History of Canada

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Canada |

|---|

|

| Year list / Timeline |

| Topics |

| Research |

| Portal |

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Canada has been inhabited for millennia by distinctive groups of Aboriginal peoples, with distinct trade networks, spiritual beliefs, and styles of social organization. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first European arrivals and have been discovered through archaeological investigations. Various treaties and laws have been enacted between European settlers and the Aboriginal populations.

Beginning in the late 15th century, French and British expeditions explored, and later settled, along the Atlantic Coast. France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America to Britain in 1763 after the Seven Years' War. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the British Empire, which became official with the Statute of Westminster of 1931 and completed in the Canada Act of 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the British parliament.

Over centuries, elements of Aboriginal, French, British and more recent immigrant customs have combined to form a Canadian culture. Canadian culture has also been strongly influenced by its linguistic, geographic and economic neighbour, the United States. Since the conclusion of the Second World War, Canadians have supported multilateralism abroad and socioeconomic development domestically. Canada currently consists of ten provinces and three territories and is governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state.

Pre-colonization

Aboriginal peoples

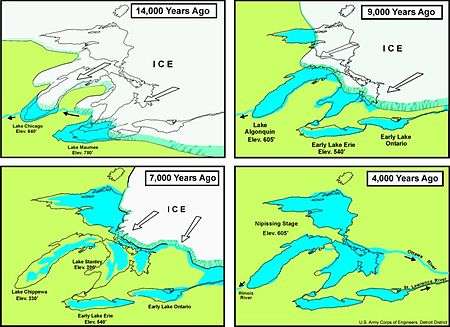

Archeological and Aboriginal genetic evidence indicate that North and South America were the last continents into which humans migrated.[1] During the Wisconsin glaciation, 50,000–17,000 years ago, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge (Beringia), from Siberia into northwest North America.[2] At that point, they were blocked by the Laurentide ice sheet that covered most of Canada, confining them to Alaska and the Yukon for thousands of years.[3] The exact dates and routes of the peopling of the Americas are the subject of an ongoing debate.[4][5] By 16,000 years ago the glacial melt allowed people to move by land south and east out of Beringia, and into Canada.[6] The Queen Charlotte Islands, Old Crow Flats, and Bluefish Caves contain some of the earliest Paleo-Indian archaeological sites in Canada.[7][8][9] Ice Age hunter-gatherers of this period left lithic flake fluted stone tools and the remains of large butchered mammals.

The North American climate stabilized around 8000 BCE (10,000 years ago). Climatic conditions were similar to modern patterns; however, the receding glacial ice sheets still covered large portions of the land, creating lakes of meltwater.[10] Most population groups during the Archaic periods were still highly mobile hunter-gatherers.[11] However, individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally; thus with the passage of time, there is a pattern of increasing regional generalization (i.e.: Paleo-Arctic, Plano and Maritime Archaic traditions).[11]

The Woodland cultural period dates from about 2000 BCE to 1000 CE and includes the Ontario, Quebec, and Maritime regions.[12] The introduction of pottery distinguishes the Woodland culture from the previous Archaic-stage inhabitants. The Laurentian-related people of Ontario manufactured the oldest pottery excavated to date in Canada.[13]

The Hopewell tradition is an Aboriginal culture that flourished along American rivers from 300 BCE to 500 CE. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell Exchange System connected cultures and societies to the peoples on the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario.[14] Canadian expression of the Hopewellian peoples encompasses the Point Peninsula, Saugeen, and Laurel complexes.[15]

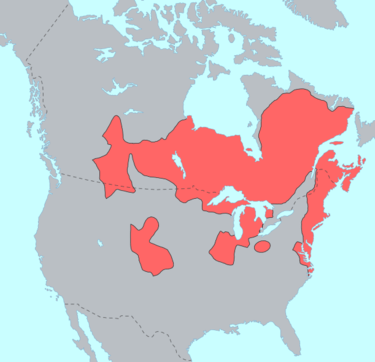

The eastern woodland areas of what became Canada were home to the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. The Algonquian language is believed to have originated in the western plateau of Idaho or the plains of Montana and moved eastward,[16] eventually extending all the way from Hudson Bay to what is today Nova Scotia in the east and as far south as the Tidewater region of Virginia.[17]

Speakers of eastern Algonquian languages included the Mi'kmaq and Abenaki of the Maritime region of Canada and likely the extinct Beothuk of Newfoundland.[18][19] The Ojibwa and other Anishinaabe speakers of the central Algonquian languages retain an oral tradition of having moved to their lands around the western and central Great Lakes from the sea, likely the east coast.[20] According to oral tradition, the Ojibwa formed the Council of Three Fires in 796 CE with the Odawa and the Potawatomi.[21]

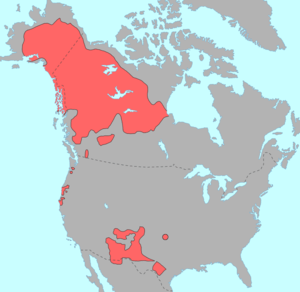

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) were centred from at least 1000 CE in northern New York, but their influence extended into what is now southern Ontario and the Montreal area of modern Quebec.[22] The Iroquois Confederacy, according to oral tradition, was formed in 1142 CE.[23][24] On the Great Plains the Cree or Nēhilawē (who spoke a closely related Central Algonquian language, the plains Cree language) depended on the vast herds of bison to supply food and many of their other needs.[25] To the northwest were the peoples of the Na-Dene languages, which include the Athapaskan-speaking peoples and the Tlingit, who lived on the islands of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia. The Na-Dene language group is believed to be linked to the Yeniseian languages of Siberia.[26] The Dene of the western Arctic may represent a distinct wave of migration from Asia to North America.[26]

The Interior of British Columbia was home to the Salishan language groups such as the Shuswap (Secwepemc), Okanagan and southern Athabaskan language groups, primarily the Dakelh (Carrier) and the Tsilhqot'in.[27] The inlets and valleys of the British Columbia Coast sheltered large, distinctive populations, such as the Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth, sustained by the region's abundant salmon and shellfish.[27] These peoples developed complex cultures dependent on the western red cedar that included wooden houses, seagoing whaling and war canoes and elaborately carved potlatch items and totem poles.[27]

In the Arctic archipelago, the distinctive Paleo-Eskimos known as Dorset peoples, whose culture has been traced back to around 500 BCE, were replaced by the ancestors of today's Inuit by 1500 CE.[28] This transition is supported by archaeological records and Inuit mythology that tells of having driven off the Tuniit or 'first inhabitants'.[29] Inuit traditional laws are anthropologically different from Western law. Customary law was non-existent in Inuit society before the introduction of the Canadian legal system.[30]

European contact

There are reports of contact made before the 1492 voyages of Christopher Columbus and the age of discovery between First Nations, Inuit and those from other continents. The Norse, who had settled Greenland and Iceland, arrived around the year 1000 and built a small settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows at the northernmost tip of Newfoundland (carbon dating estimate 990 – 1050 CE)[31] L'Anse aux Meadows is also notable for its connection with the attempted colony of Vinland established by Leif Erikson around the same period or, more broadly, with Norse exploration of the Americas.[31][32]

Under letters patent from King Henry VII of England, the Italian John Cabot became the first European known to have landed in Canada after the time of the Vikings.[33] Records indicate that on 24 June 1497 he sighted land at a northern location believed to be somewhere in the Atlantic provinces.[34] Official tradition deemed the first landing site to be at Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, although other locations are possible.[35] After 1497 Cabot and his son Sebastian Cabot continued to make other voyages to find the Northwest Passage, and other explorers continued to sail out of England to the New World, although the details of these voyages are not well recorded.[36]

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, the Spanish Crown claimed it had territorial rights in the area visited by John Cabot in 1497 and 1498 CE.[37] However, Portuguese explorers like João Fernandes Lavrador would continue to visited the north Atlantic coast, which accounts for the appearance of "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.[38] In 1501 and 1502 the Corte-Real brothers explored Newfoundland (Terra Nova) and Labrador claiming these lands as part of the Portuguese Empire.[38][39] In 1506, King Manuel I of Portugal created taxes for the cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters.[40] João Álvares Fagundes and Pêro de Barcelos established fishing outposts in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia around 1521 CE; however, these were later abandoned, with the Portuguese colonizers focusing their efforts on South America.[41] The extent and nature of Portuguese activity on the Canadian mainland during the 16th century remains unclear and controversial.[42][43]

English America, New France and colonization 1534–1763

French interest in the New World began with Francis I of France, who in 1524 sponsored Giovanni da Verrazzano to navigate the region between Florida and Newfoundland in hopes of finding a route to the Pacific Ocean.[45] In 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed the land in the name of Francis I.[46] Earlier colonization attempts by Cartier at Charlesbourg-Royal in 1541, at Sable Island in 1598 by Marquis de La Roche-Mesgouez, and at Tadoussac, Quebec in 1600 by François Gravé Du Pont had failed.[47] Despite these initial failures, French fishing fleets began to sail to the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River, trading and making alliances with First Nations.[48]

In 1604, a North American fur trade monopoly was granted to Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Mons.[49] The fur trade became one of the main economic ventures in North America.[50] Du Gua led his first colonization expedition to an island located near the mouth of the St. Croix River. Among his lieutenants was a geographer named Samuel de Champlain, who promptly carried out a major exploration of the northeastern coastline of what is now the United States.[49] In the spring of 1605, under Samuel de Champlain, the new St. Croix settlement was moved to Port Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia).[51]

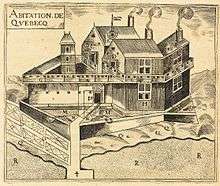

In 1608 Champlain founded what is now Quebec City, one of the earliest permanent settlements, which would become the capital of New France.[52] He took personal administration over the city and its affairs, and sent out expeditions to explore the interior.[53] Champlain himself discovered Lake Champlain in 1609. By 1615, he had travelled by canoe up the Ottawa River through Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay to the centre of Huron country near Lake Simcoe.[54] During these voyages, Champlain aided the Wendat (aka "Hurons") in their battles against the Iroquois Confederacy.[55] As a result, the Iroquois would become enemies of the French and be involved in multiple conflicts (known as the French and Iroquois Wars) until the signing of the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701.[56]

The English, led by Humphrey Gilbert, had claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, in 1583 as the first North American English colony by royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I.[57] In the reign of King James I, the English established additional colonies in Cupids and Ferryland, Newfoundland, and soon after established the first successful permanent settlements of Virginia to the south.[58] On September 29, 1621, a charter for the foundation of a New World Scottish colony was granted by King James to Sir William Alexander.[59] In 1622, the first settlers left Scotland. They initially failed and permanent Nova Scotian settlements were not firmly established until 1629 during the end of the Anglo-French War.[59] These colonies did not last long: in 1631, under Charles I of England, the Treaty of Suza was signed, ending the war and returning Nova Scotia to the French.[60] New France was not fully restored to French rule until the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[61] This led to new French immigrants and the founding of Trois-Rivières in 1634.[62]

During this period, in contrast to the higher density and slower moving agricultural settlement development by the English inward from the east coast of the colonies, New France's interior frontier would eventually cover an immense area with a thin network centred on fur trade, conversion efforts by missionaries, establishing and claiming an empire, and military efforts to protect and further those efforts.[63] The largest of these canoe networks covered much of present-day Canada and central present-day United States.[64]

After Champlain’s death in 1635, the Roman Catholic Church and the Jesuit establishment became the most dominant force in New France and hoped to establish a utopian European and Aboriginal Christian community.[65] In 1642, the Sulpicians sponsored a group of settlers led by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, who founded Ville-Marie, precursor to present-day Montreal.[66] In 1663 the French crown took direct control of the colonies from the Company of New France.[67]

Although immigration rates to New France remained very low under direct French control,[68] most of the new arrivals were farmers, and the rate of population growth among the settlers themselves had been very high.[69] The women had about 30 per cent more children than comparable women who remained in France.[70] Yves Landry says, "Canadians had an exceptional diet for their time."[70] This was due to the natural abundance of meat, fish, and pure water; the good food conservation conditions during the winter; and an adequate wheat supply in most years.[70] The 1666 census of New France was conducted by France's intendant, Jean Talon, in the winter of 1665–1666. The census showed a population count of 3,215 Acadians and habitants (French-Canadian farmers) in the administrative districts of Acadia and Canada.[71] The census also revealed a great difference in the number of men at 2,034 versus 1,181 women.[72]

Wars during the colonial era

By the early 1700s the New France settlers were well established along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River and parts of Nova Scotia, with a population around 16,000.[73] However new arrivals stopped coming from France in the proceeding decades,[74][75][76] resulting in the English and Scottish settlers in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and the southern Thirteen Colonies to vastly outnumber the French population approximately ten to one by the 1750s.[68][77] From 1670, through the Hudson's Bay Company, the English also laid claim to Hudson Bay and its drainage basin known as Rupert's Land establishing new trading posts and forts, while continuing to operate fishing settlements in Newfoundland.[78] French expansion along the Canadian canoe routes challenged the Hudson's Bay Company claims, and in 1686, Pierre Troyes led an overland expedition from Montreal to the shore of the bay, where they managed to capture a handful of outposts.[79] La Salle's explorations gave France a claim to the Mississippi River Valley, where fur trappers and a few settlers set up scattered forts and settlements.[80]

There were four French and Indian Wars and two additional wars in Acadia and Nova Scotia between the Thirteen American Colonies and New France from 1688 to 1763. During King William's War (1688 to 1697), military conflicts in Acadia included: Battle of Port Royal (1690); a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy (Action of July 14, 1696); and the Raid on Chignecto (1696) .[81] The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ended the war between the two colonial powers of England and France for a brief time.[82] During Queen Anne's War (1702 to 1713), the British Conquest of Acadia occurred in 1710,[83] resulting in Nova Scotia, other than Cape Breton, being officially ceded to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht including Rupert's Land, which France had conquered in the late 17th century (Battle of Hudson's Bay).[84] As an immediate result of this setback, France founded the powerful Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.[85]

Louisbourg was intended to serve as a year-round military and naval base for France's remaining North American empire and to protect the entrance to the St. Lawrence River. Father Rale's War resulted in both the fall of New France influence in present-day Maine and the British recognition of having to negotiate with the Mi'kmaq in Nova Scotia. During King George's War (1744 to 1748), an army of New Englanders led by William Pepperrell mounted an expedition of 90 vessels and 4,000 men against Louisbourg in 1745.[86] Within three months the fortress surrendered. The return of Louisbourg to French control by the peace treaty prompted the British to found Halifax in 1749 under Edward Cornwallis.[87] Despite the official cessation of war between the British and French empires with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle; the conflict in Acadia and Nova Scotia continued on as the Father Le Loutre's War.[88]

The British ordered the Acadians expelled from their lands in 1755 during the French and Indian War, an event called the Expulsion of the Acadians or le Grand Dérangement.[89] The "expulsion" resulted in approximately 12,000 Acadians being shipped to destinations throughout Britain's North America and to France, Quebec and the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue.[90] The first wave of the expulsion of the Acadians began with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755) and the second wave began after the final Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Many of the Acadians settled in southern Louisiana, creating the Cajun culture there.[91] Some Acadians managed to hide and others eventually returned to Nova Scotia, but they were far outnumbered by a new migration of New England Planters who were settled on the former lands of the Acadians and transformed Nova Scotia from a colony of occupation for the British to a settled colony with stronger ties to New England.[91] Britain eventually gained control of Quebec City and Montreal after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and Battle of Fort Niagara in 1759, and the Battle of the Thousand Islands and Battle of Sainte-Foy in 1760.[92]

Canada under British rule (1763–1867)

With the end of the Seven Years' War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763), France ceded almost all of its remaining territory in mainland North America, except for fishing rights off Newfoundland and the two small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon where its fishermen could dry their fish. France had already secretly ceded its vast Louisiana territory to Spain under the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762) in which King Louis XV of France had given his cousin King Charles III of Spain the entire area of the drainage basin of the Mississippi River from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. France and Spain kept the Treaty of Fontainebleau secret from other countries until 1764.[93] In return for acquiring Canada, Britain returned to France its most important sugar-producing colony, Guadeloupe, which the French at the time considered more valuable than Canada. (Guadeloupe produced more sugar than all the British islands combined, and Voltaire had notoriously dismissed Canada as "Quelques arpents de neige", "A few acres of snow").[94]

The new British rulers of Canada retained and protected most of the property, religious, political, and social culture of the French-speaking habitants, guaranteeing the right of the Canadiens to practice the Catholic faith and to the use of French civil law (now Quebec law) through the Quebec Act of 1774.[95] The Royal Proclamation of 1763 had been issued in October, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory.[96] The proclamation organized Great Britain's new North American empire and stabilized relations between the British Crown and Aboriginal peoples through regulation of trade, settlement, and land purchases on the western frontier.[96]

American Revolution and the Loyalists

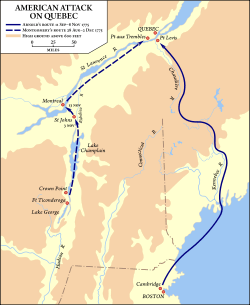

During the American Revolution, there was some sympathy for the American cause among the Acadians and the New Englanders in Nova Scotia.[97] Neither party joined the rebels, although several hundred individuals joined the revolutionary cause.[97][98] An invasion of Quebec by the Continental Army in 1775, with a goal to take Quebec from British control, was halted at the Battle of Quebec by Guy Carleton, with the assistance of local militias. The defeat of the British army during the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781 signaled the end of Britain's struggle to suppress the American Revolution.[99]

When the British evacuated New York City in 1783, they took many Loyalist refugees to Nova Scotia, while other Loyalists went to southwestern Quebec. So many Loyalists arrived on the shores of the St. John River that a separate colony—New Brunswick—was created in 1784;[100] followed in 1791 by the division of Quebec into the largely French-speaking Lower Canada (French Canada) along the St. Lawrence River and Gaspé Peninsula and an anglophone Loyalist Upper Canada, with its capital settled by 1796 in York, in present-day Toronto.[101] After 1790 most of the new settlers were American farmers searching for new lands; although generally favorable to republicanism, they were relatively non-political and stayed neutral in the War of 1812.[102]

The signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 formally ended the war. Britain made several concessions to the Americans at the expense of the North American colonies.[103] Notably, the borders between Canada and the United States were officially demarcated;[103] all land south of the Great Lakes, which was formerly a part of the Province of Quebec and included modern day Michigan, Illinois and Ohio, was ceded to the Americans. Fishing rights were also granted to the United States in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and on the coast of Newfoundland and the Grand Banks.[103] The British ignored part of the treaty and maintained their military outposts in the Great Lakes areas it had ceded to the U.S., and they continued to supply their native allies with munitions. The British evacuated the outposts with the Jay Treaty of 1795, but the continued supply of munitions irritated the Americans in the run-up to the War of 1812.[104]

Lower emphasizes the positive benefits of the Revolution for Americans, making them an energetic people, while for English Canada the results were negative:

[English Canada] inherited, not the benefits, but the bitterness of the Revolution. It got no shining scriptures out of it. It got little release of energy and no new horizons of the spirit were opened up. It had been a calamity, pure and simple.[105] To take the place of the internal fire that was urging Americans westward across the continent, there was only melancholy contemplation of things as they might have been and dingy reflection of that ineffably glorious world across the stormy Atlantic. English Canada started its life with as powerful a nostalgic shove backward into the past as the Conquest had given to French Canada: two little peoples officially devoted to counter-revolution, to lost causes, to the tawdry ideals of a society of men and masters, and not to the self-reliant freedom alongside of them.[105]

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the British, with the British North American colonies being heavily involved.[106] Greatly outgunned by the British Royal Navy, the American war plans focused on an invasion of Canada (especially what is today eastern and western Ontario). The American frontier states voted for war to suppress the First Nations raids that frustrated settlement of the frontier.[106] The war on the border with the United States was characterized by a series of multiple failed invasions and fiascos on both sides. American forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813, driving the British out of western Ontario, killing the Native American leader Tecumseh, and breaking the military power of his confederacy.[107] The war was overseen by British army officers like Isaac Brock and Charles de Salaberry with the assistance of First Nations and loyalist informants, most notably Laura Secord.[108]

The War ended with no boundary changes thanks to the Treaty of Ghent of 1814, and the Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817.[106] A demographic result was the shifting of the destination of American migration from Upper Canada to Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, without fear of Indian attacks.[106] After the war, supporters of Britain tried to repress the republicanism that was common among American immigrants to Canada.[106] The troubling memory of the war and the American invasions etched itself into the consciousness of Canadians as a distrust of the intentions of the United States towards the British presence in North America.[109]pp. 254–255

Rebellions and the Durham Report

The rebellions of 1837 against the British colonial government took place in both Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, a band of Reformers under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie took up arms in a disorganized and ultimately unsuccessful series of small-scale skirmishes around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.[110]

In Lower Canada, a more substantial rebellion occurred against British rule. Both English- and French-Canadian rebels, sometimes using bases in the neutral United States, fought several skirmishes against the authorities. The towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels, and Quebec City was isolated from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read the "Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada" to a crowd assembled at the town of Napierville in 1838.[111] The rebellion of the Patriote movement was defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burnt in reprisal.[111]

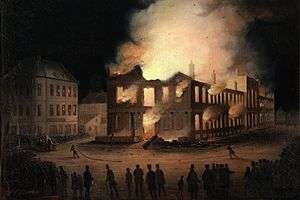

British Government then sent Lord Durham to examine the situation; he stayed in Canada only five months before returning to Britain and brought with him his Durham Report, which strongly recommended responsible government.[112] A less well-received recommendation was the amalgamation of Upper and Lower Canada for the deliberate assimilation of the French-speaking population. The Canadas were merged into a single colony, the United Province of Canada, by the 1840 Act of Union, and responsible government was achieved in 1848, a few months after it was accomplished in Nova Scotia.[112] The parliament of United Canada in Montreal was set on fire by a mob of Tories in 1849 after the passing of an indemnity bill for the people who suffered losses during the rebellion in Lower Canada.[113]

Between the Napoleonic Wars and 1850, some 800,000 immigrants came to the colonies of British North America, mainly from the British Isles, as part of the great migration of Canada.[114] These included Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances to Nova Scotia and Scottish and English settlers to the Canadas, particularly Upper Canada. The Irish Famine of the 1840s significantly increased the pace of Irish Catholic immigration to British North America, with over 35,000 distressed Irish landing in Toronto alone in 1847 and 1848.[115]

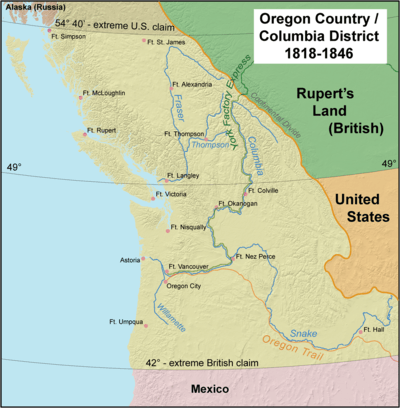

Pacific colonies

Spanish explorers had taken the lead in the Pacific Northwest coast, with the voyages of Juan José Pérez Hernández in 1774 and 1775.[116] By the time the Spanish determined to build a fort on Vancouver Island, the British navigator James Cook had visited Nootka Sound and charted the coast as far as Alaska, while British and American maritime fur traders had begun a busy era of commerce with the coastal peoples to satisfy the brisk market for sea otter pelts in China, thereby launching what became known as the China Trade.[117] In 1789 war threatened between Britain and Spain on their respective rights; the Nootka Crisis was resolved peacefully largely in favor of Britain, the much stronger naval power. In 1793 Alexander MacKenzie, a Canadian working for the North West Company, crossed the continent and with his Aboriginal guides and French-Canadian crew, reached the mouth of the Bella Coola River, completing the first continental crossing north of Mexico, missing George Vancouver's charting expedition to the region by only a few weeks.[118] In 1821, the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company merged, with a combined trading territory that was extended by a licence to the North-Western Territory and the Columbia and New Caledonia fur districts, which reached the Arctic Ocean on the north and the Pacific Ocean on the west.[119]

The Colony of Vancouver Island was chartered in 1849, with the trading post at Fort Victoria as the capital. This was followed by the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1853, and by the creation of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858 and the Stikine Territory in 1861, with the latter three being founded expressly to keep those regions from being overrun and annexed by American gold miners.[120] The Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands and most of the Stikine Territory were merged into the Colony of British Columbia in 1863 (the remainder, north of the 60th Parallel, became part of the North-Western Territory).[120]

Confederation

The Seventy-Two Resolutions from the 1864 Quebec Conference and Charlottetown Conference laid out the framework for uniting British colonies in North America into a federation.[121] They had been adopted by the majority of the provinces of Canada and became the basis for the London Conference of 1866, which led to the formation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867.[121] The term dominion was chosen to indicate Canada's status as a self-governing colony of the British Empire, the first time it was used about a country.[122] With the coming into force of the British North America Act (enacted by the British Parliament), the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federated kingdom in its own right.[123][124][125]

Federation emerged from multiple impulses: the British wanted Canada to defend itself; the Maritimes needed railroad connections, which were promised in 1867; British-Canadian nationalism sought to unite the lands into one country, dominated by the English language and British culture; many French-Canadians saw an opportunity to exert political control within a new largely French-speaking Quebec[109]pp. 323–324 and fears of possible U.S. expansion northward.[122] On a political level, there was a desire for the expansion of responsible government and elimination of the legislative deadlock between Upper and Lower Canada, and their replacement with provincial legislatures in a federation.[122] This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian Parti rouge in Lower Canada who favored a decentralized union in comparison to the Upper Canadian Conservative party and to some degree the French-Canadian Parti bleu, which favored a centralized union.[122][126]

Post-Confederation Canada 1867–1914

Expansion

Using the lure of the Canadian Pacific Railway, a transcontinental line that would unite the nation, Ottawa attracted support in the Maritimes and in British Columbia. In 1866, the Colony of British Columbia and the Colony of Vancouver Island merged into a single Colony of British Columbia; it joined the Canadian Confederation in 1871. In 1873, Prince Edward Island joined. Newfoundland—which had no use for a transcontinental railway—voted no in 1869, and did not join Canada until 1949.[127]

In 1873 John A. Macdonald (First Prime Minister of Canada) created the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) to help police the Northwest Territories.[128] Specifically the Mounties were to assert Canadian sovereignty over possible American encroachments into the sparsely populated land.[128]

The Mounties' first large-scale mission was to suppress the second independence movement by Manitoba's Métis, a mixed blood people of joint First Nations and European descent, who originated in the mid-17th century.[129] The desire for independence erupted in the Red River Rebellion in 1869 and the later North-West Rebellion in 1885 led by Louis Riel.[128][130] Suppressing the Rebellion was Canada's first independent military action. It cost about $5 million and demonstrated the need to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway. It guaranteed Anglophone control of the Prairies, and demonstrated the national government was capable of decisive action. However, it lost the Conservative Party most of their support in Quebec and led to permanent distrust of the Anglophone community on the part of the Francophones.[131]

In 1905 when Saskatchewan and Alberta were admitted as provinces, they were growing rapidly thanks to abundant wheat crops that attracted immigration to the plains by Ukrainians and Northern and Central Europeans and by settlers from the United States, Britain and eastern Canada.[132][133]

.jpg)

The Alaska boundary dispute, simmering since the Alaska purchase of 1867, became critical when gold was discovered in the Yukon during the late 1890s, with the U.S. controlling all the possible ports of entry. Canada argued its boundary included the port of Skagway. The dispute went to arbitration in 1903, but the British delegate sided with the Americans, angering Canadians who felt the British had betrayed Canadian interests to curry favour with the U.S.[134]

In the 1890s, legal experts codified a framework of criminal law, culminating in the Criminal Code, 1892.[135] This solidified the liberal ideal of "equality before the law" in a way that made an abstract principle into a tangible reality for every adult Canadian.[136] Wilfrid Laurier who served 1896–1911 as the Seventh Prime Minister of Canada felt Canada was on the verge of becoming a world power, and declared that the 20th century would "belong to Canada"[137]

Laurier signed a reciprocity treaty with the U.S. that would lower tariffs in both directions. Conservatives under Robert Borden denounced it, saying it would integrate Canada's economy into that of the U.S. and loosen ties with Britain. The Conservative party won the Canadian federal election, 1911.[138]

Development of Popular Culture

Canadian culture as it is understood today can be traced to its time period of westward expansion. Contributing factors include Canada's unique geography, climate, and cultural makeup. Being a cold country with long winter nights for most of the year, certain unique leisure activities developed in Canada during this period including hockey and lacrosse.[139][140][141] During this period the churches tried to steer leisure activities, by preaching against drinking and scheduling annual revivals and weekly club activities.[142] By 1930 radio played a major role in uniting Canadians behind their local or regional hockey teams. Play-by-play sports coverage, especially of ice hockey, absorbed fans far more intensely than newspaper accounts the next day. Rural areas were especially influenced by sports coverage.[143] Canadians in the 19th century came to believe themselves possessed of a unique "northern character," due to the long, harsh winters that only those of hardy body and mind could survive. This hardiness was claimed as a Canadian trait, and such sports as ice hockey and snowshoeing that reflected this were asserted as characteristically Canadian.[144] Outside the sports arena Canadians express the national characteristics of being peaceful, orderly and polite. Inside they scream their lungs out at ice hockey games, cheering the speed, ferocity, and violence, making hockey an ambiguous symbol of Canada.[145]

World wars and interwar years 1914–1945

First World War

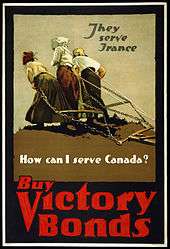

The Canadian Forces and civilian participation in the First World War helped to foster a sense of British-Canadian nationhood. The highpoints of Canadian military achievement during the First World War came during the Somme, Vimy, Passchendaele battles and what later became known as "Canada's Hundred Days".[146] The reputation Canadian troops earned, along with the success of Canadian flying aces including William George Barker and Billy Bishop, helped to give the nation a new sense of identity.[147] The War Office in 1922 reported approximately 67,000 killed and 173,000 wounded during the war.[148] This excludes civilian deaths in war-time incidents like the Halifax Explosion.[148]

Support for Great Britain during the First World War caused a major political crisis over conscription, with Francophones, mainly from Quebec, rejecting national policies.[149] During the crisis, large numbers of enemy aliens (especially Ukrainians and Germans) were put under government controls.[150] The Liberal party was deeply split, with most of its Anglophone leaders joining the unionist government headed by Prime Minister Robert Borden, the leader of the Conservative party.[151] The Liberals regained their influence after the war under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie King, who served as prime minister with three separate terms between 1921 and 1949.[152]

Woman suffrage

Women's political status without the vote was vigorously promoted by the National Council of Women of Canada from 1894 to 1918. It promoted a vision of "transcendent citizenship" for women. The ballot was not needed, for citizenship was to be exercised through personal influence and moral suasion, through the election of men with strong moral character, and through raising public-spirited sons.[153] The National Council position reflected its nation-building program that sought to uphold Canada as a White settler nation. While the woman suffrage movement was important for extending the political rights of White women, it was also authorized through race-based arguments that linked White women's enfranchisement to the need to protect the nation from "racial degeneration".[153]

Women did have a local vote in some provinces, as in Canada West from 1850, where women owning land could vote for school trustees. By 1900 other provinces adopted similar provisions, and in 1916 Manitoba took the lead in extending full woman's suffrage.[154] Simultaneously suffragists gave strong support to the prohibition movement, especially in Ontario and the Western provinces.[155][156]

The Military Voters Act of 1917 gave the vote to British women who were war widows or had sons or husbands serving overseas. Unionists Prime Minister Borden pledged himself during the 1917 campaign to equal suffrage for women. After his landslide victory, he introduced a bill in 1918 for extending the franchise to women. This passed without division, but did not apply to Quebec provincial and municipal elections. The women of Quebec gained full suffrage in 1940. The first woman elected to Parliament was Agnes Macphail of Ontario in 1921.[157]

Interwar

On the world stage

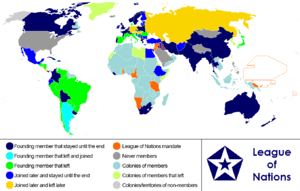

As a result of its contribution to Allied victory in the First World War, Canada became more assertive and less deferential to British authority. Convinced that Canada had proven itself on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden demanded that it have a separate seat at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. This was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by the United States, which saw such a delegation as an extra British vote. Borden responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men, a far larger proportion of its men, its right to equal status as a nation had been consecrated on the battlefield. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George eventually relented, and convinced the reluctant Americans to accept the presence of delegations from Canada, India, Australia, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and South Africa. These also received their own seats in the League of Nations.[158] Canada asked for neither reparations nor mandates. It played only a modest role at Paris, but just having a seat was a matter of pride. It was cautiously optimistic about the new League of Nations, in which it played an active and independent role.[159]

In 1923 British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, appealed repeatedly for Canadian support in the Chanak crisis, in which a war threatened between Britain and Turkey. Canada refused.[160] The Department of External Affairs, which had been founded in 1909, was expanded and promoted Canadian autonomy as Canada reduced its reliance on British diplomats and used its own foreign service.[161] Thus began the careers of such important diplomats as Norman Robertson and Hume Wrong, and future prime minister Lester Pearson.[162]

In 1931 the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster which gave each dominion the opportunity for almost complete legislative independence from London.[163] While Newfoundland never adopted the statute, for Canada the Statute of Westminster became its declaration of independence.[164]

Domestic affairs

In 1921 to 1926, William Lyon Mackenzie King's Liberal government pursued a conservative domestic policy with the object of lowering wartime taxes and, especially, cooling wartime ethnic tensions, as well as defusing postwar labour conflicts. The Progressives refused to join the government, but did help the Liberals defeat non-confidence motions. King faced a delicate balancing act of reducing tariffs enough to please the Prairie-based Progressives, but not too much to alienate his vital support in industrial Ontario and Quebec, which needed tariffs to compete with American imports. King and Conservative leader Arthur Meighen sparred constantly and bitterly in Commons debates.[165] The Progressives gradually weakened. Their effective and passionate leader, Thomas Crerar, resigned to return to his grain business, and was replaced by the more placid Robert Forke. The socialist reformer J. S. Woodsworth gradually gained influence and power among the Progressives, and he reached an accommodation with King on policy matters.[166]

In 1926 Prime Minister Mackenzie King advised the Governor General, Lord Byng, to dissolve Parliament and call another election, but Byng refused, the only time that the Governor General has exercised such a power. Instead Byng called upon Meighen, the Conservative Party leader, to form a government.[167] Meighen attempted to do so, but was unable to obtain a majority in the Commons and he, too, advised dissolution, which this time was accepted. The episode, the King–Byng Affair, marks a constitutional crisis that was resolved by a new tradition of complete non-interference in Canadian political affairs on the part of the British government.[168]

Great Depression

Canada was hard hit by the worldwide Great Depression that began in 1929. Between 1929 and 1933, the gross national product dropped 40% (compared to 37% in the US). Unemployment reached 27% at the depth of the Depression in 1933.[169] Many businesses closed, as corporate profits of $396 million in 1929 turned into losses of $98 million in 1933. Canadian exports shrank by 50% from 1929 to 1933. Construction all but stopped (down 82%, 1929–33), and wholesale prices dropped 30%. Wheat prices plunged from 78c per bushel (1928 crop) to 29c in 1932.[169]

Urban unemployment nationwide was 19%; Toronto's rate was 17%, according to the census of 1931. Farmers who stayed on their farms were not considered unemployed.[170] By 1933, 30% of the labour force was out of work, and one fifth of the population became dependent on government assistance. Wages fell as did prices. Worst hit were areas dependent on primary industries such as farming, mining and logging, as prices fell and there were few alternative jobs. Most families had moderate losses and little hardship, though they too became pessimistic and their debts become heavier as prices fell. Some families saw most or all of their assets disappear, and suffered severely.[171][172]

In 1930, in the first stage of the long depression, Prime Minister Mackenzie King believed that the crisis was a temporary swing of the business cycle and that the economy would soon recover without government intervention. He refused to provide unemployment relief or federal aid to the provinces, saying that if Conservative provincial governments demanded federal dollars, he would not give them "a five cent piece."[173] His blunt wisecrack was used to defeat the Liberals in the 1930 election. The main issue was the rapid deterioration in the economy and whether the prime minister was out of touch with the hardships of ordinary people.[174][175] The winner of the 1930 election was Richard Bedford Bennett and the Conservatives. Bennett had promised high tariffs and large-scale spending, but as deficits increased, he became wary and cut back severely on Federal spending. With falling support and the depression getting only worse, Bennett attempted to introduce policies based on the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in the United States, but he got little passed. Bennett's government became a focus of popular discontent. For example, auto owners saved on gasoline by using horses to pull their cars, dubbing them Bennett Buggies. The Conservative failure to restore prosperity led to the return of Mackenzie King's Liberals in the 1935 election.[176]

In 1935, the Liberals used the slogan "King or Chaos" to win a landslide in the 1935 election.[177] Promising a much-desired trade treaty with the U.S., the Mackenzie King government passed the 1935 Reciprocal Trade Agreement. It marked the turning point in Canadian-American economic relations, reversing the disastrous trade war of 1930–31, lowering tariffs, and yielding a dramatic increase in trade.[178]

The worst of the Depression had passed by 1935, as Ottawa launched relief programs such as the National Housing Act and National Employment Commission. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation became a crown corporation in 1936. Trans-Canada Airlines (the precursor to Air Canada) was formed in 1937, as was the National Film Board of Canada in 1939. In 1938, Parliament transformed the Bank of Canada from a private entity to a crown corporation.[179]

One political response was a highly restrictive immigration policy and a rise in nativism.[180]

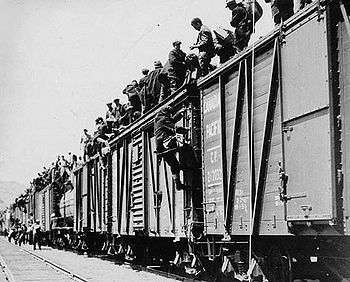

Times were especially hard in western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939. One response was the creation of new political parties such as the Social Credit movement and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, as well as popular protest in the form of the On-to-Ottawa Trek.[181]

Second World War

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Nazi Germany on September 10, 1939, delaying it one week after Britain acted to symbolically demonstrate independence. The war restored Canada's economic health and its self-confidence, as it played a major role in the Atlantic and in Europe. During the war, Canada became more closely linked to the U.S. The Americans took virtual control of Yukon in order to build the Alaska Highway, and were a major presence in the British colony of Newfoundland with major airbases.[182]

Mackenzie King — and Canada — were largely ignored by Winston Churchill and the British government despite Canada's major role in supplying food, raw materials, munitions and money to the hard-pressed British economy, training airmen for the Commonwealth, guarding the western half of the North Atlantic Ocean against German U-boats, and providing combat troops for the invasions of Italy, France and Germany in 1943–45. The government successfully mobilized the economy for war, with impressive results in industrial and agricultural output. The depression ended, prosperity returned, and Canada's economy expanded significantly. On the political side, Mackenzie King rejected any notion of a government of national unity.[183] The Canadian federal election, 1940 was held as normally scheduled, producing another majority for the Liberals.

Building up the Royal Canadian Air Force was a high priority; it was kept separate from Britain's Royal Air Force. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Agreement, signed in December 1939, bound Canada, Britain, New Zealand, and Australia to a program that eventually trained half the airmen from those four nations in the Second World War.[184]

After the start of war with Japan in December 1941, the government, in cooperation with the U.S., began the Japanese-Canadian internment, which sent 22,000 British Columbia residents of Japanese descent to relocation camps far from the coast. The reason was intense public demand for removal and fears of espionage or sabotage.[185] The government ignored reports from the RCMP and Canadian military that most of the Japanese were law-abiding and not a threat.[186]

The Battle of the Atlantic began immediately, and from 1943 to 1945 was led by Leonard W. Murray, from Nova Scotia. German U-boats operated in Canadian and Newfoundland waters throughout the war, sinking many naval and merchant vessels, as Canada took charge of the defenses of the western Atlantic.[187] The Canadian army was involved in the failed defence of Hong Kong, the unsuccessful Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the highly successful invasion of France and the Netherlands in 1944–45.[188]

The Conscription Crisis of 1944 greatly affected unity between French and English-speaking Canadians, though was not as politically intrusive as that of the First World War.[189] Of a population of approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in the Second World War. Many thousands more served with the Canadian Merchant Navy.[190] In all, more than 45,000 died, and another 55,000 were wounded.[191][192]

Post-war Era 1945–1960

Prosperity returned to Canada during the Second World War and continued in the proceeding years, with the development of universal health care, old-age pensions, and veterans' pensions.[193][194] The financial crisis of the Great Depression had led the Dominion of Newfoundland to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a crown colony ruled by a British governor.[195] In 1948, the British government gave voters three Newfoundland Referendum choices: remaining a crown colony, returning to Dominion status (that is, independence), or joining Canada. Joining the United States was not made an option. After bitter debate Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[196]

The foreign policy of Canada during the Cold War was closely tied to that of the United States. Canada was a founding member of NATO (which Canada wanted to be a transatlantic economic and political union as well[197]). In 1950, Canada sent combat troops to Korea during the Korean War as part of the United Nations forces. The federal government's desire to assert its territorial claims in the Arctic during the Cold War manifested with the High Arctic relocation, in which Inuit were moved from Nunavik (the northern third of Quebec) to barren Cornwallis Island;[198] this project was later the subject of a long investigation by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[199]

In 1956, the United Nations responded to the Suez Crisis by convening a United Nations Emergency Force to supervise the withdrawal of invading forces. The peacekeeping force was initially conceptualized by Secretary of External Affairs and future Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson.[200] Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his work in establishing the peacekeeping operation.[200] Throughout the mid-1950s, Louis St. Laurent (12th Prime Minister of Canada) and his successor John Diefenbaker attempted to create a new, highly advanced jet fighter, the Avro Arrow.[201] The controversial aircraft was cancelled by Diefenbaker in 1959. Diefenbaker instead purchased the BOMARC missile defense system and American aircraft. In 1958 Canada established (with the United States) the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).[202]

1960–1981

In the 1960s, what became known as the Quiet Revolution took place in Quebec, overthrowing the old establishment which centred on the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Quebec and led to modernizing of the economy and society.[203] Québécois nationalists demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis. John Saywell says, "The two kidnappings and the murder of Pierre Laporte were the biggest domestic news stories in Canada's history"[204][205] In 1976 the Parti Québécois was elected to power in Quebec, with a nationalist vision that included securing French linguistic rights in the province and the pursuit of some form of sovereignty for Quebec. This culminated in the 1980 referendum in Quebec on the question of sovereignty-association, which was turned down by 59% of the voters.[205]

In 1965, Canada adopted the maple leaf flag, although not without considerable debate and misgivings among large number of English Canadians.[206] The World's Fair titled Expo 67 came to Montreal, coinciding with the Canadian Centennial that year. The fair opened April 28, 1967, with the theme "Man and his World" and became the best attended of all BIE-sanctioned world expositions until that time.[207]

Legislative restrictions on Canadian immigration that had favoured British and other European immigrants were amended in the 1960s, opening the doors to immigrants from all parts of the world.[208] While the 1950s had seen high levels of immigration from Britain, Ireland, Italy, and northern continental Europe, by the 1970s immigrants increasingly came from India, China, Vietnam, Jamaica and Haiti.[209] Immigrants of all backgrounds tended to settle in the major urban centres, particularly Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.[209]

During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social and cultural change his political goals, including the pursuit of official bilingualism in Canada and plans for significant constitutional change.[210] The west, particularly the petroleum-producing provinces like Alberta, opposed many of the policies emanating from central Canada, with the National Energy Program creating considerable antagonism and growing western alienation.[211] Multiculturalism in Canada was adopted as the official policy of the Canadian government during the prime ministership of Pierre Trudeau.[212]

1982–1992

In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British parliament and granted Royal Assent by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29, while the Constitution Act was passed by the Canadian parliament and granted Royal Assent by the Queen on April 17, thus patriating the Constitution of Canada.[213] Previously, the constitution has existed only as an act passed of the British parliament, and was not even physically located in Canada, though it could not be altered without Canadian consent.[214] At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added in place of the previous Bill of Rights.[215] The patriation of the constitution was Trudeau's last major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

On June 23, 1985, Air India Flight 182 was destroyed above the Atlantic Ocean by a bomb on board exploding; all 329 on board were killed, of whom 280 were Canadian citizens.[216] The Air India attack is the largest mass murder in Canadian history.[217]

The Progressive Conservative (PC) government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to gain Quebec's support for the Constitution Act 1982 and end western alienation. In 1987 the Meech Lake Accord talks began between the provincial and federal governments, seeking constitutional changes favourable to Quebec.[218] The failure of the Meech Lake Accord resulted in the formation of a separatist party, Bloc Québécois.[219] The constitutional reform process under Prime Minister Mulroney culminated in the failure of the Charlottetown Accord which would have recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" but was rejected in 1992 by a narrow margin.[220]

Under Brian Mulroney, relations with the United States began to grow more closely integrated. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the "Acid Rain Treaty" to reduce acid rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the United States despite significant animosity from the Canadian public who were concerned about the economic and cultural impacts of close integration with the United States.[221] On July 11, 1990, the Oka Crisis land dispute began between the Mohawk people of Kanesatake and the adjoining town of Oka, Quebec.[222] The dispute was the first of a number of well-publicized conflicts between First Nations and the Canadian government in the late 20th century. In August 1990, Canada was one of the first nations to condemn Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and it quickly agreed to join the U.S.-led coalition. Canada deployed destroyers and later a CF-18 Hornet squadron with support personnel, as well as a field hospital to deal with casualties.[223]

Recent history: 1992–present

Following Mulroney's resignation as prime minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took office and became Canada's first female prime minister.[224] Campbell remained in office for only a few months: the 1993 election saw the collapse of the Progressive Conservative Party from government to two seats, while the Quebec-based sovereigntist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition.[225] Prime Minister Jean Chrétien of the Liberals took office in November 1993 with a majority government and was re-elected with further majorities during the 1997 and 2000 elections.[226]

In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty that was rejected by a margin of 50.6% to 49.4%.[227] In 1998, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province to be unconstitutional, and Parliament passed the Clarity Act outlining the terms of a negotiated departure.[227] Environmental issues increased in importance in Canada during this period, resulting in the signing of the Kyoto Accord on climate change by Canada's Liberal government in 2002. The accord was in 2007 nullified by Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative government, which proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change.[228]

Canada became the fourth country in the world and the first country in the Americas to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide with the enactment of the Civil Marriage Act.[229] Court decisions, starting in 2003, had already legalized same-sex marriage in eight out of ten provinces and one of three territories. Before the passage of the Act, more than 3,000 same-sex couples had married in these areas.[230]

The Canadian Alliance and PC Party merged into the Conservative Party of Canada in 2003, ending a 13-year division of the conservative vote. The party was elected twice as a minority government under the leadership of Stephen Harper in the 2006 federal election and 2008 federal election.[226] Harper's Conservative Party won a majority in the 2011 federal election with the New Democratic Party forming the Official Opposition for the first time.[231]

Under Harper, Canada and the United States continued to integrate state and provincial agencies to strengthen security along the Canada–United States border through the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative.[232] From 2002 to 2011, Canada was involved in the Afghanistan War as part of the U.S. stabilization force and the NATO-commanded International Security Assistance Force. In July 2010, the largest purchase in Canadian military history, totalling C$9 billion for the acquisition of 65 F-35 fighters, was announced by the federal government.[233] Canada is one of several nations that assisted in the development of the F-35 and has invested over C$168 million in the program.[234]

On October 19, 2015, Stephen Harper's Conservatives were defeated by a newly resurgent Liberal party under the leadership of Justin Trudeau and which had been reduced to third party status in the 2011 elections.[235]

Multiculturalism (cultural and ethnic diversity) has been emphasized in recent decades. Ambrose and Mudde conclude that: "Canada's unique multiculturalism policy ... which is based on a combination of selective immigration, comprehensive integration, and strong state repression of dissent on these policies. This unique blend of policies has led to a relatively low level of opposition to multiculturalism".[236][237]

Historiography

The Conquest of New France has always been a central and contested theme of Canadian memory. Cornelius Jaenen argues:

- The Conquest has remained a difficult subject for French-Canadian historians because it can be viewed either as economically and ideologically disastrous or as a providential intervention to enable Canadians to maintain their language and religion under British rule. For virtually all Anglophone historians it was a victory for British military, political, and economic superiority which would eventually only benefit the conquered.[238]

Historians of the 1950s tried to explain the economic inferiority of the French-Canadians by arguing that the Conquest:

destroyed an integral society and decapitated the commercial class; leadership of the conquered people fell to the Church; and, because commercial activity came to be monopolized by British merchants, national survival concentrated on agriculture.[239]

At the other pole, are those Francophone historians who see the positive benefit of enabling the preservation of language, and religion and traditional customs under British rule. French Canadian debates have escalated since the 1960s, as the Conquest is seen as a pivotal moment in the history of Québec's nationalism. Historian Jocelyn Létourneau suggested in the 21st century, "1759 does not belong primarily to a past that we might wish to study and understand, but, rather, to a present and a future that we might wish to shape and control."[240]

Anglophone historians, on the other hand, portray the Conquest as a victory for British military, political and economic superiority that was a permanent benefit to the French.[241]

Allan Greer argues that Whig history was once the dominant style of scholars. He says the:

- interpretive schemes that dominated Canadian historical writing through the middle decades of the twentieth century were built on the assumption that history had a discernible direction and flow. Canada was moving towards a goal in the nineteenth century; whether this endpoint was the construction of a transcontinental, commercial, and political union, the development of parliamentary government, or the preservation and resurrection of French Canada, it was certainly a Good Thing. Thus the rebels of 1837 were quite literally on the wrong track. They lost because they had to lose; they were not simply overwhelmed by superior force, they were justly chastised by the God of History.[242]

See also

- Canada's Story

- Events of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Heritage Minutes

- History of Canadian women

- History of Canadian sports

- History of Education in Canada

- History of Montreal

- History of North America

- History of Ottawa

- History of Quebec City

- History of Toronto

- History of Vancouver

- History of Winnipeg

- History Trek, Canadian History web portal designed for children

- National Historic Sites of Canada

- Persons of National Historic Significance

References

- ↑ Lawrence, David M. (2011). Andrea Ph.D., Alfred J., ed. Beringia and the Peopling of the New World. World History Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-85109-930-6.

- ↑ Goebel, Ted; Waters, Michael R.; O'Rourke, Dennis H. (2008). "The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas" (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–502. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1497G. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. PMID 18339930. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ↑ Wynn, Graeme (2007). Canada And Arctic North America: An Environmental History. ABC-CLIO. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-85109-437-0.

Laurel Sefton MacDowell (2012). An Environmental History of Canada. UBC Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7748-2104-9.

Guy Gugliotta (February 2013). "When Did Humans Come to the Americas?". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 25, 2015. - ↑ Fedje, Daryl W.; et al. (2004). Madsen, David B., ed. Late Wisconsin Environments and Archaeological Visibility on the Northern Northwest Coast. Entering America: Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum. University of Utah Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-87480-786-8.

- ↑ "Introduction". Unearthing the Law: Archaeological Legislation on Lands in Canada. Parks Canada. April 15, 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago as at U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ↑ Dixon, E. James (2007). Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M., eds. Archaeology and the First Americans. Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- ↑ Herz, Norman; Garrison, Ervan G. (1998). Geological Methods for Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-802511-5.

- ↑ Mange, Martin P.R. (1996). Carlson, Roy L.; Dalla Bona, Luke Robert, eds. Comparative Analysis of Microblade Cores from Haida Gwaii. Early Human Occupation in British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-7748-0535-3.

- ↑ Bryant, Vaugh M. Jr (1998). Gibbon, Guy; et al., eds. Pre-Clovis. Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: an Encyclopedia. Garland. p. 682. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

- ↑ Imbrie, John; Imbrie, Katherina Palmer (1979). Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44075-7.

- 1 2 Fiedel, Stuart J. (1992). Prehistory of the Americas. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-42544-5.

- ↑ "C. Prehistoric Periods (Eras of Adaptation)". The University of Calgary (The Applied History Research Group). 2000. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian M. (1992). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-321-01457-X.

- ↑ Lockard, Craig A. (2010). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Volume I: to 1500 (second ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-4390-8535-6.

- ↑ Hamilton, Michelle (2010). Collections and Objections: Aboriginal Material Culture in Southern Ontario. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7735-3754-5.

- ↑ Francis, R. Douglas; Jones, Richard; Smith, Donald B. (2009). Journeys: A History of Canada (second ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-17-644244-6.

- ↑ Brandon, William (2012). The Rise and Fall of North American Indians: From Prehistory through Geronimo. Roberts Rinehart. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-57098-453-2.

- ↑ Marshall, Ingeborg (1996). History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-7735-6589-0.

- ↑ "Maliseet and Mi'kmaq Languages". Aboriginal Affairs. Government of New Brunswick. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2007). Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M., eds. Pre-Contact Indian History. Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- ↑ "Background 1: Ojibwa history". Anishinaabe Arcs. Department of Science and Technology Studies · The Center for Cultural Design. 2003. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ↑ Ramsden, Peter G. (August 28, 2015). "Haudenosaunee (Iroquois)". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce E. (1995). "Dating the Iroquois Confederacy". Akwesasne Notes New Series. 1 (3): 62–63. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce Elliot; Mann, Barbara Alice, eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Greenwood. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-313-30880-2.

- ↑ Opie, John (2004). Rees, Amanda, ed. Ecology and Environment. The Great Plains Region. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Regional Cultures. Volume 4. Greenwood. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-313-32733-9.

- 1 2 Bengtson, John D. (2008). "Materials for a Comparative Grammar of the Dene-Caucasian (Sino-Caucasian) Languages" (PDF). Aspects of Comparative Linguistics. Moscow: RSUH. 3: 45–118. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "First Nations – People of the Northwest Coast". B.C. Archives. 1999. Archived from the original on March 14, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ↑ Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tyron, Darrell T., eds. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Maps. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 1065. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- ↑ Whitty, Julia (2010). Deep Blue Home: An Intimate Ecology of Our Wild Ocean. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-547-48707-6.

- ↑ "Tirigusuusiit, Piqujait and Maligait: Inuit Perspectives on Traditional Law". Nunavut Arctic College. 1999. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- 1 2 Wallace, Birgitta (2009). McManamon, Francis P.; Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; Milner, George R., eds. L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site. Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-33184-8.

- ↑ Axel Kristinsson (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. p. 216. ISBN 978-9979-9922-1-9.

- ↑ Leacock, Stephen (2014) [1915]. The Dawn of Canadian History: A Chronicle of Aboriginal Canada: The First European Visitors. The Floating Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-77652-909-4.

- ↑ Mills, William James (2003). Cabot, John (1450-ca. 1498). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia. Volume1, A-L. ABC-CLIO. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-57607-422-0.

- ↑ Wilson, Ian (1996). John Cabot and the Matthew. Breakwater Books. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-55081-131-5.

- ↑ Grimbly, Shona, ed. (2013) [2001]. The Northwest Passage. Atlas of Exploration. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-135-97006-2.

- ↑ Hiller, James; Higgins, Jenny (2013) [1997]. "John Cabot's voyage of 1498". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Diffie, Bailey Wallys (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire: 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-8166-0782-2.

- ↑ Rorabaugh, William J.; Critchlow, Donald T.; Baker, Paula C. (2004). America's Promise: A Concise History of the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7425-1189-7.

- ↑ Carlo Sauer (1975) [1971]. The Atlantic Coast (1520-1526). Sixteenth Century North America: The Land and the People as Seen by the Europeans. University of California Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-520-02777-0.

- ↑ Freeman-Grenville, Greville Stewart Parker (1975). Chronology of World History: a Calendar of Principal Events from 3000 BC to AD 1973 (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 387. ISBN 0-87471-765-5.

- ↑ Rompkey, Bill (2005). The Story of Labrador. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7735-7121-1.

- ↑ Hiller, J.K. (August 2004) [1998]. "The Portuguese Explorers". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Port-Royal National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada (Government of Canada). 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ↑ Litalien, Raymonde (2004). Champlain: The Birth of French America. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7735-7256-0.

- ↑ Loren, Diana Dipaolo (2008). In Contact: Bodies and Spaces in the Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-century Eastern Woodlands. Rowman Altamira. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7591-0661-1.

- ↑ Riendeau, Roger E. (2007) [2000]. A Brief History of Canada (second ed.). Infobase Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4381-0822-3.

- ↑ Margaret F. Pickett; Dwayne W. Pickett (2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521–1608. McFarland. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7864-6221-6.

- 1 2 Raymonde Litalien (2004). Champlain: The Birth of French America. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-7735-7256-0.

- ↑ Harold Adams Innis (1999). The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. University of Toronto Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8020-8196-4.

- ↑ J. M. Bumsted (2003). Canada's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-57607-672-9.

- ↑ James D. Kornwolf (2002). Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8018-5986-1.

- ↑ Margaret Conrad; Alvin Finkel (2005). History of the Canadian Peoples. Longman Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-321-27008-5.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul R (2002). Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a short introduction. University of Toronto Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8020-8469-9.

- ↑ Frederick Webb Hodge (2003). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Digital Scanning Inc. p. 585. ISBN 978-1-58218-749-5.

- ↑ Gilles Havard (2001). The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-native Diplomacy in the Seventeenth Century. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7735-6934-8.

- ↑ Quinn, David B. (1979) [1966]. "Gilbert, Sir Humphrey". In Brown, George Williams. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier : spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 978-1-58465-427-8.

- 1 2 Fry, Michael (2001). The Scottish Empire. Tuckwell Press. p. 21. ISBN 1-84158-259-X.

- ↑ "Charles Fort National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ↑ William Kingsford (1888). The History of Canada. K. Paul, French, Trübner & Company. p. 109.

- ↑ John Powell (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Infobase Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4381-1012-7.

- ↑ Robert V. Hine; John Mack Faragher (2007). Frontiers: A Short History of the American West. Yale University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-300-11710-3.

- ↑ The Canadian Frontier 1534–1760 by W.J. Eccles University of Toronto Published by University of New Mexico Press ISBN 0-8263-0705-1, 1969, revised 1983

- ↑ Shenwen, Li (2001). Stratégies missionnaires des Jésuites Français en Nouvelle-France et en Chine au XVIIieme siècle. Les Presses de l'Université Laval, L'Harmattan. p. 44. ISBN 2-7475-1123-5.

- ↑ Miquelon, Dale (December 16, 2013). "Ville-Marie (Colony)". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ↑ Louis Hartz (1969). The Founding of New Societies: Studies in the History of the United States, Latin America, South Africa, Canada, and Australia. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 224. ISBN 0-547-97109-5.

- 1 2 David L. Preston (2009). The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. U of Nebraska Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7.

- ↑ Thomas F. McIlwraith; Edward K. Muller (2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4616-3960-2.

- 1 2 3 Landry, Yves (Winter 1993). "Fertility in France and New France: The Distinguishing Characteristics of Canadian Behavior in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries". Social Science History. Université de Montréal. 17 (4): 586. JSTOR 1171305.

- ↑ "(Census of 1665–1666) Role-playing Jean Talon". Statistics Canada. 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Statistics for the 1666 Census". Library and Archives Canada. 2006. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Estimated population of Canada, 1605 to present". Statistics Canada. 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ John Powell (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Infobase Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4381-1012-7.

- ↑ Ronald J. Dale (2004). The Fall of New France: How the French Lost a North American Empire 1754–1763. James Lorimer & Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-55028-840-7.

- ↑ John E. Findling; Frank W. Thackeray (2011). What Happened?: An Encyclopedia of Events that Changed America Forever. ABC-CLIO. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-59884-621-8.

- ↑ Adam Hart-Davis (2012). History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. DK Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-7566-9858-4.

- ↑ Andrew Neil Porter (1994). Atlas of British overseas expansion. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-415-06347-0.

- ↑ Marsh, James (December 16, 2013). "Pierre de Troyes". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Our History: People: Explorers: Samuel Hearne". Hudson's Bay Company. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ John Grenier (2008). The Far Reaches Of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.

- ↑ Mark Zuehlke; C. Stuart Daniel (2006). Canadian Military Atlas: Four Centuries of Conflict from New France to Kosovo. Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-55365-209-0.

- ↑ John G. Reid (2004). The "Conquest" of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions. University of Toronto Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-8020-8538-2.

- ↑ Alan Axelrod (2007). Blooding at Great Meadows: young George Washington and the battle that shaped the man. Running Press. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-7624-2769-7.

- ↑ Ronald J. Dale (2004). The Fall of New France: How the French Lost a North American Empire 1754–1763. James Lorimer & Company. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-55028-840-7.

- ↑ Benjamin Irvin (2002). Samuel Adams: Son of Liberty, Father of Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-513225-0.

- ↑ Raddall, Thomas H (1971). Halifax, Warden of the North. McClelland and Stewart Limited. pp. 18–21. ISBN 1-55109-060-0. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ↑ John Grenier (2008). The far reaches of empire: war in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.

- ↑ Dean W. Jobb (2008). The Acadians: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph. Wiley. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-470-15772-5.

- ↑ Jacques Lacoursière (1996). Histoire populaire du Québec: De 1841 à 1896. III. Les éditions du Septentrion. p. 270. ISBN 978-2-89448-066-3.