HMS Centurion (1732)

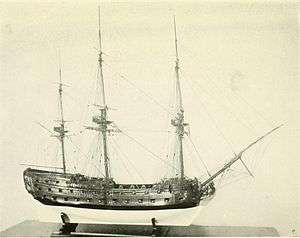

Model of the Centurion, made in 1748 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Centurion |

| Ordered: | 17 October 1729 |

| Builder: | Portsmouth Dockyard |

| Laid down: | 9 September 1729 |

| Launched: | 6 January 1732 |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1769 |

| Notes: |

|

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line |

| Tons burthen: | 1005 bm |

| Length: | 144 ft (43.9 m) (gundeck) |

| Beam: | 40 ft (12.2 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 16 ft 5 in (5.0 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Sail plan: | Full rigged ship |

| Armament: |

|

HMS Centurion was a 60-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Portsmouth Dockyard and launched on 6 January 1732.[1] At the time of Centurion's construction, the 1719 Establishment dictated the dimensions of almost every ship being built. Owing to concerns over the relative sizes of British ships compared to their continental rivals, Centurion was ordered to be built 1 ft (0.3 m) wider across the beam than the Establishment prescribed. HMS Rippon was similarly built to non-Establishment dimensions at the same time.[2]

Early career

Centurion was commissioned in 1734 under the command of Captain Francis Dansays.[3] She served in the Channel Fleet, and took part in Sir John Norris's expedition to Lisbon in 1736, under the command of Captain George Proctor. On the outward voyage she carried John Harrison, who was trialling his first marine timekeeper 'H1'.[4] Proctor died at Lisbon on 4 October 1736, and was succeeded as commander by Captain John Durell.[3]

Captain George Anson took command in December 1737, and led a small squadron to the African coast, then to Jamaica, before arriving back in England in late 1739.[3] She then underwent a refit at Portsmouth, at a cost of £4,791.4.8d, between August 1739 and January 1740 to prepare for a special mission to harass Spanish shipping along the coast of South America and interdict the Manila galleons.[3]

Anson's circumnavigation

With the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession, Anson was placed in charge of a squadron of six ships, consisting of the Centurion, Gloucester 50, Severn 50, Pearl 40, Wager 28, and the sloop Trial 8, plus two store ships Anna and Industry, and instructed to sail to Manila and capture the Spanish colony.[5] Another squadron was to be despatched under Captain Cornwall, which would sail to Manila via Cape Horn. The two squadrons would intercept Spanish shipping as they sailed, and on their rendezvousing at Manila, would refit, replenish and await further orders.[6]

Despite problems manning the ships, Anson sailed on 18 September 1740, with the Centurion as his flagship.[3][5] The squadron called at Madeira, Brazil, Port St Julian and Argentina, eventually reaching Cape Horn by March 1741. By now the Spanish had been alerted to the planned attempt on Manila and had despatched a squadron of their own.[5] A series of gales dispersed the ships of the fleet, and the crews were greatly reduced by disease.[5] Anson pressed on, capturing several Spanish merchants, including the Nuestra Señora del Monte Carmelo and the Nuestra Señora del Arranzazú. The squadron continued to raid Spanish settlements, and intercept Spanish merchants, before Anson sailed the Centurion and the Gloucester to China.[5] The Gloucester was in a state of such disrepair that Anson ordered her scuttled, transferring her crew to the Centurion, and finally landing at Tinian on 15 August.[5] Anson and a number of his crew landed, but on 21 September a typhoon blew the Centurion out to sea. Fearing her lost, Anson made preparations to sail to China in a modified Spanish bark, but the Centurion had survived the gale, and her crew were able to sail her back to rejoin Anson.[5]

The Centurion reached Macau with 200 scurvy-ridden crew on 12 November 1742, and underwent a refit. Anson decided to cruise off the Philippines in the hope of intercepting Spanish treasure galleons, and on 20 June the galleon Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, carrying 36 guns, was sighted.[5] The Centurion overhauled her and brought her to battle. After a brief engagement that left 67 Spanish dead and a further 84 wounded, to just two of the Centurion’s crew killed and another 17 wounded, the Covodonga was taken.[3][5] Anson commissioned her into his fleet the following day, placing her under the command of Captain Philip Saumarez.[3] The two ships sailed into Canton on 11 July, where Anson sold the Covodonga, and after re-provisioning, sailed for England aboard the Centurion on 15 December 1743.[5]

The Centurion arrived back at Spithead on 15 June 1744, the only ship of the original squadron to have survived the entire voyage.[3] She was declared totally worn out, and on 10 April 1744 the Admiralty ordered the construction of a replacement ship.[3] This was never carried out, and instead a new order on 1 December 1744 instructed that Centurion was to undergo a Middling Repair at Portsmouth. This took place between September 1744 and September 1746, and saw her reduced to 50 guns.[1][3] She was briefly renamed Eagle on 15 December 1744, but this was reverted to Centurion on 15 November 1745.[3]

Later career

Centurion was recommissioned in September 1746, and placed under the command of Captain Peter Denis.[3] She was present at the Battle of Cape Finisterre on 3 May 1747, as part of fleet under her old commander, now Rear-Admiral George Anson.[3] She played a significant role, as described in a topical song of the time:

- The Centurion first led the van, (bis)

- And held 'em till we came up;

- Then we their hides did sorely bang,

- Our broadsides we on them did pour, (bis)

- We gave the French a sower drench,

- And soon their topsails made them lower.

- And when they saw our fleet come up, (bis)

- They for quarters call'd without delay,

- And their colours they that moment struck

- O! how we did rejoice and sing, (bis)

- To see such prizes we had took,

- For ourselves and for George our King.[7]

She became part of Sir Peter Warren's fleet in 1748, and came under the command of Captain Augustus Keppel in August that year.[3] She underwent further work in September 1748, having her quarterdeck lengthened, after which she sailed to the Mediterranean.[3]

Centurion was paid off in 1752, and underwent another Middling Repair, this time at Chatham, between October 1752 and August 1753. She was recommissioned in October 1754 under the command of Captain William Mantell, this time serving as the flagship of her old commander, Commodore Augustus Keppel.[3] She sailed to Virginia in 1754, and then to Nova Scotia in 1756, before returning to Britain. She sailed again for North America in April 1757, and was present at the Siege of Louisbourg in 1758, followed by the assault on Quebec in 1759.[3] She underwent another survey in 1760, before passing that year under the command of Captain James Galbraith. She sailed to Jamaica in 1760, where she spent time as the flagship of Sir James Douglas.[3] She was active in the operations against Havana in the summer of 1762, after which she was again paid off.[3]

A further repair at Woolwich followed, after which Centurion was commissioned in May 1763 under the command of Captain Augustus Hervey.[3] She was present in the Mediterranean until 1766, spending the period between 1764 and 1766 as the flagship of Commodore Thomas Harrison.[3] She was paid off for the final time in September 1766. She was surveyed in May 1769, after which she was broken up by Admiralty Order at Chatham, with the work being completed by 18 December 1769.[3]

Legacy

The figurehead of the Centurion, a 16-foot-tall (4.9 m) lion, was presented to the Duke of Richmond by George III when the ship was broken up. It was used for a while as an inn sign at Goodwood, but William IV asked for it from the Duke, and used it as a staircase ornament at Windsor Castle. The King later on presented it to Greenwich Hospital, with directions to place it in one of the wards, which he desired should be called the Anson Ward. It remained there until 1871 when it was removed to the playground of the Naval School, where owing to the action of the weather it unfortunately crumbled to pieces.[7] All that remained was a four-foot high lion’s paw which was eventually recognised as a piece of significant historical interest and returned to Shugborough Hall during the 1920s. Today it adorns a wall in the mansion house's Verandah Passage.[8]

At one time the following lines were inscribed beneath it:

- Stay, traveller, a while, and view

- One who has travelled more than you;

- Quite round the globe, thro' each degree,

- Anson and I have ploughed the sea.

- Torrid and frigid zones have pass'd

- And-safe ashore arrived at last-

- In ease with dignity appear,

- He in the House of Lords-I here.[7]

In addition to eyewitness accounts of Anson's circumnavigation, Patrick O'Brian's novel The Golden Ocean is an accurate, though fictional, account of the voyage.[5]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Lavery, Ships of the Line vol.1, p. 170.

- ↑ Lavery, Ships of the Line vol.1, p81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 112.

- ↑ Bernstein. The Birth of Plenty. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Paine. Ships of Discovery and Exploration. pp. 30–1.

- ↑ Walter. A Voyage Round the World. p. 12.

- 1 2 3 HMS Centurion, Battleships-Cruisers.co.uk.

- ↑ Information from Staffordshire County Council

References

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- Winfield, Rif, British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates, pub Seaforth, 2007, ISBN 1-86176-295-X

- Lavery, Brian (2003) The Ship of the Line - Volume 1: The development of the battlefleet 1650-1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- Walter, Richard. A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1740-4. Aylesbury: Heron Books.

- Bernstein, William J (2004). The Birth of Plenty: How the Modern Economic World was Launched. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-142192-0.

- HMS Centurion. Battleships-Cruisers.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- Paine, Lincoln P. (2001). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-98415-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Centurion (1732). |

- Centurion, 60 guns. Photos of a model of Centurion at the National Maritime Museum.