The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

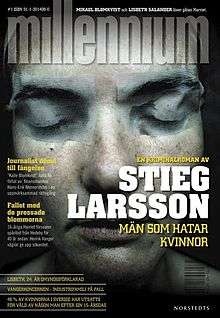

First edition (Swedish) | |

| Author | Stieg Larsson |

|---|---|

| Original title | Män som hatar kvinnor |

| Translator | Reg Keeland, pseudonym of Steven T. Murray |

| Country | Sweden |

| Language | Swedish |

| Series | Millennium |

| Genre | Crime, mystery, thriller, Scandinavian noir |

| Publisher | Norstedts Förlag (Swedish) |

Publication date | August 2005 |

Published in English | January 2008 |

| Media type | Print (paperback, hardback) |

| ISBN |

978-91-1-301408-1 (Swedish) ISBN 978-1-84724-253-2 (English) |

| OCLC | 186764078 |

| Followed by | The Girl Who Played with Fire (2006) |

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (original title in Swedish: Män som hatar kvinnor; in English: Men Who Hate Women) is a psychological thriller novel by the late Swedish author and journalist Stieg Larsson (1954–2004), which was published posthumously in 2005 to become an international best-seller.[1] It is the first book of the Millennium series.

Background

Larsson spoke of an incident which he said occurred when he was 15: he stood by as three men gang-raped an acquaintance of his named Lisbeth. Days later, racked with guilt for having done nothing to help her, he begged her forgiveness—which she refused to grant. The incident, he said, haunted him for years afterward and in part inspired him to create a character named Lisbeth who was also a rape survivor.[2][3] The veracity of this story has been questioned since Larsson's death, after a colleague from Expo magazine reported to Rolling Stone that Larsson had told him he had heard the story secondhand and retold it as his own.[4] The murder of Catrine da Costa was also an inspiration when he wrote the book.[5]

With the exception of the fictional Hedestad,[6] the novel takes place in actual Swedish towns. The magazine Millennium in the books has characteristics similar to that of Larsson's magazine, Expo, such as its socio-political leanings and its financial difficulties.[7]

Both Larsson's longtime partner Eva Gabrielsson and English translator Steven T. Murray have said that Christopher Maclehose (who works for British publisher Quercus) "needlessly prettified" the English translation; as such Murray requested he be credited under the pseudonym "Reg Keeland."[8] The English release also changed the title, even though Larsson specifically refused to allow the Swedish publisher to do so, and the size of Salander's dragon tattoo; from a large piece covering her entire back, to a small shoulder tattoo.[9]

Plot

In December 2002, Mikael Blomkvist, publisher of the Swedish political magazine Millennium, loses a libel case involving allegations about billionaire industrialist Hans-Erik Wennerström. Blomkvist is sentenced to three months (deferred) in prison, and ordered to pay hefty damages and costs. Soon afterwards, he is invited to meet Henrik Vanger, the retired CEO of the Vanger Corporation, unaware that Vanger has checked into his personal and professional history; the investigation of Blomkvist's circumstances has been carried out by Lisbeth Salander, a brilliant but deeply troubled researcher and computer hacker.

Vanger promises to provide Blomkvist with evidence against Wennerström in return for discovering what happened to Vanger's grandniece, Harriet, who disappeared in 1966; Vanger believes she was murdered by a member of the family. Harriet disappeared during a family gathering at the Vanger estate on Hedeby Island, when the island was temporarily cut off from the mainland by a traffic accident on the bridge.

Blomkvist moves to the island and begins to research the Vanger family history and Harriet's disappearance. As he does so, he meets most of the remaining Vanger clan, including Martin, current CEO of the company; Isabella, Martin's mother; and Cecilia, a headmistress who was Harriet's friend, though her sister Anita was closer both in age and friendship to the missing girl.

Salander was ruled legally incompetent as a child and is under the care of a legal guardian, Holger Palmgren. When Palmgren suffers a stroke, he is replaced by Nils Bjurman, who uses his position to extort sexual favors from her and eventually rapes her. After using a hidden camera to record her assault, Salander takes her revenge, torturing Bjurman and threatening to ruin him unless he gives her full control of her life and finances. She then uses a tattoo machine to brand him as a rapist.

Despite all expectation to the contrary, Blomkvist identifies new evidence in Harriet's disappearance. One clue is a pair of photographs, detailing Harriet's sudden discomfort at the sight of a young man in a prep school blazer. Another lies in Harriet's journal, which contains a set of five names and five-digit numbers believed to be old telephone numbers; however, Blomkvist's daughter Pernilla, passing through on the way to Bible camp, identifies them as passages from the Book of Leviticus. They describe rules about the treatment and punishment of women, and Blomkvist correlates one of them with the grotesque murder of a Vanger Corporation secretary in 1949. Blomkvist realizes that he may be on the trail of a serial killer, and the scope of the resulting research makes Blomkvist request a research assistant. Vanger's lawyer suggests Salander.

When he sees the report she prepared for Vanger, Blomkvist realises that Salander has hacked into his computer. He confronts her and asks her to help him with the investigation, to which she agrees. The two eventually become lovers, but Salander continues to keep Blomkvist at an emotional distance. Their suspicions are heightened when a local cat is left dismembered on Blomkvist's porch, and Blomkvist is fired upon from a distance during an afternoon jog.

Blomkvist and Salander uncover the remaining four murders described in Harriet's journal, as well as several more that fit the profile: women who are sexually assaulted and then slain in accordance with (or in an exaggerated parody of) a Leviticus verse. Moreover, most of the murders occurred in locations where the Vanger Corporation did business.

They settle on Gottfried Vanger, Martin and Harriet's father, as a likely candidate but are stymied when he is discovered to have predeceased the last victim. While Salander continues to hunt through Vanger Corporation archives, Blomkvist manages to identify the antagonist who frightened Harriet so: her brother Martin. Martin takes Blomkvist prisoner, reveals that Gottfried "initiated" him into the ritual rape and murder of women before his own death, and implies that Gottfried sexually abused both him and Harriet. Martin admits to murdering dozens of women but denies killing his sister. He decides to rid himself of Blomkvist once and for all, but Salander—who had discovered the connections independently—arrives and hits Martin over the head with a golf club before cutting Blomkvist out of his restraints. Martin flees by car, pursued by Salander on her motorbike, and chooses his own fate by purposely colliding headlong with an oncoming truck.

Believing that Cecilia's sister Anita, who now lives in London, is the only relative who might know something about Harriet's fate, Blomkvist and Salander pursue that lead and learn Harriet is still alive and is living under Anita's name in Australia. When Blomkvist flies there to meet her, Harriet tells him the truth about her disappearance: her father and brother had repeatedly raped her, until she killed her father in self-defense. Martin was sent away to preparatory school, but he returned the day of her disappearance. Harriet realized she needed to escape, so she found a place to hide during the tumult of the traffic accident, and Anita smuggled her to the mainland the next morning.

Blomkvist persuades her to return to Sweden, where she reunites with Henrik. Blomkvist then accompanies Salander to her mother's funeral.

Blomkvist learns that the evidence against Wennerström that Vanger promised him is useless, long past its statute of limitations. However, Salander has already hacked Wennerström's computer and discovered that his crimes go far beyond what Blomkvist documented. Using her evidence, Blomkvist prints an exposé and book which ruin Wennerström and catapults Millennium to national prominence. Salander, using her hacking skills, succeeds in stealing some 2.6 billion kr (about $260 million USD) from Wennerström's secret bank account.

Blomkvist and Salander spend Christmas together in his holiday retreat. A couple of days later, she goes to Blomkvist's home, intending to declare her love for him, but backs away when she sees him with his long-time lover and business partner Erika Berger.

As a postscript, Salander continues to monitor Wennerström and after six months, anonymously informs a lawyer in Miami of his whereabouts. He is found in Marbella, Spain, dead, shot three times in the head.

Characters

- Mikael Blomkvist – Journalist, publisher, and part-owner of the monthly political magazine Millennium

- Lisbeth Salander – Freelance surveillance agent and researcher, specialising in investigating people on behalf of Milton Security

- Henrik Vanger – Retired industrialist and former CEO of Vanger Corporation

- Harriet Vanger – Henrik's grandniece

- Martin Vanger – Harriet's brother and CEO of the Vanger Corporation

- Gottfried Vanger – Martin and Harriet's deceased father

- Isabella Vanger – Gottfried Vanger's widow, and Martin and Harriet's mother

- Cecilia Vanger – Daughter of Harald Vanger and one of Henrik's nieces

- Anita Vanger – Daughter of Harald Vanger and one of Henrik's nieces, resident in London

- Birger Vanger – Son of Harald Vanger and one of Henrik's nephews.

- Harald Vanger – Henrik's brother, member of the Swedish Nazi Party

- Hans-Erik Wennerström – Corrupt billionaire financier

- Robert Lindberg – Banker and Blomkvist's source for the libelous story

- William Borg – Blomkvist's nemesis

- Monica Abrahamsson – Blomkvist's wife, whom he married in 1986 and divorced in 1991

- Pernilla Abrahamsson – Their daughter, who was born in 1986

- Holger Palmgren – Salander's legal guardian and lawyer, who is disabled by a stroke

- Nils Bjurman – Salander's legal guardian and lawyer after Palmgren

- Erika Berger – Editor-in-chief/majority owner of Millennium monthly magazine, and Blomkvist's long-standing lover

- Dirch Frode – Former lawyer for Vanger Corporation, now lawyer with one client: Henrik Vanger

- Dragan Armansky – CEO and COO of Milton Security

- Plague – Computer hacker/genius

- Christer Malm – Director, art designer, and part-owner of Millennium

- Janne Dahlman – Managing editor of Millennium

- Gustaf Morell – Retired Detective Superintendent

- Anna Nygren – Henrik Vanger's housekeeper

- Gunnar Nilsson – Henrik's caretaker

Major themes

Larsson makes several literary references to the genre's classic forerunners and comments on contemporary Swedish society.[10] Reviewer Robert Dessaix writes, "His favourite targets are violence against women, the incompetence and cowardice of investigative journalists, the moral bankruptcy of big capital and the virulent strain of Nazism still festering away ... in Swedish society."[1] Cecilia Ovesdotter Alm and Anna Westerstahl Stenport write that the novel "reflects—implicitly and explicitly—gaps between rhetoric and practice in Swedish policy and public discourse about complex relations between welfare state retrenchment, neoliberal corporate and economic practices, and politicised gender construction. The novel, according to one article, endorses a pragmatic acceptance of a neoliberal world order that is delocalized, dehumanized and misogynistic."[11]

Alm and Stenport add, "What most international (and Swedish) reviewers overlook is that the financial and moral corruptibility at the heart of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is so profound as to indict most attributes associated with contemporary Sweden as democratic and gender-equal. The novel is in fact far from what American critic Maureen Corrigan calls an "unflinching ... commonsense feminist social commentary". (Corrigan's article was "Super-Smart Noir With a Feminist Jolt," National Public Radio, 23 September 2008.)[11]

Larsson further enters the debate as to how responsible criminals are for their crimes, and how much is blamed on upbringing or society.[1] For instance, Salander has a strong will and assumes that everyone else does, too. She is portrayed as having suffered every kind of abuse in her young life, including an unjustly ordered commitment to a psychiatric clinic and subsequent instances of sexual assault suffered at the hands of her court-appointed guardian.

Maria de Lurdes Sampaio, in the journal Cross-Cultural Communication, asserts that, "Blomkvist, a modern Theseus, leads us to the labyrinth of the globalized world, while the series' protagonist, Lisbeth Salander, modeled on the Amazon, is an example of the empowerment of women in crime fiction by playing the role of the 'tough guy' detective, while also personifying the popular roles of the victim, the outcast and the avenger." In this context, she discusses "Dialogues with Greek tragedy... namely Salander's struggles with strong father figures." Sampaio also argues,

Then, like so many other writers and moviemakers, Larsson plays with people's universal fascination for religious mysteries, enigmas and hermeneutics, while highlighting the way the Bible and other religious books have inspired hideous serial criminals throughout history. There are many passages dedicated to the Hebrew Bible, to the Apocrypha and to the controversies surrounding different Church's branches. The transcription of Latin expressions (e.g., "sola fide" or "claritas scripturae") together with the biblical passages, which provide the clues to unveil the secular mysteries, proves that Larsson was well acquainted with Umberto Eco's bestsellers and with similar plots. There are many signs of both The Name of the Rose and of Foucault's Pendulum in the Millennium series, and in some sense these two works are contained in the first novel.[12]

Locked room mystery

Larsson writes within the novel, in Chapter 12, "It's actually a fascinating case. What I believe is known as a locked room mystery, on an island. And nothing in the investigation seems to follow normal logic. Every question remains unanswered, every clue leads to a dead end." He supplies a family tree delineating the relationships of five generations of the Vanger family.

Reception and awards

The novel was released to great acclaim in Sweden and later, on its publication in many other European countries. In the original language, it won Sweden's Glass Key Award in 2006 for best crime novel of the year. It also won the 2008 Boeke Prize, and in 2009 the Galaxy British Book Awards[13] for Books Direct Crime Thriller of the Year, and the prestigious Anthony Award[14][15] for Best First Novel.

Larsson was awarded the ITV3 Crime Thriller Award for International Author of the Year in 2008.[16]

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo received mixed reviews from American critics. It debuted at number four on The New York Times Best Seller list.[11] Alex Berenson wrote in The New York Times , "The novel offers a thoroughly ugly view of human nature"; while it "opens with an intriguing mystery" and the "middle section of Girl is a treat, the rest of the novel doesn't quite measure up. The book's original Swedish title was Men Who Hate Women, a label that just about captures the subtlety of the novel's sexual politics."[17] The Los Angeles Times said "the book takes off, in the fourth chapter: From there, it becomes classic parlor crime fiction with many modern twists....The writing is not beautiful, clipped at times (though that could be the translation by Reg Keeland) and with a few too many falsely dramatic endings to sections or chapters. But it is a compelling, well-woven tale that succeeds in transporting the reader to rural Sweden for a good crime story."[18] Several months later, Matt Selman said the book "rings false with piles of easy super-victories and far-fetched one-in-a-million clue-findings."[19] Richard Alleva, in Commonweal, wrote that the novel is marred by "its inept backstory, banal characterizations, flavorless prose, surfeit of themes (Swedish Nazism, uncaring bureaucracy, corporate malfeasance, abuse of women, etc.), and—worst of all—author Larsson's penchant for always telling us exactly what we should be feeling."[20]

On the other hand, Dr. Abdallah Daar, writing for Nature, said, "The events surrounding the great-niece's disappearance are meticulously and ingeniously pieced together, with plenty of scientific insight."[21] The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote, "It's a big, intricately plotted, darkly humorous work, rich with ironies, quirky but believable characters and a literary playfulness that only a master of the genre and its history could bring off."[22]

As of 3 June 2011, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo had sold over 3.4 million copies in hardcover or ebook formats, and 15 million copies altogether, in the United States.[23]

Book of essays

Wiley published a collection of essays, edited by Eric Bronson, titled The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Philosophy (2011).[24]

Film adaptations

- The Swedish film production company Yellow Bird created film versions of the first three Millennium books, all three films released in 2009, beginning with The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, directed by Danish filmmaker Niels Arden Oplev. The protagonists were played by Michael Nyqvist and Noomi Rapace.

- A Hollywood film adaptation of the book, directed by David Fincher, was released in December 2011. The main characters were portrayed by Daniel Craig[25] and Rooney Mara.[26]

- Millennium (miniseries), a Swedish six-part television miniseries based on the film adaptations of Stieg Larsson's series of the same name, was broadcast on SVT1 from 20 March 2010 to 24 April 2010. The series was produced by Yellow Bird in cooperation with several production companies, including SVT, Nordisk Film, Film i Västm, and ZDF Enterprises.

- Dragon Tattoo Trilogy: Extended Edition is the title of the TV miniseries release on DVD, Blu-ray, and video on demand in the US. This version of the miniseries comprises nine hours of story content, including over two hours of additional footage not seen in the theatrical versions of the original Swedish films. The four-disc set includes: THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO – EXTENDED EDITION, THE GIRL WHO PLAYED WITH FIRE – EXTENDED EDITION, THE GIRL WHO KICKED THE HORNET’S NEST – EXTENDED EDITION, and a BONUS DISC including two hours of special features.[27]

Parodies

- The Dragon with the Girl Tattoo (2010) – Adam Roberts

- The Girl with the Sturgeon Tattoo () – Lars Arffssen

- The Girl who Fixed the Umlaut (2010) – Nora Ephron[28]

- The Girl with the Sandwich Tattoo: A cruel parody (2013) – Dragon Stiegsson

- The Coach with the Dragon Tattoo (2016) - Patrick Ness

References

- 1 2 3 Dessaix, Robert (22 February 2008). "The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ↑ Penny, Laurie (5 September 2010). "Girls, tattoos and men who hate women". New Statesman. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Baski, Kurdo (31 July 2010). "How a brutal rape and a lifelong burden of guilt fuelled Girl with the Dragon Tattoo writer Stieg Larsson". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ↑ PRich, Nathaniel (5 January 2011). "The Mystery of the Dragon Tattoo: Stieg Larsson, the World's Bestselling — and Most Enigmatic — Author". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

- ↑ "The real-life Swedish murder that inspired Stieg Larsson". Telegraph.co.uk. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ "Where is Hedestad really located?". The web resource for information about Sweden. Go-to-Sweden.com. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Pettersson, Jan-Erik (2011-03-11). "The other side of Stieg Larsson". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ↑ McGrath, Charles (23 May 2010). "The Afterlife of Stieg Larsson". The New York Times Magazine.

- ↑ "Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy". The Guardian. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ MacDougal, Ian (27 February 2010). "The Man Who Blew Up the Welfare State". n+1. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- 1 2 3 Alm, Cecilia Ovesdotter; Stenport, Anna Westerstahl (Summer 2009). "Corporations, Crime, and Gender Construction in Stieg Larsson's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo: Exploring Twenty-First Century Neoliberalism in Swedish Culture". Scandinavian Studies. 81 (2): 157.

- ↑ Sampaio, Maria de Lurdes (June 30, 2011). "Millennium Trilogy: Eye for Eye and the Utopia of Order in Modern Waste Lands". Cross-Cultural Communication. 7 (2): 73.

- ↑ "2009 Galaxy British Book Awards. Winners. Shortlists. 1991 to present". Literaryawards.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ "Bouchercon World Mystery Convention: Anthony Awards and History". Bouchercon.info. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ "The Anthony Awards". Bookreporter.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ↑ Allen, Katie (6 October 2008). "Rankin and P D James pick up ITV3 awards". News. The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- ↑ Berenson, Alex (11 September 2008). "Stieg Larsson's The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- ↑ Miller, Marjorie (17 September 2008). "Thawing a cold case in Scandinavia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- ↑ Selman, Matt (20 February 2009). "Cold Noir". Time. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- ↑ Alleva, Richard (May 7, 2010). "Off the page: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo & Kick-Ass". Commonweal. New York City: Commonweal Foundation. 137 (9): 26.

- ↑ Daar, Abdallah (July 29, 2010). "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo". Nature. 466 (7306): 566. doi:10.1038/466563a.

- ↑ Helfand, Michael (September 21, 2008). "Posthumous Swedish Mystery One of Genre's Best". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. E-6.

- ↑ "Stieg Larsson Stats: By the Numbers". In the Bookroom. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ Bronson, Eric, ed. (2011). The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Philosophy. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0470947586.

- ↑ "James Bond to star in US Dragon Tattoo remake". BBC News. 27 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Barrett, Annie (16 August 2010). "'Dragon Tattoo' casts its Lisbeth Salander: Have you seen Rooney Mara in previous roles?". Popwatch.ew.com. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Dragon Tattoo Trilogy: Extended Edition.

- ↑ Ephron, Nora (5 July 2010). "The Girl who Fixed the Umlaut". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

Publication details

- August 2005, Swedish, Norstedts (ISBN 978-91-1-301408-1), paperback (poss 1st edition)

- 10 January 2008, UK, MacLehose Press, (Quercus Imprint) (ISBN 978-1-84724-253-2), hardback (trans as The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo by Reg Keeland)

- 16 September 2008, US, Alfred A. Knopf (ISBN 978-0-307-26975-1), hardback