Interlinear gloss

In linguistics and pedagogy, an interlinear gloss is a gloss (series of brief explanations, such as definitions or pronunciations) placed between lines (inter- + linear), such as between a line of original text and its translation into another language. When glossed, each line of the original text acquires one or more lines of transcription known as an interlinear text or interlinear glossed text (IGT)—interlinear for short. Such glosses help the reader follow the relationship between the source text and its translation, and the structure of the original language. In its simplest form, an interlinear gloss is simply a literal, word-for-word translation of the source text.

History

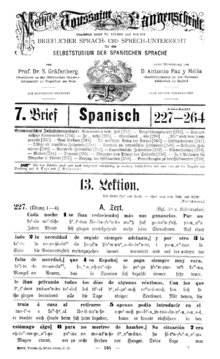

Interlinear glosses have been used for a variety of purposes over a long period of time. One common usage has been to annotate bilingual textbooks for language education. This sort of interlinearization serves to help make the meaning of a source text explicit without attempting to formally model the structural characteristics of the source language.

Such annotations have occasionally been expressed not through interlinear layout, but rather, through enumeration of words in the object and meta language. One such example is Wilhelm von Humboldt's annotation of Classical Nahuatl:

- ni-1 c-2 chihui3 -lia4 in5 no-6 piltzin7 ce8 calli9 ich1 mache3 es2 für4 der5 mein6 Sohn7 ein8 Haus9 [1]

This "inline" style allows examples to be included within the flow of text, and for the word order of the target language to be written in an order which approximates the target language syntax. (In the gloss here, mache es is reordered from the corresponding source order to approximate German syntax more naturally.) Even so, this approach requires the readers to "re-align" the correspondences between source and target forms.

More modern 19th and 20th-century approaches took to glossing vertically, aligning the same sort of word-by-word content in such a way that the metalanguage terms were placed vertically below the source language terms. In this style, the given example might be rendered thus (here English gloss):

ni- c- chihui -lia in no- piltzin ce calli I it make for to-the my son a house I made my son a house.

Note that here word ordering is determined by the syntax of the object language.

Finally, modern linguists have adopted the practice of using abbreviated grammatical category labels. A recent (2008) publication which repeats this example labels it as follows:[2]

ni-c-chihui-lia in no-piltzin ce calli 1SG.SUBJ-3SG.OBJ-mach-APPL DET 1SG.POSS-Sohn ein Haus

This approach is denser and also requires effort to read, but it is less reliant on the grammatical structure of the metalanguage for expressing the semantics of the target forms.

In computing, special text markers are provided in Specials (Unicode block) to indicate the start and end of interlinear glosses.

Structure

A semi-standardized set of parsing conventions and grammatical abbreviations is explained in the Leipzig Glossing Rules.[3]

An interlinear text will commonly consist of some or all of the following, usually in this order, from top to bottom:

- The original orthography (typically in italic or bold italic),

- a conventional transliteration into the Latin alphabet,

- a phonetic transcription,

- a morphophonemic transliteration,

- a word-by-word or morpheme-by-morpheme gloss, where morphemes within a word are separated by hyphens or other punctuation,

and finally

- a free translation, which may be placed in a separate paragraph or on the facing page if the structures of the languages are too different for it to follow the text line by line.

As an example, the following Taiwanese clause has been transcribed with five lines of text:

- the standard pe̍h-ōe-jī transliteration,

- a gloss using tone numbers for the surface tones,

- a gloss showing the underlying tones in citation form (before undergoing tone sandhi),

- a morpheme-by-morpheme gloss in English, and

- an English translation:[4]

1. goá iáu-boē koat-tēng tang-sî boeh tńg-khì. 2. goa1 iau1-boe3 koat2-teng3 tang7-si5 boeh2 tng1-khi3. 3. goa2 iau2-boe7 koat4-teng7 tang1-si5 boeh4 tng2-khi3. 4. I not-yet decide when want return. 5. "I have not yet decided when I shall return."

In linguistics, it has become standard to align the words and to gloss each transcribed morpheme separately. That is, koat-tēng in line 1 above would either require a hyphenated two-word gloss, or be transcribed without a hyphen, for example as koattēng. Grammatical terms are commonly abbreviated and printed in SMALL CAPITALS to keep them distinct from translations, especially when they are frequent or important for analysis. Varying levels of analysis may be detailed. For example, in a Lezgian text using standard romanization,[5]

Gila abur-u-n ferma hamišaluǧ güǧüna amuqʼ-da-č now they-OBL-GEN farm forever behind stay-FUT-NEG Now their farm will not stay behind forever.

Here every Lezgian morpheme is set off with hyphens and glossed separately. Since many of these are difficult to gloss in English, the roots are translated, but the grammatical suffixes are glossed with three-letter grammatical abbreviations.

The same text may be glossed at a different level of analysis:

Gila aburun ferma hamišaluǧ güǧüna amuqʼ-da-č now their.OBL farm forever behind stay-will-not Now their farm will not stay behind forever.

Here the Lezgian morphemes are translated into English as much as possible; only those which correspond to English are set off with hyphens.

A more colloquial gloss would be:

Gila aburun ferma hamišaluǧ güǧüna amuqʼdač now their farm forever behind won't.stay Now their farm will not stay behind forever.

Here the gloss is word for word; rather than setting off Lezgian morphemes with hyphens, the English words in the gloss are joined with periods when more than one is required to translate a Lezgian word.

Punctuation

In interlinear morphological glosses, various forms of punctuation separate the glosses. Typically, the words are aligned with their glosses; within words, a hyphen is used when a boundary is marked in both the text and its gloss, a period when a boundary appears in only one. That is, there should be the same number of words separated with spaces in the text and its gloss, as well as the same number of hyphenated morphemes within a word and its gloss. This is the basic system, and can be applied universally. For example,

- (Turkish) Odadan hızla çıktım.

oda-dan hız-la çık-tı-m room-ABL speed-COM go.out-PFV-1sg room-from speed-with go_out-perfective-I - 'I left the room quickly'

An underscore may be used instead of a period, as in go_out-PFV, when a single word in the source language happens to correspond to a phrase in the glossing language, though a period would still be used for other situations, such as Greek oikíais house.FEM.PL.DAT 'to the houses'.

However, sometimes finer distinctions may be made. For example, clitics may be separated with a double hyphen (or, for ease of typing, an equal sign) rather than a hyphen:

- (French) Je t'aime.

je꞊te꞊aime I꞊you꞊love - 'I love you'

Affixes which case discontinuity (infixes, circumfixes, transfixes, etc.) may be set off by angle brackets, and reduplication with tildes, rather than with hyphens:

- (Tagalog) sulat, susulat, sumulat, sumusulat (verbal declensions)

sulat su~sulat s⟨um⟩ulat s⟨um⟩u~sulat write contemplative mood~write ⟨agent trigger.past⟩write ⟨agent trigger⟩contemplative~write

(See affix for other examples.)

Morphemes which cannot be easily separated out, such as umlaut, may be marked with a backslash rather than a period:

- (German) unsern Vätern

unser-n Väter-n our-DAT.PL father\PL-DAT.PL - 'to our fathers' (the singular of Väter 'fathers' is Vater)

A few other conventions which are sometimes seen are illustrated in the Leipzig Glossing Rules.[3]

See also

- Kanbun – Japanese tradition of glossing Classical Chinese texts

- Ruby text – a gloss sometimes used with Chinese or Japanese to show the pronunciation

- Collection of texts in the EOPAS system, many in interlinear formats and linked back to the source media

References

- ↑ Lehmann, Christian (2004-01-23). "Directions for interlinear morphemic translations". In Geert Booij, Christian Lehmann, Joachim Mugdan, Stavros Skopeteas. Morphologie. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Flexion und Wortbildung. Handbücher der Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft. 2. Berlin: W. de Gruyter. pp. 1834–1857.

- ↑ Haspelmath, Martin (2008). Language typology and language universals: an international handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 715. ISBN 978-3-11-011423-2.

- 1 2 Bickel, Balthasar; Bernard Comrie; Martin Haspelmath (February 2008). "The Leipzig Glossing Rules. Conventions for Interlinear Morpheme by Morpheme Glosses.". Dept. of Linguistics – Resources – Glossing Rules. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Example from A Basic Vocabulary for a Beginner in Taiwanese by Ko Chek Hoan and Tan Pang Tin

- ↑ Haspelmath 1993:207

External links

- The Leipzig Glossing Rules: Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses

- Interlinear Glossed Text Standards (E-MELD)

- Interlinear Glossed Text Levels (E-MELD)

- Toward a General Model of Interlinear Text (E-MELD)

- Interlinear Morphemic Glosses

- Glossing Ancient Languages and Texts. A forum for recommendations on the Interlinar Morphemic Glossing of ancient languages as attested in ancient manuscripts.

- Online Interlinear of Biblical Greek Scriptures (New Testament) text - Requires Adobe Acrobat

- ODIN - The Online Database of INterlinear text