1982 Pacific hurricane season

| |

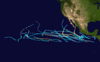

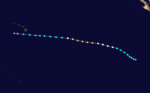

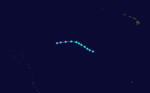

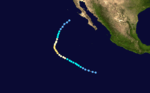

| Season summary map |

| First system formed |

May 20, 1982 |

| Last system dissipated |

November 25, 1982 |

| Strongest storm1 |

Olivia – 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Total depressions |

30 |

| Total storms |

23 |

| Hurricanes |

12 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) |

5 |

| Total fatalities |

2,005 |

| Total damage |

$2.4 billion (1982 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure |

Pacific hurricane seasons

1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984 |

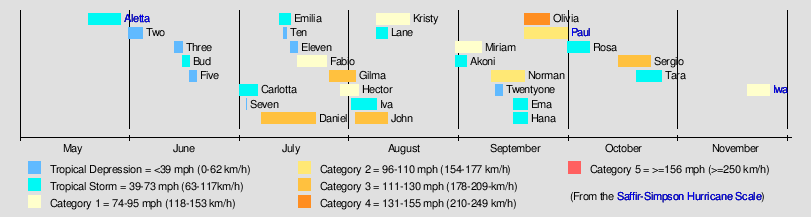

The 1982 Pacific hurricane season is the fifth most active Pacific hurricane season. It was at that time the most active season in the basin it was later surpassed by the 1992 season. It officially started June 1, 1982 in the eastern Pacific, and June 1, 1982 in the central Pacific, and lasted until October 31, 1982 in the central Pacific and until November 15, 1982 in the Eastern Pacific.[1] These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. At that time, the season was considered as the most active season within the basin, however the 1992 season surpassed these numbers.

The 1982 season was an eventful one. Hurricane Paul killed over 1,000 people before it was named. Hurricanes Daniel and Gilma both briefly threatened Hawaii, while Hurricane Iwa caused heavy damage to Kauai and Niihau. The remnants of Hurricane Olivia brought heavy rain to a wide swath of the western United States.

Seasonal summary

This season had twenty three tropical storms, twelve hurricanes, and five major hurricanes. Three tropical storms and one hurricane— a record number of named storms— formed in the central Pacific. This was largely due to the strong 1982–83 El Niño event, which was present during the season.[2] However, this was surpassed in the 2015 Pacific hurricane season with eight storms.

This is the first year that named storms forming between the dateline and 140°W were given names from the Hawaiian language. Previous to this year, names and numbers from the western Pacific's typhoon list were used.

After this year that it was decided to use six-year lists in the eastern Pacific, instead of four-year ones. This is the reason that this season's list is the same as the 1978 season's list.

Storms

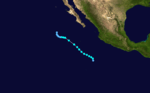

Tropical Storm Aletta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

May 20 – May 29 |

| Peak intensity |

65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) |

The origins of Aletta are from a tropical disturbance that was first noted on May 18 about 500 mi (800 km) south-southwest of Acapulco. On May 20, the disturbance was upgraded into a tropical depression. Moving northwest, the depression became Tropical Storm Aletta 36 hours later. The system re-curved towards the northeast due to strong upper-level westerlies, reaching its peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h) on May 23.[2] Shortly after its peak, Tropical Storm Aletta began to weaken. However, the system briefly leveled off in intensity for 30 hours before resuming a weakening trend.[3] On May 25, Aletta slowed and moved in a large clockwise loop until May 28. Shortly thereafter, Tropical Storm Aletta was downgraded into a depression. Tropical Depression Aletta dissipated on May 29 roughly 180 mi (290 km/h) southwest of Acapulco.[2]

The outer rainbands of Tropical Storm Aletta produced torrential rains and high winds over Central America for several days,[4][5][6] with a peak of 57.32 in (1,456 mm) in Chinandega.[7] Ninety percent of the banana crop and 60 percent of the corn crop was completely destroyed.[4] Throughout the country, 108 people were killed,[6] Roughly 20,000 people were homeless[4] and total damage was estimated at $365 million (1982 USD);[8] damage to highways, factories, and farms alone exceeded $100 million.[6] In one village, the storm left 270 missing and only 29 survivors.[9] The capital city of Leon was hardest hit by Aletta,[10] which was considered the worst disaster in the country in three years.[6]

Across Honduras, 200 people were killed[4] and 5,000 people were without food or water 13 communities.[11] A total of 80,000 people were homeless.[5] Total damage was placed at $101 million (1982 USD).[8] Following the storm, soldiers quickly sent food and medical to at least 50 communities in both countries.[12] To prevent an epidemic of diseases such as typhoid fever, the Health Ministry started a program to give out vaccines.[6] In addition, the U.S. Embassy in Honduras attempted to outline a fact-fining mission to assess the damage and provide relief.[13]

Tropical Depression Two-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

May 31 – June 4 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

This system originated as a low in the western Caribbean Sea on the morning of May 27. The next day it moved southwest into Guatemala with significant thunderstorm activity, emerging into the Gulf of Tehuantepec around noon on May 29. By May 31, it was organized enough to be considered a tropical depression. Slowly weakening on June 1 as it remained quasi-stationary, the system dissipated in the Gulf of Tehuantepec on June 4.[2]

Tropical Depression Three-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

June 13 – June 15 |

| Peak intensity |

30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) |

This cyclone formed well to the west-southwest of Mexico on June 12. The depression slowly recurved due to an upper level low located well to its north-northwest. By June 15, vertical wind shear had taken its toll and the system dissipated about 300 mi (500 km) north of where it formed.[2]

Tropical Storm Bud

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

June 15 – June 17 |

| Peak intensity |

50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) |

On June 15, this cyclone formed about 460 mi (740 km) southwest of Acapulco. Drifting west-northwest, it quickly strengthened into a tropical storm. Maximum sustained winds peaked near 50 mph (80 km/h) late on June 15. Turning south of due west, vertical wind shear weakened Bud, with the cyclone dissipating by the morning of June 17 about 23 mi (370 km) north-northwest of Clipperton Island.[2]

Tropical Depression Five-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

June 17 – June 19 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

Late on June 16, deep convection organized in the Gulf of Tehuantepec into a tropical depression. Transcribing a small clockwise loop, the system moved west-northwest. Interaction with Mexico likely played a role in its weakening as water temperatures under the system were never below 82 °F (28 °C). The system dissipated about 90 mi (150 km) south of Puerto Ángel by the morning of June 19.[2]

Tropical Storm Carlotta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 1 – July 6 |

| Peak intensity |

60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical wave crossed Central America on June 26, creating an area of thunderstorms just inside the tropical eastern Pacific that morning. Cyclonic turning was evident by the night of June 30 while located roughly 350 mi (550 km) south of Manzanillo as the system continued westward. Slowly turning northwest, the system was upgraded to a tropical depression early on July 1 and a tropical storm by nightfall. Maximum sustained winds increased to 60 mph (97 km/h) by noon July 3. Increasingly southwest flow aloft turned Carlotta more northward into cooler waters, causing the cyclone to regain tropical depression status on the evening of July 4, ultimately dissipating southwest of Cabo San Lucas the next evening.[2]

Tropical Depression Seven-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 3 – July 3 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

The system formed between Tropical Storm Carlotta and the Hawaiian Islands on the evening of July 2. Slowly recurving north and northeast, the system moved into cooler waters and dissipated about 100 mi (160 km) north of where it formed by the afternoon of July 3.[2]

Hurricane Daniel

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 7 – July 22 |

| Peak intensity |

115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression Eight-E formed south of Mexico on July 7. Moving west-northwest, the cyclone slowly strengthened into a tropical storm around noon on July 8 before becoming a hurricane late in the afternoon of July 9. Daniel reached its maximum intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) early in the morning of July 11 a few hundred miles southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. As the storm moved westward, it slowly weakened. Daniel regained tropical storm status during the night of July 14, entering the Central Pacific Basin as a weakening tropical storm on the morning of July 16. Daniel retained tropical storm intensity for the next few days before weakening into a tropical depression about 280 mi (450 km) south southwest of the Big Island of Hawaii, being sheared by the same upper trough that caused Emilia's dissipation a few days earlier. Daniel turned northward, and on July 22, dissipated in the Alenuihaha Channel between Maui and the Big Island of Hawaii.[14]

Tropical Storm Emilia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 12 – July 15 |

| Peak intensity |

65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression Nine-E developed near 10.0° N 136.5° W on the morning of July 12. Intensifying, the cyclone became a tropical storm later that day. Emilia moved westward around 13 mph (21 km/h) and entered the Central Pacific Basin on the night of July 12. Over the next day, the storm moved west-northwest, reaching maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). An upper trough to the west weakened Emilia rapidly due to vertical wind shear, and the cyclone weakened to tropical depression status early on the morning of July 15. Dissipation of the tropical depression was noted by afternoon.[14]

Tropical Depression Ten-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 13 – July 14 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

To the east of Daniel, a tropical depression formed on the evening of July 13 a few hundred miles west-southwest of Manzanillo. The system moved westward and weakened thereafter, dissipating about 200 mi (320 km) west of where it had formed by the afternoon of July 14.[2]

Tropical Depression Eleven-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 15 – July 17 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical disturbance was spotted about 650 mi (930 km) southwest of Acapulco on July 12. By the evening of July 15, cyclonic turning was evident and the system was upgraded to a tropical depression. Moving unsteadily to the west-northwest, the system weakened, dissipating a few hundred miles west-northwest of where it had formed.[2]

Hurricane Fabio

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 17 – July 25 |

| Peak intensity |

80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

The cyclone developed as a tropical depression southeast of Manzanillo on July 17. Over the next couple of days, it strengthened rapidly into a hurricane as it moved northwest, peaking in intensity with 75 mph (121 km/h) winds. Gradual weakening occurred as Fabio turned westward along the 19th parallel north into cooler waters, eventually dissipating late on July 24.[2]

Hurricane Gilma

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 26 – August 2 |

| Peak intensity |

125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression Thirteen-E formed near 9.5°N 117°30'W and moved slightly north of west. Tropical storm status was attained near noon on July 26, and the cyclone crossed the threshold of hurricane strength late on the night of July 27. By noon on July 29, Gilma reached it maximum intensity of 125 mph (200 km/h) well to the east-southeast of Hawaii. The cyclone weakened and sped up its motion to the west-northwest, crossing into the Central Pacific Basin as a category one hurricane very early on July 30. Gilma was downgraded to a tropical storm late in the morning of July 30, and a tropical depression early on the morning of August 1 as the circulation passed 50 mi (80 km) south of South Point. The cyclone dissipated late on August 1 as it passed 200 mi (300 km) south of Kauai.[14]

Hurricane Hector

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 29 – August 3 |

| Peak intensity |

75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) |

On July 23, a tropical wave moved off the Colombian coast. The related convection moved westward at over 20 mph (32 km/h). By the evening of July 27, the system slowed its forward motion. The next evening, a tropical depression organized within the thunderstorm activity well to the south of Baja California. Strengthening continued, as Hector became a tropical storm on the morning of July 29 and a hurricane by noon on July 30. A combination of vertical wind shear and cooler waters ahead of the cyclone led to its weakening trend, which hastened on August 1. It weakened to a tropical storm on the morning of August 2 and to a depression soon thereafter while located midway between the Hawaiian Islands and southern Baja California.[2]

Tropical Storm Iva

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 1 – August 8 |

| Peak intensity |

40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical disturbance was discovered 300 mi (460 km) south of Acapulco on July 31. Moving west-northwest, it achieved tropical depression status that night and tropical storm status on August 2 while 800 mi (1,340 km) west-southwest of Acapulco. Northeasterly upper level shear appears to have been Iva's nemesis, as the system weakened back into a tropical depression by the afternoon of August 3 as it turned west-southwest. The depression maintained strength for another several days before dissipating well east-southwest of Hilo, Hawaii on the morning of August 8.[2]

Hurricane John

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 2 – August 11 |

| Peak intensity |

115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression Sixteen-E formed on August 3 in the East Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico. The system intensified into a tropical storm by noon August 4, and a hurricane on the morning of August 5. John reached its peak intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) as it moved into the Central Pacific Basin on August 6. Weakening commenced on August 7 due to westerly vertical wind shear caused by the semi-permanent mid-oceanic upper trough, and John weakened to a tropical storm on the night of August 8. It passed by as a tropical depression about 180 mi (290 km) south of the Island of Hawaii, and dissipated late on August 10 to the southwest of Hawaii.[14]

Hurricane Kristy

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 8 – August 17 |

| Peak intensity |

90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Seventeen-E formed by noon on August 8 in the East Pacific. The low moved west, intensified, and became Tropical Storm Kristy by midnight, and a hurricane by midnight on the night of August 9. Weakening as it entered the Central Pacific, Kristy regained tropical storm status late on August 10 while moving south of due west at a rapid 30 mph (48 km/h). As it slowed down and turned northwest, Kristy began to restrengthen. Hurricane intensity was reached again on the evening of August 13. By noon on August 14, the cyclone passed 250 mi (400 km) south of South Point, Hawaii. Westerly winds aloft slowed Kristy's forward motion down additionally, and Kristy weakened back into a tropical storm on August 15. Turning more to the west with the low level wind flow, the cyclone was downgraded to a tropical depression by noon on August 16 and dissipated that night southwest of Hawaii.[14]

Tropical Storm Lane

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 8 – August 15 |

| Peak intensity |

65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) |

The originating disturbance of this system emerged off San José, Costa Rica on August 4 and slowly consolidated. By the afternoon of August 8, Tropical Depression Eighteen-E developed well south of Cabo San Lucas. The next morning it had continued strengthening into a tropical storm. Maximum sustained winds reached 60 mph (97 km/h) as it continued moving west-northwest. Vertical wind shear reached Lane on August 10, which led to weakening. It weakened to a tropical depression late on August 11, but sporadic thunderstorm blowups near the center kept the system alive for another few days. Dissipation occurred on the evening of August 14 as it crossed the 140th meridian west.[14]

Hurricane Miriam

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 30 – September 6 |

| Peak intensity |

85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression Nineteen-E formed on August 29 a couple hundred miles southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. The depression moved west-northwestward, intensifying into a tropical storm by noon on August 30 and a hurricane by noon on August 31. Peak intensity of 90 mph (145 km/h) was attained during the early morning of September 1. For the next couple of days, Miriam remained unchanged in strength. By late on September 3, a weakening trend was realized as it passed into the Central Pacific by the afternoon of September 4. Shearing apart soon afterwards, the low moved northwest and weakened into a tropical depression well to the east of Hawaii on the morning of September 5. It drifted north, and became a nontropical low by September 6. The cyclone was last noted near 30°N 149°W, continuing its northward trek.[14]

Tropical Storm Akoni

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 30 – September 2 |

| Peak intensity |

50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) |

Tropical Depression One-C formed along the eastern end of the West Pacific monsoon trough on August 30 about 700 mi (1120 km) east of the International Dateline, well to the west-southwest of Hawaii. Moving slowly westward, the system intensified rapidly into a tropical storm by noon and was named Akoni.[14] The name "Akoni" is short for Anakoni, which is Hawaiian for "Anthony".[15] Maximum sustained winds increased to 60 mph (97 km/h) late on August 31 as Akoni moved near the ship Nana Lolo a few hundred miles east of the International Dateline. An upper trough to the northwest set Akoni on a weakening curve, and the cyclone diminished to a tropical depression on the evening of September 1 as it moved with the low level flow. The weakening depression passed the International Dateline into the western Pacific on the morning of September 2.[14] Akoni was the first storm to receive a name from the modern Central Pacific tropical cyclone naming list.[16]

Hurricane Norman

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 9 – September 18 |

| Peak intensity |

105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

Northeasterly shear slowed the development of the initial tropical depression which formed into Norman. Strengthening began in earnest on September 11, and the cyclone became a tropical storm, and then a hurricane by early on September 13. Maximum sustained winds reached nearly 95 mph (153 km/h) by September 15. A mid-latitude trough dug in from the north, weakening the ridge north of Norman and leading to a northward motion. Increased vertical wind shear and cooler waters weakened the hurricane, with dissipation occurring just west of Baja California on September 18. On September 17 and 18, moisture from Norman brought scattered rain to California and Arizona.[17]

Tropical Depression Twenty-One-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 10 – September 12 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical depression formed well east-southeast of Hawaii late on September 10. Moving over cooler waters soon after formation, the depression dissipated by the next evening near 14°N 134°W.[2]

Tropical Storm Ema

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 15 – September 19 |

| Peak intensity |

45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) |

An area of convection formed near 15°N 140°W and by 15 September, a tropical depression had formed within the thunderstorm activity. Strengthening as it moved slowly north-northeast, the cyclone became a tropical storm late that day. Ema became stationary between the morning of September 16 and September 17 before resuming its north-northeast heading. Its peak intensity was 45 mph (72 km/h). Upper level shear weakened the system into a tropical depression by noon on September 18. As it crossed the 140th meridian west back into the eastern Pacific near the 20th parallel north, the depression dissipated.[14]

Tropical Storm Hana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 15 – September 19 |

| Peak intensity |

45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) |

An area of thunderstorms stewed south of the Hawaiian Islands for several days. By September 15, it had organized into Tropical Depression Three-C, and quickly became a tropical storm that afternoon. The cyclone moved north-northwest for a day before slowing to a crawl for the next day. The cyclone turned southwest and weakened into a tropical depression due to vertical wind shear. It dissipated southwest of Hawaii near 13°N 162°W late on September 18.[2]

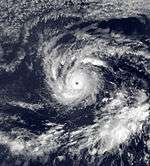

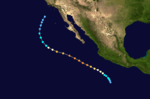

Hurricane Olivia

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 18 – September 25 |

| Peak intensity |

145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) |

Ship reports indicated that a tropical depression had formed about 400 mi (640 km) south-southwest of Acapulco around noon on September 18. The system drifted north-northwest, developing into a tropical storm that night. About 24 hours later, Olivia became a hurricane. Rapid intensification continued, and Olivia reached its peak intensity of 130 mph (210 km/h) winds around noon September 21, becoming the strongest storm of the season. The next day, waters under the tropical cyclone began to cool as the hurricane gained increasing latitude offshore Mexico. By noon on September 23, the cyclone had weakened into a tropical storm west of Baja California. Strong southwest flow to its north spread precipitation through the western United States into southwest Canada. The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression about 500 mi (800 km) southwest of San Diego and the surface low was last seen dissipating on September 25 about 250 mi (400 km) west-southwest of San Diego.

The heavy rain in California wiped out half of the raisin crop, a quarter of the wine crop, and a tenth of the tomato crop. Olivia's remnants brought rain totals of over 7 inches (177 mm) to California and northern Utah as they interacted with a strong upper level system and the local topography.[18] The precipitation from this storm largely contributed to the record monthly precipitation in Salt Lake City, Utah of 7.04 in (179 mm). These rains resulted in widespread losses, mainly from agriculture, amounting to $325 million (1982 USD).[2]

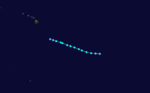

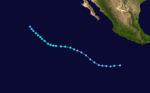

Hurricane Paul

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 18 – September 30 |

| Peak intensity |

110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) |

The precursor disturbance to Paul originated from an area of low barometric pressure and disorganized thunderstorms, which was first noted near the Pacific coast of Nicaragua on September 15. Five days later, the EPHC classified it as Tropical Depression Twenty-Two. The depression turned northward and then moved inland near the El Salvador–Guatemala border, and dissipated overland.[2] The remains of the depression retraced westward back over the open waters of the Pacific, briefly regenerating into a tropical depression. The depression again degenerated into an open trough on September 22. Two days later, Paul regenerated for the third time. It gradually organized into a tropical storm at 0000 UTC September 25. Two days later, Paul became a hurricane and turned north.[2] As the storm neared Baja California Sur, it reached Category 2 intensity.[3] On September 29, the hurricane crossed Baja California Sur at peak intensity. After weakening slightly inland, Paul made its final landfall near Los Mochis[2] before rapidly dissipating overland.[3]

The tropical depression that later became Paul produced the worst natural disaster in El Salvador since 1965.[2] A total of 761 people were killed[19] 312 of which occurred in San Salvador,[20] which also sustained the worst damage.[20][21][22] About 25,000–30,000 people were left homeless.[2] Much of San Salvador was submerged by flood waters of up to 8 ft (2.4 m) high, and even after their recession hundreds of homes remained buried under trees, debris, and 10 ft (3.0 m) of mud.[2][20] In all, property damage from the storm amounted to $100 million (1982 US$) in the country;[20] economic losses were estimated at $280 million (1982 USD).[23] Crop damage was worth $250 million.[24]

In Guatemala, widespread catastrophic floods claimed 615 lives and left 668 others missing. More than 10,000 people were left homeless as[25] The 200 communities were isolated from surrounding areas.[26] Overall, economic losses of $100 million (1982 USD) were reported in the country.[27] In Nicaragua, Paul killed 71 people and caused $356 million (1982 USD) in economic losses.[28] Throughout southern Mexico, floods from the precursor depression to Paul killed another 225 people.[29] Prior to landfall in the state of Baja California Sur, 50,000 people were evacuated.[30] Furthermore, wind gusts estimated at 120 mph (195 km/h) swept through San José del Cabo, causing property damage and subsequently leaving 9,000 homeless.[2] Despite extensive damage, no deaths were reported in the Baja California Peninsula wake of Paul.[30] In northern Mexico, the greatest damage occurred 70 miles (110 km) south of Los Mochis in the city of Guamuchil;[2] a total of 24 people were killed by the storm statewide, although it produced beneficial rains over the region.[31] Agricultural damage was severe in the state of Sinaloa, with up to 40 percent of the soybean crop destroyed. In all, the state's corn production was down by 26 percent from the previous year. Total storm damage in Mexico amounted to $4.5 billion (1982 MXN; $70 million USD).[2] The remnants of Paul moved into the United States, producing heavy rainfall in southern New Mexico and extreme West Texas. Inclement weather was observed as far inland as the Great Plains.[32]

Tropical Storm Rosa

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 30 – October 6 |

| Peak intensity |

50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) |

A well-organized tropical depression formed in the Gulf of Tehuantepec on September 30. Moving slowly northwest, the system became a tropical storm, reaching maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on the afternoon of October 2. The system slowly weakened as it moved northwest, and Rosa brushed the Pacific coast of Mexico as a dissipating depression.[2]

Hurricane Sergio

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

October 14 – October 23 |

| Peak intensity |

125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical disturbance was noted southwest of Costa Rica on October 12. Moving west-northwest, the system organized into a tropical depression as it crossed the 91st meridian west late on October 13 and became a tropical storm by October 14 as it entered the Gulf of Tehuantepec. It strengthened into a hurricane late that day as it passed 95°W. By the afternoon of October 17, Sergio was packing sustained winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). Cooler water was reached soon afterwards, and weakening commenced. While slowly moving west, Sergio weakened to a tropical storm by the afternoon of October 21 and to a tropical depression late on October 22. The system dissipated near 19°N 133°W on the afternoon of October 23.[2]

Tropical Storm Tara

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

October 19 – October 26 |

| Peak intensity |

50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical disturbance emerged off the coast of Central America. Cyclonic turning was noted on the afternoon of October 19, and a tropical depression formed 350 mi (560 km) south of Acapulco. Staggering west-northwestward, the cyclone became a tropical storm by the morning of the October 22. Maximum sustained winds increased to 50 mph (80 km/h) late on October 24. As it moved over cooler waters on October 25, the system weakened to a tropical depression that afternoon, dissipating that night near 21°N 130°W.[2]

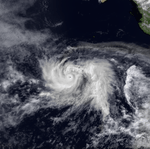

Hurricane Iwa

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

November 19 – November 25 |

| Peak intensity |

90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) |

A late-season trough of low pressure developed into a tropical depression and was subsequently upgraded into Tropical Storm Iwa. At first, the After turning to the northeast, Iwa began to slowly intensify, and on November 23, Iwa strengthened into a hurricane.[14][33] Iwa reached peak winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) late on November 23. Accelerating, Iwa passed just north of the island of Kauai on November 24. After passing the island group, Iwa rapidly deteriorated; late on November 24, the hurricane degenerated into a tropical storm. On November 25, Iwa became an extratropical cyclone.[33]

Due to the hurricane's rapid motion,[33] storm surge extended 900 feet (275 m) inland.[34] A total of 5,800 people were evacuated in Kauai.[33] In addition, 44 of the 45 boats at Port Allen sunk.[35] The worst of the damage from the hurricane occurred in Poipu and in areas where there was no protective barrier reef offshore.[33] High winds from Hurricane Iwa briefly left Kauai without power[36] and destroyed most papaya and banyan trees.[37] The hurricane destroyed or damaged 3,890 homes on the island.[38] Rough seas killed a person and left four others injured in Pearl Harbor.[14][39] In Oahu, damage was heaviest on the southwest side of the island.[33] The passage of the hurricane damaged at least 6,391 homes and 21 hotels;[40] 418 buildings, including 30 businesses, were destroyed on Oahu.[38] In Niihau, 20 homes were destroyed and 160 were damaged.[38]

Throughout the Hawaiian island group, 20 people were treated for injuries.[39] An estimated 500 people throughout Hawaii were left homeless due to the hurricane.[39] At the time, Hurricane Iwa was the costliest storm to hit the state,[34] with damage totaling $312 million (1982 USD, $766 million 2016 USD).[41] Three days after Hurricane Iwa passed the state, Governor George Ariyoshi declared the islands of Kauai and Niihau as disaster areas[42] with President Ronald Reagan following suit on November 28, declaring Kauai, Niihau, and Oahu as disaster areas.[40] Furthermore, two people died in a traffic accident due to malfunctioning traffic lights.[43] Ten years following the storm, Hurricane Iniki struck the same area.[44]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the eastern Pacific in 1982. No Eastern Pacific names were retired, so it was used again in the 1988 season. This is the same list used in the 1978 season, except for Fabio, which replaced Fico. A storm was named Fabio for the first time in 1982. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

- Aletta

- Bud

- Carlotta

- Daniel

- Emilia

- Fabio

- Gilma

|

- Hector

- Iva

- John

- Kristy

- Lane

- Miriam

- Norman

|

- Olivia

- Paul

- Rosa

- Sergio

- Tara

-

Vicente (unused)

-

Willa (unused)

|

Four names from the Central Pacific list were used – Akoni, Ema, Hana, and Iwa. This was the first usage for all of these names.

With four names being used, this season held the record for most named storms forming in the Central Pacific, until it was surpassed by the 2015 season.

Retirement

One name was retired from the Central Pacific list after the 1982 season, Iwa. It was replaced with Io (which was later changed to Iona before its usage). Iwa is one of only four Central Pacific names to have been retired.

See also

References

- ↑ "Hurricane Season Quietest in 50 years". The Palm Beach Post. November 29, 1982. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Gunther, Emil B.; R.L. Cross; R. A. Wagoner (May 1983). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1982". Monthly Weather Review. 111 (5): 1080–1102. Bibcode:1983MWRv..111.1080G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1080:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2015". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- 1 2 3 4 "Canada Aids Victims". The Leader-Post. June 10, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- 1 2 Associated Press (May 29, 1982). "Tropical Storm Leaves 80,000 Homeless In Honduras". Observer-Reporter. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nicaragua seeks aid as flood victims kill 108". The Montreal Gazette. May 28, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ↑ Wilfried Strauch (November 2004). "Evaluación de las Amenazas Geológicas e Hidrometeorológicas para Sitios de Urbanización" (PDF). Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER). p. 11. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- 1 2 "Tropical Storm Aletta". Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Mudslides hit Nicaragua". The Summer Daily Item. May 31, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Nicaragua declares flood disaster". The Telegraph-Herald. May 26, 1982. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Killer tropical storm continues". Tri City Herald. May 23, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Nicaragua Appeals For Aid As Tropical Storm Kills 17". Observer-Reporter. Associated Press. May 28, 1982. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. eyes on Nicaragua flood aid". The Telegraph-Herald. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1982 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 1982. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Behind the Name: Hawaiian names". Behind the Name. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Central North Pacific names". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/enso/tropstorm.nws

- ↑ Remains of Olivia - September 23–28, 1982

- ↑ "More Flood Victims found". The Spokesman-Review. September 28, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "El Salvador Death Toll hits 565 as more bodies found". September 22, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Salvador Flood total 565". The Courier. September 23, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Death toll expected to hit 500 in Salvador flood disaster". The Deseret News. September 21, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "El Salvador - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ↑ "5 day toll in El Salvador, 630 killed, crops, destroyed". Anchorage Daily Times. September 23, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "More flood victims found". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. September 28, 1982. p. 12. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Death from Salvadoran flood exceeds 1,200". Anchorage Daily News. September 24, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Guatemala - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Nicaragua - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Mexico - Disaster Statistics". Prevention Web. 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- 1 2 "Hurricane hits Baja California". L.A. Times. October 1, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ↑ "24 killed from hurricane". The Hour. October 1, 1982. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Local National International". Sarsota Herald-Tribune. September 1, 1982. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mariners Weather Log: Spring 1983 (Report). Mariners Weather Log. Spring 1983.

- 1 2 Summary of Significant Floods, 1982 (Report). United States Geological Survey. 2005. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Anthony Sommer (2002). "Lessons Learned from Iniki leave officials better prepared for any future disasters". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Iwa Hits Hawaiian Island of Kauai". The New York Times. United Press International. November 24, 1982.

- ↑ "Kauai Recovering from Punishment Sustained from Hurricane in November". United Press International. December 19, 1983.

- 1 2 3 "Power Still Out in Parts of Kauai". The New York Times. United Press International. November 30, 1982.

- 1 2 3 "One Dead in Hawaii Storm; Damage to 3 Islands Severe". The New York Times. United Press International. November 25, 1982.

- 1 2 "Hawaii Hurricane Path Declared Disaster Area". The New York Times. United Press International. November 28, 1982.

- ↑ The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2006 (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (Report). 2007. p. 26. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ United Press International (November 26, 1982). "Hawaii Storm Cost Near $200 Million". The New York Times.

- ↑ Michael Tsai (July 2, 2006). "Hurricane Iwa". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Charles Fletcher; Eric Grossman; Bruce Richmond (2000). Hawaii Hazard Mitigation Forum (Report). Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

External links

|

|---|

|

| |

|

-

Book Book

-

Category Category

-

Portal Portal

-

WikiProject WikiProject

-

Commons Commons

|