Henry I, Duke of Guise

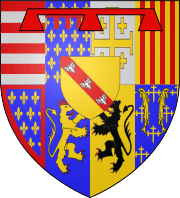

Henry I, Prince of Joinville, Duke of Guise, Count of Eu (31 December 1550 – 23 December 1588), sometimes called Le Balafré (Scarface), was the eldest son of Francis, Duke of Guise, and Anna d'Este. His maternal grandparents were Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, and Renée of France. Through his maternal grandfather, he was a descendant of Lucrezia Borgia and Pope Alexander VI.

In 1576 he founded the Catholic League to prevent the heir, King Henry of Navarre, head of the Huguenot movement, from succeeding to the French throne. A key figure in the French Wars of Religion, he was one of the namesakes of the War of the Three Henrys. A powerful opponent of the Queen Mother, Catherine de' Medici, he was assassinated by the bodyguards of her son, King Henry III.

Catholic League

He succeeded his father in 1563 as Duke of Guise and Grand Maître de France. He fought the Turks in Hungary in 1565,[1] and on his return, he became one of the leaders of the Catholic faction in the French Wars of Religion. He fought at the Battle of Saint-Denis in 1567, Battle of Jarnac, successfully defended Poitiers during a siege[2] and fought at the Battle of Moncontour. His love affair with Margaret of Valois in 1570 offended her brother, Charles IX of France and the Queen Mother, Catherine de' Medici, but his marriage to Catherine of Cleves restored his fortunes. Considering the Huguenot leader Admiral Coligny the architect of his father's assassination during the siege of Orléans in 1563, he is a suspect in the murder of the Admiral in August 1572. This was quickly followed by the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre which took place on the occasion of Margaret's marriage to the Huguenot, Henry of Navarre.

Henry was wounded at the Battle of Dormans on 10 October 1575, and was thereafter known, like his father, as "Le Balafré". With a charismatic and brilliant public reputation, he rose to heroic stature among the Catholic population of France as an opponent of the Huguenots.

In 1576 he formed the Catholic League to keep the new heir, Henry of Navarre, off the throne. The talent and dash of Guise contrasted favorably with the vacillation and weakness of Henry III. He was said to have claimed a Carolingian descent and cast eyes on the throne. This led to the stage of the Wars of Religion known as the War of the Three Henries (1584–1588).

However, at the death in 1584 of Francis, Duke of Anjou, the king's brother (which left Henry of Navarre, the Protestant champion, as heir-male), Guise concluded the Treaty of Joinville with Philip II of Spain. This compact declared that the Cardinal de Bourbon should succeed Henry III, in preference to Henry of Navarre. Henry III now sided with the Catholic League (1585), which made war with great success on the Protestants. Guise sent his cousin Charles, Duke of Aumale, to lead a rising in Picardy (which could also support the retreat of the Spanish Armada). Alarmed, Henry III ordered Guise to remain in Champagne; he defied the king and on 9 May 1588 Guise entered Paris, bringing to a head his ambiguous challenge to royal authority in the Day of the Barricades and forcing King Henry to flee.

Assassination

The League now controlled France; the king was forced to accede to its demands and created Guise Lieutenant-General of France. But Henry III refused to be treated as a mere cipher by the League, and decided upon a bold stroke. On 22 December 1588, he spent the night with his current mistress Charlotte de Sauve, the most accomplished and notorious member of Catherine de' Medici's group of female spies known as the "Flying Squadron".[3] The following morning at the Château de Blois, Guise was summoned to attend the king, and was at once assassinated by "the Forty-five", the king's bodyguard, as Henry III looked on.[4] Guise's brother, Louis II, Cardinal of Guise, was likewise assassinated the next day. The deed aroused such outrage among the remaining relatives and allies of Guise that Henry III was forced to take refuge with Henry of Navarre. Henry III was assassinated the following year by Jacques Clément, an agent of the Catholic League.

According to Baltasar Gracian in A Pocket Mirror for Heroes, it was once said of him to Henry III, "Sire, he does good wholeheartedly: those who do not receive his good influence directly receive it by reflection. When deeds fail him, he resorts to words. There is no wedding he does not enliven, no baptism at which he is not godfather, no funeral he does not attend. He is courteous, humane, generous, the honorer of all and the detractor of none. In a word, he is a king by affection, just as Your Majesty is by law."

In literature and the arts

Literature

The Duke of Guise appears as an archetypal Machiavellian schemer in Christopher Marlowe's The Massacre at Paris, which was written about 20 years[5] after the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. The death of the duke is also mentioned, by the ghost of Machiavelli himself, in the opening lines of The Jew of Malta. He appears (as The Guise) in George Chapman's Bussy D'Ambois and its sequel, The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois.

John Dryden and Nathaniel Lee wrote The Duke of Guise (1683),[6] based on events during the reign of Henry III of France.

Equally he appears in the short novel The Princess of Montpensier, by Madame de La Fayette

He is one of the characters in Alexandre Dumas's novel La Reine Margot and its sequels, La Dame de Monsoreau and The Forty-Five Guardsmen.

Stanley Weyman's novel A Gentleman of France includes the Duke of Guise in its tale about the War of the Three Henries.

Stage and film

The Duke is a leading character in the play The Massacre at Paris, by Christopher Marlowe.

George Onslow's 1837 opera Le duc de Guise deals with the duke's assassination.

L'Assassinat du Duc de Guise, Op. 128, first shown at the Salle Charras in Paris on 16 November 1908, was the first film to include a score written by a well-known classical composer, Camille Saint-Saëns.

The duke also has a role in D. W. Griffith's 1916 film Intolerance, part of which covers the lead-up to the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre.

The Duke of Guise plays a significant role in the French movie The Princess of Montpensier. He also appears in both the 1954 version and 1994 version of La Reine Margot.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Henry I, Duke of Guise | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Issue

He married on 4 October 1570 in Paris to Catherine of Cleves (1548–1633), Countess of Eu,[7] by whom he had fourteen children:

- Charles, Duke of Guise (1571–1640), who succeeded him

- Henri (30 June 1572, Paris – 3 August 1574)

- Catherine (3 November 1573) (died at birth)

- Louis III, Cardinal of Guise (1575–1621), Archbishop of Reims

- Charles (1 January 1576, Paris) (died at birth)

- Marie (1 June 1577 – 1582)

- Claude, Duke of Chevreuse (1578–1657) married Marie de Rohan, daughter of Hercule de Rohan, duc de Montbazon

- Catherine (b. 29 May 1579), died young

- Christine (21 January 1580) (died at birth)

- François (14 May 1581 – 29 September 1582)

- Renée (1585 – 13 June 1626, Reims), Abbess of St. Pierre

- Jeanne (31 July 1586 – 8 October 1638, Jouarre), Abbess of Jouarre

- Louise Marguerite, (1588 – 30 April 1631, Château d'Eu), married at the Château de Meudon on 24 July 1605 François, Prince of Conti

- François Alexandre (7 February 1589 – 1 June 1614, Château des Baux), a Knight of the Order of Malta

| French nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Catherine |

Count of Eu 1570–1588 with Catherine |

Succeeded by Charles |

| Preceded by Francis |

Duke of Guise 1563–1588 | |

| Prince of Joinville 1563–1588 | ||

Literature

- Pierre Matthieu, La Guisiade (1589).

- Christopher Marlowe, The Massacre at Paris (1593).

- George Chapman, The Tragedy of Bussy D'Ambois (1607).

- George Chapman, The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois (1613).

- John Dryden & Nathaniel Lee, The Duke of Guise (1683).

See also

References

- ↑ Stuart Carroll, Noble Power During French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 126.

- ↑ Stuart Carroll, Martyrs and Murderers:The Guise Family and the Making of Europe, (Oxford University Press, 2011), 187.

- ↑ Strage, Mark (1976). Women of Power: The Life and Times of Catherine de' Medici. New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 277

- ↑ Strage, pp. 277–278

- ↑ OUP Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe 1998. pp. 294–295

- ↑ Dryden, John. The works, vol 14: Plays, 1993. Los Angeles: University of California, http://www.english.ucla.edu/news/pub/worksdj.asp.

- ↑ Stuart Carroll, Noble Power During French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy, 27.

External links

Media related to Henry I, Duke of Guise at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Henry I, Duke of Guise at Wikimedia Commons