History of the compass

The history of the compass extends back for more than 2000 years. The first compasses were made of lodestone, a naturally magnetized ore of iron, in Han dynasty China between 300 and 200 BC.[1] The compass was later used for navigation by the Song Dynasty.[2] Later compasses were made of iron needles, magnetized by striking them with a lodestone. Dry compasses begin appearing around 1300 in Medieval Europe.[3] This was supplanted in the early 20th century by the liquid-filled magnetic compass.[4]

Navigation prior to the compass

Prior to the introduction of the compass, geographical position and direction at sea were primarily determined by the sighting of landmarks, supplemented with the observation of the position of celestial bodies. On cloudy days, the Vikings may have used cordierite or some other birefringent crystal to determine the sun's direction and elevation from the polarization of daylight; their astronomical knowledge was sufficient to let them use this information to determine their proper heading.[5] The invention of the compass enabled the determination of heading when the sky was overcast or foggy, and when landmarks were not in sight. This enabled mariners to navigate safely far from land, increasing sea trade, and contributing to the Age of Discovery.[6][7]

Geomancy and feng shui

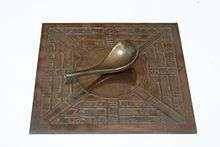

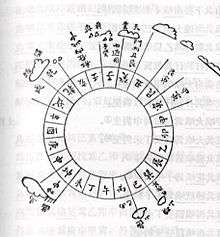

The compass was invented in China during the Han Dynasty between the 2nd century BC and 1st century AD, where it was called the "south-governor" (sīnán 司南).[2] The magnetic compass was not, at first, used for navigation, but for geomancy and fortune-telling by the Chinese. The earliest Chinese magnetic compasses were possibly used to order and harmonize buildings in accordance with the geomantic principles of feng shui. These early compasses were made with lodestone, a form of the mineral magnetite that is a naturally occurring magnet and aligns itself with the Earth’s magnetic field. People in ancient China discovered that if a lodestone was suspended so it could turn freely, it would always point toward the magnetic poles. Early compasses were used to choose areas suitable for building houses and to search for rare gems. Compasses were later adapted for navigation during the Song Dynasty in the 11th century.[1]

Based on Krotser and Coe's discovery of an Olmec hematite artifact in Mesoamerica, radiocarbon dated to 1400–1000 BC, astronomer John Carlson has hypothesized that the Olmec might have used the geomagnetic lodestone earlier than 1000 BC for geomancy, a method of divination, which if proven true, predates the Chinese use of magnetism for feng shui by a millennium.[8] Carlson speculates that the Olmecs used similar artifacts as a directional device for astronomical or geomantic purposes but does not suggest navigational usage. The artifact is part of a polished hematite bar with a groove at one end, possibly used for sighting. Carlson's claims have been disputed by other scientific researchers, who have suggested that the artifact is actually a constituent piece of a decorative ornament and not a purposely built compass.[9] Several other hematite or magnetite artifacts have been found at pre-Columbian archaeological sites in Mexico and Guatemala.[10][11]

Early navigational compass

A number of early cultures used lodestones, suspended so they could turn, as magnetic compasses for navigation. Early mechanical compasses are referenced in written records of the Chinese, who began using it for navigation sometime between the 9th and 11th century, "some time before 1050, possibly as early as 850."[12] A common theory by historians[13][14] suggests that the Arabs introduced the compass from China to Europe, although current textual evidence only supports the fact that Chinese use of the navigational compass preceded that of Europe and the Middle East.[15] Some scholars suggested the compass was transmitted from China to Europe and Arabs via Indian Ocean.[16] However, some scholars proposed an independent European invention.[17]

China

There is disagreement as to exactly when the compass was invented. These are noteworthy Chinese literary references in evidence for its antiquity:

- The magnetic compass was first invented as a device for divination as early as the Chinese Han Dynasty (since about 206 BC).[1][2][19] The compass was used in Song Dynasty China by the military for navigational orienteering by 1040–44,[15][20][21] and was used for maritime navigation by 1111 to 1117.[22]

- The earliest Chinese literature reference to magnetism lies in the 4th century BC writings of Wang Xu (鬼谷子): "The lodestone attracts iron."[23] The book also notes that the people of the state of Zheng always knew their position by means of a "south-pointer"; some authors suggest that this refers to early use of the compass.[1][24]

- The first mention of a spoon, speculated to be a lodestone, observed pointing in a cardinal direction is a Chinese work composed between 70 and 80 AD (Lunheng), which records that "But when the south pointing spoon is thrown upon the ground, it comes to rest pointing at the south."[25] Within the text, the author Wang Chong describes the spoon as a phenomenon that he has personally observed.[26] Although the passage does not explicitly mention magnetism,[27] according to Chen-Cheng Yih, the "device described by Wang Chong has been widely considered to be the earliest form of the magnetic compass."[18]

- The first clear account of magnetic declination occurs in the Kuan Shih Ti Li Chih Meng ("Mr. Kuan's Geomantic Instructor"), dating to 880.[28] Another text, the Chiu Thien Hsuan Nu Chhing Nang Hai Chio Ching ("Blue Bag Sea Angle Manual") from around the same period, also has an implicit description of magnetic declination. It has been argued that this knowledge of declination requires the use of the compass.[28]

- A reference to a magnetized needle as a "mysterious needle" appears in 923–926 in the Chung Hua Ku Chin Chu text written by Ma Kao. The same passage is also attributed to the 4th-century AD writer Tshui Pao, although it is postulated that the former text is more authentic. The shape of the needle is compared to that of a tadpole, and may indicate the transition between "lodestone spoons" and "iron needles."[29]

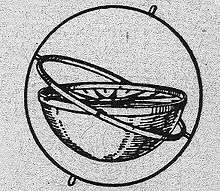

- The earliest reference to a specific magnetic direction finder device for land navigation is recorded in a Song Dynasty book dated to 1040–44. There is a description of an iron "south-pointing fish" floating in a bowl of water, aligning itself to the south. The device is recommended as a means of orientation "in the obscurity of the night." The Wujing Zongyao (武經總要, "Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques") stated: "When troops encountered gloomy weather or dark nights, and the directions of space could not be distinguished...they made use of the [mechanical] south-pointing carriage, or the south-pointing fish."[20] This was achieved by heating of metal (especially if steel), known today as thermoremanence, and would have been capable of producing a weak state of magnetization.[20] While the Chinese achieved magnetic remanence and induction by this time, in both Europe and Asia the phenomenon was attributed to the supernatural and occult, until about 1600 when William Gilbert published his De Magnete.[30]

- The first incontestable reference to a magnetized needle in Chinese literature appears in 1088.[21] The Dream Pool Essays, written by the Song Dynasty polymath scientist Shen Kuo, contained a detailed description of how geomancers magnetized a needle by rubbing its tip with lodestone, and hung the magnetic needle with one single strain of silk with a bit of wax attached to the center of the needle. Shen Kuo pointed out that a needle prepared this way sometimes pointed south, sometimes north.

- The earliest explicit recorded use of a magnetic compass for maritime navigation is found in Zhu Yu's book Pingchow Table Talks (萍洲可談; Pingzhou Ketan) and dates from 1111 to 1117: The ship's pilots are acquainted with the configuration of the coasts; at night they steer by the stars , and in the daytime by the sun. In dark weather they look at the south pointing needle.[22]

Thus, the use of a magnetic compass by the military for land navigation occurred sometime before 1044, but incontestable evidence for the use of the compass as a maritime navigational device did not appear until 1117.

The typical Chinese navigational compass was in the form of a magnetic needle floating in a bowl of water.[31] According to Needham, the Chinese in the Song Dynasty and continuing Yuan Dynasty did make use of a dry compass, although this type never became as widely used in China as the wet compass.[32] Evidence of this is found in the Shilin guangji ("Guide Through the Forest of Affairs"), published in 1325 by Chen Yuanjing, although its compilation had taken place between 1100 and 1250.[32] The dry compass in China was a dry suspension compass, a wooden frame crafted in the shape of a turtle hung upside down by a board, with the lodestone sealed in by wax, and if rotated, the needle at the tail would always point in the northern cardinal direction.[32] Although the European compass-card in box frame and dry pivot needle was adopted in China after its use was taken by Japanese pirates in the 16th century (who had in turn learned of it from Europeans),[33] the Chinese design of the suspended dry compass persisted in use well into the 18th century.[34] However, according to Kreutz there is only a single Chinese reference to a dry-mounted needle (built into a pivoted wooden tortoise) which is dated to between 1150 and 1250, and claims that there is no clear indication that Chinese mariners ever used anything but the floating needle in a bowl until the 16th century.[31]

The first recorded use of a 48 position mariner's compass on sea navigation was noted in The Customs of Cambodia by Yuan Dynasty diplomat Zhou Daguan, he described his 1296 voyage from Wenzhou to Angkor Thom in detail; when his ship set sail from Wenzhou, the mariner took a needle direction of “ding wei” position, which is equivalent to 22.5 degree SW. After they arrived at Baria, the mariner took "Kun Shen needle", or 52.5 degree SW.[35] Zheng He's Navigation Map, also known as the "Mao Kun Map", contains a large amount of detail "needle records" of Zheng He's expeditions.[36]

At present, according to Kreutz, scholarly consensus is that the Chinese invention used in navigation pre-dates the first European mention of a compass by 150 years.[15] However, there are questions over diffusion. The first recorded appearance of the use of the compass in Europe (1190)[37] is earlier than in the Muslim world (1232),[38][39] as a description of a magnetized needle and its use among sailors occurs in Alexander Neckam's De naturis rerum (On the Natures of Things), written in 1190.[37][40] The earliest reference to a compass in the Middle East is attributed to the Persians, who describe an iron fish-like compass in a talebook dating from 1232.[38] In the Arab world, the earliest reference comes in The Book of the Merchants' Treasure, written by one Baylak al-Kibjaki in Cairo about 1282.[39] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance accordingly. The common shape of the early compass as a magnetized needle floating in a bowl of water is considered as an evidence of diffusion from China to Europe.[37] Another evidence supported diffusion theory is the temporal proximity of the Chinese beginning to use compass (after its first use in divination) in navigation to the first appearance of compass in Europe and Arab.[37] The Persian compass is described as fish-like, which is a characteristic of early Chinese compasses from the 11th century, suggesting transmission from China to Persia.[41] The view of some academics that compass was transmitted to Europe from China, through the Islamic world.[13][14] Some suggested the compass was transmitted to Europe and Arab through Indian Ocean from China.[16] Other scholars suggested compass was brought by crusades to Europe from China.[42] However, some scholars proposed an independent European invention of the compass:[43] The first record of a magnetic compass in Europe (1187 by Neckam) proceeded those by Arabs,[17] and the Arabic word for compass (al-kunbas) appears to be derived from Italian roots,[44] which indicates an independent European invention.

Medieval Europe

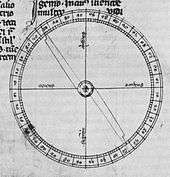

Alexander Neckam reported the use of a magnetic compass for the region of the English Channel in the texts De utensilibus and De naturis rerum,[46] written between 1187 and 1202, after he returned to England from France[47] and prior to entering the Augustinian abbey at Cirencester.[48] Robert Southey suggested that the Siete Partidas contained a reference from the 1250s to the needle being used for navigation.[49] In 1269 Petrus Peregrinus of Maricourt described a floating compass for astronomical purposes as well as a dry compass for seafaring, in his well-known Epistola de magnete.[46] In the Mediterranean, the introduction of the compass, at first only known as a magnetized pointer floating in a bowl of water,[50] went hand in hand with improvements in dead reckoning methods, and the development of Portolan charts, leading to more navigation during winter months in the second half of the 13th century.[51] While the practice from ancient times had been to curtail sea travel between October and April, due in part to the lack of dependable clear skies during the Mediterranean winter, the prolongation of the sailing season resulted in a gradual, but sustained increase in shipping movement; by around 1290 the sailing season could start in late January or February, and end in December.[52] The additional few months were of considerable economic importance. For instance, it enabled Venetian convoys to make two round trips a year to the Levant, instead of one.[53]

At the same time, traffic between the Mediterranean and northern Europe also increased, with first evidence of direct commercial voyages from the Mediterranean into the English Channel coming in the closing decades of the 13th century, and one factor may be that the compass made traversal of the Bay of Biscay safer and easier.[54] However, critics like Kreutz have suggested that it was later in 1410 that anyone really started steering by compass.[55]

Muslim world

The earliest reference to an iron fish-like compass in the Islamic world occurs in a Persian book from 1232.[38] This fish shape was from a typical early Chinese design.[41] The earliest Arabic reference to a compass, in the form of magnetic needle in a bowl of water, comes from the Yemeni Sultan and astronomer Al-Ashraf in 1282.[39] He also appears to be the first to make use of the compass for astronomical purposes.[56] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance in the Arab world accordingly.[38] In addition he reports that on the Indian Ocean floating compasses with a hollow floating fish made of sheet-iron were used.[17]

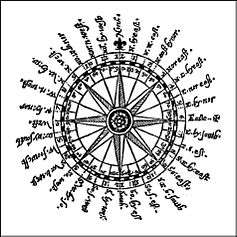

In 1300, another Arabic treatise written by the Egyptian astronomer and muezzin Ibn Simʿūn describes a dry compass for use as a "Qibla (Kabba) indicator" to find the direction to Mecca. Like Peregrinus' compass, however, Ibn Simʿūn's compass did not feature a compass card.[46] In the 14th century, the Syrian astronomer and timekeeper Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) invented a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass. He invented it for the purpose of finding the times of salat prayers.[57] Arab navigators also introduced the 32-point compass rose during this time.[58] In 1399, an Egyptian reports two different kinds of magnetic compass. One instrument is a “fish” made of willow wood or pumpkin, into which a magnetic needle is inserted and which afterwards is sealed with tar or wax to prevent the penetration of water. The other instrument is a dry compass.[17]

India

The development of the magnetic compass is highly uncertain. The compass is mentioned in fourth-century AD Tamil nautical books; moreover, its early name of macchayantra (fish machine) suggest a Chinese origin. In its Indian form, the wet compass often consisted of a fish-shaped magnet, float in a bowl filled with oil.[59][60] This fish shape was from a typical early Chinese design.[41]

Medieval Africa

There is evidence that the distribution of the compass from China likely also reached eastern Africa by way of trade through the end of the Silk Road that ended in East African centre of trade in Somalia and the Swahili city-state kingdoms.[61] There is evidence that Swahili maritime merchants and sailors acquired the compass at some point and used it for navigation.[62]

Dry compass

The dry mariner's compass was invented in Europe around 1300. The dry mariner's compass consists of three elements: A freely pivoting needle on a pin enclosed in a little box with a glass cover and a wind rose, whereby "the wind rose or compass card is attached to a magnetized needle in such a manner that when placed on a pivot in a box fastened in line with the keel of the ship the card would turn as the ship changed direction, indicating always what course the ship was on".[3] Later, compasses were often fitted into a gimbal mounting to reduce grounding of the needle or card when used on the pitching and rolling deck of a ship.

While pivoting needles in glass boxes had already been described by the French scholar Peter Peregrinus in 1269,[63] and by the Egyptian scholar Ibn Simʿūn in 1300,[46] traditionally Flavio Gioja (fl. 1302), an Italian pilot from Amalfi, has been credited with perfecting the sailor's compass by suspending its needle over a compass card, thus giving the compass its familiar appearance.[64] Such a compass with the needle attached to a rotating card is also described in a commentary on Dante's Divine Comedy from 1380, while an earlier source refers to a portable compass in a box (1318),[65] supporting the notion that the dry compass was known in Europe by then.[31]

Bearing compass

A bearing compass is a magnetic compass mounted in such a way that it allows the taking of bearings of objects by aligning them with the lubber line of the bearing compass.[66] A surveyor's compass is a specialized compass made to accurately measure heading of landmarks and measure horizontal angles to help with map making. These were already in common use by the early 18th century and are described in the 1728 Cyclopaedia. The bearing compass was steadily reduced in size and weight to increase portability, resulting in a model that could be carried and operated in one hand. In 1885, a patent was granted for a hand compass fitted with a viewing prism and lens that enabled the user to accurately sight the heading of geographical landmarks, thus creating the prismatic compass.[67] Another sighting method was by means of a reflective mirror. First patented in 1902, the Bézard compass consisted of a field compass with a mirror mounted above it.[68][69] This arrangement enabled the user to align the compass with an objective while simultaneously viewing its bearing in the mirror.[68][70]

In 1928, Gunnar Tillander, a Swedish unemployed instrument maker and avid participant in the sport of orienteering, invented a new style of bearing compass. Dissatisfied with existing field compasses, which required a separate protractor in order to take bearings from a map, Tillander decided to incorporate both instruments into a single instrument. It combined a compass with a protractor built into the base. His design featured a metal compass capsule containing a magnetic needle with orienting marks mounted into a transparent protractor baseplate with a lubber line (later called a direction of travel indicator). By rotating the capsule to align the needle with the orienting marks, the course bearing could be read at the lubber line. Moreover, by aligning the baseplate with a course drawn on a map – ignoring the needle – the compass could also function as a protractor. Tillander took his design to fellow orienteers Björn, Alvid, and Alvar Kjellström, who were selling basic compasses, and the four men modified Tillander's design.[71] In December 1932, the Silva Company was formed with Tillander and the three Kjellström brothers, and the company began manufacturing and selling its Silva orienteering compass to Swedish orienteers, outdoorsmen, and army officers.[71][72][73][74]

Liquid compass

The liquid compass is a design in which the magnetized needle or card is damped by fluid to protect against excessive swing or wobble, improving readability while reducing wear. A rudimentary working model of a liquid compass was introduced by Sir Edmund Halley at a meeting of the Royal Society in 1690.[75] However, as early liquid compasses were fairly cumbersome and heavy, and subject to damage, their main advantage was aboard ship. Protected in a binnacle and normally gimbal-mounted, the liquid inside the compass housing effectively damped shock and vibration, while eliminating excessive swing and grounding of the card caused by the pitch and roll of the vessel. The first liquid mariner's compass believed practicable for limited use was patented by the Englishman Francis Crow in 1813.[76][77] Liquid-damped marine compasses for ships and small boats were occasionally used by the Royal Navy from the 1830s through 1860, but the standard Admiralty compass remained a dry-mount type.[78] In the latter year, the American physicist and inventor Edward Samuel Ritchie patented a greatly improved liquid marine compass that was adopted in revised form for general use by the United States Navy, and later purchased by the Royal Navy as well.[79]

Despite these advances, the liquid compass was not introduced generally into the Royal Navy until 1908. An early version developed by RN Captain Creak proved to be operational under heavy gunfire and seas, but was felt to lack navigational precision compared with the design by Lord Kelvin.[4][80] However, with ship and gun sizes continuously increasing, the advantages of the liquid compass over the Kelvin compass became unavoidably apparent to the Admiralty, and after widespread adoption by other navies, the liquid compass was generally adopted by the Royal Navy.[4]

Liquid compasses were next adapted for aircraft. In 1909, Captain F.O. Creagh-Osborne, Superintendent of Compasses at the Admiralty, introduced his Creagh-Osborne aircraft compass, which used a mixture of alcohol and distilled water to damp the compass card.[81][82] After the success of this invention, Capt. Creagh-Osborne adapted his design to a much smaller pocket model[83] for individual use[84] by officers of artillery or infantry, receiving a patent in 1915.[85]

In December 1932, the newly founded Silva Company of Sweden introduced its first baseplate or bearing compass that used a liquid-filled capsule to damp the swing of the magnetized needle.[71] The liquid-damped Silva took only four seconds for its needle to settle in comparison to thirty seconds for the original version.[71]

In 1933 Tuomas Vohlonen, a surveyor by profession, applied for a patent for a unique method of filling and sealing a lightweight celluloid compass housing or capsule with a petroleum distillate to dampen the needle and protect it from shock and wear caused by excessive motion.[86] Introduced in a wrist-mount model in 1936 as the Suunto Oy Model M-311, the new capsule design led directly to the lightweight liquid-filled field compasses of today.[86]

Non-navigational uses

Astronomy

Three astronomical compasses meant for establishing the meridian were described by Peter Peregrinus in 1269 (referring to experiments made before 1248)[87] In the 1300s, an Arabic treatise written by the Egyptian astronomer and muezzin Ibn Simʿūn describes a dry compass for use as a "Qibla indicator" to find the direction to Mecca. Ibn Simʿūn's compass, however, did not feature a compass card nor the familiar glass box.[46] In the 14th century, the Syrian astronomer and timekeeper Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) invented a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass. He invented it for the purpose of finding the times of salat prayers.[57] Arab navigators also introduced the 32-point compass rose during this time.[58]

Building orientation

Evidence for the orientation of buildings by the means of a magnetic compass can be found in 12th-century Denmark: one fourth of its 570 Romanesque churches are rotated by 5–15 degrees clockwise from true east-west, thus corresponding to the predominant magnetic declination of the time of their construction.[88] Most of these churches were built in the 12th century, indicating a fairly common usage of magnetic compasses in Europe by then.[89]

Mining

The use of a compass as a direction finder underground was pioneered in the Tuscan mining town Massa where floating magnetic needles were employed for tunnelling, and for defining the claims of the various mining companies, as early as the 13th century.[90] In the second half of the 15th century, the compass became standard equipment for Tyrolian miners. Shortly afterwards the first detailed treatise dealing with the underground use of compasses was published by a German miner Rülein von Calw (1463–1525).[91]

Sun compass

A sun compass uses the position of the Sun in the sky to determine the directions of the cardinal points, making allowance for the local latitude and longitude, time of day, equation of time, and so on. At fairly high latitudes, an analog-display watch can be used as a very approximate sun compass. A simple sundial can be used as a much better one. An automatic sun compass developed by Lt. Col. James Allason, a mechanised cavalry officer, was adopted by the British Army in India in 1938 for use in tanks and other armoured vehicles where the magnetic field was subject to distortion, affecting the standard issue prismatic compass. Cloudy skies prohibited its use in European theatres. A copy of the manual is preserved in the Imperial War Museum in London.[92]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Lowrie, William (2007). Fundamentals of Geophysics. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-521-67596-3.

Early in the Han Dynasty, between 300-200 BC, the Chinese fashioned a rudimentary compass out of lodestone... the compass may have been used in the search for gems and the selection of sites for houses... their directive power led to the use of compasses for navigation

- 1 2 3 Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W. (1983). The Earth's magnetic field: Its history, origin and planetary perspective (2nd printing ed.). San Francisco: Academic press. p. 1. ISBN 0-12-491242-7.

- 1 2 Lane, p. 615

- 1 2 3 W. H. Creak: "The History of the Liquid Compass", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 56, No. 3 (1920), pp. 238-239

- ↑ Gábor Horváth; et al. (2011). "On the trail of Vikings with polarized skylight". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 366 (1565): 772–782. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0194.

- ↑ Merson, John (1990). The Genius That Was China: East and West in the Making of the Modern World. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-87951-397-7.

- ↑ Bacon, Francis (1620). Novum Organum Scientiarum.

It is well to observe the force and virtue of consequences of discoveries, and there are to be seen nowhere more conspicuously than in those three which were unknown to the ancients, and of which the origins, although recent, are obscure and inglorious; namely printing, gunpowder, and the magnet. For these three have changed the whole state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation; whence have followed innumerable changes, insomuch that no empire, no secret, no star seems to have exerted greater power in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries... had done more to transform the modern world and mark it off from antiquity and the middle ages.

- ↑ John B. Carlson, "Lodestone Compass: Chinese or Olmec Primacy? Multidisciplinary Analysis of an Olmec Hematite Artifact from San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico", Science, New Series, Vol. 189, No. 4205 (5 September 1975), pp. 753-760 (1975)

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Lu Gwei-Djen (1985). Trans-Pacific Echoes and Resonances: Listening Once Again. World Scientific. p. 21.

- ↑ Guimarães, A. P. (2004). "Mexico and the early history of magnetism". Revista Mexicana de Fisica. 50: 51–53. Bibcode:2004RMxFE..50...51G.

- ↑ "Chapter 3". Dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1986). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-521-31560-9.

the introduction of the mariner's compass on Chinese ships some time before 1050, possibly as early as 850

- 1 2 Needham, Joseph. Cambridge University Press. University of California Press. p. 173.

Thus the possibility presents itself that... it may have formed part of one of those transmissions from Asia which we find in so many fields of applied science

- 1 2 McEachren, Justin W. General Science Quarterly, Volumes 5-6. University of California Press. p. 337.

From the Chinese, the Arabs in all probability learned to use the magnetic needle, and in this round-about fashion it was brought to Europe

- 1 2 3 Kreutz, p. 367

- 1 2 Bentley, Jerry. Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. p. 637.

- 1 2 3 4 "Early Arabic Sources on the Magnetic Compass" (PDF). Lancaster.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- 1 2 Selin, Helaine (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. p. 541. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

The device described by Wang Chong has been widely considered to be the earliest form of the magnetic compass

- ↑ Li Shu-hua, p. 176

- 1 2 3 Needham, p. 252

- 1 2 Li Shu-hua, p. 182f.

- 1 2 Colin A. Ronan; Joseph Needham (25 July 1986). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-521-31560-9.

- ↑

- ↑ Needham p. 190

- ↑ Needham p. 18

- ↑ Needham p. 18 "here the author is contrasting a fable which he did not believe with actual events he has seen with his own eyes"

- ↑ Li Shu-hua, p. 180

- 1 2 Needham, Joseph (1970). Clerks and Craftsmen in China and the West. Cambridge University Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-521-07235-9.

The geomantic book Kuan Shih Ti Li Chih Meng... has the first account of it... the Chiu Thien Hsuan Nu Chhing Nang Hai Chio Ching... includes an implicit reference to declination

- ↑ Needham p. 273-274

- ↑ Benjamin A. Elman (30 June 2009). On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550–1900. Harvard University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-674-03647-5.

- 1 2 3 Kreutz, p. 373

- 1 2 3 Needham p. 255

- ↑ Needham, p. 289.

- ↑ Needham, p. 290

- ↑ Zhou

- ↑ Ma, Appendix 2

- 1 2 3 4 Kreutz, p. 368

- 1 2 3 4 Kreutz, p. 370

- 1 2 3 Kreutz, p. 369

- ↑ Lanza, Roberto; Meloni, Antonio (2006). The earth's magnetism an introduction for geologists. Berlin: Springer. p. 255. ISBN 978-3-540-27979-2.

- 1 2 3 Needham p. 12-13 "...that the floating fish-shaped iron leaf spread outside China as a technique, we know from the description of Muhammad al' Awfi just two hundred years later"

- ↑

- ↑ "Principles of the Magnetic Methods in Geophysics", Alex A. Kaufman, Richard O. Hansen, Robert L. Kleinberg pg 149.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Helaine Seline, Springe-Science+Business Media, BV, pg 233

- ↑ Peregrinus, Peter (1269). Epistola de magnete. Books.google.co.uk.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schmidl, Petra G. (1996–97). "Two Early Arabic Sources On The Magnetic Compass". Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 1: 81–132. http://www.uib.no/jais/v001ht/01-081-132schmidl1.htm#_ftn4

- ↑ Neckam, Alexander (1863). Alexandri Neckam De Naturis Rerum Libri Duoi. Longman, Roberts, and Green. p. xi.

- ↑ Gutman, Oliver (2003). Liber Celi Et Mundi. BRILL. p. xx. ISBN 9789004132283.

probably whilst teaching theology at Oxford before entering the Augustinian abbey at Cirencester in 1202

- ↑ Southey, Robert (1812). Omniana. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. p. 210.

There is a passage in the Partidas respecting the needle, which was written half a century before its supposed invention at Amalfi

- ↑ Kreutz, p. 368–369

- ↑ Lane, p. 606f.

- ↑ Lane, p. 608

- ↑ Lane, p. 608 & 610

- ↑ Lane, p. 608 & 613

- ↑ Kreutz, p. 372–373

- ↑ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1988). "Gleanings from an Arabist's Workshop: Current Trends in the Study of Medieval Islamic Science and Medicine". Isis. 79 (2): 246–266 [263]. doi:10.1086/354701.

- 1 2 (King 1983, pp. 547–8)

- 1 2 Tibbetts, G. R. (1973). "Comparisons between Arab and Chinese Navigational Techniques". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 36 (1): 97–108 [105–6]. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00098013.

- ↑ Helaine Selin, ed. (2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ↑ The American Journal of Science. Books.google.com. 1919. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ Stockwell, Foster (2003). Westerners in China : a history of exploration and trade, ancient times through the present. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7864-1404-8.

- ↑ Bulliet, Richard W.; et al. The earth and its peoples : a global history (5th, Student ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-538-74438-6.

- ↑ Taylor

- ↑ Lane, p. 616

- ↑ Kreutz, p. 374

- ↑ "Hand Bearing Compass". West Coast Offshore Marine. 2009. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ↑ Frazer, Persifor, A Convenient Device to be Applied to the Hand Compass, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 22, No. 118 (Mar., 1885), p. 216

- 1 2 Jean-Patrick Donzey. "Bezard 1". Compass Museum. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ Barnes, Scott, Churchill, James, and Jacobson, Cliff, The Ultimate Guide to Wilderness Navigation, Globe Pequot Press (2002), ISBN 1-58574-490-5, ISBN 978-1-58574-490-9, p. 27

- ↑ Barnes, p. 27

- 1 2 3 4 Litsky, Frank, Bjorn Kjellstrom, 84, Orienteer and Inventor of Modern Compass, Obituaries, The New York Times, 1 September 1995

- ↑ Seidman, p. 68

- ↑ Kjellström, Björn, 19th Hole: The Readers Take Over: Orienteering, Sports Illustrated, 3 March 1969

- ↑ Silva Sweden AB, Silva Sweden AB and Silva Production AB Become One Company: History, Press Release 28 April 2000

- ↑ Gubbins, David, Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism, Springer Press (2007), ISBN 1-4020-3992-1, ISBN 978-1-4020-3992-8, p. 67

- ↑ Fanning, A.E., Steady As She Goes: A History of the Compass Department of the Admiralty, HMSO, Department of the Admiralty (1986), pp. 1-10

- ↑ Gubbins, p. 67

- ↑ Fanning, A.E., pp. 1-10

- ↑ Warner, Deborah, Compasses and Coils: The Instrument Business of Edward S. Ritchie, Rittenhouse, Vol. 9, No. 1 (1994), pp. 1-24

- ↑ Gubbins, p. 67: The use of parallel or multiple needles was by no means a new development; their use in dry-mount marine compasses was pioneered by navigation officers of the Dutch East India Company as early as 1649.

- ↑ Davis, Sophia, Raising The Aerocompass In Early Twentieth-century Britain, British Journal for the History of Science, published online by Cambridge University Press, 15 Jul 2008, pp. 1-22

- ↑ Colvin, Fred H., Aircraft Mechanics Handbook: A Collection of Facts and Suggestions from Factory and Flying Field to Assist in Caring for Modern Aircraft, McGraw-Hill Book Co. Inc. (1918), pp. 347-348

- ↑ The Compass Museum, Article: Though the Creagh-Osborne was offered in a wrist-mount model, it proved too bulky and heavy in this form.

- ↑ Hughes, Henry A., Improvements in prismatic compasses with special reference to the Creagh-Osborne patent compass, Transactions of The Optical Society 16, London: The Optical Society (1915), pp. 17-43: The first liquid-damped compass compact enough for pocket or pouch was the Creagh-Osborne, patented in 1915 in Great Britain.

- ↑ Hughes, Henry A., pp. 17-43

- 1 2

- ↑ Taylor, p. 1f.

- ↑ Abrahamsen, N. (1992). "Evidence for Church Orientation by Magnetic Compass in Twelfth-Century Denmark". Archaeometry. 34 (2): 293–303. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1992.tb00499.x. See page 293.

- ↑ Abrahamsen, N. (1992). "Evidence for Church Orientation by Magnetic Compass in Twelfth-Century Denmark". Archaeometry. 34 (2): 293–303. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1992.tb00499.x. See page 303.

- ↑ Ludwig and Schmidtchen, p. 62–64

- ↑ Ludwig and Schmidtchen, p. 64

- ↑ Ringside Seat, by James Allason, Timewell Press, London 2007

References

- Admiralty, Great Britain (1915) Admiralty manual of navigation, 1914, Chapter XXV: "The Magnetic Compass (continued): the analysis and correction of the deviation", London : HMSO, 525 p.

- Aczel, Amir D. (2001) The Riddle of the Compass: The Invention that Changed the World, 1st Ed., New York : Harcourt, ISBN 0-15-600753-3

- Carlson, John B (1975). "Multidisciplinary analysis of an Olmec hematite artifact from San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico". Science. 189 (4205): 753–760. Bibcode:1975Sci...189..753C. doi:10.1126/science.189.4205.753. PMID 17777565.

- Gies, Frances and Gies, Joseph (1994) Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Age, New York : HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-016590-1

- Gubbins, David, Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism, Springer Press (2007), ISBN 1-4020-3992-1, ISBN 978-1-4020-3992-8

- Gurney, Alan (2004) Compass: A Story of Exploration and Innovation, London : Norton, ISBN 0-393-32713-2

- Johnson, G. Mark, The Ultimate Desert Handbook, 1st Ed., Camden, Maine: McGraw-Hill (2003), ISBN 0-07-139303-X

- King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis. 74 (4): 531–555. doi:10.1086/353360.

- Kreutz, Barbara M. (1973) "Mediterranean Contributions to the Medieval Mariner's Compass", Technology and Culture, 14 (3: July), p. 367–383 JSTOR 3102323

- Lane, Frederic C. (1963) "The Economic Meaning of the Invention of the Compass", The American Historical Review, 68 (3: April), p. 605–617 JSTOR 1847032

- Li Shu-hua (1954) "Origine de la Boussole 11. Aimant et Boussole", Isis, 45 (2: July), p. 175–196

- Ludwig, Karl-Heinz and Schmidtchen, Volker (1997) Metalle und Macht: 1000 bis 1600, Propyläen Technikgeschichte, Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, ISBN 3-549-05633-8

- Ma, Huan (1997) Ying-yai sheng-lan [The overall survey of the ocean's shores (1433)], Feng, Ch'eng-chün (ed.) and Mills, J.V.G. (transl.), Bangkok : White Lotus Press, ISBN 974-8496-78-3

- Needham, Joseph (1986) Science and civilisation in China, Vol. 4: "Physics and physical technology", Pt. 1: "Physics", Taipei: Caves Books, originally publ. by Cambridge University Press (1962), ISBN 0-521-05802-3

- Needham, Joseph and Ronan, Colin A. (1986) The shorter Science and civilisation in China : an abridgement of Joseph Needham's original text, Vol. 3, Chapter 1: "Magnetism and Electricity", Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-25272-5

- Seidman, David, and Cleveland, Paul, The Essential Wilderness Navigator, Ragged Mountain Press (2001), ISBN 0-07-136110-3

- Taylor, E.G.R. (1951). "The South-Pointing Needle". Imago Mundi. 8: 1–7. doi:10.1080/03085695108591973.

- Williams, J.E.D. (1992) From Sails to Satellites: the origin and development of navigational science, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-856387-6

- Wright, Monte Duane (1972) Most Probable Position: A History of Aerial Navigation to 1941, The University Press of Kansas, LCCN 72-79318

- Zhou, Daguan (2007) The customs of Cambodia, translated into English from the French version by Paul Pelliot of Zhou's Chinese original by J. Gilman d'Arcy Paul, Phnom Penh : Indochina Books, prev publ. by Bangkok : Siam Society (1993), ISBN 974-8298-25-6