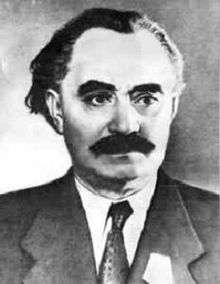

Georgi Dimitrov

| Georgi Dimitrov

Георги Димитров Михайлов | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party | |

|

In office December 1946 – 2 July 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Khristo Kabakchiev |

| Succeeded by | Valko Chervenkov |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Bulgaria | |

|

In office 23 November 1946 – 2 July 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Kimon Georgiev |

| Succeeded by | Vasil Kolarov |

| Head of the International Policy Department of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

|

In office 27 December 1943 – 29 December 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Suslov |

| General Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Communist International | |

|

In office 1935–1943 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov

(Bulgarian: Георги Димитров Михайлов) 18 June 1882 Kovachevtsi, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Died |

2 July 1949 (aged 67) Barvikha Sanatorium, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Bulgarian Communist Party |

| Spouse(s) |

Ljubica Ivošević (1906–1933) Roza Yulievna (until 1949) |

| Profession | compositor, revolutionary, politician |

Georgi Dimitrov Mikhaylov (Bulgarian: Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgi Mikhaylovich Dimitrov (Russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров) (June 18, 1882 – July 2, 1949), was a Bulgarian communist politician. He was the first communist leader of Bulgaria, from 1946 to 1949. Dimitrov led the Communist International from 1934 to 1943. He was a theorist of capitalism who expanded Lenin's ideas by arguing that fascism was the dictatorship of the most reactionary elements of financial capitalism.

Early life

Georgi Dimitrov was born in Kovachevtsi in today's Pernik Province, the first of eight children to working class parents from Pirin Macedonia (a mother from Bansko and a father from Razlog). His mother, Parashkeva Doseva, was a Protestant Christian, and his family is sometimes described as Protestant.[1] The family moved to Radomir and then to Sofia.[2] Dimitrov trained as a compositor and became active in the labor movement in the Bulgarian capital.

Career

Dimitrov joined the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers' Party in 1902, and in 1903 followed Dimitar Blagoev and his wing, as it formed the Social Democratic Labour Party of Bulgaria ("The Narrow Party"). This party became the Bulgarian Communist Party in 1919, when it affiliated to Bolshevism and the Comintern. From 1904 to 1923, he was Secretary of the Trade Unions Federation; in 1915 (during World War I) he was elected to the Bulgarian Parliament and opposed the voting of a new war credit, being imprisoned until 1917.

In June 1923, when Prime Minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski was deposed through a coup d'état, Stamboliyski's Communist allies, who were initially reluctant to intervene, organized an uprising against Aleksandar Tsankov. Dimitrov took charge of the revolutionary activities, and managed to resist the clampdown for a whole week. He and the leadership fled to Yugoslavia and received a death sentence in absentia. Under various pseudonyms, he lived in the Soviet Union until 1929, when he relocated to Germany, where he was given charge of the Central European section of the Comintern.

Leipzig trial and Comintern leadership

In 1932 Dimitrov was appointed Secretary General of the World Committee Against War and Fascism, replacing Willi Münzenberg.[3] In 1933 he was arrested in Berlin for alleged complicity in setting the Reichstag on fire (see Reichstag fire). Dimitrov famously decided to refuse counsel and defend himself against his Nazi accusers, primarily Hermann Göring, using the trial as an opportunity to defend the ideology of communism. Explaining why he chose to speak in his own defense, Dimitrov argued:

I admit that my tone is hard and grim. The struggle of my life has always been hard and grim. My tone is frank and open. I am used to calling a spade a spade. I am no lawyer appearing before this court in the mere way of his profession. I am defending myself, an accused communist. I am defending my political honor, my honor as a revolutionary. I am defending my communist ideology, my ideals. I am defending the content and significance of my whole life. For these reasons every word which I say in this court is a part of me, each phrase is the expression of my deep indignation against the unjust accusation, against the putting of this anti-Communist crime, the burning of the Reichstag, to the account of the Communists.[4]

During the Leipzig Trial, Dimitrov's calm conduct of his defence and the accusations he directed at his prosecutors won him world renown.[5] On August 24, 1942, for instance, the American newspaper The Milwaukee Journal declared that in the Leipzig Trial, Dimitrov displayed "the most magnificent exhibition of moral courage even shown anywhere."[6] In Europe, a popular saying spread across the Continent: “There is only one brave man in Germany, and he is a Bulgarian.”[7]

After his fame grew in the wake of the Leipzig Trial, Joseph Stalin appointed Dimitrov the head of the Comintern in 1934, just two years before the outbreak of hostilities in Spain. In 1935, at the 7th Comintern Congress, Dimitrov spoke for Stalin when he advocated the Popular Front strategy, meant to consolidate Soviet ideology as mainstream Anti-Fascism — one that was later employed during the Spanish Civil War.

Leader of Bulgaria

In 1944, Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria after 22 years in exile and became leader of the Communist party there. After the onset of undisguised Communist rule in 1946, Dimitrov succeeded Kimon Georgiev as Prime Minister, while keeping his Soviet Union citizenship. Dimitrov started negotiating with Josip Broz Tito on the creation of a Federation of the Southern Slavs, which had been underway since November 1944 between the Bulgarian and Yugoslav Communist leaderships.[8] The idea was based on the idea that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria were the only two homelands of the Southern Slavs, separated from the rest of the Slavic world. The idea eventually resulted in the 1947 Bled accord, signed by Dimitrov and Tito, which called for abandoning frontier travel barriers, arranging for a future customs union, and Yugoslavia's unilateral forgiveness of Bulgarian war reparations. The preliminary plan for the federation included the incorporation of the Blagoevgrad Region ("Pirin Macedonia") into the Socialist Republic of Macedonia and the return of the Western Outlands from Serbia to Bulgaria. In anticipation of this, Bulgaria accepted teachers from Yugoslavia who started to teach the newly codified Macedonian language in the schools in Pirin Macedonia and issued the order that the Bulgarians of the Blagoevgrad Region should claim а Macedonian identity.[9]

However, differences soon emerged between Tito and Dimitrov with regard to both the future joint country and the Macedonian question. Whereas Dimitrov envisaged a state where Yugoslavia and Bulgaria would be placed on an equal footing and Macedonia would be more or less attached to Bulgaria, Tito saw Bulgaria as a seventh republic in an enlarged Yugoslavia tightly ruled from Belgrade.[10] Their differences also extended to the national character of the Macedonians - whereas Dimitrov considered them to be an offshoot of the Bulgarians,[11] Tito regarded them as an independent nation which had nothing to do whatsoever with the Bulgarians.[12] Thus the initial tolerance for the Macedonization of Pirin Macedonia gradually grew into outright alarm.

By January 1948, Tito's and Dimitrov's plans had become an obstacle to Stalin's aspirations for total control over the new Eastern Bloc.[8] Stalin invited Tito and Dimitrov to Moscow regarding the recent rapprochement between the two countries. Dimitrov accepted the invitation, but Tito refused, and sent Edvard Kardelj, his close associate, instead.[8] The resulting fall-out between Stalin and Tito in 1948 gave the Bulgarian Government an eagerly-awaited opportunity of denouncing Yugoslav policy in Macedonia as expansionistic and of revising its policy on the Macedonian question.[13] The ideas of a Balkan Federation and a United Macedonia were abandoned, the Macedonian teachers were expelled and teaching of Macedonian throughout the province was discontinued. Despite the fallout, Yugoslavia did not reverse its position on renouncing Bulgarian war reparations, as defined in the 1947 Bled accord.

Personal life

In 1906, Dimitrov married his first wife, Serbian emigrant milliner, writer and socialist Ljubica Ivošević, with whom he lived until her death in 1933.[2] While in the Soviet Union, Dimitrov married his second wife, the Czech-born Roza Yulievna, who gave birth to his only son, Mitya, in 1936. The boy died at age seven of diphtheria. While Mitya was alive, Dimitrov adopted Fani, a daughter of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China.[2]

Death

Dimitrov died on 2 July 1949 in the Barvikha sanatorium near Moscow. The rising speculations[8][14] that he had been poisoned have never been confirmed, although his health seemed to deteriorate quite abruptly. The supporters of the poisoning theory claim that Stalin did not like the "Balkan Federation" idea of Dimitrov and his closeness with Tito.[8][14] A state consisting of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria would be too large and independent to be controlled by Moscow.

Opponents claim that Dimitrov was the most loyal "lap dog" of Stalin and Stalin did not have a real reason to kill him. Stalin never forgot the "betrayal" of Dimitrov. However, the anti-Yugoslav (anti-Titoist) trials and executions of Communist leaders orchestrated by Stalin in the Eastern Bloc countries in 1949 did little to calm these suspicions.[15] Dimitrov's body was embalmed and placed on display in Sofia's Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum. After the fall of Communism in Bulgaria, his body was buried in Sofia's central cemetery in 1990. His mausoleum was torn down in 1999.

Legacy outside Bulgaria

After the 1963 Skopje earthquake, Bulgaria joined the international reconstruction effort by donating funds for the construction of a high school, which opened in 1964. In order to honor the donor country's first post-World War II president, the high school was named Georgi Dimitrov, a name it still bears today.[16]

A massive painted statue of Dimitrov survives in the centre of Place Bulgarie in Cotonou, Republic of Benin, two decades after the country abandoned Marxism-Leninism and the colossal statue of Vladimir Lenin was removed from Place Lenine. Few Beninois are aware of the history of the statue or its subject. There is also an important avenue (#114) named for him in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, despite the three decades that have passed since the end of Communist rule.

A main avenue in the Nuevo Holguin neighborhood, which was built during the 1970s and 1980s in the city of Holguin, Cuba is named after him.

During the times of the communist rule, an important chemical factory in Bratislava was called "Chemické závody Juraja Dimitrova" (colloquially Dimitrovka) in his honour. After the Velvet revolution, it was renamed Istrochem.

There are four cities named after Georgi Dimitrov in the world in Bulgaria, Russia, Serbia and Armenia. Myrnohrad in Ukraine was named Dymytrov between 1972 and 2016.

The square Fővám tér in Budapest, Hungary was named after Dimitrov between 1949 and 1991.

In then-East Berlin's Pankow district, a street that since 1874 had been named Danziger Straße — after the formerly German city Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) — was in 1950 renamed Dimitroffstraße (Dimitrov Street) by the Communist East German regime. After German unification, the Berlin Senate in 1995 restored the street's name to Danziger Straße. In Bucharest a boulevard was named after him (Bulevardul Dimitrov), although this name was changed after 1990 to a former Romanian king (Bulevardul Ferdinand).

Works

References

- ↑ Staar, Richard Felix (1982). Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Hoover Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8179-7692-7.

- 1 2 3 Ценкова, Искра (21–27 March 2005). "По следите на червения вожд" (in Bulgarian). Тема. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ Ceplair, Larry (1987). Under the Shadow of War: Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and Marxists, 1918-1939. Columbia University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-231-06532-0. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ Georgi Dimitrov, And Yet It Moves: Concluding Speech before the Leipzig Trial, Sofia: Sofia Press, 1982, pg. 15

- ↑ Eichmann in Jerusalem, Revised and enlarged edition, The Viking Press, New York, 1965, p. 188

- ↑ "The Man who defied Goering, Yet Lived," The Milwaukee Journal,: https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=KKkWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5SIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4517%2C3619637

- ↑ John D. Bell, The Bulgarian Communist Party from Blagoev to Zhivkov, Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1985, pg. 47

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gallagher, T. (2001). Outcast Europe: The Balkans, 1789-1989, from the Ottomans to Milošević. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 9780415270892. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ Nationalism from the Left: The Bulgarian Communist Party During the Second World War and the Early Post-War Years, Yannis Sygkelos, BRILL, 2011, ISBN 9004192085, p. 156.

- ↑ H.R. Wilkinson Maps and Politics. A Review of the Ethnographic Cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool, 1951. pp. 311-312.

- ↑ Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise, Viktor Meier, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 1134665113, p. 183.

- ↑ Hugh Poulton Who are the Macedonians?, C. Hurst & Co, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-534-0. pp. 107-108.

- ↑ H.R. Wilkinson Maps and Politics. A Review of the Ethnographic Cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool, 1951. p. 312.

- 1 2 Chary, F.B. (2011). The History of Bulgaria. ABC-CLIO. p. 131. ISBN 9780313384479. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ Leffler, M.P.; Westad, O.A. (2010). The Cambridge History of the Cold War. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780521837194. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ http://www.georgidimitrov.schools.edu.mk/angliski/index.php

Further reading

- Marietta Stankova, Georgi Dimitrov: A Life, London: I. B. Tauris, 2010

- Dalin and Firsov, Dimitrov and Stalin, 1934-1943: Letters from the Soviet Archives, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000

- Dimitrov and Banac, The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933-1949, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Georgi Dimitrov |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgi Dimitrov. |

- Georgi Dimitrov Reference Archive at Marxist Internet Archive.

- (Chinese)共产国际为中共提供财政援助情况之考察 Yang Kuisong:Study on the financial assisitants to CCP by Comintern

- (Chinese)抗战期间共产国际与中共关系文献资料述评 Yang Kuison:The analysis of historical documents between Comintern and CCP during the Sino-Japanese War.

- Video A Better Tomorrow: The Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum from UCTV (University of California)