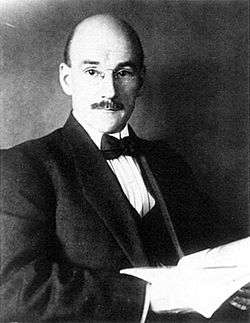

Henry H. Goddard

Henry Herbert Goddard (August 14, 1866 – June 18, 1957) was a prominent American psychologist and eugenicist in the early 20th century. He is known especially for his 1912 work The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness, which he himself came to regard as deeply flawed, and for being the first to translate the Binet intelligence test into English in 1908 and distributing an estimated 22,000 copies of the translated test across the United States. He also introduced the term "moron" into the field.

He was the leading advocate for the use of intelligence testing in societal institutions including hospitals, schools, the legal system and the military. He played a major role in the emerging field of clinical psychology, in 1911 helped to write the first U.S. law requiring that blind, deaf and mentally retarded children be provided special education within public school systems, and in 1914 became the first American psychologist to testify in court that subnormal intelligence should limit the criminal responsibility of defendants.

Early life

Goddard was born in East Vassalboro, Maine, the fifth and youngest child and only son of farmer Henry Clay Goddard and his wife Sarah Winslow Goddard, who were devout Quakers. (Two of his sisters died in infancy.) His father was gored by a bull when the younger Goddard was a small child, and eventually lost his farm and had to work as a farmhand; he died of his lingering injuries when the boy was nine. The younger Goddard went to live with his married sister for a brief time, but in 1877 was enrolled at the Oak Grove Seminary , a boarding school in Vassalboro.

During this period, Sarah Goddard began a new career as a traveling Quaker preacher; she married missionary Jehu Newlin in 1884, and the couple regularly traveled throughout the United States and Europe. In 1878, Henry Goddard became a student at the Friends School in Providence, Rhode Island. During his youth he began an enduring friendship with Rufus Jones, who would go on to co-found (in 1917) the American Friends Service Committee, which received the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize.

Goddard entered Haverford College in 1883, where he played on the football team, and graduated in 1887; he took a year off from his studies to teach in Winthrop, Maine, from 1885 to 1886. After graduating, he traveled to California to visit one of his sisters, and stopped en route in Los Angeles to present some letters of introduction at the University of Southern California, which had been established just seven years earlier. After seeking posts in the Oakland area for several weeks, he was surprised to receive an offer of a temporary position at USC, teaching Latin, history and botany. He also served as co-coach (with Frank Suffel) of the first USC football team in 1888, with the team winning both of its games against a local athletic club.[1] But he departed immediately thereafter, returning to Haverford to earn his master's degree in mathematics in 1889.

From 1889 to 1891, he became principal of the Damascus Academy, a Quaker school in Damascus, Ohio, where he also taught several subjects and conducted chapel services and prayer meetings. On August 7, 1889, he married Emma Florence Robbins, who became one of the two other teachers at the Academy. In 1891 he returned to teach at the Oak Grove Seminary in Vassalboro, becoming principal in 1893. In 1896 he enrolled at Clark University, intending to study only briefly, but he remained three years and received his doctorate in psychology in 1899. He then taught at the State Normal School in West Chester, Pennsylvania until 1906.

Vineland

From 1906 to 1918, Goddard was the Director of Research at the Vineland Training School for Feeble-Minded Girls and Boys in Vineland, New Jersey, which was the first known laboratory established to study mental retardation. While there, he is quoted as stating that "Democracy, then, means that the people rule by selecting the wisest, most intelligent and most human to tell them what to do to be happy." [Italics are Goddard's.][2]

At the May 18, 1910 annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of the Feeble-Minded, Goddard proposed definitions for a system for classifying individuals with mental retardation based on intelligence quotient (IQ). Goddard used the terms moron for those with an IQ of 51-70, imbecile for those with an IQ of 26-50, and idiot for those with an IQ of 0-25 for categories of increasing impairment. This nomenclature was the standard of the field for decades. A moron, by his definition, was any person with mental age between eight and twelve. Morons, according to Goddard, were unfit for society and should be removed from society either through institutionalization, sterilization, or both. What Goddard failed to see was that his bias against morons would greatly influence his data later.

Goddard's best-known work, The Kallikak Family, was published in 1912. He had studied the background of several local groups of people which were somewhat distantly related, and concluded that they were all descended from a single Revolutionary War soldier. Martin Kallikak first married a Quaker woman. All of the children that came from this relationship were "wholesome" and had no signs of retardation. Later, it was discovered that Kallikak had an affair with a "nameless feeble-minded woman".[3] The result of this union led to generations of criminals. Goddard called this generation "a race of defective degenerates". While the book rapidly became a success and was considered to be made into a Broadway play, his research methods were soon called into question; within ten years he came to agree with the critics, and no longer promoted the conclusions he had reached.

Goddard was a strong advocate of eugenics. Although he believed that "feeble-minded" people bearing children was inadvisable, he hesitated to promote compulsory sterilization – even though he was convinced that it would solve the problem of mental retardation – because he did not think such a plan could gain widespread acceptance. Instead he suggested that colonies should be set up where the feeble-minded could be segregated.

Goddard established an intelligence testing program on Ellis Island in 1913. The purpose of the program was to identify "feeble-minded" persons whose nature was not obvious to the subjective judgement of immigration officers, who had previously made these judgements without the aid of tests.[4] When he published the results in 1917, Goddard stated that his results only applied to immigrants traveling steerage and did not apply to people traveling in first or second class.[5] He also noted that the population he studied had been preselected, cutting out those who were either "obviously normal" or "obviously feeble-minded", and stated that he made "no attempt to determine the percentage of feeble-minded among immigrants in general or even of the special groups named – the Jews, Hungarians, Italians, and Russians"; a qualifier omitted in works by opponents of the study of intelligence such as Gould and Kamin.[4]

The program found an estimated 80% of the population of immigrants studied were "feeble-minded". Goddard and his associates tested a group of 35 Jewish, 22 Hungarian, 50 Italian, and 45 Russian immigrants who had been identified as "representative of their respective groups". The results found that 83% of Jews, 80% of Hungarians, 79% of Italians, and 80% of Russians in the study population were feeble-minded. The untrue claim that this referred to findings made by Goddard in respect to the wider population of Jewish, Hungarian, Italian and Russian immigrants has been widely publicized.[4]

Claims are often made that the Immigration Act of 1924 was strongly influenced by intelligence testing. However, the act made no mention of the practice, and it was seldom mentioned in the discussion prior to its enactment.[4]

Goddard also publicized purported race-group differences on Army IQ tests (Army Alpha and Beta) during World War I (the results were, even in their day, challenged as scientifically inaccurate, and later resulted in a retraction from the head of the project, Carl Brigham) and claimed that the results showed that Americans were unfit for democracy.

Later career

In 1918 he became director of the Ohio Bureau of Juvenile Research; in 1922 he became a professor in the Department of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology at the Ohio State University, a position he held until his retirement in 1938. His wife Emma died in October 1936; they had no children. He received an honorary law degree from Ohio State in 1943, and an honorary degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1946. In 1946 he was among the supporters of Albert Einstein's Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists.

By the 1920s, Goddard had come to candidly admit that he had made numerous errors in his early research, and regarded The Kallikak Family as obsolete. It was also noted that Goddard was more concerned about making eugenics popular rather than conducting actual scientific studies. He devoted the later part of his career to seeking improvements in education, reforming environmental influences in childhood, and working toward better child-rearing practices. But others continued to use his early work to support various arguments with which Goddard did not agree, and he was constantly perplexed by the fact that later generations found his studies to be dangerous to society. Henry Garrett of Columbia University was one of the few scientists to continue to use The Kallikak Family as a reference.

Goddard moved to Santa Barbara, California in 1947. He died at his home there at age 90, and his cremated remains were interred with those of his wife at the Siloam Cemetery, 550 N. Valley Avenue, Vineland, New Jersey.

Publications

- The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness (1912)

- Standard method for giving the Binet test (1913)

- Feeble-Mindedness: Its Causes and Consequences (1914)

- School Training of Defective Children (1914)

- The Criminal Imbecile: An Analysis of Three Remarkable Murder Cases (1915)

- Psychology of the Normal and Subnormal (1919)

- Human Efficiency and Levels of Intelligence (1920)

- Juvenile Delinquency (1921)

- Two Souls in One Body? (1927)

- School Training of Gifted Children (1928)

- How to Rear Children in the Atomic Age (1948)

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ In The Trojans: Southern California Football (1974; ISBN 0-8092-8364-6), author Don Pierson suggests that Goddard and Suffel each coached one game. The fact that the games were played two months apart on November 14 and January 19, along with the fact that Goddard was no longer teaching at USC in 1889, lends credibility to the suggestion.

- ↑ Goddard, Psychology of the Normal and Subnormal, page 237

- ↑ Goddard, H. H. (1912). The Kallikak family: A study in the heredity of feeble mindedness. New York: MacMillan.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Snyderman, R.J. Herrnstein (September 1983). "Intelligence tests and the Immigration Act of 1924". American Psychologist. 38 (9): 986–995. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.38.9.986.

- ↑ Goddard, H. H. (1917). "Mental tests and the immigrant". Journal of Delinquency. 2: 243–277.

- Zenderland, Leila (1998). Measuring Minds: Henry Herbert Goddard and the Origins of American Intelligence Testing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44373-3.

- The Vineland Training School. Goddard and Eugenics. http://www.vineland.org/history/trainingschool/history/eugenics.htm

External links

- Works by Henry Herbert Goddard at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry H. Goddard at Internet Archive

- About half of the text of 1913 edition of Goddard's Kallikak Family

- Henry H. Goddard at the College Football Data Warehouse