohemia. He enlivened the finished engravings with a Mannerist sense of fantasy and wit by using dramatic perspectives and ornamental cartouches. Due to the topographical accuracy he heralded the realist trend in 17th-century Netherlandish landscape art.[1]

His son Jacob reworked in 1617 designs of his father for the sixth volume of the Civitates, which was published in Cologne in 1618. Volume 6 contains a homogeneous series of images of cities in Central Europe (in Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and Transylvania), which are very consistent in their graphics. The views are in perspective, and only in a few cases, isometric and stand out through the accuracy of the information, the particular attention to the faithful representation of the territory, the landscape, the road conditions and the power of observation and refinement of interpretation.[5]

Emblems

In England, Hoefnagel also made a set of emblematic drawings entitled Patientia (full title: Traité de la Patience, Par Emblêmes Inventées et desinées par George Hoefnagel à Londres, L’an 1569), which focused on the themes of patience and suffering. The genre-like nature of the work anticipated later Netherlandish emblem books. Patientia also reflected the influence of Neo-stoic philosophy, which was popular in the circle around the Antwerp publisher Christopher Plantin.[2] The book remained in manuscript form and is dated to 1569. The manuscript is kept in the Municipal Library of Rouen, France.

One of the emblems from the series is entitled Patiente cornudo (the patient cuckold). It depicts a scene of public punishment of an adulterous woman and her deceived husband, i.e. the 'patient cuckold'. The Catholic Church regarded both husband and wife guilty in the crime of adultery. The husband has his hands tied and he wears on his head two large branches with their offshoots which resemble large deer antlers. Between the tops of the branches hang bells on a rope. After the man rides a woman, her head covered with a veil and her face hidden behind her own hair. She whips her husband with a string of garlic. Behind them is a crier who heralds the crime of the couple. He has a trumpet and a stalk with which he punishes the couple. Hoefnagel reprised this scene in his View of Seville from 'Civitates orbis terrarium'. Added in the View of Seville is a woman on a donkey who is naked from the waist up. She is the procuress who is also punished. The scene further includes figures who ridicule the couple by holding up their fingers in a 'V' form, an allusion to the 'horned' (cuckolded) husband.[6]

Manuscript illuminations

Hoefnagel was an accomplished miniature painter and is famous for his miniature work on various manuscripts in the collection of the Habsburg dynasty.

The Book of Hours of Philippe of Cleves

His earliest known miniature contributions are found in the The Book of Hours of Philippe of Cleves (Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels). In the late 1570s or early 1580s, Hoefnagel added in the margins of this 15th century devotional book various illuminations. Some of the themes he developed recur in his later book illuminations, such as the split sour orange or the bright orange Maltese cross.[2]

Roman Missal

Between 1581 and 1590, he illustrated the Tridentine version of the Roman missal (now in the National Library in Vienna), a commission for Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria. He added illuminations throughout the missal, which consists of 658 vellum folios. His decorations include nature imagery and grotesque borders. The calendar pages are illuminated with small gaming-boards, instruments and animals linked by strapwork. The images carry emblematic content, typically related to the particular religious text it accompanies or to the patron.[1]

Schriftmusterbuch

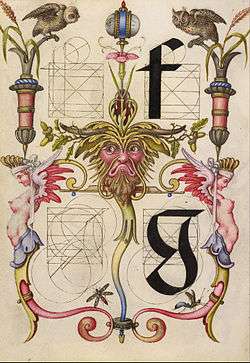

At the request of Emperor Rudolf II Hoefnagel added in the period 1591-1594 miniatures to a manuscript, referred to as Schriftmusterbuch (now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).

The Schriftmusterbuch had been created by court calligrapher Georg Bocskay in 1571-1573 for Emperor Maximilian II. The book consists of 127 pages (of which 119 with text) on parchment. Hoefnagel added miniature illuminations to the original text using watercolour and body color in silver with gold highlights, sometimes with traces of silverpoint for the preparatory drawing. Hoefnagel also added eight sheets, which are entirely by his hand.[7] Hoefnagel used diverse imagery such as flora and fauna, mythology, portraits, city views and battle scenes. The aim was to glorify the Emperor as the supreme terrestrial power and the protector of the Catholic faith.[1]

Mira calligraphiae monumenta

Hoefnagel was also commissioned by Emperor Rudolf II to illustrate the Mira calligraphiae monumenta (the Model Book of Calligraphy) (now in the Getty Museum). He began the work around 1590, more than 15 years after the death of the calligrapher, Georg Bocskay.[8] Like the Musterbuch, this book was originally made by Bocskay to illustrate various calligraphic scripts and also included a constructed alphabet. When the book had come in the possession of Emperor Rudolf II, Hoefnagel added illuminations primarily of plants, fruit and flowers but also included small animals and insects and city views. His illustrations thus provided a survey of the natural world.[9] He further illustrated the minuscule letters of the constructed alphabet with hybrid creatures and fanciful masks. Using his extensive resources of pictorial illusionism, Hoefnagel aimed to demonstrate with his illustrations the superior affective power of images over the written word. It thus argued the superiority of one art form over another.[10] The book is one of the last important examples of European manuscript illumination, produced at a time when printed books had virtually replaced manuscripts.[8]

Hoefnagel's miniature illuminations are regarded as situating themselves in the earlier Flemish miniature tradition and, in particular, the Ghent-Bruges manuscript illuminations of the 15th and 16th century. This is particularly reflected in his meticulous manner of drawing, the use of trompe l’oeil devices (such as cast shadows or stems slipped through fictitious slits in pages) and the naturalistic content. This tradition emphasized illusionism in painting through devices such as three-dimensional modeling of vegetative and other forms and the depiction of details in a precise and life-size manner.[11] Hoefnagel strived to display his virtuosity in his attention for detail as well as his predilection for difficult subjects such as an apple cut in two, a bean pod that is split open or an insect or reptile with iridescent skin.[12]

Natural history studies

-_Plate_I.jpg)

The Four Elements

Hoefnagel received one of his earliest commissions while working for the Dukes in Munich. He produced a four-volume manuscript of natural history miniatures (various folios dated from 1575 to 1582 in various museums including the National Gallery of Art, Washington; Kupferstichkabinet, Berlin; Louvre, Paris and various private collections). The work was entitled Animalia rationalia et insecta (ignis); Animalia quadrupedia et reptilia (terra) ; Animalia aquatilia et conchiliata (aqua); and Animalia volatilia et amphibia (aier) and contains thousands of detailed animals divided according to the four elements (and the book is therefore simply referred to as the Four Elements).

The work resembles an emblem book with its Latin mottoes, epigrams and Bible verses. Hoefnagel did not paint all the works but rather copied from other artists' works including a series of drawings by the Antwerp animal painter Hans Verhagen den Stommen and woodcuts from Konrad Gessner’s Historia animalium. The book was an important monument of 16th-century science by providing a compendium of the entire known animal world.[1]

Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii

His son Jacob published the Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii in 1592 in Frankfurt. The book is a collection of 48 engravings of plants, insects and small animals shown ad vivum made after studies by Joris Hoefnagel.[13] It is divided in four parts of twelve plates (each with separate frontispiece) engraved by Jacob Hoefnagel after designs by his father Joris Hoefnagel.[14] The Italian scholar Filippo Buonanni asserted in 1691 that these engravings are the first published instance of the use of the microscope. However, this assertion of Buonanni is still contested.[15] As the quality of the engravings varies, it is assumed that some of the works were made by members of the family De Bry who resided in Frankfurt.[16]

The prints in the collection were intended not solely as representations of the real world. They also carried a religious meaning as they encouraged the contemplation of god's plan of creation. Like contemporary emblem books each print carried a motto typically referring to god's interference in the world. The prints of the book were used as models by other artists and the Hoefnagel motifs were copied until the 19th century.[4]

Still lifes

Hoefnagel played an important role in the development of still life, and in particular flower still life, painting as an independent genre. An undated flower piece executed by Hoefnagel in the form of a miniature is the first known independent still life. Hoefnagel enlivened his flower pieces with insects and attention to detail typical of his nature studies. This can be seen in his 1589 Amoris Monumentum Matri Chariss(imae) (ex-Nicolaas Teeuwisse 2008).[17]

It has been argued that Hoefnagel’s manuscript illuminations, the prints from the Archetypa studiaque and some drawings on vellum independent from any text (such as the 1594 Flower still life with insects, Ashmolean Museum) stood at the basis of still-life painting as an independent genre. This influence is assumed to have been important in particular on the development of the typical Dutch genre of still lifes with flowers, shells and insects.[11][4] The manner in which Dutch authors and artists represented insects at the beginning of the 17th century was also influenced by Joris Hoefnagel through the intermediary of his sister’s marriage into the influential Dutch Huygens family. After his death, a part of his artistic heritage was bequeathed to the Huygens family, where it was seen by Flemish-born Dutch artist Jacob de Gheyn II who would become one of the earliest flower still life painters.[4]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lee Hendrix. "Hoefnagel, Joris." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 21 July 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Joris Hoefnagel, The Illuminator, in: Lee Hendrix, Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta: A Sixteenth-Century Calligraphic Manuscript Inscribed by Georg Bocksay and Illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel, Volume 1, Getty Publications, 13 Aug, 1992, p. 15-28

- ↑ Biography of Georg Hoefnagel at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

- 1 2 3 4 Karel A. E. Enenkel, Paulus Johannes Smith, Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts, Volume 7, Issue 1, Brill, 2007

- ↑ Irina Baldescu, Joris e Jacob Hoefnagel - Artisti e Viaggiatori: Territorio e vedute di città in Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Liber Sextus, (Köln 1617-1618), in: Studia Patzinika, 6, 2008, p. 7-35 (Italian)

- ↑ José Julio García Arranz, El castigo del "cornudo paciente": un detalle iconográfico en la "Vista de Sevilla" de Joris Hoefnagel (1593), Universidad de Extremadura: Servicio de Publicaciones, 2008 (Spanish)

- ↑ Georg Bocskay and Joris Hoefnagel, Schriftmusterbuch, 1571-1594, Wenen, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 975 at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (Dutch)

- 1 2 Lee Hendrix and Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Nature Illuminated: Flora and Fauna from the Court of the Emperor Rudolf II, Getty Publications, 1997

- ↑ Acquisitions 1986 in: The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal Volume 15 1987, p. 154

- ↑ Lee Hendrix, Mira calligraphiae monumenta: An Overview, in: Lee Hendrix, Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta: A Sixteenth-Century Calligraphic Manuscript Inscribed by Georg Bocksay and Illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel, Volume 1, Getty Publications, 13 Aug, 1992, p. 1-6

- 1 2 Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann and Virginia Roehrig Kaufmann, The Sanctification of Nature: Observations on the Origins of Trompe l'oeil in Netherlandish Book Painting of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Volume 19, 1991, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications, 28 Jan, 1993, pp. 43-64

- ↑ Ernst Kris, Georg Hoefnagel und der wissenschaftliche Naturalismus, in: Ernst Kris, Erstarrte Lebendigkeit, Zwei Untersuchungen, Zürich : Diaphanes, 2012 (German)

- ↑ The Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii at archive.org

- ↑ Frontispiece at The British Museum

- ↑ Edward G. Ruestow, The Microscope in the Dutch Republic: The Shaping of Discovery, Cambridge University Press, 22 Jan, 2004, p. 70

- ↑ Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Neues zu Jacob Hoefnagel, in: Studia Rudolphina no. 10, 2010, p. 196-211 (German)

- ↑ Joris Hoefnagel, Amoris Monumentum Matri Chariss(imae) at Nicolaas Teeuwisse

External links

Media related to Joris Hoefnagel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joris Hoefnagel at Wikimedia Commons- Maps from the Civitates orbis terrarum

- Digital Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (1575–1580) at entomologiitaliani

- Hoefnagel at the National Gallery of Art

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which includes material on Joris Hoefnagel (see index)

- Joris Hoefnagel at google.art.project