Hartley function

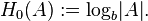

The Hartley function is a measure of uncertainty, introduced by Ralph Hartley in 1928. If we pick a sample from a finite set A uniformly at random, the information revealed after we know the outcome is given by the Hartley function

If the base of the logarithm is 2, then the unit of uncertainty is the shannon. If it is the natural logarithm, then the unit is the nat. Hartley used a base-ten logarithm, and with this base, the unit of information is called the hartley in his honor. It is also known as the Hartley entropy.

Hartley function, Shannon's entropy, and Rényi entropy

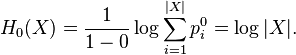

The Hartley function coincides with the Shannon entropy (as well as with the Rényi entropies of all orders) in the case of a uniform probability distribution. It is actually a special case of the Rényi entropy since:

But it can also be viewed as a primitive construction, since, as emphasized by Kolmogorov and Rényi, the Hartley function can be defined without introducing any notions of probability (see Uncertainty and information by George J. Klir, p. 423).

Characterization of the Hartley function

The Hartley function only depends on the number of elements in a set, and hence can be viewed as a function on natural numbers. Rényi showed that the Hartley function in base 2 is the only function mapping natural numbers to real numbers that satisfies

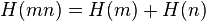

-

(additivity)

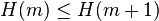

(additivity) -

(monotonicity)

(monotonicity) -

(normalization)

(normalization)

Condition 1 says that the uncertainty of the Cartesian product of two finite sets A and B is the sum of uncertainties of A and B. Condition 2 says that larger set has larger uncertainty.

Derivation of the Hartley function

We want to show that the Hartley function, log2(n), is the only function mapping natural numbers to real numbers that satisfies

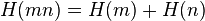

-

(additivity)

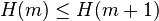

(additivity) -

(monotonicity)

(monotonicity) -

(normalization)

(normalization)

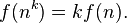

Let ƒ be a function on positive integers that satisfies the above three properties. From the additive property, we can show that for any integer n and k,

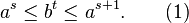

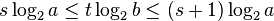

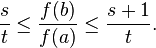

Let a, b, and t be any positive integers. There is a unique integer s determined by

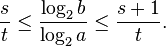

Therefore,

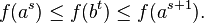

and

On the other hand, by monotonicity,

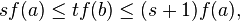

Using Equation (1), we get

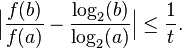

and

Hence,

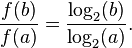

Since t can be arbitrarily large, the difference on the left hand side of the above inequality must be zero,

So,

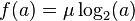

for some constant μ, which must be equal to 1 by the normalization property.

See also

References

- This article incorporates material from Hartley function on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

- This article incorporates material from Derivation of Hartley function on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.