Great Syrian Revolt

| Great Syrian Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Shaykh Hilal al-Atrash, rebel celebration in Hauran, 14 August 1925 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Syrian rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Sultan Pasha al-Atrash Fawzi al-Qawuqji Hasan al-Kharrat † Said al-As Izz al-Din al-Halabi Nasib al-Bakri Muhammad al-Ashmar Ramadan al-Shallash | ||||||

The Great Syrian Revolt (Arabic: الثورة السورية الكبرى) or Great Druze Revolt (1925–1927) was a general uprising across Mandatory Syria and Lebanon aimed at getting rid of the French, who had been in control of the region since the end of World War I.[1] The uprising was not centrally coordinated; rather, it was attempted by multiple factions – among them Sunni, Druze, Alawite, Christian, and Shia – with the common goal of ending French rule. The revolt was ultimately put down by French forces.

Background

In 1918, towards the end of World War I, the Ottoman Empire's forces withdrew from Syria after being defeated by the Allied Powers (Great Britain and France) and their Hashemite Arab allies from the Hejaz. The British had promised the Hashemites control over a united Arab state consisting of the bulk of Arabic-speaking lands from which the Ottomans withdrew, even as the Allies made other plans for the region in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement.

The idea of Syrian and Arab independence were not entirely new concepts.[2] French forces entering Syria faced resistance from local actors in the north in 1919, with the prominent Alawite sheikh Saleh al-Ali launching a revolt in the coastal mountain range and Ibrahim Hananu leading a revolt in Aleppo and the surrounding countryside. The leaders of both uprisings were vocally supportive of the creation of a united Syrian state presided over by Emir Faisal, the son of Sharif Husayn.[3] In March 1920 the Hashemites officially established the Kingdom of Syria with Faisal as king and the capital in Damascus.

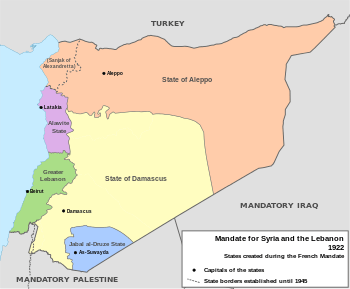

In the April 1920 San Remo Conference, the Allies were granted control over the Ottoman Empire's former Arab territories by the newly formed League of Nations, with Britain taking control of Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq, while France took control of Syria. This transfer of authority from the Ottomans to the French was generally to the consternation of Greater Syria's inhabitants, with the exception of some of the local Christian communities, particularly the Maronites of Mount Lebanon.[4] The brief Franco-Syrian War saw the Hashemites' pan-Arab forces defeated by the French in the Battle of Maysalun on 23 July, and the kingdom dissolved. France then divided the country into several autonomous entities: State of Damascus, State of Aleppo, Greater Lebanon, Alawite State and Jabal Druze State.[5] But many nationalists remained in Syria, advocating for independence. Even Britain felt unhappy when France claimed Lebanon and Syria as "colonies".[2]

Causes

Alienation of the elite

One major reason behind the outbreak of the Great Syrian Revolt was the French relationship with the local elites.[1] The Ottoman Empire, especially in its final centuries, had allowed much authority to devolve to the local level with many day-to-day administrative functions carried out by local notables. The Ottoman millet system allowed local peoples of different religious affiliations to uphold their own legal standards (for example, sharia law applying to Muslims, but not Jews, Catholics, or Orthodox Christians).

The European powers, however, had little grasp of the intricacies of Ottoman government, and failed to recognize that the disappearance of national authority did not mean that administration ceased to exist on a local level.[1] In the Mandate of Syria, the French assumed that the Syrians were incapable of practicing self-government, and so instituted a system which ostensibly served to train Syrians in that responsibility. French administrators were assigned to all levels of government, and their role was, officially, to train Syrian counterparts in that particular function.

The reality of the situation was very different. Instead of teaching, the advisors performed the functions of that office.[6] The effect was local rulers who resented being treated as if they did not know how to perform the functions they had been performing for centuries and who opposed this usurpation of their power. Further, authority had traditionally resided in the hands of a few families, while European administrators abandoned the systems of caste and class, undermining this elite by opening up offices to the general public.

Loyalty of tribes

Outside of cities, the French were not entirely successful in winning over nomadic populations, many of whom raised the standard of revolt in 1925.[7] The Ottoman Empire had initiated the process of tribal sedentarization, but it was not until the French Mandate of Syria that tribes began to lose their nomadic lifestyle.

After World War I, the territory that tribes wandered was divided between Turkey, the Mandate of Syria, and the Mandate of Mesopotamia, each controlled by different powers, thereby limiting their freedom of movement. In Syria, the process of industrialization was swift; roads were quickly built, cars and buses became commonplace. The situation for nomads was exacerbated by an influx of Armenians and Kurds from the new country of Turkey, who settled in the Mandate’s northern regions.

To pacify, or at least control, the tribes, the French instituted several restrictive measures; for example, tribes could not carry arms in settled areas, and had to pay lump taxes on livestock.[8] Additionally, the French attempted to bribe tribal leaders; but while this worked in some cases, it caused resentment in others. When the Great Syrian Revolt broke out in 1925, thousands of tribesmen were eager to fight against the French.

Nationalist sentiment

Syrian nationalism was fostered in Faisal’s short-lived kingdom, but after its dissolution many nationalists affiliated with his government fled the country to avoid death sentences, arrest and harassment by the French. Some went to Amman, where they found Amir Abdullah sympathetic to their cause; but under increasing pressure from the British, the young Abdullah drove them from Transjordan. These rejoined other Syrian nationalists at Cairo In 1921, when the Syrian-Palestinian Congress was founded.[2]

In 1925, in preparation for upcoming elections, high commissioner General Maurice Sarrail allowed the organization of political parties. The Syrian-Palestinian Congress had proved itself an ineffectual body, and its Syrian factions returned to Syria. They founded the People’s Party in Damascus, which was characterized by an intelligentsia leadership antagonistic toward local elites, with no social or economic programs, with support organized around individuals. Though unprepared for and not expecting an uprising, the nationalist elements in Damascus were eager to participate when one arose.[9]

Mistreatment of the Druze population

The spark that ignited the Great Syrian Revolt was French treatment of the Druze population.[10] In 1923, the leaders of Jabal al-Druze, a region in the southeast of the Mandate of Syria, had come to an agreement with French authorities, hoping for the same degree of autonomy they had enjoyed under the Ottoman Empire.

Druze society was governed by a council of notables, the majlis, who selected one of their number to a limited executive position. Traditionally, this role had been dominated by the al-Atrash family since the defeat of the Lebanese Druze in 1860.[10] But in 1923, shortly after the agreement made with the French, Selim al-Atrash resigned. Seizing upon the disunity of the al-Atrash family in selecting a successor, the majlis struck at their power by choosing a French officer of the Service des Renseignements, Captain Carbillet. Though he was initially only appointed for three months, later his term was extended indefinitely.

Captain Carbillet embarked upon a series of successful modernization reforms, but in the process, he collected Druze taxes in full, disarmed the population, and used the forced labor of prisoners and peasants, upsetting a significant part of the population.[10] In the meantime, Sultan al-Atrash, the most ambitious member of the al-Atrash family, sent a delegation to Beirut to inform the French High Commissioner, General Maurice Sarrail, that Captain Carbillet’s actions were antagonizing most of the Druze population. Instead of hearing the delegates, Sarrail imprisoned them. Upon hearing of this, the Druze returned their support to the al-Atrash family, which by this point was backing Sultan al-Atrash, and rebelled against the French (and indirectly against the majlis, who had elevated them to power).

Revolution

On August 23, 1925 Sultan Pasha al-Atrash officially declared revolution against France. Calling upon Syria's various ethnic and religious communities to oppose the foreign domination of their land, al-Atrash managed to enlist the aid of large sections of the population in a revolt that now spread throughout Syria, led by such notable figures as Hassan al-Kharrat, Nasib al-Bakri, Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar and Fawzi al-Qawuqji.

Fighting began with the Battle of al-Kafr on July 22, 1925, the Battle of al-Mazra'a on August 2–3, 1925, and the subsequent battles of Salkhad, al-Musayfirah and Suwayda. After initial rebel victories against the French, France sent thousands of troops to Syria and Lebanon from Morocco and Senegal, equipped with modern weapons, compared to the meager supplies of the rebels. This dramatically altered the results and allowed the French to regain many cities, although fierce resistance lasted until the spring of 1927. The French sentenced Sultan al-Atrash and other national leaders to death, but al-Atrash escaped with the rebels to Transjordan and was eventually pardoned. In 1937, after the signing of the Franco-Syrian Treaty, he returned to Syria where he was met with a huge public reception.

The course of the war

Initially, the French were ill-equipped to respond to the outbreak of violence. In 1925, the number of French troops in the Mandate of Syria was at its lowest ever, numbering only 14,397 men and officers, with an additional 5,902 Syrian auxiliaries, down from 70,000 in 1920.[10] In 1924, the French representative reporting to the Permanent Mandates Commission in 1924 wrote that “the little state of Djebel-Druze [is] of small importance and [has] only about 50,000 inhabitants.”[11] Consequently, the Druze, when they revolted in September 1925 met with great success, and after a series of victories, including the annihilation of a French relief column, captured the fort at al-Suwayda.[10]

Instead of engaging the Druze in the winter, the French decided to temporarily withdraw, a decision noted by the new high commissioner, Henry de Jouvenel, to be a tactical error, as it underrepresented French military strength and encouraged a regional rebellion to achieve national dimensions.[10] Indeed, the weak immediate response of the French invited the intervention of disaffected local elite, tribesmen, and loosely connected nationalists based in Damascus.

First to seize upon the opportunity presented by the revolt were the nomadic tribes, who used the absence of French authority – troops had been drawn away to concentrate on the rebelling region – to prey upon farmers and merchants, thereby creating an atmosphere of sympathy for the rebellious Druze.[10]

The nationalists seized upon the Druze revolt in relatively short order, forging an alliance with Sultan al-Atrash within six weeks of the uprising’s commencement, and establishing a National Provisional Government in Jabal-Druze with al-Atrash as President and Dr. Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar, leader of the People’s Party, as Vice President.[9]

In response to the outbreak of violence, Jouvenal declared free and popular elections for every area that had not been affected by the rebellion in the beginning of 1926.[12] Most elections were held peacefully. However, in two cities, Homs and Hama, the local elites refused to allow elections to be held. A two-day uprising led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji and largely supported by the local population occurred in Hama on 4–5 October 1925. This was followed in September 1926 by a full-fledged insurrection. French forces rushed to put down the new threat, which gave the rebellion added life elsewhere. At the time, the lack of troops meant that for the French to focus on Homs and Hama, they had to neglect other regions, allowing the revolt to spread.[13] Within two months the Homs-Hama region fell, but the conflict there bought rebels elsewhere much-needed breathing room, and taught the rebels in Damascus a valuable lesson about troop placement.[13]

Despite the revolts in Homs and Hama, the turn-out for the elections suggested to the French that the Syrian people had a desire for peace; in the rural areas around Homs and Hama, where no violence was reported, voter turn-out was 95%.[12] Further, it revealed that many of the belligerents were local elites, and when full amnesty was again offered in February 1926, the entire country, with the exception of Jebal-Druze and Damascus, was pacified.[12]

The lessons the rebels learned from Homs and Hama were many, and that sustained the rebellion for a further year and a half.[14] Homs and Hama were lost because the rebels concentrated their forces in the face of overwhelming French firepower, because they fortified their position and waited for the French to arrive, and because they made no attempt to sever French lines of communication.[15] In Damascus, the rebels were dispersed, so that no random artillery fire would defeat them. Further, when the Druze attacked Damascus, they did so from several directions. Both groups repeatedly cut French lines of communication, and while the French suffered few difficulties in restoring them, the psychological effect the destruction had on them was significant.[15]

Despite the breadth of the rebellion and the initial rebel successes, the persistence of the French made its defeat inevitable. By early 1926, they had increased their troop numbers to 50,000, roughly the size of the total Druze population.[16] By spring, much of Damascus had been destroyed by artillery fire, and the nationalist leadership had been forced into exile.[17] In the spring of the following year, the Druze were decisively defeated, and Sultan al-Atrash went into exile in Transjordan to escape the death penalty.

Results

The Great Syrian Revolt, while a loss for the rebels, did result in changes in the French attitude toward imperialism. Direct rule was believed to be too costly, and in Syria, the threat of military intervention was replaced with diplomatic negotiation. A softer approach to Syrian rule was taken, and in March 1928, just a year after the rebellion was put down, a general amnesty was announced for Syrian rebels. A small addendum was attached, decreeing that the rebellion’s leadership, including Sultan al-Atrash and Dr. Shahbandar, would not be allowed to return.

The impact on Syria itself was profoundly negative. At least 6,000 rebels were killed, and over 100,000 people were left homeless, a fifth of whom made their way to Damascus. After two years of war, the city was ill-equipped to deal with the influx of displaced Syrians, and Hama was similarly devastated. Across Syria, towns and farms had suffered significant damage, and agriculture and commerce temporarily ceased.[17]

See also

Further reading

- Michael Provence, "The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism", University of Texas Press, 2005.

- Anne-Marie Bianquis et Elizabeth Picard, Damas, miroir brisé d'un orient arabe, édition Autrement, Paris 1993.

- Lenka Bokova, La confrontation franco-syrienne à l'époque du mandat – 1925–1927, éditions l'Harmattan, Paris, 1990

- Général Andréa, La Révolte druze et l'insurrection de Damas, 1925–1926, éditions Payot, 1937

- Le Livre d'or des troupes du Levant : 1918–1936. <Avant-propos du général Huntziger.>, Préfacier Huntziger, Charles Léon Clément, Gal. (S. l.), Imprimerie du Bureau typographique des troupes du Levant, 1937.

References

- 1 2 3 Miller, 1977, p. 547.

- 1 2 3 Khoury, 1981, pp. 442-444.

- ↑ Moosa, p. 282.

- ↑ Betts, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Betts, p. 86.

- ↑ Gouraud, Henri. La France En Syrie. [Corbeil]: [Imp. Crété], 1922: 15

- ↑ Khoury, Philip S. "The Tribal Shaykh, French Tribal Policy, and the Nationalist Movement in Syria between Two World Wars." Middle Eastern Studies 18.2 (1982): 184

- ↑ Khoury, Philip S. "The Tribal Shaykh, French Tribal Policy, and the Nationalist Movement in Syria between Two World Wars." Middle Eastern Studies 18.2 (1982): 185

- 1 2 Khoury, 1981, pp. 453-455.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Miller, Joyce Laverty (1977). "The Syrian Revolt of 1925". International Journal of Middle East Studies. pp. 550–555.

- ↑ League of Nations, Permanent Mandates Commission, Minutes of the Fourth Session (Geneva, 1924), p. 31

- 1 2 3 Miller, 1977, pp. 560-562.

- 1 2 Bou-Nacklie, N.E. "Tumult in Syria's Hama in 1925: The Failure of a Revolt." Journal of Contemporary History 33.2 (1998): 274

- ↑ Bou-Nacklie, N.E. "Tumult in Syria's Hama in 1925: The Failure of a Revolt." Journal of Contemporary History 33.2 (1998): 288-289

- 1 2 Bou-Nacklie, N.E. "Tumult in Syria's Hama in 1925: The Failure of a Revolt." Journal of Contemporary History 33.2 (1998): 289

- ↑ Khoury, Philip S. "Factionalism Among Syrian Nationalists During the French Mandate." International Journal of Middle East Studies 13.04 (1981): 461

- 1 2 Khoury, Philip S. (1981). Factionalism Among Syrian Nationalists During the French Mandate. pp. 460–461.

Bibliography

- Betts, Robert Brenton (2010). The Druze. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300048106.

- Miller, Joyce Laverty (October 1977). "The Syrian Revolt of 1925". International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 8 (4): 545–563. doi:10.1017/S0020743800026118.

- Khoury, Philip S. (November 1981). "Factionalism Among Syrian Nationalists During the French Mandate". International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 13 (4): 441–469. doi:10.1017/S0020743800055859.

- Khoury, Philip S. (1982). "The tribal shaykh, French tribal policy, and the nationalist movement in Syria between two world wars". Middle Eastern Studies. 18 (2): 180–193. doi:10.1080/00263208208700504.

- Bou-Nacklie, N.E. (January 1998). "Tumult in Syria's Hama in 1925: The Failure of a Revolt". Journal of Contemporary History. 33 (2): 273–289. doi:10.1177/002200949803300206.