Hot cross bun

Homemade hot cross buns | |

| Type | Spiced bun |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Main ingredients | currants or raisins |

|

| |

A hot cross bun is a spiced sweet bun made with currants or raisins, marked with a cross on the top, and traditionally eaten on Good Friday in Australia, British Isles, Canada, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa and some parts of America. The buns mark the end of Lent and different parts of the hot cross bun have a certain meaning, including the cross representing the crucifixion of Jesus, and the spices inside signifying the spices used to embalm him at his burial.[1][2] They are now available all year round in some places.[3] Hot cross buns may go on sale in Australia and New Zealand as early as New Year's Day[4] or after Christmas.[5]

History

In many historically Christian countries, plain buns made without dairy products (forbidden in Lent until Palm Sunday) are traditionally eaten hot or toasted during Lent, beginning with the evening of Shrove Tuesday (the evening before Ash Wednesday) to midday Good Friday.

The ancient Greeks may have marked cakes with a cross.[6]

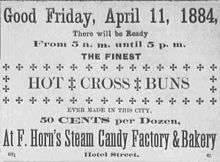

In the time of Elizabeth I of England (1592), the London Clerk of Markets issued a decree forbidding the sale of hot cross buns and other spiced breads, except at burials, on Good Friday, or at Christmas. The punishment for transgressing the decree was forfeiture of all the forbidden product to the poor. As a result of this decree, hot cross buns at the time were primarily made in home kitchens. Further attempts to suppress the sale of these items took place during the reign of James I of England/James VI of Scotland (1603–1625).[7] The first definite record of hot cross buns comes from a London street cry: "Good Friday comes this month, the old woman runs. With one or two a penny hot cross buns", which appeared in Poor Robin's Almanack for 1733.[8] Food historian Ivan Day states, "The buns were made in London during the 18th century. But when you start looking for records or recipes earlier than that, you hit nothing."[3]

Traditions

English folklore includes many superstitions surrounding hot cross buns. One of them says that buns baked and served on Good Friday will not spoil or grow mouldy during the subsequent year. Another encourages keeping such a bun for medicinal purposes. A piece of it given to someone ill is said to help them recover.[9] If taken on a sea voyage, hot cross buns are said to protect against shipwreck. If hung in the kitchen, they are said to protect against fires and ensure that all breads turn out perfectly. The hanging bun is replaced each year.[9]

Other versions

In the United Kingdom, the major supermarkets produce variations on the traditional recipe such as toffee, orange-cranberry, and apple-cinnamon.[3]

In Australia and New Zealand, a chocolate version of the bun has become popular; coffee-flavoured buns are also sold in some Australian bakeries.[10] They generally contain the same mixture of spices, but chocolate chips are used instead of currants. There are also fruit-less, sticky date and caramel versions, as well as mini versions of the chocolate and traditional bun.[11]

The not cross bun is a variation on the hot cross bun. It uses the same ingredients but instead of having a "cross" on top, it is has a smiley face in reference to it being "not cross" or "angry". The not cross bun was first sold commercially in 2014 by an Australian bakery, Ferguson Plarre Bakehouses, in response to supermarkets selling hot cross buns as early as Boxing Day (26 December).[12]

In the Czech Republic, mazanec is a similar cake or sweet bread eaten at Easter. It often has a cross marked on top.[13]

In the Bremen area in northern Germany a "Hedwig" (lower Saxon: heet week) was an ancient Shrove Tuesday meal. On Shrove Tuesday the top of a Hedwig was cut off and the Hedwig was filled with a tablespoon of hot butter and cinnamon-powder. The top was put back again and the Hedwig was served in a soup plate filled with hot milk or cream. At last a tablespoon of cinnamon-sugar mulled over the Hedwig, then eaten with a tablespoon. Today a Hedwig is the sweet part of a Sunday breakfast in northern Germany.

In Frisia, the northern part of the Netherlands, there are "Hite wigge". They are very close to the original hot cross bun and Bremen's Hedwig.

The cross

The traditional method for making the cross on top of the bun is to use shortcrust pastry;[14][15] however, more recently recipes have recommended a paste consisting of flour and water.[16]

See also

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Cookbook:Hot Cross Bun |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hot cross buns. |

- Bath bun

- Fruit bun

- Sally Lunn bun

- List of British breads

- List of buns

- List of foods with religious symbolism

References

- ↑ Turner, Ina; Taylor, Ina (1999). Christianity. Nelson Thornes. p. 50. ISBN 9780748740871.

To mark the end of the Lent fast Christians eat hot cross buns. These have a special meaning. The cross in the middle shows how Jesus died. Spices inside remind Christians of the spices put on the body of Jesus. Sweet fruits in the bun show that Christians no longer have to eat plain foods.

- ↑ Fakes, Dennis R. (1 January 1994). Exploring Our Lutheran Liturgy. CSS Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 9781556735967.

Since people often gave up meat during Lent, bread became one of the staples of Lent. Bakers even began making dough pretzels--a knotted length of dough that represented a Chrsitian praying, with arms crossed and hands placed on opposite shoulders. Hot cross buns are popular during Lent. The cross of course reminds the eater of Christ's cross.

- 1 2 3 Rohrer, Finlo (1 April 2010). "BBC - How did hot cross buns become two a penny?". BBC News. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Hot Cross Buns on sale already". au.tv.yahoo.com. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ↑ Dodd, Kate (3 January 2014). "Easter's come early: hot cross buns already on shelves". The Toowoomba Chronicle. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Who Were The First To Cry "Hot Cross Buns?"". The New York Times. 31 March 1912. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ David, Elizabeth (1980). "Yeast Buns and Small Tea Cakes". English Bread and Yeast Cookery. New York: The Viking Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN 0670296538.

- ↑ Charles Hindley (2011). "A History of the Cries of London: Ancient and Modern". p. 218. Cambridge University Press,

- 1 2 "Hot Cross Buns". Practically Edible: The Web's Biggest Food Encyclopedia. Practically Edible. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "Easter Baking: Hot Cross Buns". jeanniebayb.livejournal.com. 24 March 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "Yummy Hot Cross Buns". Woolworths (Australia). Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Baker launches war on supermarkets' early hot cross bun sales". Good Food. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Easter in Czech Republic". iloveindia.com. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ↑ Berry, Mary (1996). Mary Berry's Complete Cookbook (First edition (2nd reprint) ed.). Godalming, Surrey: Dorling Kindersley. p. 386. ISBN 1858335671.

- ↑ Smith, Delia (1986). Delia Smith's Cookery Course (First edition (8th reprint) ed.). London: British Broadcasting Corporation. p. 62. ISBN 0563162619.

- ↑ "The Great British Bake-off: Paul Holywood's Hot Cross Bun", Easy Cook (magazine) (60), p. 38, April 2013