Golden Arrow (car)

| Golden Arrow | |

|---|---|

|

The Irving-Napier Golden Arrow at the National Motor Museum, Beaulieu | |

| Overview | |

| Production | one-off (1928) |

| Designer | John Samuel Irving (1880-1953) |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | front-engined land speed record car. |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine |

925 hp, 23.9 litre naturally aspirated Napier Lion W12 aero engine, ice cooling, no radiator |

| Transmission | 3-speed, final drive through twin driveshafts running either side of driver |

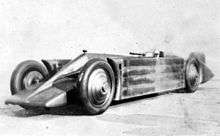

Golden Arrow was a land speed record racer built in Britain to regain the world land speed record from USA. Henry Segrave drove the car at Daytona Beach and exceeded the previous record by 24 mph or 39 kph.

The car

Built for ex-Sunbeam racing driver Major Henry Segrave to take the Land Speed Record from Ray Keech, Golden Arrow was one of the first streamlined land speed racers, with a pointed nose and tight cowling. Power was provided by a 23.9 litre (1462 ci) W12 Napier Lion VIIA aeroengine,[1] specially prepared by Napiers, designed for the Supermarine aircraft competing in the Schneider Trophy, producing 925 hp (690 kW) at 3300 rpm.[2]

The car was designed by ex-Sunbeam engineer, aero-engine designer and racing manager Captain John Samuel Irving (1880-1953).[3] It featured ice chests in the sides through which coolant ran and a telescopic sight on the cowl to help avoid running diagonally. The Rootes brothers, friends of Segrave and Irving, provided the Irving-designed individual aluminium body panels from Thrupp and Maberly.[1]

In March 1929, Segrave went to Daytona, and after a sole practice run, on 11 March, in front of 120,000 spectators,[2] set a new flying mile at 231.45 mph (372.46 km/h), easily beating Keech's old speed of 207.55 mph (334.00 km/h). Two days later, Lee Bible's White Triplex crashed and killed a photographer.

Daytona Beach was closed and Segrave was unable to make further runs to achieve the planned higher speeds.

Segrave was killed attempting a water speed record the next year. Golden Arrow never ran again.

Irving

Contemporary reports refer to the car as the Irving-Napier Golden Arrow.[4]

He had left Sunbeam and Irving's new employers, Humfrey-Sandberg, granted him permission to use part of his time designing and constructing Golden Arrow for ex-Sunbeam driver Henry Segrave. Golden Arrow was, Segrave said, very docile compared with other cars of its kind.[5] After the first trial run when he established no goggles were necessary at 182 mph Segrave drove the car up some planks to get it off the beach then drove it back along the main street of Daytona to its garage.[5]

_National_Motor_Museum%2C_Beaulieu.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

The sponsors required a British brand name for the engine and Napier was chosen. Dunlop's tyres were not warranted safe beyond 250 mph so the planned maximum of 274 mph was pulled back. To minimise frontal area Irving based the shape of the nose on the racing Supermarine S.5's cowling. Leading fairings in front of the front wheels gave no useful improvement and they were abandoned. An irreducible minimum was arrived at for the size of the cockpit because it had to be large enough for a sixteen-inch steering wheel believed to be needed to give sufficient leverage. In the end a large tail fin was adopted in case of side gusts, it located the centre of gravity an inch in front of the centre of pressure. The whole shell was shaped to exert a downward air pressure to keep the driving wheels on the ground and assist stability but a further 260 lbs of lead ballast was added to the tail. The twin prop-shafts were given strong casings in case they came apart at high speed. The axle was given no differential. At that time the car was notable among land speed record cars for having 4-wheel brakes. Suspension was by half-elliptic leaf springs all round, axle travel was limited to just 1¼ inches in front and 1¾ at the rear axle. The car was built at KLG Works on Kingston Hill.[5]

Segrave found he could not use all the throttle opening until past 2400 rpm, or, in bottom gear, until the car was moving in excess of 55 mph. The engine ran throughout without a misfire and the extra ice cube calling turned out to be unnecessary. Segrave made just the two runs. Including that first test run it is doubtful if the car has travelled as much as 40 miles in its whole life.[5]

Irving was helped by chief draughtsman W U Snell, his brother lent by Alvis to supervise the car's building and his daughter who dealt with all the associated progress-chasing and administrative work.[5]

The engine cannot be run again because the cylinder blocks were not properly inhibited and are now too porous. Wakefield / Castrol presented the car to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu in 1958.[5]

Backers

- Sir Charles Wakefield (Castrol)[6]

- O J S Piper, Portland (Red Triangle) Cement (Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers)[4][5]

- H O D Segrave (the driver)[6]

Suppliers

- Engine - Napier & Son, Acton

- Body - Thrupp & Maberly, Rootes brothers

- Assembly - Robinhood Engineering Works, Newlands, Putney Vale

- Spark plugs - KLG

- Steering - Marles

- Chassis frame - John Thompson (Wolverhampton)

- Shock absorbers - T B Andre, London

- Ball bearings - Ransome & Marles

- Cardan shafts - Hardy Spicer

- Gearbox - Gillett Stephen and Co, Bookham

- Brake operation - Clayton Dewandre, Lincoln

- Radiators - Gloucester Aircraft

- Special steels - Vickers Armstrong

- Fuel - British Petroleum

- Oil - C. C. Wakefield & Co[6]

References

- "Golden Arrow, between earlier and later land speed record cars at Beaulieu". twopsgoss. External link in

|publisher=(help)[7]

- 1 2 "Golden Arrow". World of Automobiles. Volume 7. London: Orbis Publishing Ltd. 1974. p. 799.

- 1 2 Tom Northey. (1974). "Land Speed Record". World Of Automobiles. Volume 10. London: Orbis Publishing Ltd. pp. 1161–66.

- ↑ Captain J. S. Irving. The Times, Tuesday, Mar 31, 1953; pg. 8; Issue 52584.

- 1 2 Interview: Captain J. S. Irving, designer of the Irving-Napier Special. Motor Sport, page 7 May 1929

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The inside story of the Irving-Napier Golden Arrow. Motor Sport, page 56 July 1981

- 1 2 3 John Bullock, The Rootes Brothers, Patrick Stephens, Sparkford Somerset ISBN 1852604549

- ↑ "National Motor Museum collection". National Motor Museum.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Golden Arrow (land speed racer). |

- "Fastest Thing On Wheels", June 1929, Popular Science

- Eric Dymock, Robert Horne's Golden Dream, Extracted from Sunday Times Supplement May 1990

- National Motor Museum website