Golden Age of Mexican cinema

The Golden Age of Mexican cinema (in Spanish Época de Oro del Cine Mexicano) is a period in the history of the Cinema of Mexico between 1936 and 1959[1] when the Mexican film industry reached high levels of production, quality and economic success of its films, besides having gained recognition internationally. The Mexican film industry became the center of commercial films in Latin America.

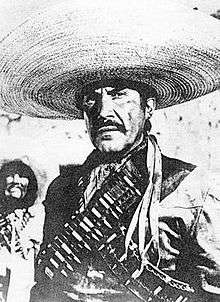

The Golden Age began symbolically with the film Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1935), directed by Fernando de Fuentes. In 1939, during World War II, the film industry in the US and Europe decline, because the materials previously destined for film production now were for the new arms industry. Many countries began to focus on making films about war, leaving the opportunity to Mexico, to produce commercial films for the Mexican and Latin American markets. This cultural environment favored the emergence of a new generation of directors and actors considered to date, icons in Mexico and in Hispanic countries and Spanish-speaking audiences.

Origins

In 1939 Europe and the United States they participated in the World War II, and the film industries of these regions were severely affected. Europe due to its location and the United States because the materials used to produce films (such as cellulose), became scarce and were rationed. In 1942, when German submarines destroyed a Mexican tanker, Mexico joined the Allies in the war against Germany. Mexico won the status of most favored nation. Thus, the Mexican film industry found new sources of materials and equipment and secured its position in the production of quality films worldwide. During World War II, the film industry in France, Italy, Spain, Argentina and the United States focused on war films, which made it possible the Mexican film industry, with much more versatile themes, became dominant in the markets of Mexico and Latin America.

Since the beginning of talkies in Mexico, some films (like Santa (1931), directed by Antonio Moreno and The Woman of the Port (1934), directed by Arcady Boytler, were a huge blockbuster that showed that Mexico had the equipment and talent needed to sustain a strong film industry. One of the first blockbusters was the film Allá en el Rancho Grande by Fernando de Fuentes, which became the first classic of Mexican cinema; this film is referred to as the initiator of the "Mexican film industry".[2]

In the early 1940s began the emergence of great Mexican film studios settled in Mexico City, they begin to support the mass production of films. Among the most important are CLASA Films, FILMEX, Films Mundiales, Cinematográfica Calderón, Películas Rodriguez and Producciones Mier y Brooks, among others.

The Golden Age

The Mexican cinema continued to perform works of superb quality and began to explore other genres like comedy, romance and musical. In 1943, the film Wild Flower, brought together a film team comprising the filmmaker Emilio Fernández, the photographer Gabriel Figueroa, the actor Pedro Armendariz and actress Dolores del Río. The films María Candelaria (1943) and The Pearl (1947), were considered works summit Fernandez and his team, and filled Mexican cinema enormous prestige, pacing worldwide in major film festivals. María Candelaria was awarded in 1946 with the Golden Palm in the Cannes Film Festival. The Pearl was awarded the Golden Globe of the American film industry, being the first Spanish film to receive such recognition.[3]

The Mexican cinema in its Golden Age, mimicked the Star System that prevailed in Hollywood. Thus, unlike other film industries in Mexican cinema began to develop the "cult of an star", a situation that led to the emergence of stars caused a sensation in the public and became real idols, in a way very similar to that of American film industry. However, unlike what happened in Hollywood, Mexican film studios never had total power over the big stars, and this allowed these shine independently and develop in a huge multitude of genres, mainly figures emerged in Mexican cinema in the early 1950s, much more versatile and complete than those of the previous decade.

Stars

Among the figures that reached the level of idols in the Mexican cinema, he emphasizes Pedro Infante. Trying to explain the phenomenon Pedro Infante is, at this point, a useless enterprise. His first films were not aimed toward creating a myth. The result of his meeting with the director Ismael Rodríguez in the film Nosotros los pobres (1947), served to consolidate the figure of Infante within the mythology of Mexican cinema. For many, Infante represented what every Mexican should be: a dutiful son,an unconditional friend, a romantic lover. In the extensive gallery of stars of Mexican cinema Pedro Infante is the only one who could unify public sentiment. His popularity has continued to grow as new generations are added. His figure remains the most important in Mexican cinema.[4]

Other of the early mass idols in Mexican cinema was Jorge Negrete. In addition to his role as an actor, Negrete was also a prominent singer and one of the leading representatives of Mexican ranchera music. Negrete was one of the highest grossing actors of Latin American Cinema during almost the entire decade of the 1940s. His premature death caused one of the first collective chaos in Mexico.

Maria Félix was an exceptional case in the Mexican Cinema. Woman of an stunning physical beauty and strong personality, which immediately dominated the roles of "femme fatale" in Mexican movies. Before the success of Maria Félix, the women were in supporting roles (self-sacrificing mothers, submissive girlfriends). Based on the success of Félix, more movies with female themes began to be realized. The film Doña Bárbara (1943), began the myth of Maria Felix as La Doña. The unique real personality of María merged with her filmic personality leading to one of the most fascinating myths of the seventh art. Her legend was forged without her moving a finger.[5] The imagination of the people did all the work.

Dolores del Rio at her best moments, represented one of the highest ideals of the Mexican female beauty. The myth of Dolores del Rio did not begin in Mexico, but in Hollywood, where the actress reached the status of "Diva" in the 1920s and 1930s, very difficult for an actress of Hispanic origin. After a more than worthy career in Hollywood, Dolores returned to Mexico, where she managed to maintain and even raise the prestige that her enjoyed in the American film industry, thanks to a series of films made especially for her, for her eternal admirer, the filmmaker Emilio Fernandez, where the strips away the stony image acquired in Hollywood and highlights her indigenous features. Films like Wild Flower and Maria Candelaria(1943), passed through the image of Mexico around the world, and Dolores del Río became a national symbol, after being, for many years, a symbol of "the Mexican" abroad.

One of the faces that captivate the audiences was Pedro Armendariz. Although his veins did not run a single drop of Indian blood, Armendariz managed to embody the Mexican essence better than any other actor in Mexico. This -shared appreciation for historians, critics, colleagues and admirers, is based significantly on the characters that the actor starred under the direction of Emilio Fernandez.[6] Later, Armendariz dabbled in Hollywood and some European countries.[7]

Arturo de Córdova was another prominent male figure of Mexican Cinema. His specialty were the roles of tormented men who often sank into madness. His good looks and contrived elegance made him famous. He was certainly one of the most requested heartbreakers by Hispanic women. Always surrounded himself with female beauty deals breathers, while his graying temples were becoming a personal and nontransferable brand.

Mario Moreno Cantinflas was a comedian and mime, who emerged from the popular theatres. He achieved great popularity in the cinema with his portrayal of the character Cantinflas, a charismatic poor man, a "friendly neighbor" with quite a peculiar speech. The character of Cantinflas was to Mario Moreno as The Tramp was to Charles Chaplin. But unlike Chaplin, Cantinflas based his character on joy, rather than melancholy. His characters were always exhilarating funny. Cantinflas enjoyed remarkable success.

Another successful star was the comedian Germán Valdés, "Tin Tan". He was a great versatile actor and excellent singer. He became famous portraying the character of the pachuco (cultural movement which emerged in Chicago during the twenties among the Hispanic community). His films were mainly based on parody and absurd situations, skilled musical numbers portraying visual mischief with an attractive female. "Tin Tan" had a huge cultural impact among some sectors of the Mexican public, and his films reached the status of cult films.[8]

Some other Mexican figures achieved recognition for foreign level. Katy Jurado became an important and sought after actress in the Hollywood films (primarily in the Western film ), achieving recognition as the Golden Globe (1952) and a nomination for Academy Award of the American Film Academy (1954).[9] Meanwhile, Silvia Pinal achieved recognition in the field of "art cinema", especially thanks to her collaborations with the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. The film Viridiana (1961), probably the most legendary film in the Buñuel's cinematography, was headlined by Pinal. Awarded with the Golden Palm of Cannes Film Festival, Viridiana captured Pinal in the history of world cinema. Beautiful, charismatic and endowed with a wonderful versatility, Pinal has enjoyed a successful career spanning several decades in the Mexican stardom.[10]

Sara García, called the "Mexico's Grandmother", deserves special mention. She was an outstanding actress possesses great versatility and a strong dramatic intensity. Her poignant or funny interpretations of old woman (grandmother, mothe, nana), converted her, similar to Cantinflas and Tin Tan, in part of Mexican popular culture, and her fame resists the passage of time.

Among the most prominent actresses in Mexican cinema in its heyday are Columba Dominguez, one of the main muses of filmmaker Emilio Fernandez. Endowed with a native strong appeal, she worked in leading internationally renowned bands such as Pueblerina (1949). Miroslava was a dazzling beauty of European origin who achieved glory in Mexican cinema between late 1940 and mid-1950, before dying tragically in 1955. Marga López was important and outstanding actress with a very broad acting rang. The dazzling Elsa Aguirre was one of the most important "femme fatales" of the Mexican film industry. Another important actress was Gloria Marín, who enjoyed a large sign in the early 1940s thanks in part to her famous teamed with Jorge Negrete in a series of romantic movies. María Elena Marqués was another important actress of an strong personality. Among the dazzling beauties flooded the Mexican screens are also Esther Fernández, Rosario Granados, Rosita Quintana, Rita Macedo, Emilia Guiú, Alma Rosa Aguirre or Lilia Prado, among many others.

The best actresses who shone in this period stands Carmen Montejo, an actress with an impeccable presence in film, theater and television. Meanwhile, Andrea Palma was considered the first "Diva" of Mexican Cinema, immortalized in the beginning of the Mexican film industry as The Woman of the Port, and later specialized in roles or sophisticated prostitute or elegant. Emma Roldán was one of the pioneers of the Mexican film industry with a career spanning more than a hundred films. Meanwhile Prudencia Grifell, a veteran revue star in the 1920's, was immortalized (with Sara García) in Granny roles in the films.

As Mexico was the main film industry in the Spanish-speaking countries, its industry attracted other important figures of other Hispanic film industries. The most important were the Spanish Sara Montiel, who achieved international renown after passing through the Mexican cinema in the first half of the 1950s, and Argentinean Libertad Lamarque, who after leaving her country in 1947 after an award-winning career in Argentine cinema, settled in Mexico, where she made most of her films and practically remained active for the rest of her life. From Spain also reach figures like Jorge Mistral, Armando Calvo or Lola Flores; from Argentina arrived Niní Marshall and Luis Aldás. From Cuba arrived René Cardona, Rita Montaner or Rosita Fornes, while Irasema Dilián was imported from Italian Cinema.

Among the actors highlights Ignacio López Tarso, one of the most versatile Latin American actors and a very prominent film, television and stage career. Lopez Tarso was the protagonist of Macario (1959), first Mexican film nominated for an Academy Award of the American Academy.[11] The Soler Brothers: Domingo, Andrés, Fernando and Julián Soler, were probably some of the Mexican actors with most movies in their careers. In a great variety of roles, both dramatic and comic, their histrionic talent prevailed in their films. David Silva reached an enormous popularity to embody the hero of lower-class neighborhood and in numerous films of social Film or urban cinema. Emilio Tuero was one of the first film heartthrobs massive success in the Mexican film industry in the early 1940s. Roberto Cañedo was an actor with a very long film career that spanned more than fifty years in film, theater and television. Fernando Fernandez besides being an outstanding singer, achieved enormous popularity in musical films incarnating roles of good and noble man.

Comedy

Many other comedians achieved consecration in Mexican cinema. From comic slapstick couples (in the style of Laurel and Hardy) to independent actors who achieved a huge poster. Many of these comedians emerged from the called Carpas or Mexican popular theaters. Joaquín Pardavé, was a popular actor who captivated with the same dramatic or comic characters. Pardavé was also a composer and film director, and his beginnings in the industry, from the Silent films, made him a "symbolic father" of all Mexican comedians from the thirties to the sixties.

Antonio Espino y Mora, better known as Clavillazo was another Mexican actors who began his careers in the Carpas. More than 30 films are his repertoire and is one of the most beloved and remembered artists. Another artist who started in the Carpas and also his sympathy, noted for his picturesque way of dancing was Adalberto Martínez "Resortes", who had a long career, then worked for over 70 years in film and television.

Gaspar Henaine and Marco Antonio Campos better known as "Viruta and Capulina" were a comic duo that were found in the form of white humor win the affection of the people. Viruta and Capulina began their career together in 1952, although individually had worked on other projects. They filmed more than 25 films.[12]

Although they do not have a large number of films together, Manuel Palacios "Manolín" and Estanislao Shilinsky Bachanska are remembered for their great chemistry in the theaters and later in the films.

Musical and Rumberas films

The Musical film genre in Mexico was strongly influenced by the Mexican folk music or Ranchero music. Stars as Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Luis Aguilar and Antonio Aguilar made dozens of musical films of these gender who served as a platform to promote Mexican music. The songs of important composers like Agustín Lara or José Alfredo Jiménez served as the basis for the arguments of many films. Libertad Lamarque also highlighted by her performances where music and songs were the main protagonists.

The tropical music that was popular in Mexico and Latin America since the 1930s, and was also reflected in Mexican cinema. Numerous music magazines were made in the 1940s and 1950s. In these productions it was common to see figures ranging from Damaso Perez Prado, Toña la Negra, Rita Montaner, María Victoria or Los Panchos. However, the musical film in Mexico was mostly represented by the so-called Rumberas film, a unique cinematic curiosity of Mexico, dedicated to the film exaltation of the figure of the "rumba" (dancers of Afro-Antillean rhythms). The main figures of this genre were Cubans María Antonieta Pons, Amalia Aguilar, Ninón Sevilla and Rosa Carmina and Mexican Meche Barba. Between 1938 and 1965 more than one hundred Rumberas films were made.

Film Noir

In Mexico, the Film Noir (very popular in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s) was represented by the actor and director Juan Orol. Inspired by the popular Gangster film and figures like Humphrey Bogart or Edward G. Robinson, Orol created a filmic universe and a particular style by mixing elements of classic Film noir, with Mexican folcklor, urban environments, cabaret and tropical music. Example, the classic film Gangsters Versus Cowboys (1948).

Horror films

Although the 1960s are considered the Golden Age of Horror and science fiction in Mexican cinema, during the Golden Age they were found some remarkable works. Chano Urueta, a prolific director who began in the silent era, had had their approaches with the supernatural in Desecration (1933) and The Sign of Death (1939), however his greatest contributions come with The Amazing Beast (1952), film that first introduced the wrestlers in the genre. Other works in the genre would La Bruja (1954), Ladrón de Cadáveres (1956), the trilogy El Jinete sin cabeza (1957), the terror western, The Baron of Terror (1962) and The Living Head(1963).

Fernando Mendez was the most prolific filmmaker in the Horror films of the era. His most successful film was El vampiro (1957), starring Germán Robles, lead actor of the genre for the next two decades. Another actors highlights of gender were Abel Salazar, Lorena Velázquez and Ariadne Welter.

Filmmakers

Among the major filmmakers who contributed to consolidate the Mexican cinema in its Golden Age include the following:

- Miguel Contreras Torres: Was one of the pioneers of Mexican cinema, where he started working in 1926. The only Mexican director who managed to make the transition from silent to talkies. The complete filmography of Contreras Torres speaks of a man interested in exalting nationalism and patriotism, from cinema. In essence, they are basically three thematic lines that built his career: national history, religious themes and manners. Although not the only, indeed, in the Mexican case, Contreras Torres which penetrates with greater emphasis on the exaltation of the historical facts of his country. The filmography of Miguel Contreras Torres, in this brief and incomplete review, spanned more than 45 years in which he participated in more than 50 films.[13]

- Fernando de Fuentes: Pioneer of talkies and director of three classic Mexican films: El compadre Mendoza (1933), Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1936) and Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936), Fernando de Fuentes is one of the most famous and least understood figures of Mexican film industry. Comments about his career almost always point out as an author who decided to stop being to become an efficient producer of grossing films, his films artificially dividing into two periods characterized by the presence or absence of aesthetic pretensions. Vámonos con Pancho Villa his masterpiece, was misunderstood for decades. The film was released three months after Allá en el Rancho Grande and only stayed one week in theaters. Success and failure occurred at the same time. Fernando de Fuentes was actually the first Mexican director who understood the nature of talkies and successfully took advantage of all the possibilities of this medium.[14]

- Alejandro Galindo: During the Golden Age, the rising urban Mexico had in Alejandro Galindo one of its most faithful film chroniclers. Possessing a special talent to recreate the behaviors and the popular speech of the Mexico City, Galindo was a director capable of creating his own universe from characters and situations representative of modern Mexico. From Campeón sin corona (1945) Alejandro Galindo initiated the most important stage of his career, in which the actor David Silva was instrumental. Boxers, taxi drivers, bus drivers from vendors vacuum cleaners, the new Mexican middle class was found on the screen known characters in their environment. Una familia de tantas (1948) represented the peak of this period in which Galindo creative genius combined with a successful business sense.[15]

- Emilio Fernández: One of the most important, influential and recognized filmmakers in this stage of Mexican cinema. Emilio was the creator of a Mexican film folk and indigenous type that contributed to the cultural and artistic discovery that Mexico lived in the 1940s, possessing an impeccable and unique aesthetic (achieved largely thanks to his principal photographer Gabriel Figueroa). Emilio Fernández bequeathed a filmography totaling around 129 jobs, countless beautiful images, hundreds of evocations of a Mexico that was planned, customs and identity, defended at all costs. A path that was recognized on several occasions with Silver Ariel, the Colón de Oro in Huelva, Spain, and a chair with his name on the Moscow Film School, among many other international awards. Emilio Fernandez was not only known for his visceral character, but also to achieve integration of a film crew that caught the attention of Hollywood and Europe. Gabriel Figueroa as a photographer, Mauricio Magdaleno as a screenwriter and the actors Pedro Armendariz, Dolores del Río, Columba Domínguez and María Félix, directed several productions who they promoted customs and national values associated to the Mexican Revolution.

- Roberto Gavaldón: Roberto Gavaldón represents one of the most extraordinary cases of ambivalent appreciation that recorded the history of Mexican cinema. His admirers include the refined quality of his images, his impeccable handling the camera and his inclination towards dark themes and tormented characters. The same characteristics have been identified as defects by critics, who consider Gavaldón as a technically correct academic filmmaker, cold and even narcissistic, but lacking authenticity. During the Golden Age, Roberto Gavaldón was recognized for his technical and artistic qualities. His habit of retakes to achieve the effect or nuance of performance that brought him fame wanted obsessive and perfectionist. Dry and authoritarian character, Gavaldón imposed a strict code of behavior on film sets, reason why some technicians and actors referred to him with the descriptive nickname "The Ogre". However, the antipathies that awoke his character were offset by admiration and respect for his work. Gavaldón films were synonymous with quality and working with him was considered a true honor.[16]

- Ismael Rodríguez: Restless, imaginative, bold and possessing a unique flair for the blockbuster, Ismael Rodriguez was indisputably the director of the Mexican people. With his brothers (Joselito and Roberto), founded Películas Rodríguez producer of long and successful career. Popular filmmaker par excellence among his merits is having taken advantage of the histrionic possibilities of Pedro Infante, actor who directed sixteen times, including the ranchera comedy Los tres García (1946) and urban melodramas Nosotros los pobres (1947), Ustedes los ricos (1948) and Pepe el Toro (1952), trilogy that reached the category of myth. In addition to various national and international awards, Ismael Rodriguez received a 1992 Golden Ariel for the significance of his work.[17]

- Julio Bracho: Common way place to define Julio Bracho ambiguous is to identify it as the most intellectual film director of "Golden Age". While it is not easy to agree with the connotation that you want to give to the word "intellectual" when talking about Julio Bracho, it is possible to accept that it was one of the most important directors of Mexican cinema in the forties and fifties, with several interesting films and some of them worthy of being mentioned among the best of Mexican cinema. His wide culture and fine sensibility, give another dimension to melodrama in film.[18]

- Luis Buñuel: The so-called "Father of Surrealist Cinema" made in Mexico most of his extensive filmography, and contributed greatly to the rise of Mexican cinema in the second stage of its Golden Age, in the 1950s. The film Los Olvidados (1950) achieved an enormous impact around the world, the extent of being considered by the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site. One of his last films in Mexico, before moving to Europe was the Spanish-Mexican co-production Viridiana (1961), which was presented to contest Cannes Film Festival as an official representative of Spain and won the Palme d'Or. However, after the newspaper Vatican L'Osservatore Romano condemned the film, which was attacked as blasphemous and sacrilegious, Viridiana could not be project officially in Spain until 1977.

- Juan Orol: He was known as the "King of Mexican Gangster films". He is also known as the "Involuntary surrealIST". Pioneer of the Mexican talkies and one of the main promoters of called Rumberas film. Family melodramas to rumberas and gangsters movies, the Orol's film universe is surreal and full of flaws in some sense; why his films have been described as a Cult films. That has given his films an important place in Mexican cinema.

Decline

The first transmissions of the Mexican television started in 1950. In a few years, the television reached enormous power to reach the public. By 1956, the TV antennas were common in Mexican homes, and new media grew rapidly in the province. The first black and white television pictures appeared in a very small and oval screen, and thus the image was quite imperfect as they did not have the clarity and sharpness of the actual film image. However, not only in Mexico but throughout the world, the filmmakers immediately resented competition from this new media. This competition decisively influenced the history of cinema forcing the film industry to seek new ways both in the art itself, as in the treatment of subjects and genres.

The technical innovations came from Hollywood. Wide screens, three-dimensional cinema, color improvement and stereo sound were some of the innovations introduced by the American cinema during the early 1950s. At the time, the high cost of these technologies made it difficult for Mexico to compete; therefore, not for some years was it able to produce films incorporating these innovations.

On April 15, 1957, the whole country mourned with the news of the death of Pedro Infante. His death also marked the end of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema.

The world was changing and so was the way film was produced by other countries. The elimination of censorship in the United States allowed a more bold and realistic treatment of many topics. In France, a young generation of filmmakers educated in film criticism began the New Wave movement. In Italy, the Neorealism had claimed the careers of several filmmakers. The Swedish film with Ingmar Bergman made his appearance, while in Japan Akira Kurosawa appeared.

Meanwhile, Mexican cinema had been stalled by bureaucracy and difficulties with the union. Film production was now concentrated in a few hands, and the ability to see new filmmakers emerge was almost impossible due to the impositions of the directors of the Union of Workers of the Cinematographic Production (STPC). Three of the most important film studios disappeared between 1957 and 1958: Tepeyac, Clasa Films and Azteca.

Also in 1958, the Mexican Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences decided to discontinue the Ceremony of the Ariel Award recognizing the best productions of the national cinema. The Ariel was instituted in 1946 and emphasized the thriving state of the industry.

Principal films

1930s

- Santa (1931)

- ¡Que viva México! (1932)

- La Mujer del Puerto (1934)

- Redes (1934)

- Janitzio (1934)

- Dos Monjes (1934)

- Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936)

- Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1936)

- Águila o sol (1937)

- La mujer de nadie (1937)

- The Blood Stain (1937)

- La Zandunga (1938)

- Siboney (1938)

- Los de Abajo (1939)

- La Noche de los Mayas (1939)

1940s

- Ahí está el detalle (1940)

- Cuando los hijos se van (1941)

- La isla de la Pasión (Clipperton) (1941)

- El baisano Jalil (1942)

- Historia de un gran amor (1942)

- El Conde de Montecristo (1942)

- La Vírgen que forjó una patria (1942)

- Una carta de amor (1943)

- Distinto amanecer (1943)

- Doña Bárbara (1943)

- Flor silvestre (1943)

- Maria Candelaria (1943)

- México de mis recuerdos (1943)

- Santa (1943)

- Las Abandonadas (1944)

- Bugambilia (1944)

- Naná (1944)

- Campeón sin corona (1945)

- Pepita Jiménez (1945)

- El monje blanco (1945)

- Enamorada (1946)

- La Otra (1946)

- Gran Casino (1946)

- La otra (1946)

- La Barraca (1946)

- El sexo fuerte

- Los tres García (1946)

- Humo en los ojos (1946)

- La reina del trópico (1946)

- Pervertída (1946)

- Una mujer de Oriente (1946)

- La diosa arrodillada (1947)

- La perla (1947)

- Músico, poeta y loco (1947)

- En tiempos de la Inquisición (1947)

- El conquistador (1947)

- El niño perdido (1947)

- Nosotros los pobres (1947)

- Río Escondido (1947)

- Ustedes los ricos (1948)

- Gangsters Versus Cowboys (1948)

- Calabacitas tiernas (1948)

- Esquina bajan...! (1948)

- Una familia de tantas (1948)

- Angelitos negros (1948)

- Lola Casanova (1948)

- Maclovia (1948)

- Pueblerina (1948)

- Salón México (1948)

- Los tres huastecos (1948)

- Aventurera (1949)

- Doña Diabla (1949)

- Duelo en las montañas (1949)

- Calabacitas Tiernas (1949)

- El gran calavera (1949)

- La Malquerida (1949)

- La negra Angustias (1949)

- La oveja negra (1949)

- No desearás la mujer de tu hijo (1949)

- El rey del barrio (1949)

1950s

- ¡Ay amor... cómo me has puesto! (1950)

- El Ciclón del Caríbe (1950)

- En la palma de tu mano (1950)

- La marca del zorrillo (1950)

- Los olvidados (1950)

- Rosauro Castro (1950)

- Sensualidad (1950)

- Siempre tuya (1950)

- Simbad el mareado (1950)

- El suavecito (1950)

- Susana (Carne y demonio) (1950)

- Víctimas del pecado (1950)

- A. T. M. A toda máquina! (1951)

- ¿Que Te Ha Dado Esa Mujer? (1951)

- El ceniciento (1951)

- Doña Perfecta (1951)

- Chucho el Remendado (1951)

- Cuando levanta la niebla (1951)

- La hija del engaño (1951)

- Una mujer sin amor (1951)

- Mujeres sin mañana (1951)

- La noche avanza (1951)

- El revoltoso (1951)

- La Estatua de Carne (1951)

- Subida al cielo (1951)

- Trotacalles (1951)

- El bello durmiente (1952)

- El bruto (1952)

- Pepe el Toro (1952)

- Dos tipos de cuidado (1952)

- Él (1952)

- Me traes de un ala (1952)

- Camelia (1952)

- Sandra, la mujer de fuego (1952)

- El rebozo de Soledad (1952)

- Robinson Crusoe (1952)

- pernt tyrnt (1953)

- La ilusión viaja en tranvía (1953)

- El mariachi desconocido (1953)

- Raíces (1953)

- Mis Tres Viudas Alegres (1953)

- El Niño y la Niebla (1953)

- El rapto (1953)

- Reportaje (1953)

- Tehuantepec (1953)

- Escuela de vagabundos (1954)

- Maldita Ciudad (1954)

- El Casto Susano (1954)

- Abismos de Pasión (1954)

- El vizconde de Montecristo (1954)

- Un extraño en la escalera (1955)

- Ensayo de un crimen (1955)

- Historia de un abrigo de mink (1955)

- El inocente (1955)

- La Escondida (1955)

- Lo que le pasó a Sansón (1955)

- El médico de las locas (1955)

- ¡Qué bravas son las costeñas! (1955)

- El gato sin botas (1956)

- Ladrón de cadáveres (1956)

- La muerte en este jardín (1956)

- Torero (1956)

- Pablo y Carolina (1957)

- El vampiro (1957)

- Tizoc (1957)

- El Rio y la Muerte (1957)

- Yambao (1957)

- Nazarín (1958)

- La Estrella Vacia (1958)

- Macario (1959)

- La Cucaracha (1959)

- Las señoritas Vivanco

- Yo... el aventurero (1959)

- Dos Corazones y un Cielo (1959)

People

Actors

- Rodolfo Acosta

- Amalia Aguilar

- Antonio Aguilar

- Luis Aguilar

- Alma Rosa Aguirre

- Beatriz Aguirre

- Elsa Aguirre

- Luis Aldás

- Ernesto Alonso

- Sofía Álvarez

- Raúl de Anda

- Pedro Armendáriz

- Ramón Armengod

- Amparo Arozamena

- Eduardo Arozamena

- Antonio Badú

- Rafael Banquells

- Meche Barba

- Anita Blanch

- Armando Calvo

- Dolores Camarillo

- Roberto Cañedo

- Fernando Casanova

- Marcelo Chávez

- Roberto Cobo

- Joaquín Cordero

- Isabela Corona

- Mapy Cortés

- Rosa de Castilla

- Arturo de Córdova

- Amanda del Llano

- Dolores del Río

- Lilia del Valle

- Mimí Derba

- Silvia Derbez

- Irasema Dilián

- Columba Domínguez

- Irma Dorantes

- Evangelina Elizondo

- Antonio Espino "Clavillazo"

- Manolo Fábregas

- María Félix

- Emilio Fernández

- Fernando Fernández

- Freddy Fernández

- Esther Fernández

- Flor Silvestre

- Rosita Fornés

- Consuelo Frank

- Ángel Garasa

- Sara García

- Ramón Gay

- Carmelita González[19]

- Eulalio González "Piporro"

- Rosario Granados

- Maruja Grifell

- Prudencia Grifell

- Emilia Guiú

- Tito Guízar

- Anabel Gutiérrez

- Miguel Inclán

- Stella Inda

- Pedro Infante

- Rebeca Iturbide

- Tito Junco

- Víctor Junco

- Katy Jurado

- Famie Kaufman "Vitola"

- Libertad Lamarque

- Ana Bertha Lepe

- Marga López

- Carlos López Moctezuma

- Ignacio López Tarso

- Rita Macedo

- Delia Magaña

- María Victoria

- Gloria Marín

- María Elena Marqués

- Adalberto Martínez "Resortes"

- Arturo Martínez

- Jorge Martínez de Hoyos

- Manuel Medel

- Lilia Michel

- Miroslava

- Jorge Mistral

- Jose Mojica

- Carmen Molina

- Ricardo Montalbán

- Carmen Montejo

- Yolanda Montes "Tongolele"

- Sara Montiel

- Mario Moreno "Cantinflas"

- Evita Muñoz "Chachita"

- Jorge Negrete

- Eduardo Noriega

- Ramón Novarro

- Juan Orol

- Andrea Palma

- Leticia Palma

- Joaquín Pardavé

- Víctor Parra

- Blanca Estela Pavón

- Ana Luisa Peluffo

- Silvia Pinal

- María Antonieta Pons

- Lilia Prado

- Chula Prieto

- Rosita Quintana

- Enrique Rambal

- Gustavo Rojo

- Rubén Rojo

- Gilbert Roland

- Emma Roldán

- Rosa Carmina

- Martha Roth

- Wolf Ruvinskis

- Abel Salazar

- Lina Salomé

- Manolita Saval

- Fanny Schiller

- Ninón Sevilla

- Estanislao Shilinsky Bachanska

- David Silva

- Armando Silvestre

- Andrés Soler

- Domingo Soler

- Fernando Soler

- Julián Soler

- Fernando Soto "Mantequilla"

- Arturo Soto Rangel

- Su Muy Key

- Lupita Tovar

- Emilio Tuero

- Germán Valdés "Tin Tan"

- Yolanda Varela

- Lupe Vélez

- Julio Villarreal

- Ariadne Welter

- María Luisa Zea

Cinematographers

Filmmakers

Screenwriters

- Luis Alcoriza

- Arcady Boytler

- Luis Buñuel

- Juan Bustillo Oro

- Humberto Gómez Landero

- Antonio Guzmán Aguilera

- Mauricio Magdaleno

Studios

- Águila Films

- Azteca Films

- España Sono Films

- Estudios Camus

- Estudios Churubusco

- Estudios Tepeyac

- Cima Films S. A.

- Clasa Films

- Diana Films S. A.

- FILMEX

- Films Mundiales

- Grovas Films

- Oro Films

- Cinematográfica Calderón

- Mier y Brooks

- Películas Rodríguez

- Pereda films

See also

Further reading

- GARCÍA RIERA, Emilio (1986) Época de oro del cine mexicano Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) ISBN 968-29-0941-4

- GARCÍA RIERA, Emilio (1992–97) Historia documental del cine mexicano Universidad de Guadalajara, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (CONACULTA), Secretaría de Cultura del Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco y el Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía (IMCINE) ISBN 968-895-343-1

- GARCÍA, Gustavo y AVIÑA, Rafael (1993) Época de oro del cine mexicano ed. Clío ISBN 968-6932-68-2

- PARANAGUÁ, Paulo Antonio (1995) Mexican Cinema British Film Institute (BFI) Publishing en asociación con el Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía (IMCINE) y el Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (CONACULTA) ISBN 0-85170-515-4

- HERSHFIELD, Joanne (1996) Mexican Cinema, Mexican Woman (1940-1950) University of Arizona Press ISBN 0-8165-1636-7

- DÁVALOS OROZCO, Federico (1996). Albores del Cine Mexicano (Beginning of the Mexican Cinema). Clío. ISBN 968-6932-45-3.

- AYALA BLANCO, Jorge (1997) La aventura del cine mexicano: En la época de oro y después ed. Grijalba ISBN 970-05-0376-3

- MACIEL, David R. Mexico's Cinema: A Century of Film and Filmmakers, Wilmington, Delaware: SR Books, 1999. ISBN 0-8420-2682-7

- AGRASÁNCHEZ JR., Rogelio (2001). Bellezas del cine mexicano/Beauties of Mexican Cinema. Archivo Fílmico Agrasánchez. ISBN 968-5077-11-8.

- MORA, Carl J. Mexican Cinema: Reflections of a Society, 1896–2004, Berkeley: University of California Press, 3rd edition 2005. ISBN 0-7864-2083-9

- NOBLE, Andrea, Mexican National Cinema, Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-415-23010-1

- AGRASÁNCHEZ JR.., Rogelio (2006). Mexican Movies in the United States. McFarland & Company Inc. ISBN 0-7864-2545-8.

References

- ↑ "Por Fin: La Epoca de Oro 1936-1959". http://cinemexicano.mty.itesm.mx. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ↑ Mouesca, Jacqueline (2001). Erase una vez el cine: diccionario-- realizadores, actrices, actores, películas, capítulos del cine mundial y latinoamericano. México: Lom Ediciones. p. 390. ISBN 978-956-2823-364.

- ↑ Baugh, Scott L. (2012). Latino American Cinema: An Encyclopedia of Movies, Stars, Concepts, and Trends. United States: ABC-CLIO. p. 313. ISBN 978-031-3380-365.

- ↑ Mexican Cinema Stars: Pedro Infante

- ↑ Félix, María (1993). Todas mis guerras. México: Clío. p. 27. ISBN 968-6932-05-4.

- ↑ Mexican Cinema Stars: Pedro Armendáriz

- ↑ Galindo, Jorge Luis (2003). El Cine Mexicano En La Novela Mexicana Reciente (1967-1990). México: Editorial Pliegos. p. 191. ISBN 978-849-6045-125.

- ↑ ElInformador.com: Tin Tan, The Legend and the Man

- ↑ BuscaBiografías: Katy Jurado

- ↑ Mexican Cinema Stars: Silvia Pinal

- ↑ Películas del Cine Mexicano: Macario

- ↑ MMStudio:10 Greatests Mexican Comedians

- ↑ EcuRed: Miguel Contreras Torres

- ↑ Mexican filmmakers: Fernando de Fuentes

- ↑ Mexican filmmakers: Alejandro Galindo

- ↑ Mexican filmmakers: Roberto Gavaldón

- ↑ Mexican filmmakers: Ismael Rodríguez

- ↑ CineForever.com: Don Julio Bracho, The Intellectual Filmmaker of the Mexican Cinema

- ↑ "Muere la actriz Carmelita González". El Universal. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

External links

- 10 Best Mexican Movies in IMDB.com

- More of 100 Years of Mexican Cinema en el sitio del ITESM.

- Cineteca Nacional del Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes de México (Conaculta)

- Mexican Cinema