Girolamo Mercuriale

| Girolamo Mercuriale | |

|---|---|

Girolamo Mercuriale | |

| Born |

September 30, 1530 Forlì |

| Died |

November 8, 1606 (aged 76) Forlì |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Fields | Medicine, Botany |

| Alma mater | University of Padua, University of Bologna |

| Doctoral students | Gaspard Bauhin |

| Known for | De arte gymnastica |

- For Saint Mercurialis of Forlì, see Saint Mercurialis. For the plant genus see Mercurialis (plant).

Girolamo Mercuriale (Italian: Geronimo Mercuriali; Latin: Hieronymus Mercurialis, Hyeronimus Mercurialis) (September 30, 1530 – November 8, 1606) was an Italian philologist and physician, most famous for his work De Arte Gymnastica.

Biography

Born in the city of Forlì, the son of Giovanni Mercuriali, also a doctor, he was educated at Bologna, Padua and Venice, where he received his doctorate in 1555. Settling in Forli, he was sent on a political mission to Rome. The pope at the time was Paul IV.

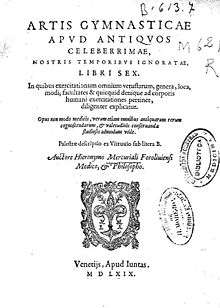

In Rome, he made favorable contacts and had free access to the great libraries where, with sweeping enthusiasm, he studied the classical and medical literature of the Greeks and Romans. His studies of the attitudes of the ancients toward diet, exercise, and hygiene and the use of natural methods for the cure of disease culminated in the publication of his De Arte Gymnastica (Venice, 1569). With its explanations concerning the principles of physical therapy, it is considered the first book on sports medicine. The illustrations which accompanied the second edition of the work (1573) proved incredibly fertile to the Western imagination regarding the nature of athletics in the Classical world. Modern scholarship has recognized that these illustrations were largely speculative creations of Mercuriale and his collaborators.[1] (It was not however the first Renaissance book about the benefits of exercise; Cristobal Méndez's Libro del Exercicio (1553), which was rediscovered in 1930, predates it by 16 years.)[2][3]

The book De Arte Gymnastica brought Mercuriale fame. He was called to occupy the chair of practical medicine in Padua in 1569. During this time, he translated the works of Hippocrates, and, armed with this knowledge, wrote De morbis cutaneis (1572), considered the first scientific tract on skin diseases; De morbis muliebribus ("On the diseases of women") (1582); De morbis puerorum ("On the diseases of children") (1583); De oculorum et aurium affectibus ("The eys and ears and emotions"); and "Censura e dispositio operum Hippocratis" (Venice, 1583). In De morbis puerorum, Mercuriali observed contemporary trends in child-rearing. He wrote that women generally finished breastfeeding an infant exclusively after the third month and entirely after around thirteen months.

In 1573, he was called to Vienna to treat the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. The emperor, pleased with the treatment he received (although he was to die three years later), made him an imperial count palatine.

He returned home in the following years; in 1575, the Venetian Senate awarded him a six-year contract as a professor at the University of Padua. Although he was largely hailed as a hero of the city, his reputation would take a sharp turn downwards after his inept handling of the outbreak of plague in Venice in 1576-1577. Mercuriale was summoned by the Venetian government to head a team of medical professionals who would advise about the disease. Arguing against the quarantining and use of lazarettos by the Board of Health, Mercuriale maintained that the disease infecting Venice could not possibly be plague. He and another medical professor, Girolamo Capodivacca, offered to personally treat the sick in Venice on the condition that the quarantines and other precautions put in place by the Board of Health be lifted. The professors and their assistants traveled freely between infected and safe houses, administering treatment, to the horror of the Board of Health and officials in Padua and surrounding cities, who worried the disease would spread. When Mercuriali and Capodivacca began their treatment of the sick in Venice, the death toll had come to a near halt—this was one of the reasons they believed it could not be the true plague. However, by the end of June, the month when they began their work, it rose at an incredible rate. By the beginning of July, the Senate ordered Mercuriale and Capodivacca to be quarantined themselves and it was largely believed that their questionable methods were the reason for the spread of the plague, which eventually claimed 50,000 Venetians.[4]

However, Mercuriale salvaged his own reputation in the following years with the 1577 publication of De Pestilentia, his treatise about the plague, which had been delivered as a series of lectures at the University of Padua.

Mercuriale was a prolific writer, though many books were ascribed to him that were compiled from the works of others. He remained in Padua until 1587, when he began teaching at the University of Bologna. In 1593, he was called by Ferdinando de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to Pisa. Cosimo wanted to increase the prestige of the university there and offered a record salary of 1,800 gold crowns, to become 2,000 gold crowns after the second year.

Mercuriale returned to Forlì in 1606 and died there a few months later.

Among his many disciples was the Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin.

On 11 March 2009, the Olympic Museum in Lausanne hosted a colloquium given by the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Geneva commemorating the 400th anniversary of the death of Girolamo Mercuriale.[5]

Works

- Artis gymnasticae apud antiquos celeberrimae, nostris temporis ignoratae, libri sex. Venice, 1569. Critical Edition: Girolamo Mercuriale: De arte gymnastica. The Art of Gymnastics, ed., Concetta Pennuto; English trans. Vivian Nutton, Florence 2008 ISBN 978-88-222-5804-5

- De morbis cutaneis, et omnibus corporis humani excrementis tractatus locupletissimi..., Venice, 1572

- De pestilentia, Venice, 1577

- De morbis puerorum tractatus locupletissimi..., Venice, 1583

- De venenis, et morbis venenosis tractatus locupletissimi..., Venice, 1584

- De morbis muliebribus libri, Venice, 1587

- De venenis, et morbis venenosis tractatus locupletissimi, Venice, 1588

- De morbis puerorum tractatus locupletissimi, Venice, 1588

- Variarum lectionum, in medicinae scriptoribus & aliis, libri sex, 1598

References

- ↑ Vivian Nutton (2010) "Girolamo Mercuriale" in The Classical Tradition ed. Anthony Grafton et al. Cambridge: Belknap press. 583: "That almost all of this material can now be shown to be the result of imaginative reconstruction, or straightforward forgery, was unknown to his readers . . ."

- ↑ Libro del Ejercicio Corporal y de sus Provechos por el cual cada uno Podra entender que Ejercicio le sea Necesario para Conservar su Salud

- ↑ Book of Bodily Exercise

- ↑ Richard Palmer, "Girolamo Mercuriale and the Plague of Venice," in Girolamo Mercuriale: Medicina e Cultura nell'Europa del Cinquecento, ed. Alessandro Arcangeli and Vivian Nutton (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2008).

- ↑ "Prevention and Sport at the Olympic Museum.". Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique. Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Girolamo Mercuriali. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- DE HIERONYMI MERCURIALE VITA ET SCRIPTIS

- Full text De arte gymnastica from Wielkopolska Digital Library

- Works of Mercuriale at the Munich Digitization Center

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Girolamo Mercuriale in .jpg and .tiff format.

Notes

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.