History of Ottawa

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Ottawa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical individuals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The History of Ottawa, capital of Canada, was shaped by events such as the construction of the Rideau Canal, the lumber industry, the choice of Ottawa as the location of Canada's capital, as well as American and European influences and interactions. By 1914, Ottawa's population had surpassed 100,000 and today it is the capital of a G7 country whose metropolitan population exceeds one million.

The origin of the name "Ottawa" is derived from the Algonquin word adawe, meaning "to trade". The word refers to the Indigenous Peoples who used the river to trade, hunt, fish, camp, harvest plants, ceremonies, and for other traditional uses. The first maps made of the area started to name the major river after these peoples.

For centuries, Algonquin people have portaged through the waterways of both the Ottawa River and the Rideau River while passing through the area. French explorer Étienne Brûlé was credited as the first European to see the Chaudière Falls in 1610, and he too had to portage past them to get further inland. No permanent settlement occurred in the area until 1800 when Philemon Wright founded his village near the falls, on the north shore of the Ottawa River.

The construction of the Rideau Canal, spurred by concerns for defense following the War of 1812 and plans made by Lieutenant Colonel John By and Governor General Dalhousie began shortly after September 26, 1826 when Ottawa's predecessor, Bytown was founded. Lt. Colonel John By was an officer of the Royal Engineers commissioned by the British Government in 1826 to superintend the construction of the Rideau Canal.[1]

The founding was marked by a sod turning, and a letter from Dalhousie which authorized Colonel By to divide up the town into lots.[2] The town developed into a site for the timber, and later sawed lumber trade, causing growth so that in 1854, Bytown was created a city and its present more appropriate name, Ottawa was conferred.[1]

Shortly afterward, Queen Victoria chose Ottawa as the capital of Canada; and the parliament buildings on Parliament Hill were soon completed. Also at this time, increased export sales led it to connect by rail to facilitate shipment to markets especially in the United States. In the early 1900s the lumber industry waned as both supply and demand lessened.

Growth continued in the 20th century, and by the 1960s, the Greber Plan transformed the capital's appearance and removed much of the old industrial infrastructure. By the 1980s, Ottawa had become known as Silicon Valley North after large high tech companies formed, bringing economic prosperity and assisting in causing large increases in population in the last several decades of the century. In 2001, the city amalgamated all areas in the former region, and today plans continue in areas such as growth and transportation.

Indigenous peoples and European exploration

With the draining of the Champlain Sea around 10,000 years ago the Ottawa Valley became habitable.[3] The Algonquin people (Anishinaabe) who called the Ottawa River the Kichi Sibi or Kichissippi meaning "Great River" or "Grand River" maintained a trade route along the Ottawa River for a relatively short time.[4][5][6][7][8] The word "Ottawa" is in relation to the Ottawa people, the First Nation who hunted, camped, traded, and traveled in the area, and also lived far to the west along Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. [9]

When Étienne Brûlé in 1610 became the first European to travel up the Ottawa River, followed by Samuel de Champlain in 1613, they were assisted by Algonquin guides.[10][11] Written records show that by 1613 the Algonquins were in control of the Ottawa Valley and the surrounding areas to the west and north.[7]

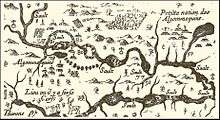

At left is an extract from a map created in 1632 by Samuel de Champlain of the eastern reaches of New France. It shows a portion of the Ottawa River route he took in 1616, with numbers used to indicate sites he visited, significant rapids and aboriginal encampments. Numbers 77 and 91 correspond to the locations of the modern-day City of Ottawa and the Rideau River respectively; # 80 marks the location of the large rapids south of Calumet Island; # 81 shows the site of Allumette Island, inhabited at that time by members of the Algonquin nation; # 82 corresponds roughly to the location of the modern-day village of Fort-Coulonge, and an Algonquin settlement that existed at the time of Champlain's travels.

Champlain wrote about both the Rideau Falls (named by later canoeists) on the eastern part of the early future town, and the Chaudière Falls (named by Champlain) in the west, which would later become employed in the lumber industry. Unlike some parts of Gatineau, and areas much further upstream, there are no indications of any settlement at all in present-day Ottawa for the next two centuries, however the river and the Rideau River had been used for travel.[13][14][15] Chaudière was, and still is impassable by any water traffic, so there were portage paths around it on trips from the mouth of the Ottawa River to the lands of the interior and Great Lakes. Many missionaries, coureurs de bois and voyageurs passed by Ottawa, such as Jesuit martyr Jean de Brébeuf in 1634, on his way to the Hurons, Groseilliers in 1654,[16] Radisson,[16] and in the 1700s explorers La Vérendrye (who made four trips west in the 1730s and 1740s),[17] and later Alexander Mackenzie,[18] Joseph Frobisher and Simon McTavish.[17][19] Nicholas Gatineau also traded using the nearby Gatineau River.

The Algonquin were not the only people in present-day Ontario. During the 17th century, the Algonquians and Hurons fought a bitter war against the Iroquois. Champlain's travels brought him to Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay to the center of Huron country near Lake Simcoe. During these voyages, Champlain aided the Hurons in their battles against the Iroquois Confederacy. As a result, the Iroquois would become enemies of the French and be involved in multiple conflicts (known as the French and Iroquois Wars) until the signing of the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701.

Historical context prior to settlement

The 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France in North America. France ceded nearly all its New France colonies to Britain, after its loss of first Quebec City on the Plains of Abraham, and later Montreal. Consequently, areas west of Montreal began receiving many English-speaking settlers from Great Britain. Populations in Eastern Ontario also increased following the American Revolution's 1776 Declaration of Independence. Many United Empire Loyalists migrated to Canada, assisted by Britain, which granted them 200 acres (81 ha) of land and other items with which to rebuild their lives.

The Constitutional Act of 1791, established Upper Canada and Lower Canada which would last from December 26, 1791 to February 10, 1841. By this time two culturally distinct regions were forming; Loyalist Protestant American settlers and British immigrants in Upper Canada and a French-speaking Catholic population of Lower Canada. This essentially meant that the creation of the two solitudes led to the bisecting of the Algonquin Nation. Upper Canada had its own legislature and was administered by a lieutenant-governor (starting with John Graves Simcoe). Its capital was settled by 1796 in York, in present-day Toronto, a choice which was influenced by the threat of attack by the Americans, which also was a factor initiating the construction of the Rideau Canal. By the time settlement started near Ottawa, there were two principal local areas, Nepean Township west of the Rideau River and Gloucester Township to the east. Though not yet named, they were formed in 1793.[20]

Although the War of 1812 gave Upper Canada some confidence in its ability to defend itself against American intrusion, the threat remained. This led directly to the creation of the military settlements such as Perth, Ontario and the settling of some military regiment families (such as the 100th Regiment of Foot (Prince Regent's County of Dublin Regiment) at Richmond, Ontario).[21] By the time of Bytown's founding, Kingston, Ontario, located on the eastern shores of Lake Ontario south-west of Ottawa, had become a naval base of 2849 inhabitants, York's population was 1677,[22] Perth, 1500, and Brockville, another Eastern Ontario town had a population which was nearing 1000. In Lower Canada, Montreal and Quebec City were far larger, each having 22,000 inhabitants.[22]

Settlement

Early settlers

.jpg)

The first major settlement near Ottawa was founded by Philemon Wright, a New Englander from Woburn, Massachusetts who, on March 7, 1800,[23] arrived with his own and five other families along with twenty-five labourers.[5] They started an agricultural community called Wright's Town (now Gatineau, Quebec) on the north bank of the Ottawa River at the Chaudière Falls.[23] Food crops were not sufficient to sustain the community and Wright began harvesting trees as a cash crop when he determined that he could transport timber by river from the Ottawa Valley to the Montreal and Quebec City markets, and onward to Europe. His first raft of squared timber and sawed lumber arrived in Quebec City in 1806.[24] It was from this location that much of the future settlement on the south shore was facilitated. By this time, land on the Ottawa side of the river had already been surveyed and land grants were being issued.[25][26]

In 1818,[27] a settlement was formed at Richmond Landing, in present-day LeBreton Flats, while Richmond Road, Ottawa's first thoroughfare was being built.[28] Families of the English soldiers who came to create the settlement of Richmond stayed for months at this location which had had a store since 1809 erected by Jehiel Collins, who is credited as the first settler of what would become Bytown.[29][30] In the intervening years, the area would see such settlers as Braddish Billings, Abraham Dow, Ira Honeywell, John LeBreton. and original owner of much of Ottawa's early lands, Nicholas Sparks. Another major landholder was Lieutenant-Colonel John By, who oversaw the construction of the Rideau Canal.

Rideau Canal and growth of Bytown

The first European survey of the Rideau Route, part of an indigenous canoe route that connected the Ottawa River to the St. Lawrence River at Gananoque, was conducted by Lt. Gershom French in 1783. On October 2, 1783, his survey party camped on the shores of the Rideau River at the head of the portage from the Ottawa River that led around Rideau Falls. He described the area as "the soil everywhere good and deep, timbered with Maple, Elm and Butternut".[31] The War of 1812 made evident the need for a safe military supply route from Montreal to Kingston so the Rideau Route was surveyed for the purposes of a canal, in 1816 by Royal Engineer Joshua Jebb and in 1823-24 by civil surveyor Samuel Clowes. In 1826, Lieutenant-Colonel John By was appointed to oversee its construction and he hired contractors that included Philemon Wright, who supplied much of the stone, mortar and labour, Thomas McKay, a mason, and staff such as John MacTaggart and Thomas Burrowes, surveyor,[32] (Burrowes' created many paintings of early Bytown.) The Governor General George Ramsay, the Earl of Dalhousie took a great interest in the construction of the canal, as well as in establishing a settlement in the area. On September 26, 1826,[33] Colonel By and Dalhousie had agreed that the canal's entrance was to be at Entrance Bay (its current location), and along with a letter authorizing Colonel By to divide the town into lots,[34] marked the origins[33][35] of what was to become the town of Bytown.

Dalhousie's letter stated in part: "I take this opportunity of meeting you here to place in your hands a Sketch Plan of several Lots of Lands, which I thought advantageous to purchase for the use of Government, when this Canal was spoken of, as likely to be carried into effect, this not only contains the site for the Head Locks, but they offer a valuable locality for a considerable Village or Town, for the lodging of Artificers and other necessary Essentials, in so great a Work. I would propose that these be correctly surveyed, laid out in lots of 2 or so Acres, to be granted according to the means of settlers and to pay a Government rent of 2/6 per acre annually."[36]

By set up his base of operations in Wright's Town, and began construction of the Union Bridge[34] as a link to the new town. The Royal Sappers and Miners were employed in 1827 for the canal's construction, which began at three separate places, one of them being the site of the locks in Ottawa.[37] The workers were eventually moved into three barracks on today's Parliament Hill, which was then known as Barracks Hill. In 1827, Sappers Bridge connecting the Upper Town (west of the canal) and Lower Town (east of the canal) was built over the Rideau Canal.

The Victoria Brewery was established in 1829, by John Rochester, senior, and James Rochester, in the brewing of ale and porter. By 1866, it was conducted on Richmond Road, by John Rochester, junior.[38] The Chaudiere Brewery, which was established in 1858, was carried on by Parris & Smith by 1865. By 1866, Mr. Sterling operated a brewery at the foot of Rideau Locks while Dr. Doyle operated a brewery on Sussex Street.[39]

A steady stream of Irish immigration to Eastern Ontario (already well underway) in the next few decades,[40] along with French Canadians who crossed over from Quebec, provided the bulk of workers involved in the Rideau Canal project and the timber trade.[41] The canal was dubbed the Rideau Canal when it was finally completed in 1832. Colonel By laid out the town, most of his original street plans remain today.

To manufacture carriages and waggons, Peter Dufour established a carriage works in 1832; The Royal Carriage Factory was established in 1840, by George Humphries; and Wm. Stockdale & Brother's, on Rideau street, was established in 1854. Perkins' Foundry, on Sparks street, was established in 1840, by Lyman Perkins to manufacture steam engines, boilers and mill machinery; The City Foundry was established in 1848, by T. M. Blasdell to manufacture Mill machinery and agricultural implements. James McCullough, established a tannery in 1860 to turn out leather.[38]

Former Bytown mayor and cabinet minister, Richard William Scott recalled that in early 1850,

Neither Wellington, nor the streets south of it, between Elgin and Bank, had been laid out. Sussex was the business thoroughfare, and lots on it and the western ends of Rideau, George, and parallel streets, as far north as St. Patrick Street, commanded the best values. Wellington west of Bank, to Bay Street, was fairly well built up. The Le Breton Flats, extending north-westerly from Pooley's Bridge (in the vicinity of the Water Works building) contained a number of scattered houses.[42]

The Timber trade spurred the growth of Bytown, and it saw an influx of immigrants, and later entrepreneurs hoping to profit from the squared timber that would be floated down the Ottawa River to Quebec.[24][43] Bytown had seen some trouble in the early days, first with the Shiners' War in 1835 to 1845,[44] and the Stony Monday Riot in 1849.[45]

City of Ottawa

The St Lawrence and Ottawa Railway and Bytown and Prescott Railway linked the town to the outside world in 1854,[1] after a lot of expense and later huge losses by the city.[46] Bytown, now no longer a town, was renamed and the City of Ottawa was incorporated seven days later on January 1, 1855. Though the suggestion to give the city an aboriginal name had been published as early as 1844, Mayor Turgeon and Municipal Council proposed the name Ottawa to mark the 200th anniversary of the Ottawa people employing the river once again to come to Montreal for trade reasons.[47] The river had been unused for about 5 years for fear of attack but a 1654 truce with the Iroquois allowed its reuse.[47] While the event itself was not highly significant, it gave the name a historical context.

In 1841, Upper Canada ceased to exist as present day southern Quebec joined present day southern Ontario in the Province of Canada. The capital of Upper Canada had alternated between several cities for a while, and in 1857, Queen Victoria was asked to choose a more permanent location. Among the influences of her decision were defense concerns, as well as a location that would be somewhat centralized, and she chose Ottawa (see: History of Parliament Hill).

The "Ottawa Citizen" was originally established in 1844 as the "By town Packet" [38]

The sawed lumber industry supplanted the squared timber trade around the time Ottawa was incorporated when an influx of mostly American lumber barons decided that more money could be made if the timber was actually sawed. Mills began to be constructed; some of Canada's largest sawmills were located near the Chaudière Falls. Notable lumber barons in this area were Henry Franklin Bronson and John Rudolphus Booth. The lumber industry contributed to Ottawa's growth, and evidence of it is practically nonexistent today. The major portion of this industry lasted until shortly after the turn of the century, the decline being caused by decreased markets for lumber due to the switch to steel, Britain no longer subsidizing the market, and reduced supplies of uncut timber. During a time of stagnation in manufacturing and a decrease in the city's industrialization, the city would see new government departments being formed and large increases in public service employment following 1900.[48]

Between 1860 and 1876, construction of the parliament buildings took place on Parliament Hill. In 1867, the Provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada ceased to exist and were replaced with the provinces of Quebec and Ontario. Upon formation they united with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in Canadian Confederation. Legislation enacted in 1870 as "An Act respecting certain Works on the Ottawa River"[49] remains in effect to this day and mandates that the River and "all canals or other cuttings for facilitating such navigation, and all dams, slides, piers, booms, embankments and other works of what kind or nature soever in the channel or waters of the said River" fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Parliament at Ottawa, which now delegates this responsibility to the Minister of Public Works and Government Services.

The Ottawa Academy and Young Ladies' Seminary was established on Sparks Street in 1861.[39]

Messrs. Nordhemier & Co. established an agency in 1866 for all kinds of music and musical instruments, under the management of J. L. Orille & Son. Magdalen Asylum, run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd was established as a religious and charitable society in 1866 on Ottawa street between Gloucester and Chapel.[38]

On April 7, 1868, Thomas D'Arcy McGee, a Father of Confederation and Member of Parliament, was assassinated outside Mrs. Trotter's boarding house on Sparks Street between Metcalfe and O'Connor.[50] Yesterday's Restaurant currently stands at the location. On February 11, 1869, Patrick J. Whelan was publicly hanged at the Gaol on Nicholas Street.[50] It was the last public hanging in Canada.

Expansion into a major Canadian city

A vast public transportation network was started when Thomas Ahearn founded the Ottawa Electric Railway Company in 1893, replacing a horsecar system which began in 1870.[51] This private enterprise eventually provided heated streetcar service covering areas such as Brittania, Westboro, The Glebe, Rockcliffe Park and Old Ottawa South.[51]

Ottawa became part the transcontinental rail network on June 28, 1886, when Pacific Express connected it to Hull, Quebec (now Gatineau) and then onto Lachute, Quebec via the Prince of Wales Bridge.[52] For years, Ottawa was crisscrossed by the railways of several companies which had stations such as the Bytown and Prescott Railway in New Edinburgh, Broad Street in Lebreton Flats, and two others.[53] A downtown central station was first created in 1895 through John Rudolphus Booth's Canada Atlantic Railway. The site was later used for Union Station, which opened in June 1912 to little fanfare, since Grand Trunk Railway general manager Charles Hays perished in the Titanic disaster two months previously.[54] Though removed in 1966, the tracks had led along the east side of the canal towards downtown to Union Station, then alongside Chateau Laurier running to the Alexandra (Interprovincial) Bridge.

The Hull-Ottawa fire of 1900 destroyed two thirds of Hull, including 40 per cent of its residential buildings and most of its largest employers along the waterfront.[55] The fire also spread across the Ottawa River and destroyed about one fifth of Ottawa from the Lebreton Flats south to Booth Street and down to Dow's Lake.[56]

The Centre Block of the Parliament buildings were destroyed by fire on February 3, 1916.[57] The House of Commons and Senate were temporarily relocated to the recently constructed Victoria Memorial Museum, now the Canadian Museum of Nature.[58] A new Centre Block was completed in 1922, the centrepiece of which is a dominant Gothic revival-styled structure known as the Peace Tower located on Wellington Street.[59]

Confederation Square was created in the late 1930s, and Canada's National War Memorial was erected. It used lands that once contained the prestigious Russell House hotel, the Russell Theatre, and old City Hall, all which succumbed to fire, and the old post office and Knox Presbyterian Church were demolished. A new Central Post Office was erected facing the memorial.

Ottawa's industrial appearance was vastly changed due to the 1940s Greber Plan. Later powers were given by an act of Parliament to the newly formed National Capital Commission (NCC) to attain ownership of lands, and effect vast changes. Some of the results of these were the National Capital Greenbelt, expropriation of areas in downtown, the removal of large industrial areas, the removal of downtown railway tracks, the relocation of the train station out of downtown, and the creation and maintenance of areas that would provide the nation's capital with a more attractive appearance.

Collaboration between the city and NCC's predecessor, the Federal District Commission also led to major water and sewer projects, the construction of the Queensway which had been the old GTR/CNR right of way, several bridges, expansion of Carling Avenue, and the offer of F.D.C. land at Green Island (near Rideau Falls) to create city hall, opened in 1958.[60] Until then, the city had been without a permanent building for around 17 years. It was in use until 2000, when Ottawa City Hall occupied the former headquarters of the municipality.[60]

In the 1960s and 1970s, a building boom vastly changed Ottawa's skyline. Ottawa became one of Canada's largest high tech cities and was nicknamed Silicon Valley North. By the 1980s, Bell Northern Research (later Nortel) employed thousands, and large federally assisted research facilities such as the National Research Council contributed to an eventual technology boom. The early adopters led to offshoot companies such as Newbridge Networks, Mitel and Corel. Other large companies specializing in computer software and electronics infrastructures formed about this time, but by 2001, huge losses started being incurred. The industry continues today, but has been changed quite a bit.

Ottawa's city limits had been increasing over the years, but it acquired the most territory on January 1, 2001, when it amalgamated all the municipalities of the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton into one single city. Regional Chair Bob Chiarelli was elected as the new city's first mayor in the 2000 municipal election, defeating Gloucester mayor Claudette Cain. The city now not only includes former cities of Vanier, Nepean, Kanata and suburbs Orleans, Ontario and others, but now has many farms within its city limits.

The city's growth led to strains on the public transit system and to bridges. On October 15, 2001, a light rail transit (LRT) was introduced, the O-Train, which connected downtown Ottawa to the southern suburbs via Carleton University. Much political debate about the expansion of light rail dominated civic politics throughout the next decade. The vote to extend the O-Train Trillium Line, and to replace it with an electric tram system was a major issue in the 2006 municipal elections where Chiarelli was defeated to businessman Larry O'Brien. The new council changed their minds on light rail expansion, sparking much legal controversy. Plans were later created to establish a series of light rail stations from the east side of the city into downtown, and for using a tunnel in the downtown core. Truck traffic problems created much debate about a future east end bridge ("interprovincial crossing") linking Ottawa to Gatineau and an ongoing study was started in 2006.[61][62]

In 2001, the city banned smoking in public bars and restaurants. After much debate, Ottawa City Council voted against a motion to ban the cosmetic use of pesticides in 2005. Mayor Larry O'Brien experienced ongoing legal troubles during his tenure and was defeated in the 2010 municipal elections by former mayor Jim Watson.

In 2002, Ottawa was granted its second Canadian Football League (CFL) franchise, the Ottawa Renegades. The team would fold after just four seasons. In 2007, part of the south side stands at Frank Clair Stadium was demolished, sparking ideas about the site's future. In 2010, city council voted to renovate the stadium and to redevelop all of Lansdowne Park. The city was also awarded a CFL franchise that began play in 2014 called the Ottawa Redblacks. In 2014, the city was awarded a Can-AM Baseball franchise and the Ottawa Champions (www.OttawaChampions.com) began play on May 22, 2015 at the Ottawa Stadium (now named the Raymond Chabot Grant Thorton or RCGT Park)

See also

- Timeline of Ottawa history

- Ottawa River

- Ottawa River timber trade

- List of people from Ottawa

- List of municipalities in Ontario

References

- 1 2 3 The province of Ontario gazetteer and directory. H. McEvoy Editor and Compiler, Toronto : Robertson & Cook, Publishers, 1869

- ↑ Haig 1982.

- ↑ William J. Miller (2015). Geology: The Science of the Earth's Crust (Illustrations). P. F. Collier & Son Company. p. 37. GGKEY:Y3TD08H3RAT.

- ↑ McMillan & Yellowhorn 2004, p. 103.

- 1 2 Taylor 1986, p. 11.

- ↑ "Settlement Along the Ottawa River" (PDF). Ottawa River Heritage Designation Committee (Ontario Ministry of Culture). 2008. p. 1. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- 1 2 Hessel 1987, p. 10.

- ↑ Shaw 1998, p. 1.

- ↑ Hessel 1987, pp. 2, 10.

- ↑ Douglas 2003, p. 88.

- ↑ Matthews 1987, p. 82.

- ↑ The inscription 'Sault' means waterfall or rapids in early French

- ↑ Woods 1980, p. 5.

- ↑ Brault 1946, pp. 38,39.

- ↑ Legget 1986, p. 36.

- 1 2 Greening 1961, p. 5.

- 1 2 Haig 1975, p. 46.

- ↑ "The Ottawa River — Route to the Interior – National Capital Commission ::". Canadascapital.gc.ca. 2005-12-05. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- ↑ Mika 1982, p. 12.

- ↑ Woods 1980, p. 31.

- ↑ Schrauwers 2009, p. 44.

- 1 2 Legget 1986, p. 23.

- 1 2 Lee 2006, p. 16.

- 1 2 Van de Wetering 1997, p. 11.

- ↑ Mika 1982, pp. 18.

- ↑ Brault 1946, p. 304.

- ↑ Brault 1946, p. 55.

- ↑ Haig 1975, p. 53.

- ↑ Haig 1975, p. 50.

- ↑ Woods 1980.

- ↑ Watson, Ken W. (2007). The Rideau Route, Exploring the Pre-Canal Waterway. Elgin: Ken W. Watson. p. 75.

- ↑ Mika 1982, p. 50.

- 1 2 Brault 1946, p. 48.

- 1 2 Mika 1982.

- ↑ Haig 1975, p. 34.

- ↑ Watson, Ken W. (2000). A History of the Rideau Lockstations. Smiths Falls: Friends of the Rideau. p. 12.

- ↑ Pentland 1981, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 Ottawa City and counties of Carleton and Russell Directory, 1866-7

- 1 2 Mitchell & Co's County of Carleton and Ottawa City Directory for 1864–5; Toronto: W.C. Chewett & Co, 1864

- ↑ Keshen & St-Onge 2001, p. 226.

- ↑ Pentland 1981, p. 120.

- ↑ Scott 1911.

- ↑ Lee 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ "The Shiners' War" (PDF). Workers' Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Martin 1997, p. 22.

- ↑ Brault 1946, p. 190.

- 1 2 Brault 1946, p. 19.

- ↑ Taylor 1986, p. 120.

- ↑ "An Act respecting certain Works on the Ottawa River" (S.C. 1870, c. 24)

- 1 2 Woods 1980, p. 140.

- 1 2 Van de Wetering 1997, p. 28.

- ↑ "Ottawa History – 1886–1890". Bytown Museum. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- ↑ Van de Wetering 1997, p. 123.

- ↑ Van de Wetering 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ "Report of the Ottawa and Hull Fire Relief Fund, 1900, Ottawa." (PDF). The Rolla L. Crain Co (Archive CD Books Canada). December 31, 1900. pp. 5–12. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ↑ Van de Wetering 1997, pp. 57.

- ↑ Hale 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ Mullington 2005, p. 120.

- ↑ Reader's Digest Association (Canada)2004, p. 40.

- 1 2 Taylor 1986, pp. 186–194.

- ↑ "Interprovincial Crossings – Liaisons interprovinciales – Home". Ncrcrossings. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ↑ "City of Ottawa – Interprovincial Bridges". City of Ottawa. 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- Bibliography

- Bond, Courtney C. J. (1984), Where Rivers Meet: An Illustrated History of Ottawa, Windsor Publications, ISBN 0-89781-111-9

- Brault, Lucien (1946), Ottawa Old and New, Ottawa historical information Institute, OCLC 2947504

- Bumsted, J. m. (1998), A history of the Canadian peoples, Toronto: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-541200-1

- Martin, Carol (1997), Ottawa: a colourguide, Formac Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-88780-396-3

- Champlain, Samuel de, Charles-Honoré Cauchon Laverdière (1870), Œuvres de Champlain: Les voyages dv sievr de..., Seconde édition, Tome III, Québec: Université Laval, Open library OL18946744M, retrieved 28 August 2011

- Conroy, Peter (2002), Our Canal: the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, General Store Pub. House, ISBN 1-894263-63-4

- Dodwell, Henry (1929), The Cambridge history of the British Empire, CUP Archive, GGKEY:RPCX9953HTH, retrieved 27 May 2011

- Douglas, Gail (2003), Étienne Brûlé: The Mysterious Life and Times of an Early Canadian Legend, Canmore, Alberta: Altitude Publishing Canada, ISBN 1-55153-961-6

- Finnigan, Joan (1981). Giants of Canada's Ottawa Valley. GeneralStore PublishingHouse. ISBN 978-0-919431-00-3.

- Greening, W. e. (1961), The Ottawa, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, OCLC 25441343

- Haig, Robert (1975), Ottawa: City of the Big Ears, Ottawa: Haig and Haig Publishing Co.

- Hessel, Peter D. K. (1987), The Algonkin Tribe, Arnprior, Ontario: Kichesippi Books, ISBN 0-921082-01-0

- Hill, Hamnett P. (1919), Robert Randall and the Le Breton Flats, Ottawa: James Hope and Sons, OCLC 7654867

- Keshen, Jeff; St-Onge, Nicole (2001), Ottawa: Making a Capital, Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, ISBN 0-7766-0521-6

- Lee, David (2006), Lumber kings & shantymen : logging and lumbering in the Ottawa Valley, James Lorimer & Company, ISBN 978-1-55028-922-0

- Legget, Robert (1986), Rideau Waterway, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-6591-0

- MacKay, Robert W. S. (1851), The Canada Directory, Montreal: John Lovell

- Matthews, Geoffrey J. (1987), Historical atlas of Canada, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-2495-4

- McMillan, Alan Daniel; Yellowhorn, Eldon (2004), First peoples in Canada, Douglas & McIntyre, ISBN 978-1-55365-053-9, retrieved 8 July 2011

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1982), Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville, Ont: Mika Publishing Company, ISBN 0-919303-60-9

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1985), The Shaping of Ontario: From Exploration to Confederation, Belleville, Ont: Mika Publishing Company, ISBN 0-919303-93-5

- Mullington, Dave (2005), Chain of office: biographical sketches of the early mayors of Ottawa (1847–1948), General Store Publishing House, ISBN 978-1-897113-17-2, retrieved 27 May 2011

- Pentland, H. Clare (1981), Labour and capital in Canada, 1650–1860, James Lorimer & Company, ISBN 978-0-88862-378-2, retrieved 27 May 2011

- Reader's Digest Association (Canada) (2004), The Canadian atlas: our nation, environment and people, Reader's Digest Association (Canada), ISBN 978-1-55365-082-9, retrieved 27 May 2011

- Scott, R. w. (1911), Recollections of Bytown, Ottawa: Mortimer Press

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009), Union is strength: W.L. Mackenzie, the Children of Peace and the emergence of joint stock democracy in Upper Canada, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-9927-3, retrieved 27 May 2011

- Shaw, S. Bernard (1998), Lake Opeongo: Untold Stories of Algonquin Park's Largest Lake, General Store Publishing House, ISBN 978-1-896182-82-7

- Taylor, John H. (1986), Ottawa: An Illustrated History, J. Lorimer, ISBN 978-0-88862-981-4

- Van de Wetering, Marion (1997), An Ottawa album: glimpses of the way we were, Dundurn Press Ltd., ISBN 978-0-88882-195-9

- Woods, Shirley E. Jr. (1980), Ottawa: The Capital of Canada, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-14722-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Ottawa. |

- History of Ottawa – City of Ottawa

- Ancient history of the Ottawa Valley – Canadian Museum of Civilization

- History of Ottawa – Bytown Museum

- History of the canal – Virtual Museum of Canada

- One Room Schoolhouses in Ottawa