HMS Salvia (K97)

HMS Salvia (K97) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Salvia |

| Namesake: | Salvia genus of plants |

| Owner: | Royal Navy |

| Ordered: | 31 August 1939[1] |

| Builder: | William Simons & Co Ltd,[1] Renfrew |

| Yard number: | 731[2] |

| Laid down: | 26 September 1939[1] |

| Launched: | 6 August 1940[1][2] |

| Commissioned: | 20 September 1940[1] |

| Out of service: | 24 December 1941[1] |

| Identification: | Pennant number K97[1][2] |

| Fate: | torpedoed & sunk by U-568[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Flower-class corvette |

| Type: | Corvette |

| Tonnage: |

|

| Displacement: | 925 tons |

| Length: | 205 ft (62.5 m) o/a[2] |

| Beam: | 33 ft (10.1 m)[2] |

| Draught: | 14 ft 10 in (4.52 m)[2] |

| Installed power: | 2,750 ihp (2,050 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 16 knots (30 km/h) |

| Range: |

|

| Crew: | |

| Armament: |

|

| Notes: | fitted with towing gear |

HMS Salvia (K97) was a Flower-class corvette of the Royal Navy. She was ordered on the eve of the Second World War and entered service in September 1940. She is notable for having rescued many survivors from the sinking of the prison ship SS Shuntien on 23 December 1941. A few hours later, on Christmas Eve 1941, Salvia too was torpedoed. The corvette sank with all hands, and all of the survivors that she had rescued from Shuntien were also lost.

Building

The Admiralty introduced corvettes as part of the British re-armament before the Second World War. They were simpler and cheaper to build than frigates and were designed to be built by yards that did not normally build naval ships. The Flower class was intended for duties such as convoy escort and minesweeping.

The Admiralty ordered Flower-class corvettes in batches, spreading each batch between a number of shipbuilders that normally built merchant ships. The first batch was of 26 corvettes, ordered on 25 July 1939. The second batch was of 30 ships, ordered on 31 August 1939, the day before Britain entered the Second World War. Salvia was one of this second batch.

Salvia was one of several Flowers ordered from William Simons and Company,[1] a shipbuilder in Renfrew,[4] Scotland. Salvia's keel was laid on 26 September 1939, she was launched on 6 August 1940 and she was commissioned into the Royal Navy on 20 September.[1]

She was commanded by Lt Cdr John Isdale Miller, DSO, RD, RNR, who had lately commanded the anti-submarine trawler HMS Blackfly.[5] Miller and his new crew took Salvia to Tobermory in the Isle of Mull for training exercises.[6]

Characteristics

Being in one of the earlier batches to be ordered, Salvia was one of the "unmodified" members of the Flower class. All unmodified Flowers had a raised fo'c's'le, a well deck, then the bridge, and a continuous deck running aft. The design was highly seaworthy but in a heavy sea she would have shipped a lot of water. Every dip of the fo'c's'le into an oncoming wave was followed by a cascade of water into her well deck amidships.[7] Her crew was quartered in her fo'c's'le but her galley was aft, which was a poor messing arrangement.[8]

Operation Collar

On 16 November 1940 Salvia and her sister ships HMS Gloxinia, HMS Hyacinth and HMS Peony sailed from the Port of Liverpool escorting a convoy as part of Operation Collar.[6] On 25/26 November the convoy passed Gibraltar and the four Flowers became part of Force F, which was led by the cruisers HMS Manchester and HMS Southampton, reinforced by the destroyer HMS Hotspur.[6] The Flowers formed the 10th Corvette Group and were the first corvettes to join the British Mediterranean Fleet.[6]

From Gibraltar the convoy and Force F sailed east with Force H, and on 27 September an Italian Regia Marina force attacked.[6] In the ensuing Battle of Cape Spartivento the corvettes protected the merchant ships Clan Forbes, Clan Fraser and New Zealand Star while Force H and other ships of Force F, later joined by Force D which had sailed from Alexandria, held off the Italian attack.[6] The convoy then continued to Malta, where the corvettes refuelled.[6] The two Clan Line freighters stayed in Malta to unload but Manchester, Southampton, the destroyers HMS Defender and HMS Hereward and the four corvettes then escorted the Blue Star Line refrigerated ship New Zealand Star to Alexandria.[6]

Battle of Greece

On 7 January 1941 the 10th Corvette Group sailed from Alexandria escorting RFA Brambleleaf bound for Souda Bay in Crete.[6] However, en route the corvettes were diverted to Malta to support Operation Excess, and on 9 January they met Force A which included the battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Warspite, aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious and seven destroyers.[6] Force A and the corvettes reached Alexandria on 18 January.[6]

In February 1941 Hyacinth and Salvia escorted convoys in the eastern Mediterranean.[6] In April 1941 Salvia was minesweeping in Greece and detonated five magnetic mines near the Port of Piraeus.[6]

On 24 April Hyacinth and Salvia sailed from Souda Bay to Porto Rafti in Attica and Nafplio in the Peloponnese to help the Evacuation of Commonwealth forces in the Battle of Greece.[6] Salvia then took part in the escort of Convoy AG 13, which took evacuated troops to Crete. On 28/29 April Hyacinth and Salvia evacuated troops from Kapsali Bay on the island of Kythera to Souda Bay.[6]

On 14 May Salvia was still at Souda Bay.[6] It is not clear what role she may have played once the German invasion of Crete began on 20 May.[6]

On 3 June 1941 Lt Cdr Miller was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[5]

Loss of SS Shuntien

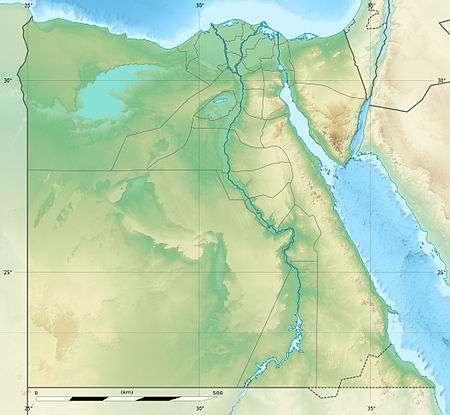

In the Western Desert Campaign in December 1941 Salvia, still commanded by Lt Cdr Miller,[1] was part of the escort of convoy Convoy TA 5 from Tobruk in eastern Libya to Alexandria in Egypt.

At about 1902 hrs on the evening of 23 December off the coast of Cyrenaica, eastern Libya, the German submarine U-559 torpedoed and sank SS Shuntien: a prison ship in the convoy that was carrying between 800 and 1,000[9] Italian and German prisoners of war, guarded by more than 40 soldiers of the Durham Light Infantry (DLI).[10] Shuntien sank within five minutes without having been able to launch any of her lifeboats.[11]

Salvia rescued Shuntien's Master, William Shinn, 46 of the ship's officers and men and an unknown number of her prisoners, DEMS gunners and DLI guards.[3] The total number of survivors that she rescued was about 100.[9][12] The Hunt-class destroyer HMS Heythrop rescued a smaller number: between 11[12] and 19.[11]

Loss of HMS Salvia

Salvia then made for Alexandria. A few hours later, at about 0135 hrs on 24 December, she was off the Egyptian coast about 100 nautical miles (190 km) west of Alexandria when the Type VIIC German submarine U-568 fired four torpedoes at her.[3] One of the torpedoes hit Salvia, breaking her in two and spilling her heavy black bunker oil onto the surface of the sea.[3] The fuel caught fire and her stern section rapidly sank, followed by her bow section a few minutes later.[3]

A sister ship, HMS Peony, came to look for survivors.[3] She sighted a patch of oil on the surface of the sea but found no-one left alive.[3]

On 8 January 1942 Lt Cdr Miller was posthumously awarded a bar to his DSC.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2013). "HMS Salvia (K97)". uboat.net: Allied Warships. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cameron, Stuart; Allan, Bruce; Biddulph, Bruce; Campbell, Colin; Ward-McQuaid, John (2002–2013). "HMS Salvia". Clydebuilt database. Clydesite.co.uk. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2013). "HMS Salvia (K97)". uboat.net: Ships hit by U-boats. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "William Simons and Co". Grace's Guide: The Best of British Engineering 1750–1960s. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2013). "John Isdale Miller DSO, DSC, RD, RNR". uboat.net: Allied Warship Commanders. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Walters, Mark (3 September 2008). "HMS Salvia". The Flower Class Corvette and WWII Royal Navy Forums. Yuku. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Milner, Marc (1985). North Atlantic Run. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-87021-450-0.

- ↑ Brown, David K (2000). Nelson to Vanguard: Warship Design and Development, 1923–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. not cited. ISBN 155750492X.

- 1 2 "23 December 1941: 700 Prisoners Killed". Malta: War Diary. WordPress. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "For those in Peril on the sea". Durham Light Infantry 1920–1946. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Shuntien II". WikiSwire. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013. N.b. WikiSwire is a wiki with multiple authors. Unlike Wikipedia it does not generally cite previously published sources to verify its content.

- 1 2 Churchill, Michael (31 May 2005). "My Uncle Bill". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

Coordinates: 31°28′N 28°00′E / 31.46°N 28.00°E