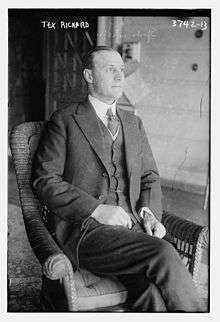

Tex Rickard

| Tex Rickard | |

|---|---|

|

Tex Rickard | |

| Born |

George Lewis Rickard January 2, 1870 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

January 6, 1929 (aged 59) Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupation | Gambler, bartender, boxing promoter |

| Years active | 1896–1929 |

| Known for |

Rebuilt Madison Square Garden First to promote boxing to large audiences |

George Lewis "Tex" Rickard (January 2, 1870 – January 6, 1929) was an American boxing promoter, founder of the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League (NHL), and builder of the third incarnation of Madison Square Garden in New York City. During the 1920s, Tex Rickard was the leading promoter of the day, and he has been compared to P. T. Barnum and Don King. Sports journalist Frank Deford has written that Rickard "first recognized the potential of the star system."[1]

Early years

Rickard was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His youth was spent in Sherman, Texas, where his parents had moved when he was four.[2]

At the age of 23, he was elected marshal of Henrietta, Texas.[3] He married Leona Bittick[2] and acquired the nickname "Tex"[3] at this time.

Rickard went to Alaska, drawn by the discovery of gold there, arriving in November 1895.[3] Thus he was in the region when he learned of the nearby Klondike Gold Rush of 1897. Along with most of the other residents of Circle City, Alaska, he hurried to the Klondike, where he and his partner, Harry Ash, staked claims.[3] They eventually sold their holdings for nearly $60,000.[3] They then opened the Northern Saloon, however Rickard lost everything—including his share of the Northern—through gambling.[3] While working as a poker dealer and bartender at the Monte Carlo saloon and gambling hall, he and Wilson Mizner began promoting boxing matches.[3] In 1899, Rickard (and many others) left to chase the gold strikes in Nome, Alaska.[3] While in Nome, he met Wyatt Earp who was a boxing fan and had officiated a number of matches during his life, including the infamous match between Bob Fitzsimmons and Tom Sharkey in San Francisco on December 2, 1896. The two became lifelong friends, though for a brief period of time ca. 1901, they were competing saloon owners in Nome. During the final week of Rickard's life, Earp learned he was ill and sent him a telegram.[4] Earp died the same month as Rickard.

By 1906, Rickard was running a saloon in Goldfield, Nevada. There he promoted another professional boxing match.[2][3] Rickard temporarily left both boxing and the United States in the early 1910s. This was the time of Jack Johnson's tumultuous reign as heavyweight champion. With the heavyweight champion a fugitive from American justice after Johnson fled following his conviction on Mann Act charges, Rickard decided that there was little money to be made promoting boxing in the U.S. and went to South America. Rickard returned after Jess Willard dethroned Johnson in 1915.

Rickard and 1920s boxing

In 1920, Tex secured the rights to promote live events from Madison Square Garden in New York. By 1924, Rickard began putting together the financing to construct a new Garden, which he completed in 1925.[5]

In the 1920s, the best boxing promoters and managers were instrumental in bringing boxing to new audiences and provoking media and public interest. Arguably the most famous of all three-way partnerships (fighter-manager-promoter) was that of Jack Dempsey (Heavyweight Champion, 1919–1926), his manager Jack Kearns, and Rickard as promoter. Together they grossed US$8.4 million in only five fights between 1921 and 1927 and ushered in a "golden age" of popularity for professional boxing in the 1920s. They were also responsible for the first live radio broadcast of a title-fight and the first million-dollar fight (Dempsey v. Georges Carpentier in 1921).

A key business partner of Rickard's in this period was a concert and boxing promoter named Jess McMahon, who was the grandfather of current World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) promoter Vincent K. McMahon. However, due to Rickard disliking the sport of professional wrestling, he did not co-promote wrestling events with McMahon, and it was not until 1935 that McMahon's son, Vincent J. McMahon, would begin promoting his Capitol Wrestling Corporation events. In spite of these objections to pro wrestling, Rickard and McMahon did promote boxing matches like the December 11, 1925, light-heavyweight championship match between Jack Delaney and Paul Berlenbach.

John L. "Ike" Dorgan was Rickard's press agent[6] and, later, publicity manager for the Garden.

Rickard and hockey

Tex Rickard was awarded an NHL franchise in 1926 to compete with the now-defunct New York Americans. The team was immediately dubbed 'Tex's Rangers', and the nickname stuck. The Rangers were an immediate success, winning a division title in their first season and the Stanley Cup in their second season.

Other achievements

In 1928, Rickard opened Boston Madison Square Garden, eventually known as Boston Garden, the first in a planned series of "Madison Square Gardens" to be built in six other cities; the expense of Boston Garden, Rickard's own death, and the 1929 stock market crash ended the effort.[7] Rickard also founded the South America Land and Cattle Company and the Rickard Texas Oil Company.

Death

Rickard was engaged in fight promotion in Miami Beach when he died at age 59 on January 6, 1929, of complications following an appendectomy.[2] He was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY

References

- ↑ Deford, Frank (1971), Five Strides On The Banked Track, Little, Brown and Company, p. 110

- 1 2 3 4 "Rickard, George Lewis (1871-1929)". The Handbook of Texas Online.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "From the Klondike muck to Madison Square Gardens". The Hougen Group of Companies. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ↑ Barra, Alan (November 26, 1995). "BACKTALK;When Referee Wyatt Earp Laid Down the Law". New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Tex Rickard – The most dynamic fight promoter in history www.boxinginsider.com

- ↑ Roberts, Randy. Jack Dempsey: The Manassa Mauler. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2003, p. 140. ISBN 0-252-07148-4, ISBN 978-0-252-07148-5

- ↑ "BACKTALK; The Last Days of a Garden Where Memories Grew". The New York Times. April 16, 1995. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

External links

- Works by or about Tex Rickard at Internet Archive

- Yukon Nuggets: From the Klondike muck to Madison Square Gardens